Полная версия:

On Beulah Height

REGINALD HILL

ON BEULAH HEIGHT

A Dalziel and Pascoe novel

Copyright

Harper an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Copyright © Reginald Hill 1998

Reginald Hill asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction.

The names, characters and incidents portrayed

in it are the work of the author’s imagination.

Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead,

events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780006490005

Ebook Edition © JULY 2015 ISBN: 9780007374014

Version: 2015-06-19

Dedication

For Allan

a wandering minstrel, he!

Epigraph

Then I saw that there was a way to hell, even from the gates of heaven.

JOHN BUNYAN: The Pilgrim’s Progress

O where is tinye Hew?

And where is little Lenne?

And where is bonny Lu?

And Menie of the Glenne?

And where’s the place of rest –

The ever changing hame?

Is it the gowan’s breast,

Or ’neath the bells of faem?

Ay, lu, lan, dil y’u

ANON: The Gloamyne Buchte

Wir holen sie ein auf jenen Höh’n

Im Sonnenschein.

Der Tag ist schön auf jenen Höh’n

FRIEDRICH RÜCKERT:

Kindertotenlieder IV

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Day One: A Happy Rural Seat of Various View

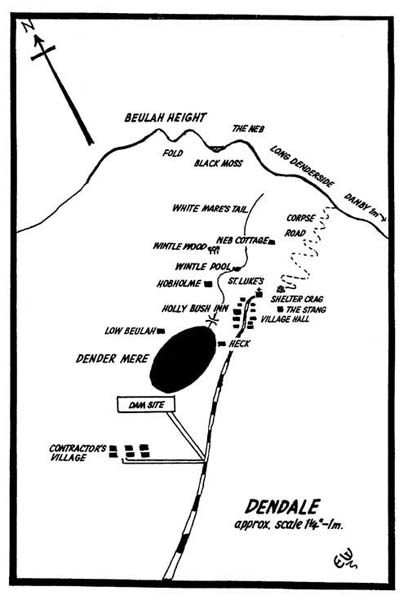

MAP

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

Day Two: Nina and the Nix

EDITOR’S FOREWORD

NINA AND THE NIX

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

Day Three: The Drowning of Dendale

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

Day Four: Songs for Dead Children

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

Keep Reading

About the Author

By Reginald Hill

About the Publisher

MAP

ONE

BETSY ALLGOOD [PA/WW/4.6.88]

TRANSCRIPT 1

No 2 of 2 copies

The day they drowned Dendale I were seven years old.

I’d been three when government said they could do it, and four when Enquiry came out in favour of Water Board, so I remember nowt of that.

I do remember something that can’t have been long after, but. I remember climbing up ladder to our barn loft and my dad catching me there.

‘What’re you doing up here?’ he said. ‘Tha knows it’s no place for thee.’

I said I were looking for Bonnie, which were a mistake. Dad had no time for animals that didn’t earn their keep. Cat’s job was keeping rats and mice down, and all that Bonnie ever caught was a few spiders.

‘Yon useless object should’ve been drowned with rest,’ he said. ‘You come up here again after it and I’ll get shut of it, nine lives or not.’

Before I could start mizzling, sound of a machine starting up came through the morning air, not a farm machine but something a lot bigger down at Dale End. I knew there were men working down there, but I didn’t understand yet what they were doing.

Dad went to the open hay door and looked out. Low Beulah, our farm, were built on far side of Dender Mere from the village and from up in our loft you got a good view right over our fields to Dale End. All on a sudden, Dad picked me up and swung me on to his shoulders.

‘Tek a good look at that land, Betsy,’ he said. ‘Don’t matter a toss now that tha’s only a lass. Soon there’ll be nowt here for any bugger to work at, save only the fishes.’

I’d no idea what he meant, but it were grand for him to be taking notice of me for a change, and I recall how his bony shoulder dug into my bare legs, and how his coarse springy hair felt in my little fists and how he smelt of sheep and earth and hay.

I think he forgot I were up there till I got a bit uncomfortable and moved. Then he gave a little start and said, ‘Things to do still. Nowt stops till all stops.’ And he dropped me to the floor with a thump and slid down the ladder. That were typical. Telling me off for being up there one minute then forgetting my existence the next.

I stayed up a long while till Mam started shouting for me. She caught me clambering down the ladder and gave me a clout on my leg and yelled at me for being up there. But I said nowt about Dad ’cos it wouldn’t have eased my pain and it would just have got him in bother too.

Time went on. A year maybe. Hard to say. That age a month can seem a minute and a minute a month if you’re in trouble. I know I got started at the village school. That’s where most of my definite memories start too. But funny enough, I still didn’t have any real idea what them men were doing down at Dale End. I think I just got used to them. It seemed like they’d been there almost as long as I had. Then some time in my second year at school, I heard some of the older kids talking about us all moving to St Michael’s Primary in Danby. We hated St Michael’s.

We just had two teachers, Mrs Winter and Miss Lavery, but they had six or seven and one of them was a man with a black eye-patch and a split cane that he used to beat the children with if they got their sums wrong. At least that’s what we’d heard.

I piped up and asked why we had to move there.

‘Dost know nowt, Betsy Allgood?’ asked Elsie Coe, who was nearly eleven and liked the boys. ‘What do you think they’re building down the dale? A shopping centre?’

‘Nay, fair do’s,’ said one of her kinder friends. ‘She’s nobbut a babbie still. They’re going to flood all of Dendale, Betsy, so as the smelly townies can have a bath!’

Then Miss Lavery called us in from play. But I went to the drinking fountain first and watched the spurt of water turn rainbow in the sun.

After that I started having nightmares. I’d dream I were woken by Bonnie sitting on my pillow and howling, and all the blankets would be wet, and the bed would be almost floating on the water which were pouring through the window. I’d know it were just a dream, but it didn’t stop me being frightened. Dad told me not to be so mardy and Mam said if I knew a dream were just a dream I should try and wake myself up, and sometimes I would, only I wouldn’t really have woken up at all and the water would still be there, lapping over my face now, and then I really would wake up screaming.

When Mam realized what were troubling me, she tried to explain it all. She were good at explaining things when she wasn’t having one of her bad turns. Nerves, I heard Mrs Telford call it one day when I was playing under the window of the joiner’s shop at Stang with Madge. It was Mrs Telford I heard say too that it were a pity Jack Allgood (that’s my dad) hadn’t got a son, but it didn’t help anyone Lizzie (that’s my mam) cutting the girl’s hair short like a boy’s and dressing her in trousers. That was me. I looked in the mirror after that and wondered if mebbe I couldn’t grow up to be a boy.

I was saying about my mam explaining things. She told me about the reservoir and how we were all going to be moved over to Danby, and it wouldn’t make all that much difference ’cos Dad were such a good tenant, Mr Pontifex had promised him the first farm to come vacant on the rest of his estate over there.

Now the nightmares faded a bit. The idea of moving were more exciting than frightening, except for the thought of that one-eyed teacher with the split cane. Also the weather had turned out far too good for young kids to worry about something in the future. Especially about too much water!

That summer were long and hot, I mean really long and hot, not just a few kids remembering a few sunny days like they lasted forever.

Winter were dry, and spring too, apart from a few showers. After that, nothing. Each day hotter than last. Even up on Beulah Height you couldn’t catch a draught, and down in the dale we kept all the windows in the house and school wide open, but nought came in save for the distant durdum of the contractors’ machines at Dale End.

Fridays at school was the vicar’s morning when Rev Disjohn would come and tell us about the Bible and things. One Friday he read us the story about Noah’s Flood and told us that, bad as it seemed for the folks at the time, it all turned out for the best. ‘Even for them as got drowned?’ cried out Joss Puddle whose dad were landlord at the Holly Bush. Miss Lavery told him not to be cheeky, but Rev Disjohn said it was a good question and we had to remember that God sent the Flood to punish people for being bad. What he wanted to say was that God had a reason for everything, and mebbe all this fuss about the reservoir was God’s way of reminding us how important water really was and that we shouldn’t take any of his gifts for granted.

When you’re seven you don’t know that vicars can talk crap. When you get to be fourteen, you know, but.

Slowly day by day the mere’s level went down. Even White Mare’s Tail shrank till it were more like a white mouse’s. White Mare’s Tail, in case you don’t know, is the force that comes out of the fell near top of Lang Neb. That’s the steep fell between us and Danby. It’s marked Long Denderside on maps, but no one local ever calls it owt but Lang Neb, that’s because if you look at it with your head on one side, it looks like a nose, gradually rising till it drops down sudden to Black Moss col on the edge of Highcross Moor. On the other side it rises up again but more gradual to Beulah Height above our farm. There’s two little tops up there and because they look a bit like a mouth, some folk call it the Gob, to match the Neb opposite. But Mrs Winter said we shouldn’t call it owt so common when its real name was so lovely, and she read us a bit from this book that Beulah comes into. Joss Puddle said it were dead boring and he thought the Gob were a much better name. But I liked Beulah ’cos it were the same as our farm and besides it sort of belonged to us, seeing as my dad had the fell rights for his sheep up there and he kept the fold between the tops in good repair, which Miss Lavery said was probably older than our farmhouse even.

Any road, no one could deny our side of the valley were much nicer than Lang Neb side, which was really steep with rocks and boulders everywhere. And in the rainy season, while there’d be becks and falls streaking all of the hillsides, on the Neb they just came bursting straight out of fell, like rain from a blocked gutter. Old Tory Simkin used to say there were so many caves running through the Neb, there was more water than rock in it. And he used to tell stories about children falling asleep in the sunshine on the Neb, and being taken into the hill by nixes and such, and never seen again.

But he stopped telling the stories when it really started happening. Children disappearing, I mean.

Jenny Hardcastle were the first. Holidays had just started and we were all splashing around in Wintle Pool where White Mare’s Tail hits fell bottom. Usually little ones got told off about playing up there, but now the big pool were so shallow even the smallest could play there safe.

They asked us later what time Jenny left, but kids playing on a summer’s day take no heed of time. And they asked if we’d seen anyone around, watching us or owt like that. No one had. I’d seen Benny Lightfoot up the fell a way, but I didn’t mention him any more than I’d have mentioned a sheep. Benny were like a sheep, he belonged on the fell, and if you went near him he’d likely run off. So I didn’t mention him, not till later, when they asked about him particular.

My friend Madge Telford said that Jenny had told her she was fed up of splashing around in the water all day like a lot of babbies and she were going to Wintle Wood to pick some flowers for her mam. But Madge thought she were really in a huff because she liked to be centre of attention and when Mary Wulfstan turned up we all made a fuss of her.

You couldn’t help but like Mary. It weren’t just that she were pretty, which she was, with her long blonde hair and lovely smile. But she were no prettier than Jenny, or even Madge, whose hair was the fairest of them all, like the water in the mere when the sun’s flat on it. But Mary were just so nice you couldn’t help liking her, even though we only saw her in the holidays and at weekends sometimes.

She were my cousin, sort of, and that helped, her mam belonging to the dale and not an offcomer, though they did only use Heck as a holiday house now. Mary’s granddad had been my granddad’s cousin, Arthur Allgood, who farmed Heck Farm which stood, the house I mean, right at mere’s edge just out of bottom end of the village. Mary’s mam was Arthur’s only child and I daresay were reckoned ‘only a girl’ like me. But at least she could make herself useful to the farm by getting wed. Next best thing after a farmer son is a farmer son-in-law, if you own the farm, that is. Arthur Allgood owned Heck, but our side of the family were just tenants at Low Beulah, and while a son could inherit a tenancy, a daughter’s got no rights.

Not that Mary’s mam, Aunt Chloe (she weren’t really my aunt, but that’s what I called her) married a farmer. She married Mr Wulfstan, who’s got his own business, and they sold off most of the Heck land and buildings to Mr Pontifex, but they kept the house for holidays.

Mr Wulfstan were looked up to rather than liked in the dale. He weren’t stand-offish, my mam said, just hard to get to know. But when he had Heck done up to make it more comfortable, and got the cellar properly damp-proofed and had racks set up there to keep his fine wines, he gave as much work locally as he could, and people like Madge’s dad, who ran the dale joinery business at Stang with his brother, said he were grand chap.

But I’m forgetting Jenny. Maybe she did go off in a huff because of Mary or maybe that was just Madge making it up, and she really did go off to pick some flowers for her mam. That’s where they found the only trace of her, in Wintle Wood. Her blue suntop. She could have been carrying it and just dropped it. We took everything but our pants off when we played in the water in them hot days and we were in no hurry to get dressed again till we got scolded. We ran around the village like little pagans, my mam said.

But that all stopped once police were called in. It was questions questions then and we all got frightened and excited, but mebbe more excited to start with. When sun’s shining and everything looks the same as it always did, it’s hard for kids to stay frightened for long. Also Jenny were known for a headstrong girl and she’d run off before to her gran’s at Danby after falling out with her mam. So mebbe it would turn out she’d run off again. And even when days passed and there were no word of her, most folk thought she could have gone up the Neb and fallen down one of the holes or something. The police had dogs out, sniffing at the suntop, but they never found a trail that led anywhere. That didn’t stop Mr Hardcastle going out every day with his collies, yelling and calling. They had two other kids, Jed and June, both younger, but the way he went on, you’d have thought he’d lost everything in the world. My dad said he never were much of a farmer, but now he just didn’t bother with Hobholme, that’s their farm, though as he were one of Mr Pontifex’s tenants like Dad and the place would soon be drowned, I don’t suppose it mattered.

As for Mrs Hardcastle, you’d meet her wandering around Wintle Wood, picking great armfuls of flopdocken which was said to be a good plant for bringing lost children back. She had them all over Hobholme and when it were her turn to take care of flowers in the church, she filled that with flopdocken too, which didn’t please the vicar, who said it was pagan, but he left them there till it were someone else’s turn the following week.

The rest of the dale folk soon settled back to where they were before. Not that folk didn’t care, but for us kids with the weather so fine, it were hard for grief to stretch beyond a few days, and the grown-ups were all much busier than we ever knew with making arrangements for the big move out.

It were only a matter of weeks away but that seemed a lifetime to me. I’d picked things up, more than I realized, and a lot more than I really understood. And the older girls like Elsie Coe were always happy to show off how much they knew. She it was who told me that there were big arguments going on about compensation, but it didn’t affect me ’cos my dad were only a tenant, and Mr Pontifex had sold Low Beulah and Hobholme along with all the rest of his land in Dendale and up on Highcross Moor long since. Some of the others who owned their own places were fighting hard against the Water Board. Bloody fools, my dad called them. He said once Mr Pontifex sold, there were no hope for the rest and they might as well go along with the miserable old sod. Mam told him not to talk like that about Mr Pontifex, especially as he’d been promised first vacant farm on the Danby side of the Pontifex estate, and she’d heard that Stirps End were likely to be available soon. And Dad said he’d believe it when it happened, the old bugger had sold us out once, what was to stop him doing it again?

He talked really wild sometimes, my dad, especially when he’d been down at the Holly Bush. And Mam would either cry or go really quiet, I mean quiet so you could have burst a balloon against her ear and she’d not have heard. But at least when she were like this I could run around all day in my pants or in nothing at all and she’d not have bothered. Or Dad either.

Then Madge, my best friend, got taken. And suddenly things looked very different.

I’d gone round to play with her. Mam took me. She were having one of her good days and even though most folk reckoned that Jenny had just fallen into one of the holes in the Neb, our mams were still a bit careful about letting us wander too far on our own.

The Stang where Mr Telford had his joiner’s shop were right at the edge of the village. Even though it were a red-hot day, smoke was pouring from the workshop chimney as usual, though I didn’t see anyone in there working. We went up the house and Mrs Telford said to my mam, ‘You’ll come in and have a cup of tea, Lizzie? Betsy, Madge is down the garden, looking for strawberries, but I reckon the slugs have finished them off.’

I went out through the dairy into the long narrow garden running up to the fellside. I thought I saw someone up there but only for a moment and it probably weren’t anyone but Benny Lightfoot. I couldn’t see Madge in the garden but there were some big currant bushes halfway down, and I reckoned she must be behind them. I called her name, then walked down past the bushes.

She wasn’t there. On the grass by the beds was one strawberry with a bite out of it. Nothing else.

I felt to blame somehow, as if she would have been there if I hadn’t gone out to look for her. I didn’t go straight back in and tell Mam and Mrs Telford. I sat down on the grass and pretended I was waiting for her coming back, even though I knew she never was. I don’t know how I knew it, but I did. And she didn’t.

Mebbe if I’d run straight back in they’d have rushed out and caught up with him. Probably not, and no use crying. There was a him now, no one had any doubt of that.

Now there were policemen everywhere and all the time. We had our own bobby living in the village. His name was Clark and everyone called him Nobby the Bobby. He was a big fierce-looking man and we all thought he was really important till we saw the way the new lot tret him, specially this great glorrfat one who were in charge of them without uniforms.

They set up shop in the village hall. Mr Wulfstan made a right fuss when he found out. Some folk said he had the wrong of it, seeing what had happened; others said he were quite right, we all wanted this lunatic caught, but that didn’t mean letting the police walk all over us.

The reason Mr Wulfstan made a fuss was because of the concert. His firm sponsored the Mid-Yorkshire Dales Summer Music Festival, and he were head of the committee. The festival’s centred on Danby. I think that’s how he met Aunt Chloe. She liked that sort of music and used to go over to Danby a lot. After they got wed and she inherited Heck, he got this idea of holding one of the concerts in Dendale. They held them all over, but there’d never been one here because there were so few people living in the dale and the road in and out wasn’t all that good. The Parish Council had held a public meeting to discuss it the previous year. Some folk, like my dad, said they cared nowt for this sort of music and what were the point of attracting people up the valley when in a year or so there’d be nowt for them to see but a lot of water? This made a lot of folk angry (so I were told) ’cos things hadn’t been finally settled and they were still hopeful Mr Pontifex would refuse to sell. Not that that would have made any difference except to drag things out a little longer. But the vote was to accept the concert, specially when Mr Wulfstan said he’d like the school choir to do a turn too.