Полная версия:

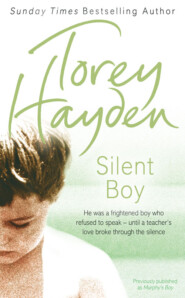

Silent Boy: He was a frightened boy who refused to speak – until a teacher's love broke through the silence

Torey Hayden

Silent Boy

He was a frightened boy who

refused to speak – until a teacher’s

love broke through the silence

Dedication

To S. K.

for teaching me to cherish the

brutal privilege of being human

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Part I

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Part II

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty–one

Chapter Twenty–two

Chapter Twenty–three

Chapter Twenty–four

Chapter Twenty–five

Chapter Twenty–six

Chapter Twenty–seven

Chapter Twenty–eight

Chapter Twenty–nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty–one

Part III

Chapter Thirty–two

Chapter Thirty–three

Chapter Thirty–four

Chapter Thirty–five

Chapter Thirty–six

Chapter Thirty–seven

Chapter Thirty–eight

Exclusive sample chapter

About the Author

Torey Hayden

Copyright

About the Publisher

Chapter One

Zoo-boy. The legs of the table were his cage. With arms up protectively over his head, he rocked. Back and forth, back and forth. An aide tried to prod him into moving out from under the table but she had no luck. Back and forth, back and forth the boy rocked.

I watched from behind the one-way mirror. ‘How old is he?’ I asked the woman on my right.

‘Fifteen.’

Hardly a boy anymore. I leaned close to the glass to see him. ‘How long has he been here?’ I asked.

‘Four years.’

‘Without ever speaking?’

‘Without ever speaking.’ She looked over at me in the eerie gloom of the room behind the mirror. ‘Without ever making a noise at all.’

I continued to watch a little longer. Then I picked up my box of materials and went out into the room on the other side of the mirror. The aide backed off and, when I entered, she willingly left. I could hear the click of a door in the outer corridor and I knew she had gone behind the mirror to watch too. Only Zoo-boy and I were left in the room.

Carefully, I set down my box of materials. I waited a moment to see if he would react to a new person in the room, but he didn’t. So I came closer. I sat down on the floor an arm’s length away from where he had barricaded himself under the table. Still he rocked, his arms and legs curled up around him. I could get no idea of his stature.

‘Kevin?’

No response.

Not sure what to do, I looked around. I was acutely aware of the audience beyond the mirror. They were talking in there, their voices indistinct, no more than an undulating murmur, like wind through cattails on a summer’s afternoon. But I knew the sound for what it was.

The boy didn’t look fifteen. Even wrapped up in a ball like that where I couldn’t get much of a look at him, he didn’t appear that old. Nine, maybe. Or eleven. Not nearly sixteen.

‘Kevin,’ I said again, ‘my name is Torey. Do you remember Miss Wendolowski telling you someone was coming out to work with you? That’s me. I’m Torey and I work with people who have a hard time talking.’

Still he rocked. I wasn’t given even the slightest acknowledgment. All around us hung a heavy, cloying silence embroidered with the rhythmic sound of his body hitting against the linoleum.

I started to talk to him, keeping my voice soft and welcoming, the way one talks to timid puppies. I talked of why I had come, of what I was going to be doing with him, of other children whom I had worked with and had success. I told him about myself. What I said wasn’t important, only the tone was.

No response. He only rocked.

The minutes slipped away. I was running dry of things to say. Such a one-sided conversation was not easy to maintain, but what made it more difficult was not Zoo-boy so much as the ghostly presence of those beyond the mirror. It was too easy to feel stupid talking to oneself when half a dozen people one couldn’t see were watching. Finally, I pulled over my box of materials and sorted out a paperback book, a mystery story about a teenager and his girl friend. I’ll read to you, I told Zoo-boy, until we feel a little more relaxed with one another.

‘Chapter One:The Long Road.’

I read.

And read.

The minutes kept moving around the face of the clock. Occasionally there was the muffled noise of a door opening and closing beyond our little room. They were leaving, one by one. Nothing in here was worth wasting an afternoon to see. I was not a spectacular reader. The story wasn’t riveting. And Zoo-boy only rocked.

I kept on reading. And counting the openings and closings. How many people had been in the room behind the mirror? I couldn’t recall exactly. Six? Or was it seven? And how many had gone out already? Five?

I read on.

Click-click. Another gone.

Click-click. That was seven.

I continued to read. My voice became the only sound in the room. I looked over. Zoo-boy had stopped rocking. Slowly he brought his arms down to see me better. He smiled. He was nobody’s fool. He had been counting too.

He gestured at me, a small movement within the confines of the table and chairs.

‘What?’ I asked, because I couldn’t understand what he was trying to communicate.

He gestured again, more widely this time. Only it wasn’t just a simple motion. Rather, it was a sentence, a paragraph almost, of gestures.

I still couldn’t understand. I moved a chair aside to see him better but I had to ask him to repeat it.

There was something he wanted me to know. The motions were poetic in their gyrating, wreathing urgency. A hand ballet. But they were no sign language I understood, not Ameslan, not the hand alphabet. I couldn’t comprehend at all.

From under the table came a deep sigh. He grimaced at me. Then patiently he repeated his gestures again, more slowly this time, more emphatically, like someone speaking to a rather stupid child. He became frustrated when he could not make me understand.

Finally, he gave up. We sat in silence, staring at one another. The book was still in my hands, so in desperation to fill the time, I asked him if he’d like me to read a little more. Zoo-boy nodded.

I settled back against the wall. ‘Chapter Five: Out of the Cave.’

Zoo-boy pushed the other chair slightly out from the table and reached to touch the cloth of my jeans. I looked up.

He had his mouth open, one hand pulling the lower jaw down. He pointed down his throat. Then dismally, he shook his head.

Chapter Two

For a little over a year I had been working at the clinic as a research psychologist. Most of my professional life had been spent as a teacher. While in education I had held a variety of positions, running the full gamut from teaching a regular first-grade class to teaching graduate-level university students, from working in an open-plan progressive school to working in a locked classroom on the children’s unit of a state mental institution. I loved teaching. I always had; I still did. But then, as years passed, the general philosophies, particularly in special education, began to shift and I grew to feel like a stranger in my own world.

At that point I decided to work on a doctorate in special education. I’m not sure why. I never particularly wanted the degree itself, it would overqualify me and I could never return to the classroom with it. And no other aspect of education appealed to me. I certainly would never make an administrator. But I went ahead and started the doctorate anyway. In the final analysis I suppose it was simply something to do while I tried to decide what direction my life should take next.

In my deep heart of hearts I was hoping that the philosophical pendulum would swing again in education and I could return to the classroom without compromising my own beliefs. However, as I dragged out my studies over four years, the change did not come, and I was faced with the brutal decision either of actually getting the degree and slamming shut the classroom door forever or of leaving the whole thing messily unfinished and trying something new. In the end, I chose the latter route because I just couldn’t confront the thought of never being able to return to teaching in the future. So I moved away from Minneapolis and the university with nothing to show for my four years there.

Throughout my career I had been working on research into a little-known psychological phenomenon known as elective mutism. This is an emotional disturbance occurring primarily in children. The child is physically capable of speaking but for psychological reasons refuses to do so. Most of these youngsters actually do speak somewhere, usually at home with their families, but they are voluntarily mute everywhere else. Over the years I had accrued a large body of data on this problem and developed treatment methods. Thus, when I saw an advertisement for a child psychologist, a research position with some clinical work, it seemed a reasonable solution to the difficulties I was having with my own field.

As the months passed, I found I was happy enough in my work at the clinic, but it was different from teaching. The children were parceled out to me, mostly by virtue of their language or lack of it, since that was my specialty. But they were never my children. In the few hours a week that I saw them, each individually, there was no opportunity for that small, self-contained civilization to develop when the door to the outer world was closed.

The clinic, however, did provide a lot of advantages. It was pleasant to be in the company of adults again for the major part of my working day. It wasn’t so much because I preferred their company but rather for the side benefits. I could wear decent clothes and put on makeup and not worry if some kid was going to spit up on my dry-clean-only blazer or escape the room because I wasn’t wearing my sure-grip track shoes. I could wear my long hair loose without worrying about someone pulling it out of my head. And perhaps best of all, I could wear skirts again. I didn’t need the freedom of movement and washability jeans provided, more to the point, my legs were not covered with bruises from being kicked constantly.

Association with my new colleagues at the clinic was reason enough to take the job. All of them were well educated, experienced, intelligent and expressive. There was always someone to kick an idea around with. In addition, there were other good points. I had magnificent facilities at my disposal, including a large, airy, sunlit therapy room, brand-new toys and equipment, a video recorder that worked, a computer down the hall and a statistician to go with it who spoke genuine English. Moreover, I had recognition for my work. I had a good salary. And I had more free time than I had ever had before. So, all in all, I was happy enough.

Then came Zoo-boy.

I hadn’t especially wanted the case. Right from the beginning the hopelessness shone through. One morning a social worker named Dana Wendolowski from the Garson Gayer Home had phoned the clinic in search of me. We have a boy for you, she told me, and the weary despair was a little too clear in her voice.

His name was Kevin Richter, although no one seemed to call him Kevin. He had earned his nickname because he spent all his waking hours under tables, chairs lined up in front of him and around the perimeter of the table until he was secure behind a protective barrier of wooden legs. There he sat, rocked sometimes, ate, did his schoolwork, watched TV. There he lived in his little self-built cage. Zoo-boy.

But Kevin’s problem went deeper than just an affinity for tables. He did not talk. He made no noise, even when he wept. The files claimed he had talked once upon a time, a long time ago. According to the sketchily drawn past in the Garson Gayer records, Kevin had never spoken at school when he’d attended. He was retained once and then twice because he did not talk to the teachers and no one knew whether or not he was learning. He had talked at home, at least that’s what the report said. And then he’d stopped. First he stopped talking to his stepfather, then a little later to his mother. Supposedly, he continued to speak to his younger sisters but by the time he was committed to the first residential treatment program, at nine, someone noticed Kevin was not speaking at all. No one could say exactly when he stopped talking. One day someone asked, and no one could remember the last time they had heard Kevin. And no one had heard him since.

Far more apparent than his lack of speech were Kevin’s fears. He lived in morbid, gut-wrenching fear of almost everything, his life was consumed by it. He feared highways and door hinges and spirals on notebooks and dogs and darkness and pliers and odd bits of string that might fall on the floor. He was too terrified of water to bathe; too superstitious of being without clothes to change them. And for the last three years Kevin had refused to set foot outside the door of the Garson Gayer residence. He had actually stayed inside all that time. Kevin’s fears had trapped him in a far more secure prison than he could ever have built with tables and chairs.

As the social worker told me these things I braced my forehead on one fist, the receiver of the phone in the crook of my neck. With my other hand I filled the margin of the desk blotter with doodles. The woman’s voice had a hurried desperation to it, as if she knew I would cut her short before she had said everything she needed to say.

Garson Gayer was a new facility, a model progressive institution. They had a full staff, including a resident psychologist, speech therapists, nurses and teachers. Why did they want me? I asked.

She had read about my work. She’d heard I worked with children who did not speak. I wondered aloud, Why, when there was so much wrong with this boy, had they decided to tackle his lack of speech? Well, you have to start somewhere, she replied, and her laugh was hollow. The phone grew quiet for a moment. Truth is, she said, it’s not quite like that. Kevin would be sixteen in mid-September and here it was, already late August. Garson Gayer only took children up through their fifteenth birthdays, so the rules had already been bent for him to allow him to stay this long. The state had custody of Kevin. And so far nothing they’d done for him at Garson Gayer had produced any improvement. If they couldn’t come up with something soon, well … She did not say it. She didn’t have to. We both knew the places boys like Kevin went, who had no family, no money, no hope.

He sounded like a lost cause right from the beginning. He had a lousy past. Very little useful data was recorded in the Garson Gayer file but there was enough to make Kevin’s childhood sound like so many others I had known. School failures, financial difficulties, physical abuse of Kevin and other children in the family, marital troubles, friction between Kevin and his stepfather, alcohol abuse, and perhaps most sinister of all, the fact that Kevin had been voluntarily given into state custody by his mother. What must a kid be like when even his own mother did not want him? Moreover, Kevin had spent seven years already in institutions, more than eight totally mute, and almost sixteen learning to feel comfortable being crazy. If that wasn’t the portrait of a loser, I didn’t know what would be.

I didn’t want this case. As it was, I already had too many children to become involved with one who would obviously be a black hole-a maw to dump time and energy and effort into with no return. And as I sat and listened and drew geometric designs on the blotter, I had an even more shameful thought. This was a private clinic; we usually didn’t get the welfare kids. All I had to do to get rid of this case was mention money in a very serious way. While Garson Gayer would obviously foot the bill for my initial work with Kevin Richter, if I didn’t want the case, well, that would be the easiest way.…

It was tempting. It was a good deal more tempting to refuse this case than I was ready to admit. Yet I couldn’t. I could think such thoughts but I couldn’t make myself act on them. It would have been so different in the schoolroom. Ed or Birk or Lew simply would have rung me from the Special Ed Office and told me, ‘I’ve got a new kid for you.’ And I would have groused because I always groused, and they wouldn’t have noticed because they never did. Then he’d be mine, that loser, that kid with no hope, who couldn’t make it anywhere else, and we’d try there in my room, amidst the battered books and the rummage-sale toys and noisy finches and the stink of unchanged pants, to build another chance. We didn’t succeed very often. Our triumphs, when they did come, were few and small. Sometimes no one else even noticed them. But it didn’t matter. I never thought of not trying, only because I never had the godly privilege of judging if I should. Or if I could. Or if I would. So, while not wanting this case, I took it and agreed to come. Given the option and seeing the odds, I sure wasn’t keen about it. But I did not think that should be my decision.

Because of my classroom experience and my research, I had evolved therapeutic techniques which varied a little from those of my colleagues at the clinic. I preferred to see the more seriously disturbed children daily over a shorter period of time, rather than once a week over many months or years. Also I often went to the child instead of having him come to the clinic, so that we could work in the troubled environment. In the initial sessions, I was very definite about setting up expectations for the child. From the beginning we both knew why I was there and what things we needed to accomplish together. On the other hand, the sessions themselves tended to be casual, unstructured affairs. This approach worked well for me and I was comfortable with it.

My research had yielded a reliable method for treating elective mutes. I set up the expectation that the child would speak, gave him the opportunity to do so and assumed he would. However, I was not sure what I could do for Kevin-under-the-table. While the technique had always worked before, I was concerned about its applicability to him. The most critical question, I thought, as I hung up from talking with the social worker, was whether or not Kevin was an elective mute. Had he ever really talked? To a worried or wishful parent, so many noises could sound like words. By my calculations, he would have been a very young child when anyone last actually heard him speak, and then it had only been his immediate family. Could a five-year-old sister be a trusted judge of speech? Could a mother assess the quality of her preschool son’s words, if she only occasionally heard him talk at home? And there was no evidence at all that anyone who might be considered a reliable judge of normal speech had ever heard him. Kevin wasn’t deaf; that had been checked repeatedly by the various institutions he had been in. He could gesture his basic needs but he did not know true sign language. Someone had tried to teach him at Garson Gayer, but a suspected very low IQ was cited when he didn’t learn. For all intents and purposes, Kevin was noncommunicative. Whether his silence was the result of choice or of circumstances or of disturbance or of some organic occurrence in the brain, no one knew.

So what could I do with him? How could I find out?

That first day in the therapy room had been vaguely reassuring to me. Despite his bizarre behaviors, he was aware enough of his environment to do something as canny as count the people leaving the room behind the mirror. That wasn’t a stupid boy’s actions, whatever his reported IQ. And yet he had let me in on the secret. When the others had left, he stopped rocking and responded to me.

Another thing I knew he could do was read. In fact, according to Kevin’s written schoolwork, he read startlingly well for a boy educated in institutions as if mentally retarded. He could comprehend a written text at a seventh-grade level.

Armed with these scanty bits of information, I decided to plow my way right in, assume he could talk and try to get him to. I settled on a tactic that had worked with other elective mutes: I’d have him read aloud to me from the book we’d started in the mirrored therapy room.

The next morning I returned to Garson Gayer. Gratefully, I accepted an alternative room down near the ward rather than go back to the room with the one-way mirror. The other therapists needed that room, Miss Wendolowski said, and I was quite glad not to have it. Kevin and I did not need the worry of ghosts along with everything else.

The room we got was a bare little affair. It was small. I could pace it in four steps either direction. The only furniture consisted of a table, two chairs and a bookcase with no books in it. There was a vomit-green carpet, the kind that wears like Astroturf. One wall was half windows, a nice feature. A broad radiator ran along the length below the windows and uttered a small reptilian sound. All other walls were bare and painted white, a not-quite-white white, gloss two-thirds of the way up for washability and the rest flat paint. That was an institutional painting habit and I hated it. I always felt as if I were in a discreet cage and, when a teacher, I’d felt obliged to hang the kids’ work up there on the flat part and get it mucky, just for the freedom of it. Here there were no pictures on the walls at all, no posters, nothing, save a black-and-white clock that audibly breathed the minutes. And the pale golden September sunshine.

I arrived before Kevin that morning. An aide escorted me down and then left to fetch him. I stood alone in the small room and waited. Beyond the windows I could see a little girl outside in the courtyard. She looked to be about eight or nine and was confined to a wheelchair. Her movements were spastic and her head lolled to one side. I could hear her crying for someone named Winnie. Over and over again she wailed, her voice high-pitched and keening. It was a lonely sound that made my skin crawl.

The door opened and the aide pushed Kevin in. Then, without entering himself, the aide asked me when we’d be through. Thirty minutes, I replied. He nodded, jangled his keys a moment and seemed ready to say something else. But he didn’t. Instead he closed the door and I heard the key turn in the lock. That startled me. I had no key of my own to let us out and I hadn’t expected to be locked in. A small twinge of panic pinched my stomach and I had to take a deep breath before I could accept the fact and turn to face Kevin.

He stood paralyzed with fear. His eyes darted frantically around the room. I was between him and the table and I could see him weighing the danger of passing me to get to safety.