скачать книгу бесплатно

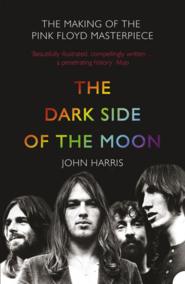

The Dark Side of the Moon: The Making of the Pink Floyd Masterpiece

John Harris

A behind-the-scenes, in-depth look at the making of one of the greatest sonic masterpieces and most commercially successful albums of all time.Over three decades after its release, Pink Floyd’s ‘The Dark Side of the Moon’ remains one of the most acclaimed albums of all time. Its sales total around 30 million copies worldwide. In its first run, it took up residence in the US charts for a mind-boggling 724 weeks. According to recent estimates, one in five British households owns a copy.This, however, is only a fraction of the story. ‘Dark Side’ is rock’s most fully realised and elegant concept album, based on themes of madness, anxiety and alienation that were rooted in the band’s history – and particularly in the tragic tale of their one – time leader Syd Barrett.Drawing on original interviews with bass guitarist and chief songwriter Roger Waters, guitarist David Gilmour, and the album’s supporting cast ,‘The Dark Side of the Moon’ is a must-have for the millions of devoted fans who desire to know more about one of the most timeless, compelling, commercially successful, and mysterious albums ever made.

JOHN HARRIS

THE DARK SIDE OF THE MOON

THE MAKING OF THE PINK FLOYD MASTERPIECE

Copyright (#ub83159fc-50d4-5db5-822f-ccd753fc943d)

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

This edition published by Harper Perennial 2006

First published in Great Britain in 2005 by Fourth Estate

Copyright © John Harris 2005

John Harris asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780007232291

Ebook Edition © NOVEMBER 2012 ISBN 9780007383412

Version: 2016-03-18

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Contents

Cover (#uc9632f8d-41ec-5d58-b9af-ed7c69837fbb)

Title Page (#u890ffa30-01a7-5bda-86e4-a225986bdda8)

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue January 2003

CHAPTER 1 The Lunatic Is in My Head: Syd Barrett and the Origins of Pink Floyd

CHAPTER 2 Hanging On in Quiet Desperation: Roger Waters and Pink Floyd Mark II

CHAPTER 3 And If the Band You’re in Starts Playing Different Tunes:The Dark Side of the Moon Is Born

CHAPTER 4 Forward, He Cried from the Rear: Into Abbey Road

CHAPTER 5 Balanced on the Biggest Wave: Dark Side, Phase Three

CHAPTER 6 And When at Last the Work Is Done: The Dark Side of the Moon Takes Off

Appendix Us and Them: Life After The Dark Side of the Moon

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography/Sources

Acknowledgements

Index

About the Author

About the Publisher

Dedication (#ub83159fc-50d4-5db5-822f-ccd753fc943d)

For Hywel, who was right.

Prologue January 2003 (#ub83159fc-50d4-5db5-822f-ccd753fc943d)

‘I don’t miss Dave, to be honest with you,’ said Roger Waters, his voice crackling down a very temperamental transatlantic phone line. ‘Not at all. I don’t think we have enough in common for it to be worth either of our whiles to attempt to rekindle anything. But it would be good if one could conduct business with less enmity. Less enmity is always a good thing.’

He was speaking from Compass Point Studios, the unspeakably luxurious recording facility in the Bahamas whose guestbook was filled with the signatures of stars of a certain age and wealth bracket: the Rolling Stones, Paul McCartney, Eric Clapton, Joe Cocker. Waters was temporarily resident there to pass final judgement on the kind of invention with which that generation of musicians were becoming newly acquainted: a 5.1 surround-sound remix, one of those innovations whereby the music industry could persuade millions of people to once again buy records they already owned.

No matter that Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon had already been polished up to mark its twentieth anniversary in 1993; having been remixed afresh, it was about to be packaged up in newly designed artwork, and re-released yet again. Its ‘30th Anniversary SACD Edition’ would appear two months later, buoyed by an outpouring of nostalgia, and the quoting of statistics that had long been part of its authors’ legend.

The fact that they had the ring of cliché mattered little; Dark Side’s commercial achievements were still mind-boggling. In the three decades since it appeared, the album had amassed worldwide sales of around thirty million. In its first run on the US album charts, it clocked up no less than 724 weeks. In the band’s home country, it was estimated that one in five households owned a copy; in a global context, as Q magazine once claimed, with so many copies of Dark Side sold, it was ‘virtually impossible that a moment went by without it being played somewhere on the planet’.

That afternoon at Compass Point, Waters devoted a couple of hours to musing on the record’s creation, and its seemingly eternal afterlife. ‘I have a suspicion that part of the reason it’s still there is that successive generations of adolescents seem to want to go out and buy The Dark Side of the Moon at about the same time that the hormones start coursing around the veins and they start wanting to rebel against the status quo,’ he said. When asked what the record said to each crop of new converts, he scarcely missed a beat: ‘I think it says, “It’s OK to engage in the difficult task of discovering your own identity. And it’s OK to think things out for yourself.”’

As he explained, Dark Side had all kinds of themes: death, insanity, wealth, poverty, war, peace, and much more besides. The record was also streaked with elements of autobiography, alluding to Waters’s upbringing, the death of his father in World War II, and the fate that befell Syd Barrett, the sometime creative chief of Pink Floyd who had succumbed to mental illness and left his shell-shocked colleagues in 1968. What tied it all together, Waters said, was the idea that dysfunction, madness and conflict might be reduced when people rediscovered the one truly elemental characteristic they had in common: ‘the potential that human beings have for recognizing each other’s humanity and responding to it, with empathy rather than antipathy’.

In that context, there was no little irony about the terms in which he described the album’s place in Pink Floyd’s progress. In Waters’s view, the aforementioned statistics concealed the Faustian story of the band finally achieving their ambitions, and thus beginning the long process of their dissolution. ‘We clung together for many years after that – mainly through fear of what might lie beyond, and also a reluctance to kill the golden goose,’ he said. ‘But after that, there was never the same unity of purpose. It slowly became less and less pleasant to work with each other, and more and more of a vehicle for my ideas, and less and less to do with anyone else, so it became less and less tenable.’ In the words of Rick Wright, at the time Dark Side was created, ‘it felt like the whole band were working together. It was a creative time. We were all very open.’ Thereafter, Waters became so commanding that the possibility of any such joint endeavour was progressively closed down.

Naturally, you could hear some of this in the music. The band’s collective personality on Dark Side is warmly understated – a quality embodied in the gentle vocal blend of Wright and David Gilmour – and most of the sentiments expressed are intentionally universal: within the sea of personal pronouns in Waters’s lyrics, none occurs as often as ‘you’. From 1975’s Wish You Were Here onwards, however, Waters recurrently vented the very specific concerns of an increasingly troubled rock star. Underlining the change, as of Pink Floyd’s next album, 1977’s rather bilious Animals, Gilmour’s vocals were nudged to one side, while Waters’s unmistakable mewl became the band’s signature.

All this reached its conclusion on The Wall, the 1979 song-cycle-cum-grand-confessional-and-concert-spectacular that, in financial terms at least, achieved feats that even Dark Side hadn’t managed. Arguably the greatest achievement on Dark Side is ‘Us and Them’, a lament for the human race’s eternal tendency to divide itself into warring factions. By the time of this new project, which Waters still believes is of a piece with the band’s best work (‘I think The Wall is as good as The Dark Side of the Moon – I think those are the two great records we made together’), Pink Floyd’s music suggested one such example: Roger Waters versus the rest of the world.

Where Dark Side oozed a touching generosity of spirit, The Wall was bitterly misanthropic. Though the former combined its melancholy with hints of redemptive optimism, the latter seemed unremittingly bleak. And if the 1973 model of Pink Floyd had been a genuinely collective endeavour, by 1979, Gilmour, Wright and Nick Mason were very much supporting players (indeed, Wright had been sacked during The Wall sessions). All this reached a peak with 1983’s The Final Cut – according to its credits, ‘A requiem for the post-war dream by Roger Waters, performed by Pink Floyd.’ In its wake, Waters expressed the opinion that the band was ‘a spent force creatively’, announced his exit, and assumed that the story had drawn to a close. At least one account of this period claims that Waters’s parting shot to his colleagues was ‘You fuckers – you’ll never get it together.’

Much to Waters’s surprise – and against the backdrop of a great deal of legal tussling – Gilmour eventually decided to prolong the band’s life, creating his own de facto solo record, 1987’s A Momentary Lapse of Reason, and then enlisting Mason and Wright – the latter as a hired hand rather than an equal partner – for a world tour that found the group earning record-breaking receipts and settling into the life of a stadium attraction. In 1994, they released their second post-Waters album, The Division Bell, and commenced a vast world tour partly sponsored by Volkswagen. ‘I see no reason to apologize for wanting to make music and earn money,’ said Gilmour. ‘That’s what we do. We always were intent on achieving success and everything that goes with it.’

Waters, watching from afar, could not quite believe that Pink Floyd now denoted a group whose live presentations were built around an eight-piece band, and whose latest album featured songs credited to Gilmour and his wife, an English journalist and writer named Polly Samson. ‘I was slightly angry that they managed to get away with it,’ he said in 2004. ‘I was bemused and a bit disappointed that the Great Unwashed couldn’t tell the fucking difference … Well, actually they can. I’m being unkind. There are a huge number of people who can tell the difference, but there were also a large number of people who couldn’t. But when the second album came out … well, it had got totally Spinal Tap by then. Lyrics written by the new wife. Well, they were! I mean, give me a fucking break! Come on! And what a nerve: to call that Pink Floyd. It was an awful record.’

So it was that Gilmour and Waters had arrived at the impasse that defined their relations in the early twenty-first century. The upshot in 2003 was clear enough: a record partly based on the desirability of greater human understanding was being promoted by two men who had not spoken for at least fifteen years.

The week that Waters arrived at Compass Point, David Gilmour – long known to his friends and associates as Dave, before insisting on his full Christian name at some point during the 1990s – was at his home in Sussex, apparently embroiled in distanced negotiations with his old friend and colleague. ‘We’re in secondhand contact,’ he explained. ‘James Guthrie, our engineer, is remixing the album. Roger listens to it and I listen to it, and we both give our comments and have our little battles over how we think it should be through someone else. I’ve just had no contact with Roger since ‘87 or something. He doesn’t seem to want any. And that’s fine.’

Gilmour responded to questions about The Dark Side of the Moon with his customary reserve, couching a great deal of what he said in a businesslike kind of modesty. The record might have been elevated into the company of the nine or ten albums that go some way to defining what rock music is (or perhaps used to be): Highway 61 Revisited, Revolver, Pet Sounds, The Band, Led Zeppelin IV, et al. It undoubtedly continued to send thousands of listeners into absolute raptures. Yet at times, Gilmour still sounded surprised by what had happened. When asked about his memory of first appreciating the album in its entirety, he said this: ‘I don’t think any of us were in any doubt that we were moving in the right direction, and what we were getting to was something brilliant – and it was going to be more critically and commercially successful than anything we’d done before … I knew that we were moving up a gear, but no one can anticipate the sales and chart longevity of that nature.’

Every now and again, he could allow himself a laugh at the kind of absurdity that comes with such vast success. There was a gorgeous irony, for example, in the fact that Roger Waters had intended Dark Side’s lyrics to be unmistakably direct and simple, only to see all kinds of erroneous interpretations heaped on them – not least the absurd theory, circulated in the mid-1990s, that Dark Side had been created as a secret soundtrack to The Wizard of Oz. ‘I think Roger had got sick of people reading everything wrongly,’ said Gilmour. ‘He was always talking about demystifying ourselves in those days. And The Dark Side of the Moon was meant to do that. It was meant to be simple and direct. And when the letters started pouring in saying, “This means this, and this means that,” it was “Oh God.” But as the years go by, you realize that you’re stuck with it. And thirty years later you get The Wizard of Oz coming along to stun you. Someone once showed me how that worked, or didn’t work. How did I feel? Weary.’

As had become all but obligatory in his interviews, Gilmour also reflected on the creative chemistry that had once defined his relationship with Waters and fired the creation of Pink Floyd’s best music. ‘What we miss of Roger,’ he said in 1994, ‘is his drive, his focus, his lyrical brilliance – many things. But I don’t think any of us would say that music was one of the main ones … he’s not a great musician.’ Nine years on, he was sticking to much the same script: ‘I had a much better sense of musicality than he did. I could certainly sing in tune much better [laughs]. So it did work very well.’

Over in the Bahamas, Roger Waters had angrily pre-empted any such idea. ‘That’s crap,’ he said. ‘There’s no question that Dave needs a vehicle to bring out the best of his guitar playing. And he is a great guitar player. But the idea, which he’s tried to propagate over the years, that he’s somehow more musical than I am, is absolute fucking nonsense. It’s an absurd notion, but people seem quite happy to believe it.’

All that apart, and presumably to Waters’s continuing annoyance, Gilmour was still the effective custodian of the Pink Floyd brand name. His last performance under that banner had taken place on 29 October 1994, in the echo-laden surroundings of Earls Court arena; poetically – and in brazen denial of its chief architect’s continued absence – the show had been built around a rendition of The Dark Side of the Moon. Now, when asked about the prospects of any further Pink Floyd records or performances, he sounded jadedly noncommittal. ‘At the moment, it’s something so far down my list of priorities that I don’t really think about it. I don’t have a good answer for you on that. I would rather do an album myself at some point, and get on with other things for the time being. Would I rule it out? Mmmm. Not a hundred per cent. One never knows when one’s vanity is going to take one.’

In June 2005, there came news so unlikely as to seem downright surreal. After a period of estrangement lasting two decades, Roger Waters and David Gilmour announced that they would both participate in a Pink Floyd reunion at the London Live 8 concert. ‘Like most people, I want to do everything I can to persuade the G8 leaders to make huge commitments to the relief of poverty and increased aid to the third world,’ read a statement issued by Gilmour. ‘Any squabbles Roger and the band have had in the past are so petty in this context, and if re-forming for this concert will help focus attention then it’s got to be worthwhile.’

Waters, meanwhile, issued a communiqué that sounded a slightly more gonzo note than his reputation as one of rock music’s intellectual sophisticates might have suggested. ‘It’s great to be asked to help Bob [Geldof] raise public awareness on the issues of third world debt and poverty,’ he said. ‘The cynics will scoff – screw ’em! Also, to be given the opportunity to put the band back together, even if it’s only for a few numbers, is a big bonus.’ His return, however temporary, seemed to provide retrospective confirmation that the Pink Floyd who had authored A Momentary Lapse of Reason and The Division Bell had not been the genuine article, though the Gilmour statement came with a slightly different spin: ‘Roger Waters will join Pink Floyd to perform at Live 8’ ran the headline on the official Pink Floyd website.

The group’s performance at Hyde Park – ‘Breathe/Breathe Reprise’, ‘Money’, ‘Wish You Were Here’ and ‘Comfortably Numb’, delivered with a poise and understatement that only served to enhance the music’s impact – sent interest in the Floyd’s music sky-rocketing; according to the Independent, the day after Live 8 found sales of the career anthology Echoes rising by 1,343%. Talk of a lasting rapprochement, however, was quickly squashed (for all the show’s wonders, Gilmour said the experience was as awkward as ‘sleeping with your ex-wife’). For the time being, their creative history thus remains sealed, long since hardened by hindsight into a picture of peaks, troughs and qualified successes.

To take a few example at random, 1967’s The Piper at the Gates of Dawn is fondly loved by a devoted fan-cult, and couched in the semi-tragic terms of an artistic adventure that was ended far too soon. Ummagumma (1969) is treasured by only hardened disciples; Wish You Were Here often seems as worshipped as The Dark Side of the Moon. Animals and Meddle (1971) are the kind of records that those who position themselves a little higher than the average record-buyer habitually claim to be underrated and overlooked – and when The Wall enters any discussion, its champions often shout so passionately that any opposing view is all but drowned out.

By way of underlining Waters’s view of their history, the two albums that Gilmour piloted in his absence are rarely mentioned these days. The accepted view of their merits is that they represented ‘Floyd-lite’, an invention that worked very well as a means of announcing mega-grossing world tours, but hardly stood up to the band’s best work. That said, the idea that most of Pink Floyd’s brilliance chiefly resided in the mind of Roger Waters has been rather offset by the underwhelming solo career that began with 1984’s The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking – proof, despite the occasional glimmer of brilliance, that he too is destined to toil in the slipstream of the music he created in the 1970s.

The record with the most inescapable legacy is, of course, The Dark Side of the Moon – an album whose reputation is only bolstered by the fascinating story of its creation. Far from being created in the cosseted environs of the recording studio, it was a record that lived in the outside world long before it was put to tape: played, over six months, to audiences in American cities, English towns, European theatres, and Japanese arenas, while it was edited, augmented, and honed by a group who well knew they were on to something.

Perhaps most interestingly, it is a record populated by ghosts – most notably, that of Syd Barrett. In seeking to address the subject of madness, and question whether the alleged lunacy of particular individuals might be down to the warped mindset of the supposedly sane, Roger Waters was undoubtedly going back to one of the most traumatic chapters in Pink Floyd’s history – when their leader and chief songwriter, propelled by his prodigious drug intake, had split from a group who seemed to have very little chance of surviving his departure. For four years after Barrett’s exit, through such albums as A Saucerful of Secrets, Atom Heart Mother, and Meddle, they had never quite escaped his shadow; there is something particularly fascinating about the fact that the album that allowed them to finally break free was partly inspired by his fate.

All that aside, Dark Side is the setting for some compellingly brilliant music. There are few records that contain as many shiver-inducing elements: the instant at which the opening chaos of ‘Speak to Me’ suddenly snaps into the languorous calm of ‘Breathe’; just about every second of ‘The Great Gig in the Sky’ and ‘Us and Them’; the six minutes that begins with ‘Brain Damage’ and climaxes so spectacularly with ‘Eclipse’. Nor are there many examples of an album being defined by a central concept that would be so enduring. Other groups have come up with song-cycles based on ancient legend, the sunset of the British Empire, futuristic dystopias, and pinball-playing messiahs. Pink Floyd, to their eternal credit, opted to address themes that would, by definition, endure long after the record had been finished, and the band’s bond had dissolved.

That Dark Side hastened that process only adds to the story’s doomed romance. ‘With that record, Pink Floyd had fulfilled its dream,’ said Roger Waters, as the transatlantic static fizzed and he prepared to return to Dark Side’s new remix. ‘We’d kind of done it.’

Over in England, David Gilmour had voiced much the same sentiments; if only on that one subject, he and his estranged partner seemed to be united. ‘After that sort of success, you have to look at it all and consider what it means to you, and what you’re in it for: you hit that strange impasse where you’re really not very certain of anything any more. It’s so fantastic, but at the same time, you start thinking, “What on earth do we do now?”’

CHAPTER 1 (#ub83159fc-50d4-5db5-822f-ccd753fc943d)

The Lunatic Is in My Head (#ub83159fc-50d4-5db5-822f-ccd753fc943d)

Syd Barrett and the Origins of Pink Floyd (#ub83159fc-50d4-5db5-822f-ccd753fc943d)

On 22 July 1967, the four members of Pink Floyd were en route to the city of Aberdeen, the most northerly destination for most British musicians. The next night, they would call at Carlisle, where they would share the stage with two unpromisingly-named groups called the Lemon Line and the Cobwebs. Such was the life of a freshly successful British rock group in the mid-to-late 1960s: a seemingly endless trek around musty-smelling ballrooms, where the locals might be attracted by the promise of seeing the latest Hit Sensation, and musicians could be sure of being rewarded in cash. If London proved too far for a drive home, they and their associates would be billeted to a reliably dingy bed and breakfast.

If this aspect of Pink Floyd’s life hardly suggested any kind of glamour, they could take heart from the fact that they were – for the moment at least – accredited pop stars. The week they arrived in Aberdeen, their second single had climbed to number six in the UK singles charts, nestling just below The Beatles’ ‘All You Need Is Love’ and Scott McKenzie’s ‘San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Some Flowers in Your Hair)’. As with their first effort, ‘Arnold Layne’, ‘See Emily Play’ was a perfect exemplar of the influences wafting into Britain from the American West Coast being rewired into a very English sense of fairy-tale innocence, an impression only furthered by the Old World elegance of its lyrics, established in the opening line: ‘Emily tries/But misunderstands …’

The single’s success had been boosted by a run of appearances in the kind of magazines that treated their subject matter with a breathless superficiality – like Disc and Music Echo, a weekly that tended to portray musicians as short-lived items on an accelerated production line. The day Pink Floyd were in Aberdeen, it honoured them with its cover, accompanied by a set of pen-portraits, doubtless bashed out in a matter of minutes.

Roger Waters, said the magazine, ‘likes to think he is a hard man, and in fact he can be very evil … He only listens to pop music because he has to.’ Maintaining the sense of a kind of withering demystification, Nick Mason was accused of getting ‘a kick out of being nasty to people – he likes people to be frightened of him, because he is someone of whom you could never be frightened.’ Rick Wright, meanwhile, was ‘the musician of the group, and also very moody. He has written hundreds of songs that will never be heard because he thinks they are not worthy.’

The most lengthy character sketch was given over to Syd Barrett. Pink Floyd’s singer, guitarist, and chief songwriter was described as ‘the mystery man of the group – a gypsy at heart … he loves music, painting and talking to people … totally artistic … believes in total freedom – he hates to impede or criticise others, and hates others to criticise others or impede him.’ Barrett, it was claimed, ‘doesn’t care about money and isn’t worried about the future.’

If such words suggested a blithe kind of contentment, the reality of Barrett’s life was rather different. His London home was shared with people reputed to be ‘messianic acid freaks’, fond of introducing their acquaintances to LSD on the slightest pretext. Barrett’s familiarity with the drug long predated his arrival in their company, but his housemates were hardly ideal companions: by now, Barrett’s acid use was beginning to manifest itself in chronic mood swings that could lead to either raging anger – and occasional violence – or spells of near-catatonia.

Inevitably, all this was starting to have an impact on the group’s working lives. Seven days after the Aberdeen show, Pink Floyd played at a huge London event grandly titled The International Love-In. Mere minutes before stage-time, Barrett had gone AWOL; an associate of the band eventually found him, ‘absolutely gaga, just totally switched off, sitting rigid, like a stone.’ Pushed onto the stage, Barrett remained pretty much silent, apart from the odd moment when he decided to pull flurries of discordant notes from his guitar. Though his three colleagues did their best to somehow cover up for him, it was clear that something was wrong: in the wake of the show, reports in the music press made mention of ‘nervous exhaustion’.

Nonetheless, Pink Floyd’s work-rate hardly slowed down. By September, they were in Scandinavia. Six weeks later, after another run of British shows, they took off for their first tour of the United States, during which Barrett’s problems would worsen: the most-documented episodes from this period are an appearance on the Pat Boone Show that saw Barrett reacting to his host’s questions with a glassy-eyed stare and large-scale silence, and a three-minute spot on American Bandstand in which Barrett reacted to the instruction that he should mime to ‘See Emily Play’ by keeping his mouth resolutely shut.

It is some token of the band’s frenetic schedule that two days after they returned to the UK, they were back on tour, this time in the company of Jimi Hendrix. ‘There was a bit of “Syd’ll pass out of it, it’s only a phase,”’ says Nick Mason. ‘And I think we were anxious to make Syd fit in with what we wanted, rather than giving all our efforts to seeing if we could make him better. We probably said, “Oh well – let’s try and keep working.”

‘Even now,’ says Mason, ‘I’m astonished. How could we have been so blinkered, or so silly, or so stupid?’

When talking to those who once shared Barrett’s company, one facet of his story becomes clear: rather than the astral, saucer-eyed waif of legend, he was initially a gregarious, enthusiastic presence. ‘He was a very friendly soul,’ says Nick Mason. ‘At my first meeting, I can remember him bounding up and saying, “Hello, I’m Syd” – at a time when everyone else would have been cool, staring around the room in a rather studied way, rather than introducing themselves.’

‘Syd was good fun,’ says Peter Jenner, half of Pink Floyd’s initial management team. ‘He and I would sit around and smoke dope, listen to records, talk about things. Sharp? Absolutely. I had no idea that he was going to go loopy; there was no indication. I had enormous respect for him, to the point of being overwhelmed: he did these paintings, and he wrote all these songs, and he played the guitar … he was full of ideas.’

Barrett was born Roger Keith Barrett on 6 January 1946, and grew up in Cambridge. His father, Dr Arthur Barrett, was a hospital pathologist; his mother, Winifred, was a housewife, who shared with her husband a love of classical music, and a wish to encourage their children’s creative side via regular family ‘music evenings’. Dr Barrett died when Syd was fifteen; by that point, he had given his youngest son (Syd had two brothers and two sisters) a guitar, and Syd had begun to make contact with like minds. By 1962, he was the guitarist with a Cambridge band – in thrall to the standard beat-group archetype of the day – called Geoff Mott and the Mottoes, whose rehearsals tended to take place in the front-room of the Barrett family home. Among their circle of intimates was Roger Waters: two years older than Syd, but happy, for now, to leave the slippery art of musicianship to his younger friend. ‘Syd was a little ahead of me,’ says Waters. ‘I was very much on the periphery. I can remember designing posters for Geoff Mott and the Mottoes, quietly wanting to be a bit further towards the centre of things.’

Barrett’s musical activities, along with a talent for painting that led him to enrol at Cambridge’s College of Art and Technology, soon drew him to the city’s young in-crowd: a coterie of late-adolescent bohemians who would gather at the Criterion, a shabby pub located in Cambridge’s centre. He and Waters were soon among the regulars, sharing the company of a guitarist and teenage language student named David Gilmour, and Storm Thorgeson and Aubrey Powell, whose immediate ambitions lay, slightly vaguely, in film and photography.

‘The thing that really struck me about Syd was that he was a kind of elfin character,’ says Aubrey Powell. ‘He walked slightly on his tiptoes all the time, and he used to sort of spring along. He always had a wry smile on his face, as if he was laughing at the world, somehow. And he was always something of a loner: you could be with a group of people and suddenly Syd would be gone. He’d just evaporate, and then two days later he’d return. He was very much his own person.

‘What I really liked about him was this weird attention to detail. One day I went into his room, and he said, “Look at these.” There were these three dodecahedrons hanging from the ceiling, all immaculately made from balsa wood: absolutely perfectly done. They were big, too. And I remember thinking, “God, the patience to do that …”’

In the view of outsiders, Cambridge has a strong self-contained identity, forever bound up with the university that attracts thousands of tourists to the city – but also cleaves the local population into Town and Gown. Indeed, for most young people born and raised in Cambridge, the colleges are irrelevant, strangely distant institutions; far more important is the close proximity of London.

Back in the 1960s, Syd Barrett, Roger Waters and their friends were a perfect case in point. By the summer of 1964, the crowd centred on the Criterion was fast dissipating: Barrett had taken a place at Camberwell Art School, while Waters was readying himself for studying architecture at the Regent Street Polytechnic. The latter took very little time to make the move that, back in Cambridge, had always eluded him: drawing on his circle of newfound London friends, he formed a group called Sigma 6 and appointed himself its lead guitar player.

Waters’s colleagues included a bass player named Clive Metcalf, vocalists Keith and Sheila Noble – and a drummer and rhythm guitarist who numbered among Waters’s fellow architecture students. So it was that Nick Mason and Rick Wright entered the picture; to be joined – after Waters had been nudged from lead guitar to bass, Wright had decided to play keyboards, and the band’s more peripheral members had been pushed out – by Syd Barrett. He advised his new band that, having already passed through such ill-advised names as the T-Set, the Megadeaths, and the Abdabs – they should call themselves the Pink Floyd Sound, in partial tribute to two of his favourite blues singers, Pink Anderson and Floyd Council.

The group played their first show in late 1965 and began moving along the musical trajectory that would define their first career chapter. Like most groups of their era, they were partial to beat-group standards like ‘Louie Louie’ and ‘Road-runner’, but they would use such songs as book-ends to extended passages when, led by Barrett, they would step away from three-chord orthodoxy and begin to improvise. It is not hard to draw a line between such flights of musical fancy and Barrett’s drug habits: certainly, though his colleagues were not nearly as quick to ingest illicit substances, it’s a matter of record that by the time of the Pink Floyd Sound’s first manoeuvres, Barrett was well acquainted with both cannabis and LSD.

In the summer of 1966, Peter Jenner, then a young economics graduate, chanced upon a Pink Floyd Sound performance at the Marquee, the London club where The Who had cut their teeth. ‘I was very into the idea of the young, groovy avant-garde,’ he recalls. ‘And I thought this would be a young, groovy, avant-garde show. I got there and I saw the Floyd, and I thought they were remarkable, because I couldn’t work out where each noise was coming from. The Marquee had a stage that kind of stuck out, and I was endlessly walking around it, just trying to figure it out.

‘They were playing these really lame old tunes, like “Louie Louie” and all these hackneyed blues songs – not much of Syd’s stuff. But in the middle, there were all these weird bits going on: what I subsequently discovered were one-chord jams. Instead of there being a blues solo, there was a weird solo. And I liked that. I couldn’t work out where the noise was coming from: whether it was guitar, or organ, or what. I just thought, “Christ, this is interesting.”’

By 1966, a close-knit crowd of Londoners was beginning to coalesce into what would become known as the Underground. They formed a network of young creative people, plugged into a variety of cultural currents: the thrilling sense of possibility embodied by the recent – and unprecedented – success of English rock groups, led by the Beatles and Stones; a burgeoning drug culture; a thawing of social strictures that would soon be embodied in the legalization of abortion and homosexuality; and an economic climate that had given rise to full employment. Of no less importance were a slew of influences taken from the United States: the Beats, Bob Dylan, and most importantly of all, the freshly-born West Coast counterculture – news of which had recently crossed the Atlantic.

Suitably inspired, those at the centre of London’s bohemian milieux were starting to set up their own equivalent. The first issue of a weekly countercultural newspaper, International Times (aka IT), would be published in October 1966. Soon after, a late-night weekly event called UFO began in the unlikely environs of an Irish-themed London establishment called the Blarney Club. Elsewhere, art galleries, bookshops and music events were adding to the sense of a slow-building cultural upsurge.

The philosophical threads that held it all together were as varied as its constituent elements, but the Underground was unquestionably characterized by a shared agenda. Whereas previous radical movements had focused on the wish for change enacted on a grand scale – this being Great Britain, social class remained integral to most critiques of society – the sixties generation placed a new emphasis on the freeing of the individual, who would be liberated, according to the Underground’s louder voices, by embracing the kind of multi-coloured hedonism that defined London’s hipper social circles.

According to Richard Neville, the Australian émigré who contributed to London’s counterculture by editing the magazine Oz, ‘The aim of the alternative culture was to shake up the existing situation, to break down barriers not only between sexes and races and God knows what else, and it was also to have a good time … to enlarge the element of fun that one had occasionally in one’s own life and to make that more pervasive – not just for you but for everyone. I was quite keen to abolish this work/play distinction. There was something incredibly oppressed about the mass of grey people out there. I just thought that people on the whole looked unhappy: they seemed to be pinched and grey and silly and caught up with trivia, and I felt that what was going on in London would bring colour into those grey cheeks and those grey bedrooms. With a bit of sexuality and exciting music and flowers … somehow the direction of society could be altered.’

If Syd Barrett’s lifestyle implicitly allied him with the Underground’s thinking, Peter Jenner was closely tied to some of its most crucial players. Together with John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins, a co-founder of International Times, he had established a record label called DNA – and, thrilled by what he had seen at the Marquee, Jenner initially approached the Pink Floyd Sound with a view to releasing their records. Led by Roger Waters, they persuaded him to take on the role of manager. In partnership with his longstanding friend and sometime employee of British Airways, Andrew King, Jenner thus founded the grandly-named Blackhill Enterprises and began to assist his new clients. His first move was inspired: suspecting that the Pink Floyd Sound lent them an unbecoming air of vaudevillian corniness, he convinced them to trade as The Pink Floyd.