скачать книгу бесплатно

“Excited,” Monique says definitively. “We’re like some new super-species!”

After that it’s impossible to go back to sleep, so Sasha gets up and gets dressed and goes to meet Carson and the real estate agent. She’s only fifteen minutes late, which is really only five minutes late for her, but she can see as she approaches that the agent is tense, though Carson looks relaxed.

“Hello,” Sasha says, as she walks up to the building’s entrance, where they are waiting for her.

“You must be Sasha,” the real estate agent says. She’s a woman in her thirties with spiky brown hair and Sasha can tell from her expression that she was expecting Sasha to be different somehow, more sophisticated, maybe. She wonders if that’s going to be her life from now on if she stays with Carson, people expecting her to be something she’s not.

The apartment is on the third floor of a building on East Sixty-seventh Street, directly across from an ice cream store called Peppermint Park. These are both strikes against it because Sasha has always felt she doesn’t belong on the Upper East Side, and besides, how much weight would she gain with an ice cream parlor right across the street?

But she and Carson and the real estate agent go up and tour the apartment, and Sasha decides that the main thing wrong with it is that there’s nothing wrong with it. She and Monique concluded long ago that you’re not really living in New York unless there’s something wildly negative about your apartment, like the one they lived in where the shower was in the kitchen, or the one in the building The New York Times dubbed “the house of horrors” because so many people committed suicide there. In their current apartment, you can roll a marble downhill from the front door to the back of the kitchen.

The real estate agent says, “I know Carson especially liked this place because it has a room for you to write in. It’s just a little hidey-hole, but I think you’ll like it.”

The real estate agent leads her to an extremely small sunny room with a perfectly square window, and just enough space for a desk and a writer. Currently, Sasha has no desk, she has to use the kitchen table after she clears Monique’s breakfast dishes off it, and the only view is across the air shaft into their neighbor’s kitchen. This has never bothered Sasha, though. She does not even know where she is ten minutes after she starts typing.

She walks over and looks out the window of the hidey-hole, wishing that the stupid real estate agent had not called it that because now she doubts she can ever think of it any other way.

Carson comes up behind her and puts his arms around her. “Do you like this room?”

“I love it,” Sasha says. But really, she is thinking that Monique would love it. She would love that Carson chose an apartment with a room for Sasha to write in. Finally, he has done something Monique would approve of and this thought gives Sasha a little stab of sorrow, as sharp as a splinter.

Carson rests his chin on the top of her head and Sasha leans back against him. Across the street, a man and four children have come out of Peppermint Park, and the man is holding four cones and some napkins, while the children jump up and down around him like pigeons around a picnicker.

“They look happy, don’t they?” Carson asks.

“Yes,” Sasha says softly, but she is wondering how anyone else can think they are happy at this particular moment, when she alone knows the meaning of happiness. She holds it right now in the palm of her hand.

HOW TO GIVE THE WRONG IMPRESSION (#ulink_a4a24cae-400f-5cfe-bc73-9223c51727fd)

You never refer to Boris as your roommate, although of course that’s exactly what he is. You’re actually apartment mates and you only moved in together the way any two friends move in together for the school year, nothing romantic. Probably Boris would be horrified if he knew how you felt. You’re a psych major, you know this is unhealthy, but when you speak of him you always say Boris, or, better yet, This guy I live with. He may be just your roommate but not everyone has to know.

You buy change-of-address cards with a picture on the front, of a bear packing a trunk. You send them to your friends and your parents. After some hesitation, you write “Boris and Gwen” on the back, above the address. After all, he does live here.

You help Boris buy a bed. This is a great activity for you, it’s almost like being engaged. You lie on display beds with him in furniture stores. Toward the end of the day, you are tired and spend longer and longer just resting on the beds.

Boris lies next to you, telling you about the time his sister peed in a display toilet at Sears when she was three. You glance at him sideways. He looks tired, too, although the whites of his eyes are still bright—the kind of eyes you thought only blue-eyed people had, but his eyes are brown.

A salesman approaches, sees you, smiles. He knocks on the frame of the bed with his knuckles. “Well, what do you folks think?” he asks.

Boris turns to you. You ask the salesman about interest rates, delivery fees, assembly charges. You never say, Well, it’s your bed, Boris, in front of the salesman.

When your parents come through town and offer to take you and Boris out to dinner, you accept. But this is risky, this all depends on whether you’ve implied anything to your parents beyond what was on the change-of-address card. You think about it and decide it’s pretty safe, but you spend a great deal of time hoping your father will not ask Boris what his intentions are.

Boris, love of your life, goes to the salad bar three times and doesn’t stick a black olive on each of his fingers, a thing he often does at home. On the way out, he holds your hand. You are the picture of young love. Boris may make the folks’ annual Christmas letter.

You always have boyfriends. You try to get them taller than Boris, but it’s not easy. Sometimes after they pick you up, they roll their shoulders uncomfortably in the elevator and say, “Gwen, I think Boris is going to slash my tires or something, he’s so jealous.”

Snort. “Oh, please,” you say. Later, during a lull in the conversation, you ask casually, “What makes you think Boris is jealous of you?” One of your boyfriends says it’s because Boris found six hundred excuses to come into the living room while you two were drinking wine. Another one says it’s the way Boris shook hands with him. This is interesting. You were still in your bedroom when that happened.

Whatever they answer, you file it away and replay it later in your mind.

You always encourage Boris to ask Dahlia Kosinski out.

When he comes back from his ethics study group and says, “Oh, my God, Dahlia looked so incredibly gorgeous tonight,” you do not say, I heard she almost got kicked out of the ethics class for sleeping with the professor. You say, “I think you should ask her out.”

“Noooo,” Boris says, drawing circles on the kitchen table with his pencil.

“Sure,” you say. “Just pick up the phone.” In fact, you do pick up the phone. You call information and get Dahlia’s number. Say, “Want me to dial?”

Boris shakes his head. “Let’s go get something to eat,” he says. He puts his arms around you and dances you away from the phone. You think that Dahlia Kosinski is probably too tall for Boris’s chin to rest on her head like this.

You didn’t write Dahlia’s phone number down on the scratch pad by the phone when you called information, because you don’t need Boris looking at it and mulling it over when you’re not around. This whole procedure is nerve-racking, but not to worry—he’ll never ask her out, and it’s always, always better to know than to wonder.

In Pigeon Lab, you name your pigeon after him because the two other women who work there name their pigeons after their husbands. You spend a lot of time making fun of Boris when these two women make fun of their husbands. This, as a matter of fact, is not hard to do.

You tell them about how he keeps a flare gun in the trunk of his car. Ask them how many times they think his car is going to break down in the middle of the Mojave Desert or at sea.

You tell them that he has this thing for notebooks. He keeps one in the glove compartment of his car and records all this information in it whenever he fills the gas tank. You say, “I mean, there can be four hundred cars behind us at the gas station, honking, and there’s Boris, frantically scribbling down the number of gallons and the price and everything.”

They are so amused by this that you tell them he has another notebook where he records all the cash he spends. You say, “If he leaves a waitress two dollars, he runs home and writes it down.” You add, “I’m surprised he doesn’t also record the serial numbers.”

Because this last part isn’t even about Boris, it’s about your father, you worry that you are becoming a pathological liar.

You never act jealous in front of Linette, his best friend from undergrad. She spends the day at your apartment on her way to a game she’s going to be in. She plays basketball for some college in California.

She is as tall and slender as you feared and not as coarse and brawny as you wanted. You had hoped she would lope around the apartment, pick you up, and chuck you to Boris, saying, Well, Bo, I guess we could toss a little thing like her right through the hoop.

Actually, Boris and Linette do go play some basketball, and when they come back, you all sit on the couch and drink beer. Linette puts her hand on Boris’s thigh, which is lightly sweating, and you hope it’s just from basketball. You resist the urge to put your hand on his other thigh. You imagine yourself and Linette frantically claiming Boris’s body parts, slapping your hands on his legs, then his arms, then his chest. Only knowing how much pleasure he would get out of this keeps you from doing it.

Instead, you finish your beer in one long swig, anxious to show that you can drink right along with any basketball player, and you rise. You say, “It’s been nice to meet you, Linette, but I have to go, I have a date.” You don’t have boyfriends anymore, just dates.

“Yes,” you say again, “I have to go get ready.” You say this so Linette will believe that you are looking the way you normally look around the house, that you are actually about to go make yourself better-looking. She does not need to know that you’re already wearing a lot of makeup, that this is about as good as it gets.

You pretend you don’t want to kiss him. He calls from a bar on Halloween, too drunk to drive, when you are home studying. You drive to pick him up, wearing sweats and your glasses. You wear your glasses only on nights when you don’t plan to see him.

He sings on the ride home, pulling on your braid. Wonder why he’s in such a good mood. Was Dahlia Kosinski at this bar?

In the kitchen, he drinks your orange juice out of the carton. You say, “Put that back.”

Boris says, “Too late,” and holds the carton upside down to demonstrate. Three drops of orangey water fall on the floor.

“Damn,” you say and throw the sponge on the floor. This is a good indication of how irritable you are, because the floor was already sticky enough to rip your socks off.

“I’m sorry, Gwen,” Boris says. “I’ll go get more tomorrow, I promise.”

“Forget it,” you say, rubbing the sponge around with your toe.

“If you forgive me, I’ll kiss you,” Boris says.

Now you don’t even have to pretend you don’t want to kiss him, because, you have to face it, that was pretty obnoxious.

“Oh, spare me,” you say, and cross your arms over your chest. Boris leans over and kisses you on the eyebrow. Don’t in any way change your posture, but you can close your eyes.

He touches your lips with his tongue. Wonder why you have to suffer this mutant behavior on top of everything else. He must look like someone trying to be the Human Mosquito. Does this even count as a kiss? This is a very good question, and you will spend no small amount of time pondering it.

Boris cuts himself shaving and leaves big drops of blood on the sink. You approach cautiously; it looks as if a small animal had been murdered.

You consider your options. You could point silently but dramatically at the sink when Boris returns. You could leave him an amused but firm note: “Dear Boris, I don’t even want to know what happened in here …” Or you can do nothing and assume that he’ll eventually do something about it. That is probably your best option. But what if he thinks you left it there? What if he thinks you shave your legs in the sink or something? Best to clean it up and not mention it.

This you do, pushing a paper towel around the sink with a spoon.

You take Boris home for Thanksgiving dinner. All goes smoothly except for your grandmother glaring at him after the turkey is carved and announcing, “The one thing I will not tolerate is this living together, and I say that aloud for all the young people to hear.”

Boris looks up from his turkey drumstick like a startled wolf cub, a spot of grease smeared on his cheek.

Later, when you are walking back toward the train station, he says, “What did your grandmother mean by that?”

Hoot. You say, “I don’t know, but the way she said ‘all the young people’ made it sound like there were a whole group of young people, drinking beer or something.”

Boris is not to be distracted. “The thing is,” he says, “we aren’t living together in that way.”

You try not to wince. You do shiver. You take Boris’s hand as he bounds along on his long legs, your signal that he has to either slow down or pull you along. He tucks both your hand and his hand into the pocket of his jacket. You look up at his face out of the corner of your eye. In the cold, you watch him breathe perfect plumes of white that match the sheepskin lining of his jacket. You think how happy you would be if Boris thought you were half as beautiful as you think he is at this moment.

You walk this way for a few minutes. Then he tells you that your hand is sweating, making a lake in his pocket, and gives you his gloves to wear.

You take to going out with Boris for frozen yogurt almost every night at about midnight. You are always the last people in the yogurt place, and the guy who works there closes up around you. Tonight Boris says, “Gwen, you have hot fudge in the corner of your mouth,” and wipes it away, hard, with the ball of his thumb. Wonder if you feel too comfortable with him to truly be in love.

But then he licks the fudge off his thumb and smiles at you, his hair still ruffled from the wind outside. He is the love of your life, no question about it.

For Christmas, you buy Boris a key chain. This is what you had always imagined you would give a boyfriend someday, a key chain with a key to your apartment. Only it’s not exactly a parallel situation with Boris, of course, in that he’s not your boyfriend and he already has a key to your apartment, because he lives there. Okay, you admit it, there are no parallels other than that you are giving him a key chain.

Still, you can tell the guy in the jewelry store anything you like. Go ahead, say it: “This is for my boyfriend, do you think he’ll like it?”

For Christmas, Boris gives you a framed poster of the four major food groups. You amuse yourself by trying to think of one single more unromantic gift he could have given you. You amuse yourself by wondering if you can make this into an anecdote for the women in Pigeon Lab.

When people ask you what Boris gave you for Christmas, you smile shyly and insinuate that you were both too broke to afford much.

The girls in Pigeon Lab have a Valentine’s Day party and invite you and Boris. Probably you shouldn’t show him the invitation, since his name is on it and he might wonder why you and he are invited as a couple. Just say, “Look, I have a party to go to, want to come?”

“Sure,” Boris says, and the best part of the whole thing is that this way you know without asking that he doesn’t have plans with someone else.

You don’t have boyfriends anymore, and these days you don’t even have dates. You tell Boris this is because you have too much work to do, and often on Saturday nights you make a big production of hauling your Psychology of Women textbook out to the sofa and propping it on your lap, even though it hurts your thighs and you never read it.

Instead, you talk to Boris, who is similarly positioned on the other end of the sofa, his feet touching yours. Sometimes he lies with his head in your lap and falls asleep that way. You never get up and leave him; you stay, touching his hair, idly clicking through the channels, watching late-night rodeo.

One night Boris wakes up during the calf roping. “Oh, my God,” he says, watching a calf do a four-legged split, its heavy head wobbling. “This is breaking my heart.”

This thing with Dahlia Kosinski reminds you of a book you read as a child, Good News, Bad News.

The good news is the ethics study group has a party and Boris invites you to go. The bad news is that Dahlia Kosinski is there and she’s beautiful in a careless, sloppy way you know you never will be: shaggy black hair, too much black eyeliner, a leopard-print dress with a stain on the shoulder. You know that her nylons have a big run somewhere and she doesn’t even care. The good news is that Dahlia has heard of you. “Hello,” she says. “Are you Gwen?” The bad news is that she makes some joke about a book she read once called Gwendolyn the Miracle Hen, and Boris laughs. The good news is that Dahlia has what appears to be a very serious boyfriend. The bad news is that they have a fight in the bathroom, so maybe they’re not really in love. The worse news is that in the car on the way home Boris says, “I don’t think Dahlia will ever leave that boyfriend of hers. Everyone I’ve talked to says they’re very serious.” Which means that he’s looked into Dahlia’s love life, he’s made inquiries. Wonder how there can be bad news followed by worse news. Does that ever happen in the book? Bad news: You’re pushed out of an airplane. Worse news: You don’t have a parachute?

Boris tells you that one night he stopped by the frozen yogurt place without you and the guy behind the counter made some sort of pass at him and wanted to know if you were Boris’s girlfriend.

Ask, “What did you tell him?”

“What choice did I have?” Boris says in a tone that crushes you like a grape.

Linette stops by again. This time she spends the night, disappearing into Boris’s room with a six-pack. You hear them laughing in there. Whatever else you do, call someone and go out that night.

When you are in the kitchen the next morning, Boris wanders out. You ask him how he feels. “Tired,” he says. “Linette kept me up all night talking about whether she should go to grad school or not.”

Wonder if he’s telling the truth. Say, “Should she?”

“God, no,” Boris says. “She’s such a birdbrain.”

“Oh,” you say loudly, over the banging of your heart.

You clean the bathroom late one night after Boris has gone to bed. You wear a T-shirt and a pair of Boris’s boxer shorts that you stole out of a bag of stuff he’s been planning to take to the Salvation Army. It gives you immense pleasure to wear these boxer shorts, but you wear them only after he’s gone to bed, and you never sleep in them. You do have some pride.

Your cleaning is ambitious: you wipe the tops of the doors, the inside of the shower curtain; you even unscrew the drain and pull out a hair ball the size of a rat terrier. It is so amazing that you consider taking a picture with your smiling face next to it for size reference, but in the end you just throw it out.

You are standing on the edge of the tub, balancing a bowl of hot, soapy water on your hip and swiping at the shower-curtain rod with a sponge when Boris walks in and says, “Well, hello, Mrs. Clean.”

You smile. He yawns. “Do you need some help?” he says.

You let him hold the bowl of water while you turn your back to him and reach up and run the sponge along the shower-curtain rod.

“I never knew you had to clean those,” Boris says. “I can’t believe it’s one in the morning. I feel like we’re married and this is our first apartment or something.”

Your throat closes. Until this moment you had not thought about the fact that this was your and Boris’s first apartment, that once the lease is up there might not be a second apartment, and you might not see him every day.

“Hey,” says Boris. “You’re wearing my boxer shorts.” He puts the bowl of water on the sink and turns the waistband inside out so he can read the tag. “They are!” he says, delighted.

You freeze. Clear your throat. “Yeah, well,” you say.

Even standing on the edge of the tub, you are only a few inches taller than Boris, and he slides an arm around your waist. He brushes your hair forward over your shoulders and traces a V on your back for a long moment, as though you were a mannequin and he were a fashion designer contemplating some new creation.

Then you feel him kiss the back of your neck above your T-shirt. You remember Halloween and think about saying, Boris, are those your lips? but you don’t. You don’t do anything. You still haven’t moved; your arms are over your head, hands braced against the rod.

“You’re so funny, Gwen,” Boris whispers against your skin.

“Really?” you say. A drop of soapy water lands on your eyelid, soft as cotton, warm as wax. “Me?”

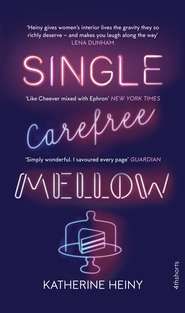

SINGLE, CAREFREE, MELLOW (#ulink_46a6bca8-4cb9-5bd6-a520-817f4f06e03f)

You could sum it up this way: Maya’s dog was dying, and she was planning to leave her boyfriend of five years. On the whole, she felt worse about the dog.

“God, that’s horrible,” said Rhodes, Maya’s boyfriend. “I don’t know if I can stand it. There’s really nothing we can do?”