Полная версия:

Muhammad Ali: A Tribute to the Greatest

BOOKS BY THOMAS HAUSER

GENERAL NON-FICTION

Missing

The Trial of Patrolman Thomas Shea

For Our Children (with Frank Macchiarola)

The Family Legal Companion

Final Warning: The Legacy of Chernobyl (with Dr Robert Gale)

Arnold Palmer: A Personal Journey

Confronting America’s Moral Crisis (with Frank Macchiarola)

Healing: A Journal of Tolerance and Understanding

With This Ring (with Frank Macchiarola)

A God to Hope For

Thomas Hauser on Sports

Reflections

BOXING NON-FICTION

The Black Lights: Inside the World of Professional Boxing

Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times

Muhammad Ali: Memories

Muhammad Ali: In Perspective

Muhammad Ali & Company

A Beautiful Sickness

A Year at the Fights

Brutal Artistry

The View from Ringside

Chaos, Corruption, Courage, and Glory

I Don’t Believe It, But It’s True

Knockout (with Vikki LaMotta)

The Greatest Sport of All

The Boxing Scene

An Unforgiving Sport

Boxing Is …

Box: The Face of Boxing

The Legend of Muhammad Ali (with Bart Barry)

Winks and Daggers

And the New …

Straight Writes and Jabs

Thomas Hauser on Boxing

A Hurting Sport

Muhammad Ali: A Tribute to the Greatest

FICTION

Ashworth & Palmer

Agatha’s Friends

The Beethoven Conspiracy

Hanneman’s War

The Fantasy

Dear Hannah

The Hawthorne Group

Mark Twain Remembers

Finding the Princess

Waiting for Carver Boyd

The Final Recollections of Charles Dickens

The Baker’s Tale

FOR CHILDREN

Martin Bear & Friends

COPYRIGHT

HarperSport

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Portions of this book were previously published as The Lost Legacy of Muhammad Ali (Sport Classic Books) and Muhammad Ali: The Lost Legacy (Robson Books)

First published by HarperSport 2016

FIRST EDITION

© Thomas Hauser 2016

Jacket layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

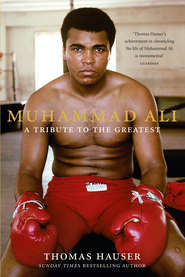

Front jacket shows Untitled, Miami, Florida, 1970.

Photograph by Gordon Parks. Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation.

A catalogue record of this book is

available from the British Library

Thomas Hauser asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780008152444

Ebook edition: June 2016 ISBN: 9780008152468

Version: 2016-06-04

EPIGRAPH

Muhammad Ali belongs to the world.

This book is dedicated to Muhammad

and to everyone who is part of his story.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Books by Thomas Hauser

Copyright

Epigraph

Author’s Note

PART I: ESSAYS

The Importance of Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali and Boxing

Muhammad Ali and Congress Remembered

The Athlete of the Century

Why Muhammad Ali Went to Iraq

The Olympic Flame

Ali as Diplomat: ‘No! No! No! Don’t!’

Ghosts of Manila

Rediscovering Joe Frazier through Dave Wolf’s Eyes

A Holiday Season Fantasy

Muhammad Ali: A Classic Hero

Elvis and Ali

PART II: PERSONAL MEMORIES

The Day I Met Muhammad Ali

I Was at Ali–Frazier I

Reflections on Time Spent with Muhammad Ali

‘I’m Coming Back to Whup Mike Tyson’s Butt’

Muhammad Ali at Notre Dame: A Night to Remember

Muhammad Ali: Thanksgiving 1996 – ‘I’ve Got a Lot to Be Thankful For’

Pensacola, Florida: 27 February 1997

A Day of Remembrance

Remembering Joe Frazier

‘Did Barbra Streisand Whup Sonny Liston?’

PART III: A LIFE IN QUOTES

PART IV: LEGACY

The Lost Legacy of Muhammad Ali

The Long Sad Goodbye

Muhammad Ali’s Ring Record

About the Publisher

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times, which was published in 1991, is often referred to as the definitive account of the first fifty years of Ali’s life. This is the companion volume to that book. An earlier version was published in the United Kingdom in 2005 under the title Muhammad Ali: The Lost Legacy. At that time, it contained all of the essays and articles I’d written about Ali. Muhammad Ali: A Tribute to the Greatest contains recently authored pieces, including the previously unpublished essay, ‘The Long Sad Goodbye’.

Thomas Hauser

PART I

THE IMPORTANCE OF MUHAMMAD ALI

(1996)

Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr, as Muhammad Ali was once known, was born in Louisville, Kentucky, on 17 January 1942. Louisville was a city with segregated public facilities; noted for the Kentucky Derby, mint juleps, and other reminders of southern aristocracy. Blacks were the servant class in Louisville. They raked manure in the backstretch at Churchill Downs and cleaned other people’s homes. Growing up in Louisville, the best on the socio-economic ladder that most black people could realistically hope for was to become a clergyman or a teacher at an all-black school. In a society where it was often felt that might makes right, ‘white’ was synonymous with both.

Ali’s father, Cassius Marcellus Clay Sr, supported a wife and two sons by painting billboards and signs. Ali’s mother, Odessa Grady Clay, worked on occasion as a household domestic. ‘I remember one time when Cassius was small,’ Mrs Clay later recalled. ‘We were downtown at a five-and-ten-cents store. He wanted a drink of water, and they wouldn’t give him one because of his colour. And that really affected him. He didn’t like that at all, being a child and thirsty. He started crying, and I said, “Come on; I’ll take you someplace and get you some water.” But it really hurt him.’

When Cassius Clay was 12 years old, his bike was stolen. That led him to take up boxing under the tutelage of a Louisville policeman named Joe Martin. Clay advanced through the amateur ranks, won a gold medal at the 1960 Olympics in Rome, and turned pro under the guidance of The Louisville Sponsoring Group, a syndicate comprised of 11 wealthy white men.

‘Cassius was something in those days,’ his long-time physician, Ferdie Pacheco, remembers. ‘He began training in Miami with Angelo Dundee, and Angelo put him in a den of iniquity called the Mary Elizabeth Hotel, because Angelo is one of the most innocent men in the world and it was a cheap hotel. This place was full of pimps, thieves and drug dealers. And here’s Cassius, who comes from a good home, and all of a sudden he’s involved with this circus of street people. At first, the hustlers thought he was just another guy to take to the cleaners; another guy to steal from; another guy to sell dope to; another guy to fix up with a girl. He had this incredible innocence about him, and usually that kind of person gets eaten alive in the ghetto. But then the hustlers all fell in love with him, like everybody does, and they started to feel protective of him. If someone tried to sell him a girl, the others would say, “Leave him alone; he’s not into that.” If a guy came around, saying, “Have a drink,” it was, “Shut up; he’s in training.” But that’s the story of Ali’s life. He’s always been like a little kid, climbing out onto tree limbs, sawing them off behind him and coming out okay.’

In the early stages of his professional career, Cassius Clay was more highly regarded for his charm and personality than for his ring skills. He told the world that he was ‘The Greatest’, but the brutal realities of boxing seemed to dictate otherwise. Then, on 25 February 1964, in one of the most stunning upsets in sports history, Clay knocked out Sonny Liston to become heavyweight champion of the world. Two days later, he shocked the world again by announcing that he had accepted the teachings of a black separatist religion known as the Nation of Islam. And on 6 March 1964, he took the name ‘Muhammad Ali’, which was given to him by his spiritual mentor, Elijah Muhammad.

For the next three years, Ali dominated boxing as thoroughly and magnificently as any fighter ever. But outside the ring, his persona was being sculpted in ways that were even more important. ‘My first impression of Cassius Clay,’ author Alex Haley later recalled, ‘was of someone with an incredibly versatile personality. You never knew quite where he was in psychic posture. He was almost like that shell game, with a pea and three shells. You know: which shell is the pea under? But he had a belief in himself and convictions far stronger than anybody dreamed he would.’

As the 1960s grew more tumultuous, Ali became a lightning rod for dissent in America. His message of black pride and black resistance to white domination was on the cutting edge of the era. Not everything he preached was wise, and Ali himself now rejects some of the beliefs that he adhered to then. Indeed, one might find an allegory for his life in a remark he once made to fellow Olympian Ralph Boston. ‘I played golf,’ Ali reported, ‘and I hit the thing long, but I never knew where it was going.’

Sometimes, though, Ali knew precisely where he was going. On 28 April 1967, citing his religious beliefs, he refused induction into the United States Army at the height of the war in Vietnam. Ali’s refusal followed a blunt statement, voiced 14 months earlier – ‘I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong.’ And the American establishment responded with a vengeance, demanding, ‘Since when did war become a matter of personal quarrels? War is duty. Your country calls – you answer.’

On 20 June 1967, Ali was convicted of refusing induction into the United States Armed Forces and sentenced to five years in prison. Four years later, his conviction was unanimously overturned by the United States Supreme Court. But in the interim, he was stripped of his title and precluded from fighting for three and a half years. ‘He did not believe he would ever fight again,’ Ali’s wife at that time, Belinda Ali, said of her husband’s ‘exile’ from boxing. ‘He wanted to, but he truly believed that he would never fight again.’

Meanwhile, Ali’s impact was growing – among black Americans, among those who opposed the war in Vietnam, among all people with grievances against The System. ‘It’s hard to imagine that a sports figure could have so much political influence on so many people,’ observes Julian Bond. And Jerry Izenberg of the Newark Star-Ledger recalls the scene in October 1970, when at long last Ali was allowed to return to the ring.

‘About two days before the fight against Jerry Quarry, it became clear to me that something had changed,’ Izenberg remembers. ‘Long lines of people were checking into the hotel. They were dressed differently than the people who used to go to fights. I saw men wearing capes and hats with plumes, and women wearing next to nothing at all. Limousines were lined up at the curb. Money was being flashed everywhere. And I was confused, until a friend of mine who was black said to me, “You don’t get it. Don’t you understand? This is the heavyweight champion who beat The Man. The Man said he would never fight again, and here he is, fighting in Atlanta, Georgia.”’

Four months later, Ali’s comeback was temporarily derailed when he lost to Joe Frazier. It was a fight of truly historic proportions. Nobody in America was neutral that night. ‘It does me good to lose about once every ten years,’ Ali jested after the bout. But physically and psychologically, his pain was enormous. Subsequently, Ali avenged his loss to Frazier twice in historic bouts. Ultimately, he won the heavyweight championship of the world an unprecedented three times.

Meanwhile, Ali’s religious views were evolving. In the mid-1970s, he began studying the Qur’an more seriously, focusing on Orthodox Islam. His earlier adherence to the teachings of Elijah Muhammad – that white people are ‘devils’ and there is no heaven or hell – was replaced by a spiritual embrace of all people and preparation for his own afterlife. In 1984, Ali spoke out publicly against the separatist doctrine of Louis Farrakhan, declaring, ‘What he teaches is not at all what we believe in. He represents the time of our struggle in the dark and a time of confusion in us, and we don’t want to be associated with that at all.’

Ali today is a deeply religious man. Although his health is not what it once was, his thought processes remain clear. He is, still, the most recognisable and the most loved person in the world.

But is Muhammad Ali relevant today? In an age when self-dealing and greed have become public policy, does a 54-year-old man who suffers from Parkinson’s syndrome really matter? At a time when an intrusive worldwide electronic media dominates, and celebrity status and fame are mistaken for heroism, is true heroism possible?

In response to these questions, it should first be noted that, unlike many famous people, Ali is not a creation of the media. He used the media in an extraordinary fashion. And certainly, he came along at the right time in terms of television. In 1960, when Cassius Clay won an Olympic gold medal, TV was crawling out of its infancy. The television networks had just learned how to focus cameras on people, build them up, and follow stories through to the end. And Ali loved that. As Jerry Izenberg later observed, ‘Once Ali found out about television, it was, “Where? Bring the cameras! I’m ready now.”’

Still, Ali’s fame is pure. Athletes today are known as much for their endorsement contracts and salaries as for their competitive performances. Fame now often stems from sports marketing rather than the other way around. Bo Jackson was briefly one of the most famous men in America because of his Nike shoe commercials. Michael Jordan and virtually all of his brethren derive a substantial portion of their visibility from commercial endeavours. Yet, as great an athlete as Michael Jordan is, he doesn’t have the ability to move people’s hearts and minds the way that Ali has moved them for decades. And what Muhammad Ali means to the world can be viewed from an ever deepening perspective today.

Ali entered the public arena as an athlete. To many, that’s significant.

‘Sports is a major factor in ideological control,’ says sociologist Noam Chomsky. ‘After all, people have minds; they’ve got to be involved in something; and it’s important to make sure they’re involved in things that have absolutely no significance. So professional sports is perfect. It instils the right ideas of passivity. It’s a way of keeping people diverted from issues like who runs society and who makes the decisions on how their lives are to be led.’

But Ali broke the mould. When he appeared on the scene, it was popular among those in the vanguard of the civil rights movement to take the ‘safe’ path. That path wasn’t safe for those who participated in the struggle. Martin Luther King Jr, Medgar Evers, Viola Liuzzo, and other courageous men and women were subjected to economic assaults, violence and death when they carried the struggle ‘too far’. But the road they travelled was designed to be as non-threatening as possible for white America. White Americans were told, ‘All that black people want is what you want for yourselves. We’re appealing to your conscience.’

Then along came Ali, preaching not ‘white American values’, but freedom and equality of a kind rarely seen anywhere in the world. And as if that wasn’t threatening enough, Ali attacked the status quo from outside politics and outside the accepted strategies of the civil rights movement.

‘I remember when Ali joined the Nation of Islam,’ Julian Bond recalls. ‘The act of joining was not something many of us particularly liked. But the notion he’d do it; that he’d jump out there, join this group that was so despised by mainstream America, and be proud of it, sent a little thrill through you.’

‘The nature of the controversy,’ football great Jim Brown (also the founder of the Black Economic Union) said later, ‘was that white folks could not stand free black folks. White America could not stand to think that a sports hero that it was allowing to make big dollars would embrace something like the Nation of Islam. But this young man had the courage to stand up like no one else and risk, not only his life, but everything else that he had.’

Ali himself down-played his role. ‘I’m not no leader. I’m a little humble follower,’ he said in 1964. But to many, he was the ultimate symbol of black pride and black resistance to an unjust social order.

Sometimes Ali spoke with humour. ‘I’m not just saying black is best because I’m black,’ he told a college audience during his exile from boxing. ‘I can prove it. If you want some rich dirt, you look for the black dirt. If you want the best bread, you want the whole wheat rye bread. Costs more money, but it’s better for your digestive system. You want the best sugar for cooking; it’s the brown sugar. The blacker the berry, the sweeter the fruit. If I want a strong cup of coffee, I’ll take it black. The coffee gets weak if I integrate it with white cream.’

Other times, Ali’s remarks were less humorous and more barbed. But for millions of people, the experience of being black changed because of Muhammad Ali. Listen to the voices of some who heard his call:

Bryant Gumbel: One of the reasons the civil rights movement went forward was that black people were able to overcome their fear. And I honestly believe that, for many black Americans, that came from watching Muhammad Ali. He simply refused to be afraid. And being that way, he gave other people courage.

Alex Haley: We are not white, you know. And it’s not an anti-white thing to be proud to be us and to want someone to champion. And Muhammad Ali was the absolute ultimate champion.

Arthur Ashe: Ali didn’t just change the image that African-Americans have of themselves. He opened the eyes of a lot of white people to the potential of African-Americans; who we are and what we can be.

Abraham Lincoln once said that he regarded the Emancipation Proclamation as the central act of his administration. ‘It is a momentous thing,’ Lincoln wrote, ‘to be the instrument under Providence of the liberation of a race.’

Muhammad Ali was such an instrument. As commentator Gil Noble later explained, ‘Everybody was plugged into this man, because he was taking on America. There had never been anybody in his position who directly addressed himself to racism. Racism was virulent, but you didn’t talk about those things. If you wanted to make it in this country, you had to be quiet, carry yourself in a certain way and not say anything about what was going on, even though there was a knife sticking in your chest. Ali changed all of that. He just laid it out and talked about racism and slavery and all of that stuff. He put it on the table. And everybody who was black, whether they said it overtly or covertly, said “Amen.”’

But Ali’s appeal would come to extend far beyond black America. When he refused induction into the United States Army, he stood up to armies everywhere in support of the proposition that, ‘Unless you have a very good reason to kill, war is wrong.’

‘I don’t think Ali was aware of the impact that his not going in the army would have on other people,’ says his long-time friend, Howard Bingham. ‘Ali was just doing what he thought was right for him. He had no idea at the time that this was going to affect how people all over the United States would react to the war and the draft.’

Many Americans vehemently condemned Ali’s stand. It came at a time when most people in the United States still supported the war. But as Julian Bond later observed, ‘When Ali refused to take the symbolic step forward, everybody knew about it moments later. You could hear people talking about it on street corners. It was on everyone’s lips.’

‘The government didn’t need Ali to fight the war,’ Ramsey Clark, then the Attorney General of the United States, recalls. ‘But they would have loved to put him in the service; get his picture in there; maybe give him a couple of stripes on his sleeve, and take him all over the world. Think of the power that would have had in Africa, Asia and South America. Here’s this proud American serviceman, fighting symbolically for his country. They would have loved to do that.’

But instead, what the government got was a reaffirmation of Ali’s earlier statement – ‘I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong.’

‘And that rang serious alarm bells,’ says Noam Chomsky, ‘because it raised the question of why poor people in the United States were being forced by rich people in the United States to kill poor people in Vietnam. Putting it simply, that’s what it amounted to. And Ali put it very simply in ways that people could understand.’

Ali’s refusal to accept induction placed him once and for all at the vortex of the 1960s. ‘You had riots in the streets; you had assassinations; you had the war in Vietnam,’ Dave Kindred of the Atlanta Constitution remembers. ‘It was a violent, turbulent, almost indecipherable time in America, and Ali was in all of those fires at once in addition to being heavyweight champion of the world.’

That championship was soon taken from Ali, but he never wavered from his cause. Speaking to a college audience, he proclaimed, ‘I would like to say to those of you who think I’ve lost so much, I have gained everything. I have peace of heart; I have a clear, free conscience. And I’m proud. I wake up happy. I go to bed happy. And if I go to jail, I’ll go to jail happy. Boys go to war and die for what they believe, so I don’t see why the world is so shook up over me suffering for what I believe. What’s so unusual about that?’

‘It really impressed me that Ali gave up his title,’ says former heavyweight champion Larry Holmes, who understands Ali’s sacrifice as well as anyone. ‘Once you have it, you never want to lose it; because once you lose it, it’s hard to get it back.’

But by the late 1960s, Ali was more than heavyweight champion. That had become almost a side issue. He was a living embodiment of the proposition that principles matter. And the most powerful thing about him was no longer his fists; it was his conscience and the composure with which he carried himself: