Полная версия:

Leonardo and the Death Machine

Leonardo and the Death Machine

Robert J. Harris

For Debby, who gave me my wings.

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Dedication

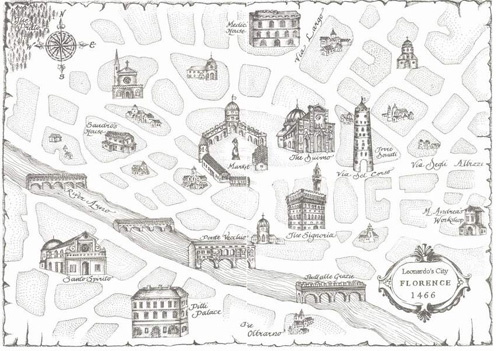

Maps

1 FISHBONES AND FIRE

2 THE DEBT COLLECTOR

3 THE INFERNAL DEVICE

4 THE LION OF ANCHIANO

5 A BIRD IN FLIGHT

6 THE GIRL IN THE TOWER

7 A WELL-BUILT PRISON

8 THE HONOUR OF THIEVES

9 THE HAND OF GOD

10 THE OUTCASTS OF HEAVEN

11 THE HOMECOMING

12 THE PRODIGAL SON

13 THE BRAWLER

14 DAGGER’S POINT

15 COGS AND WHEELS

16 THE DOOR TO THE UNIVERSE

17 THE SECRET OF THE EGG

18 BENEATH THE DOME

19 DISCOVERY AND DANGER

20 A MAN OF INFLUENCE

21 A NEST OF VIPERS

22 A CHOICE OF ANGELS

23 THE UNHOLY MOUNTAIN

24 INTO THE DARKNESS

25 THE PIT

26 THE MACHINERY OF DEATH

27 THE AGE OF WONDERS

Afterword

Also by the Same Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Maps

1 FISHBONES AND FIRE

“One – two – three,” Leonardo muttered, counting each stroke of the mallet. The third hit drove the nail flat into the wood, fixing another stretch of canvas on to the frame.

Only two more nails to go. “One” – thud – “two” – thud – “three” – thud.

There were twenty nails in all and at least three knocks were required to bash each one in. If he didn’t hit the nail just right, it would bend in half. When that happened, the bent nail had to be worked loose and tossed away so that a new one could be hammered in its place.

“Make sure you knock those nails in straight, country boy, otherwise you’ll tear the canvas,” warned Nicolo. He was finishing a painting of a laughing woman, using a bust made by their master as a model. At seventeen he was the senior apprentice in the workshop. The master, Andrea del Verrocchio, was away at a meeting with the members of the Signoria, the ruling council of Florence, leaving Nicolo in charge.

“No need to worry about that,” said Leonardo. “This is the last one.”

Mentally, he painted the older boy’s face in miniature on the head of the final nail and brought the mallet down with a vengeful whack. Leonardo stared in amazement at the result and grinned. For the first time he had driven the nail right into the wood with a single blow. He would have to remember that trick.

He stood up to admire his handiwork and caught a whiff of rotten fish. The smell stung his nostrils and made his stomach lurch.

“Horrible, isn’t it?” said skinny little Gabriello. He was stirring fishbones around in an iron pot over a raised brick fire pit. This melted them into a paste that was spread over the canvas before any paint was applied.

“Still, it could be worse,” the little apprentice added. “We could be using calf hooves again and they really stink.”

“Some things smell even worse than that,” said Leonardo with a sidelong glance at Nicolo.

Gabriello chuckled, then coughed as the fishy fumes got into his throat. The senior apprentice did not notice the insult. He was too busy painting the last few locks of the woman’s hair, his tongue stuck into his cheek in concentration.

Leonardo lifted the frame up off the straw-covered floor and leaned it carefully against one of the worktables. He nodded in satisfaction. The frame was firmly constructed, the canvas straight and taut. When Maestro Andrea came to inspect it, he would be pleased.

A gust of wind from the open window sent a puff of acrid dust up his nose. Leonardo turned away quickly so that his sneeze missed the canvas, then waved his hands about to clear the air.

The dust came from the corner of the room where Vanni and Giorgio were standing over a slab of porphyry, grinding brightly coloured minerals with their mortars. This produced a fine powder which would be mixed with egg to make paints. They were chatting together and occasionally breaking into song, their voices rising raucously above the rumble of passing carts and the yells of pedlars hawking their wares in the street outside.

“Pipe down and pay attention to what you’re doing!” Nicolo barked at them. “You’re spreading that dust all over the room.”

Leonardo pulled out his kerchief and blew his nose. He had thought that when his father brought him to Florence to be a pupil in the workshop of a great artist, he would be leaving behind the dirt and stench of the farmyard. But there was just as much dirt here and the stench was even worse. When Maestro Andrea was sculpting a statue, the dust hung so thick in the air it was like a chalky fog. And always there was the stink of fishbones, eggs, charcoal, turpentine and all the other unglamorous materials of the artist’s trade.

Tucking his kerchief back into his sleeve, Leonardo went to the corner where his own paintings and sketches were stored. Reaching into the midst of them, he pulled out his latest work, one which Maestro Andrea had not assigned him. As he examined the object, Nicolo’s voice boomed out behind him.

“There! It is done!”

From his grandiose tone you would have thought he had just fitted the last brick into the great dome of the cathedral instead of completing a routine exercise.

Nicolo beckoned Vanni and Giorgio over to admire his ‘masterpiece’. They gladly left their grinding materials behind and hurried over to examine the canvas, brushing the mineral dust from their aprons.

“It’s very good, Nicolo,” said Vanni, knowing exactly what he was supposed to say.

“Yes, it’s very good,” Giorgio echoed automatically.

Leonardo strolled over and eyed the finished picture. All the life and animation of Maestro Andrea’s sculpture had been lost in Nicolo’s painting. It was as if he had strained the meat and vegetables out of a rich stew and reduced it to a thin, unappetising gruel.

“So what do you think, Leonardo da Vinci?” Nicolo asked. The stern challenge in his voice made it clear exactly how Leonardo was supposed to answer. But Leonardo had taken enough insults from Nicolo that he wasn’t going to let slip this chance to hit back.

“I think that if a corpse ever wants its portrait painted, you’ll be the man for the job,” he replied. Gabriello slapped a hand over his mouth to stifle a laugh. Nicolo growled and raised his fist.

Leonardo took a step back but did not flinch. He was three years younger than the senior apprentice but equal in both height and strength. If Nicolo wanted a fight, he was ready – and eager – to oblige. But Maestro Andrea had made it clear that anyone caught fighting in the workshop would immediately find himself out on the street without a denaro to his name.

The same thought was evidently in Nicolo’s mind. He lowered his fist, though his face was still ruddy with anger. “You may dress up like the son of a rich man,” he sneered, “but you still have the taste of a farm boy.”

Leonardo winced. He was proud of the blue velvet tunic and scarlet hose he wore under his apron, even though he knew some of the other apprentices sniggered at his finery.

“At least I have some taste,” he retorted. He waved at the painting. “This isn’t art. This is murder.”

Nicolo’s eyes flashed with rage. “It is more than a clumsy left-hander like you could ever do!” Then he spotted what was in Leonardo’s hand and snatched the wooden object from the younger boy’s grasp. “What’s this? Some sort of toy?”

“Give that back!” cried Leonardo hotly. He made a grab that Nicolo easily avoided. The senior apprentice waved his prize in the air so that everyone could see it.

It was a wooden cylinder, small enough to fit into a man’s hand, with a piece of cord dangling from a hole in the side. There was another hole in the top into which a wooden spindle had been fitted. From the end of the spindle, four thin wooden blades spread out in different directions like the petals of a flower.

“Is that what you’ve been doing in that corner all this time?” asked Vanni.

“It looks like a little windmill,” said Giorgio, “except the vanes are on top instead of on the side.”

“Is that what it is, country boy?” Nicolo asked. “A toy windmill to remind you of life on the farm?”

“No, not at all,” said Leonardo, so annoyed he could hardly speak.

“Maybe it’s a baby’s rattle.” Nicolo shook the wooden device by his ear, but it made no sound. Leonardo was tempted to make another grab but he was afraid of damaging his creation.

“I give up, Leonardo,” smirked Nicolo. “What does it do?”

Leonardo glared at him. “It flies.”

“Flies?” The answer was so incredible it wiped the sneer from Nicolo’s face.

“A merchant from Padua was selling one like it in the market,” Leonardo explained. “He said it came from Cathay and he wanted five florins for it.”

Vanni let out a low whistle. It was a sum beyond the imagination of apprentices like themselves.

“But for a few denari he let me examine it to see how it worked.”

“And then you made your own,” said Gabriello admiringly.

“Yes, I finished carving the four blades last night.”

“And you think it will fly?” snorted Nicolo. “You’ve gone mad, country boy. The smell of turps has rotted your brain.”

“Here, I’ll show you,” Leonardo offered, reaching for the device.

Nicolo yanked it out of reach. “Not so fast,” he said. “We have to make sure there’s no trickery here. How does it work?”

Leonardo gritted his teeth and reined in his temper. Ever since he had arrived at the workshop three months before, Nicolo had been goading him, mimicking the country accent he had been working so hard to erase, sneering at his drawings and telling him his hands were better suited to the plough than the brush and palette.

“There’s a screw inside and the stick with the vanes on top is fitted into that,” Leonardo explained slowly and carefully. “When you pull the string, the screw turns and sets the vanes spinning.”

“That’s it?” Nicolo asked.

Leonardo nodded. Grinning, Nicolo took a tight grip on the cord and prepared to pull.

“No, let me do it!” yelled Leonardo.

It was too late. Nicolo jerked his elbow back so hard the string snapped off. No one noticed that. What they noticed was the flying. Its blades a spinning blur, the spindle shot into the air, drawing gasps of astonishment from the apprentices.

“It’s sorcery!” Gabriello squeaked as the flying device came twirling towards him. It hovered for a second over the metal grille of the fire pit. Then – to Leonardo’s horror – it dropped.

Gabriello leapt away with a squeal of panic. Leonardo lunged for the device as it fell between the bars of the grille.

Too late again. There was a clang and a crash and a screech from Vanni.

Leonardo had knocked the gooey mess of bubbling fishbones on to the fire. Gobs of it ignited and burst into the air like shooting stars. They rained down on the floor and in an instant the straw covering burst into flames.

Gabriello and the other apprentices stampeded for the door.

“You stupid bumpkin!” Nicolo howled at Leonardo. “You’ve set the house on fire!”

2 THE DEBT COLLECTOR

Leonardo clenched his fists and fought down his panic. What was he to do? In a few moments the fire could spread out of control. The only firefighters in the city were some volunteers from the stonemasons’ guild, but there was no time to summon them.

Then he remembered how his Uncle Francesco had stopped a fire that sprang up in the barn when one of the cows kicked over a lantern. Looking quickly around, he snatched the dust covering from one of Maestro Andrea’s paintings. He hurled it over the fire and flung his own body on top of it to smother the flames.

He could feel the heat beneath him and smell the charred straw. Leonardo screwed his eyes tight shut and he held his breath, half expecting to be incinerated. That was still preferable to the humiliation of seeing the workshop destroyed through his clumsiness.

An excited babble of voices prompted him to open his eyes. Gabriello was leaning over him. “I think the fire’s out,” he said.

The other apprentices gathered around, nervously giggling and elbowing each other. Their faces were still white with shock. Leonardo propped himself up on one elbow, looking around for Nicolo.

“You saw, didn’t you?” he challenged. “You saw it fly.”

“I saw a stick jump into the air and fall into the fire,” Nicolo replied. He shook his head. “Not very impressive.”

Nicolo still had the other part of the flying device in his hand and now he flung it away contemptuously. It clattered across the floor and rolled out of sight under a table.

A rage hotter than any fire welled up inside Leonardo’s breast. He would knock that smirk off Nicolo’s face, no matter what the consequences.

He jumped to his feet. But before he could swing a punch, the door banged open.

Maestro Andrea del Verrocchio marched in, a dozen rolls of parchment tucked under one arm and a heavy leather satchel slung over the other. He strode briskly across the room towards his study without even looking at his apprentices.

“Leonardo da Vinci!” he called as he vanished through the doorway.

Leonardo started guiltily. “Yes, Maestro?”

“Fetch me a pitcher of water! The rest of you, this is not a holy day. Get back to work!”

Nicolo snatched the scorched covering off the floor and stuffed it away out of sight under a workbench. Vanni and Giorgio gathered up the burnt straw and pitched it out of the window. Gabriello darted off to prepare a fresh pot of fishbones.

Leonardo rushed out of the back door to the pump and filled a pitcher with fresh water. When he got to the study, Maestro Andrea had laid down his scrolls and satchel and was studying some letters. Leonardo poured a cup of water and handed it to him.

“Don’t leave,” the maestro said as he lifted the cup to his lips. “I have something else for you to do.”

As Maestro Andrea drank, Leonardo looked around at the drawings that littered the tables and the walls, studies of saints and angels, soldiers and animals.

With his round, pleasant face and stout belly, Andrea looked like a prosperous baker. In fact, he was one of the most brilliant and successful artists in Florence. He was so busy that he sometimes had to bring in other artists as his assistants. Recalling this, Leonardo had the exciting thought that perhaps the master was going to ask for his help in completing a major work.

Andrea gulped down the last of the water and smacked his thick lips. “Arguing terms with the members of the Signoria is thirsty work,” he said. “Still, if our government want a new statue of St. Thomas for their chapel they will have to pay a decent price.”

Leonardo tried to sound businesslike too. “I finished stretching the canvas, Maestro,” he reported.

“I saw that when I came in,” said Andrea, “just as I saw the overturned pot and the burnt straw and smelled the charred fishbones.”

Leonardo was astonished. He could have sworn the master had not so much as glanced their way before entering his study. “There was an accident,” he began apologetically.

Andrea raised a hand to silence him. “You are young men with high spirits and you will have your misadventures. As long as no one was hurt, there is no more to say.”

“You said you had something for me to do,” Leonardo reminded him.

“Yes, here it is,” said Andrea. He presented the boy with a folded sheet of parchment sealed with a blob of wax.

“What’s this?” Leonardo asked eagerly. “A sketch of the new work you’ve been commissioned to do? Would you like me to do the preliminary outlines?”

Maestro Andrea shook his head. “It’s a bill for fourteen florins,” he stated flatly.

“A bill?” Leonardo’s heart plummeted. “Maestro, don’t make me a debt collector. I came here to be an artist.”

“Money is the lifeblood of art, Leonardo. If you haven’t learned that by now you should go back to your father and be a notary like him.”

The suggestion stung Leonardo like a hot needle. “No, I don’t want to be like him. But I hoped…”

“You hoped what?” Andrea asked.

Leonardo raised his head to meet his master’s eye. This was no time to be nervous and awkward. That would not earn his respect.

“I hoped you would have a proper piece of art for me to do, not a practice painting on used canvas or a wax model.”

“What? Have you aged ten years overnight? Have the talents of the masters seeped into your soul while you slept? To become an artist takes years and you have been here for only a few months.”

“You do not become an artist by running errands, Maestro,” Leonardo persisted.

Andrea peered down his snub nose at the boy. “I have told all of you many times that an artist begins his work by seeing and completes it by understanding. What are you going to see sitting around here? I’m giving you the chance to go out and find some inspiration. Now take this note to Maestro Silvestro’s workshop.”

“The one who borrowed that bronze from you last month?”

“The very same,” Maestro Andrea confirmed. “He still hasn’t replaced it, so I’ll have the money instead.”

“But it’s in the Oltrarno,” Leonardo complained, wrinkling his nose. This was the name given to the area of the city on the southern side of the River Arno. It was still more village than city and was notorious for its floods and outbreaks of plague.

“Very true,” Andrea agreed dryly. “I am sure your beautiful clothes will bring a welcome dash of colour into the lives of the unhappy people who live there.”

Leonardo straightened his tunic and flicked a spot of ash from his sleeve. “All the young gentlemen of Florence are dressing like this,” he said defensively.

“All the rich young gentlemen of Florence,” Maestro Andrea corrected him.

“There’s nothing wrong with making a good impression.”

“You are quite correct,” said Andrea, waving him away dismissively. “Now go and make a good impression on Maestro Silvestro.”

Leonardo returned to the workshop, taking off his smock as he headed for the door.

“Where are you going?” Nicolo demanded.

“I have an important commission from Maestro Andrea,” Leonardo answered haughtily. “He wants me to exercise my eyes and my understanding.”

Escaping from the workshop, Leonardo strode off down the Via dell’Agnolo, muttering resentfully to himself. After all his hard work his flying device was ruined, and now he was reduced to collecting debts. He very much doubted he would see anything to inspire him today.

In this year of 1466, Florence was the centre of trade and banking for all of Europe, and the bustle in the narrow streets bore witness to the city’s importance. Wagons and carriages jostled alongside workers hurrying to and from the foundries and textile factories. Buildings rose up to three storeys high, with balconies jutting out of the top floors. Neighbours on opposite sides of the street could almost reach across and shake hands with each other.

As he approached the River Arno, Leonardo saw the flatboats heading downstream, carrying off their bolts of brightly coloured Florentine cloth to be transported to Spain, France, England and Germany. Other boats were bringing their cargo of untreated wool into the city to be washed, combed and dyed in the factories.

The city’s oldest bridge, the Ponte Vecchio, loomed ahead, its honey-coloured stonework bathed in the glow of the hot August sunshine. Both sides of the bridge were lined with the shops of butchers, leatherworkers and blacksmiths. As Leonardo crossed over, a blacksmith tipped a bucket of ashes into the river, provoking a volley of curses from the boatmen passing below.

As soon as he entered the Oltrarno, Leonardo was reminded of his home village of Anchiano, many miles to the north. Washing was strung between the trees, chickens scratched at the doorsteps, and everywhere there was the smell of garlic and baking bread.

In stark contrast to the humble cottages was the huge stone palace Leonardo could see rearing up like a cliff face in the middle of the Oltrarno, with workers swarming all over its scaffolding. He knew from the gossip of his fellow apprentices that it belonged to Luca Pitti, an ageing politician who liked to think of himself as Florence’s leading citizen. Even though the real power in the city lay in the hands of the Medici family, Pitti was determined to prove that he was every bit their equal, even if he went bankrupt in the process.

Leonardo turned right, away from the palace and towards the church of Santo Spirito. Silvestro’s workshop was in one of the alleys behind the church, but Leonardo wasn’t sure which one. He paused to sniff the air and immediately caught the pungent scent of cow dung, burnt ox-horn, and wet clay, all of which were used in the casting of bronze statues.

Following his nose he soon arrived at the shabby workshop of Silvestro. The shutters hung drunkenly from the windows and there were several tiles missing from the roof. Acrid smoke streamed from Silvestro’s furnace and hung in a sullen, black cloud over the street. Finding the door ajar, Leonardo pushed it open and stepped inside.

A pair of surly apprentices in stained, threadbare smocks looked up as he entered. They were mixing up a supply of casting wax. One had a face covered in pimples while the other was twitching as though his clothes were filled with lice.

Proud of his own finery, Leonardo drew himself up in a dignified fashion and inquired, “Is Maestro Silvestro at home?”

The two apprentices turned to each other with dull, expressionless eyes. Leonardo was reminded of a pair of oxen in a field.

“He’s in his private studio,” grunted Pimple-face.

“And where would that be?” asked Leonardo.

The Twitcher tilted his head to indicate a stout door at the far end of the workshop.

With a curt nod of thanks, Leonardo moved on. Behind him he heard one of them mutter, “He must think he’s an envoy from the Pope.” The other apprentice sniggered.

Leonardo ignored them and cast his eyes over the room. The shelves along the wall held only a few jars of pigment and these were thickly caked with dust. Discarded bristles and splinters of wood littered the rush-covered floor.

As he raised his fist to rap on Silvestro’s door, Leonardo was brought up short by a sudden outburst of angry voices from the room beyond. They were as furious as a couple of dogs fighting over a bone. Even muffled by the door their words were clearly audible.

“Today! You said today!” snarled the first voice, rough as sandstone.

“I said the components would be complete by today,” the second voice boomed like a gusty wind. “I never said the construction would be complete, never!”

“I think you know what happens to men who cross me,” rasped the first man.

“Save your threats for those you are paid to terrorise,” the second man said. “All will be ready on schedule.” Leonardo could hear the weakness underlying his confident words.