Полная версия:

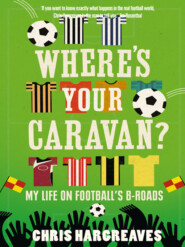

Where’s Your Caravan?: My Life on Football’s B-Roads

Chris Hargreaves

Where’s Your Caravan?

Dedication

To my beautiful family, Fiona, Cameron, Isabella

and Harriet. I am one lucky man.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Where’s your caravan?

Early Days

1989/90

1990/91

1991/92

1992/93

1993/94

1994/95

1995/96

1996/97

1997/98

1998/99

1999/2000

2000/01

2001/02

2002/03

2003/04

2004/05

2005/06

2006/07

2007/08

2008/09

2009/10

Epilogue

Copyright

About the Publisher

Where’s your caravan?

Well, at the moment, metaphorically speaking (and yes, I know I have used a big word in the first sentence but don’t judge me yet, I may still confirm your suspicions) my caravan is parked up in the middle of Devon. It has an electricity and water hook up, and is on a nice little pitch. I don’t plan on moving it very soon but, if my career path is anything to go by, the chocks could be removed at any time and it could roll on out of town once more.

So why have I titled this book as I have? Well, for starters the nomadic lifestyle of a gypsy travelling around the country, stopping every so often to enjoy the local area and find some work, is very familiar to me. I wouldn’t go so far as to say it also gives my trusty old horse a rest as well, as my wife Fiona may not appreciate being likened to an old nag! However, I have played for ten clubs and have moved house fifteen or so times, gradually migrating from north to south, so I can definitely empathise with the uncertain lifestyle of the traveller.

The second reason I have titled the book as I have is that for the vast majority of the seven hundred odd professional games I have played in (or been present at anyway!) the chorus of ‘Where’s your caravan?’ has reverberated around the main stand of the many grounds I have been to (and many times those main stands have been a bit sparsely filled, so you can imagine the quality of the acoustics in these cavernous spaces, and the clarity of the words). OK, so it may have been prompted by a slightly late tackle by yours truly, or a shot into row Z, but it is more likely that my long hair has caused many a punter to assume that I am, in fact, a gypsy traveller. I got used to this form of harmless banter/abuse, and whenever I heard it sung I would usually point to the car park, which would give the away fans a good laugh, and get me off the hook for taking out their number nine.

I’m not the only player who gets this type of stick. While playing for Torquay United a few years ago, we had a pre-season game against Derby, and who should be in their team but a certain Mr Robbie Savage (I think of him as a poor Chris Hargreaves – poor in skill, but perhaps richer in other ways). I had to laugh when the inevitable chant of ‘Where’s your caravan?’ was sung to him and, instead of pointing to the car park as I used to do, he shouted over to the main stand and said, ‘It’s in Monaco, lads.’

Old Robbie, if ever there was a man who could drive a yellow Ferrari it was him; I would say it matched his teeth, but after his latest Hollywood treatment this is no longer the case. (Give us the number please Robbie, I’m doing a bit of local TV down here in the south-west!)

Sadly, my career is now over, so that particular song will no longer be heard by me, which is a shame. What’s more, I recently had my hair cut quite severely, which, to some extent, is also a shame, but you can only get away with hair like that for so long. You either have to be a footballer or be in a band, and although I think my shower singing voice has a major chance of world stardom I am as yet unsigned.

I first started trying to write this book a couple of years ago, and my mood at the time could have been described as, at best, reflective. A recent promotion captaining Torquay United – scoring and lifting the trophy at Wembley no less – changed my mood ever so slightly, to that of mild euphoria. I subsequently left Torquay United, rejoined Oxford United, got promoted, got injured and have now retired.

My mood has obviously changed again. I am no longer a professional footballer, and I have to tell you that it is bloody tough. Not tough in the bigger scheme of things, by that I mean the poor souls who have lived through wars, tsunamis, disease, poverty and famine, or the heroes that fight for their country or who work seventy hour weeks saving lives in hospitals and operating theatres up and down the land. That is tough. By ‘tough’, I mean that football is all I have ever known and I never really imagined the end coming, even though I knew it had to. I would say I am definitely now in the real world. I still don’t like to say the word ‘retired’ (I must get used to saying ‘ex-footballer’ by the way) and part of me thinks I could still play; it’s difficult to know how I feel at the moment, but I will try to tell you during the course of this book.

I suppose what I am trying to get at is that, in the space of a couple of years, my life has been amazing, disappointing, exciting, and many other things ending with the letters ‘ING’. My writing style may therefore be a little bit varied, but they say everyone has a book in them, so I thought I would give it a go. Add to this, my life off the field, with my three lovely/demanding children and my lovely/very demanding wife, the many miles of motorway driving I have recently done to and from Devon, and the numerous nights spent in hotels, and you may start to see a picture of the life and mindset of a professional footballer.

I have mild to high OCD, I have got slight neuroses, and I am a practising, but reluctant, insomniac. I also seem to spend my life on the phone or computer trying to keep as many fingers in as many pies as possible, in order to bolster my chances of finding work, and money, after football. I am very lucky, or very unlucky depending on your viewpoint, to have played for as long as I have, but it is now over. Retirement from football ended my staying in hotels, smuggling in my boxes of Shreddies and M&S dinners, and smuggling out the hotel shampoo, tea and coffee supplies. I didn’t predict the ending and although I had tried to make a few plans for the future, towards the latter part of my career, right up until the end, football was totally and utterly my life.

I will intersperse my writing with little gems from my Devon clan, such as Hattie, our four-year-old firecracker who bosses us all about something chronic, tells me her friends have polar bears and lions for pets and has demanded ham, cheese and Toblerone for breakfast. She will break dance on request, loves being naked, and is ‘marrying Will next door’ who IS her boyfriend (yes, you guessed it, she takes after her mother!). The older two, Cameron and Isabella, consistently squabble over the TV control, are as competitive as gladiators, and are constantly planning which adventure ‘we’ will go on next. I don’t want any of them to grow any older, and I regularly tell the girls to never leave me. In truth, I love those goof balls so much it does actually hurt sometimes.

I will also tell you where I am writing from at any particular time – I started this section while in a hotel reception listening to a supermarket-style loop tape and watching numerous afternoon business lunches escalate into all-day sessions – no wonder those bankers have made such bad decisions recently!

In short, I will try to re-live with you the last twenty or so seasons of my football career. This will include spells at ten clubs, and having seen a good twenty-five managers come and go. It will include tales of fans, players and chairmen alike, it will contain more house moves than a Kirstie Allsopp book, and it will chart some of the seven hundred and fifty or so games that I have played in. At times I have hated this job with a passion, usually after defeats I might add, but I hope this book will give you an insight into why I still love the game that I have been paid to play for over twenty years. I hope that the young professionals starting out can learn from it, I hope that old pros coming to an end of their careers can empathise with it, and I hope that the bloke down the pub can relate to it. It’s about being a dad, a husband and, of course, a footballer.

For all you nature lovers out there, this is the story of Tarzan, Jane and our three little cheetahs, and I will even throw in a bald eagle and a mad dog.

Early Days

‘You can be Grimsby’s first million pound player, if you would just realise it’, and, ‘I’m going to be letting you go, Chris.’

Those two comments came from two different managers within the space of four seasons: from a hot-tempered Alan Buckley at Grimsby Town, and a meek and mild Terry Dolan at Hull City. If you ask me, that was, and is, football in a nutshell. The fine line between success and failure, the bizarre twists of fate, and the never ending desire to prove yourself, are what gives this beautiful game its attraction.

Add to that the great wins, frustrating draws, and infuriating losses, as well as the fair few terrible refereeing decisions, and you have all the ingredients for a story of a footballer’s life.

Football was my life from an early age. I played it, watched it, dreamed it, ate it, and slept it. I would kick a ball around for hours on end at the park, do hundreds of kick-ups in the back garden when I got home, and I would polish my boots to a military standard before placing them carefully at the end of my bed. When asked what I wanted to do when I grew up, my answer was unflinchingly sure: ‘I’m going to play football.’

It’s funny really, as my early childhood was certainly not filled with football. My dad didn’t play the game, his passion was with motorbikes – racing, and then later, repairing and selling them in his shop, Martin Hargreaves Motorcycles. He was one of the first to sell Harley Davidsons in the eighties, but the combination of an unforeseen recession and the then need for cheap, local transport meant that he had to switch to selling a more realistic vehicle for the many working on the Humber bank: scooters. Honda 50s and Puch Maxis would be the future.

After a short spell living in a little village called Holton-le-Clay, my parents bought their first shop, in Cleethorpes (if you don’t know where that is, it is next to Grimsby, if you don’t know where Grimsby is, it is near Hull, and if you don’t know where Hull is, just settle for it being up north somewhere). We lived in a flat above the shop. On that same block there was a fish and chip shop, a butcher’s, a Chinese takeaway (housing my first girlfriend, Suzie Wong), and the best sweetshop in town (visited daily, and by around one thousand local kids, to get our ten pence mixes). It was an old-school sweetshop, with rows and rows of jars, all full to the brim with the most colourful-looking treats you could imagine. It was the nearest thing to Willy Wonka’s that I could imagine and, back then, you could easily get ten flying saucers, a couple of refreshers, some sherbet, and a couple of gob stoppers for only ten pence. Looking back now, I remember that there was also a PRIVATE shop on the same row, and that the sweet shop on the row was, in fact, called David Willy’s – absolutely no connection whatsoever – but all the same, a very bizarre combination.

Add to that a cinema, a one-minute walk away, showing Saturday morning matinees of Flash Gordon and the Famous Five, a railway at the end of the street where we would watch our ten pence pieces get flattened by approaching trains (not to be recommended, please do not try this at home), a great park round the corner, and a beach ten minutes away. In short, it was a child’s dream. We even had a model car and train shop opposite, where I would stare through the window and dream of my next Christmas present – usually a thousand piece, degree level, model warplane, or a Scalextric deluxe rally set. Both products always let you down, but they were still coveted by any self-respecting child.

You could leave the house in the morning and have a mini adventure every day. Nowadays, we are so cautious with our own children that some childhoods are as good as lost, spent indoors playing on consoles and staring at screens. However, with constant stories of abuse and abduction in the media, I’m not exactly telling my own children to nip off to the park.

The place had a real community feel. We had a street party near my school on Elliston Street for the Silver Jubilee. We were given jelly, ice cream, and the obligatory huge coin. Even when the annual floods brought the streets and community to a standstill, it would still amuse the kids no end; we would do ridiculous things, such as play in dinghies in the front room, while the parents would be muttering, ‘It’s much worse than last year’ over numerous cups of tea.

With my parents working every hour God sent trying to keep the business going, my brother and I would inevitably get into a few scrapes. Well, to be honest, my brother Mark was pretty angelic (he has since made up for it), whereas my love of all things naughty seemed to know no bounds. I had an unhealthy obsession with lighting small fires around the apartment. (I would now call that ‘chemistry experiments’.) I climbed out of windows for no apparent reason. (I would now call that ‘mountaineering’.) I also had a habit of taking money from the till to keep our local gang supplied with crisps, chocolate, and the immortal Panini stickers. (I would definitely call that ‘borrowing’.) I even lost my poor brother’s new bike on Christmas Day – that was an accident though, as I had completely forgotten to bring it back from the park, though Mark still cites that incident as another case of early psychological torment.

On the whole it was just a bit of harmless fun, and, on the flip side, my sorry letters, posted to my parents under doors after these ‘small’ misdemeanours, really were legendary – ‘No one loves me, but I am still sorry!’

I ended up sliding these apologies under doors to my parents at a pretty alarming rate – a list of my childhood misdemeanours would be massive. A few other examples include the occasion when I lit a fire in the back garden, and threw an aerosol onto it – it flew over the house and onto next-door’s car. One time, I put a lit fire-work into a pocket of my new parka coat; this resulted in me wearing a new coat with one front pocket burnt off. Not all my transgressions involved fire – once I spent a whole day hid up a willow tree, scaring people who came near.

Our back garden was always a hive of activity, it usually being full of bikes, with a workshop at the end of it with even more bikes in it. My dad would spend hours mending his various sidecars, and we would sit in them and pretend to be winning the Grand Prix. My dad was a really good sidecar rider and I spent most weekends in the back of an old orange Commer van going to the many race circuits round the country with my parents and brother.

I ought to clarify what I mean by ‘sidecar’. I mean a low down, twin-passenger racing machine, not as some of you were maybe thinking – a military type bike with a bath welded to it. These racing machines were seriously quick, and, to me, seriously cool. My heroes back then were Jock Taylor and his passenger, Benga Johansson. Jock Taylor was a brilliant rider, and together they had won the sidecar world title and the TT. I was ten when the unthinkable happened – Jock Taylor lost control on a slippery circuit at Imatra during the 1982 Finnish Grand Prix, and crashed fatally. I can always remember seeing that famous number three Yamaha and wanting to be a rider, but the dangers involved back then were huge. Unlike today’s racing, where the run off areas are vast, in both car and bike racing, back then in some cases there were only a few feet, and a few tyres, separating the riders and a fair chunk of concrete, and with speeds of one hundred and seventy miles an hour, it often ended in tragedy. It still does now at the TT (receiving a medal as big as a frying pan, and on a stove, for taking part, should be compulsory for all riders), and one of the major stars of racing back then, Barry Sheene, refused to race there, such was the danger – although smoking, drinking, and partying were also pretty dangerous, and didn’t seem to faze him, but Barry wouldn’t have been Barry without a splash of Brut and a night on the tiles.

(I do realise my mind can spin off at a tangent and I have to apologise about this, but I find it hard to rein it all in. Perhaps my next book can be about racing superstars and war veterans – war is another subject I have a tendency to talk about. Anyway, back to the story!)

Meeting the superstars of the day, such as Barry Sheene and Kenny Roberts at Silverstone and Donington Park, was brilliant. At the meetings, Mark and I would tear around on our own little bikes, while Mum and Dad sold visors, spark plugs, and a whole menagerie of things to do with bikes, on their stall. I may have torn around a bit much on one occasion, as a slight misjudgement of speed and braking distance left me with a nasty scar and broken leg at a local circuit called Cadwell Park. Strangely enough, that same fall and subsequent injury led me to change the foot I used to kick the ball with, going from right to left. I hear you all say, ‘You should use both feet’, as I do now to my son!

Another fall, and a heavily stitched up lip this time, and my parents decided that football would be a safer option. Bizarrely enough, when I was rushed to hospital that time, who should I see on arrival but my mum with my granddad, Sidney. He was a big fella with a big personality, and he was in there to have what Victoria Beckham knows all about, his bunions lanced, sliced, or put back into some sort of shape. I was rushed through to the waiting room where my mum and my granddad were sitting, and when my mum saw me, the towel full of blood, and the sliced lip, she certainly got a shock. I was fine though, and after a few uncomfortable minutes with a needle and thread my lip was as good as new – only a small to medium sized scar on my lip for life, but nothing too serious. I was then lovingly given bag after bag of Midget Gems for the next couple of months. My dad, however, was in the dog house; he had been on childcare duties. I have to be honest though, it was entirely my fault; in my wisdom I had decided to take the brakes off my bike. Footballers eh!

I still loved bikes, and I did take part in quite a few races, but a combination of being beaten in a race by a good old tough northern girl – my bike was thrown to the floor in disgust – and my parents fear for my safety meant that football would definitely become the new passion of my life. I cannot quite remember when I was actually given a ball by my parents, or when I caught the ‘footy’ bug, but a big part of me would have loved to have carried on with the bikes. With football, there are ten other players in a team, a manager, coaches, and many other influencing factors that affect your performance, whereas with racing, barring a bike failure, you are on your own. No excuses, no interference, and I like that idea. I have always been extremely hard on myself throughout my career, but sometimes in this job events are out of your control, and it has taken me a long, long time to realise that. As regards the potential injuries and stitches involved, I may have wished I had persevered with the bikes!

While my parents were very busy with their shop, we did go on a couple of epic holidays when were young – and I’m not just talking about the trip once every five years to Devon. This trip took seventeen hours, included one hundred and fifty games of eye spy, took in fourteen toilet stops, and heard three hundred and one childish shouts of, ‘Are we there yet?’

My children think I’m joking (if they ever start to moan about being bored on long journeys) when I say we had no iPods, DSs, PSPs, DVDs, or even RAC! They then think I am trying to make them laugh when I tell them there was no air con either. These trips would end either with me burying my brother’s ball in the sand and losing it, or with the coastguard being scrambled as I headed for France on a dinghy.

Our two trips abroad were in an entirely different league though.

A camping trip to the South of France conjures up a great image of excitement and adventure for a ten-year-old boy, but little did I know that the trip would end up providing enough adventure for Indiana Jones and all his cronies, never mind for a young lad from Cleethorpes. When our parents decided that we were taking the tranny van (Transit van) to France with some friends of ours, Tina, Dave and their children David and Jane, my brother and I were incredibly excited. Back then, it was a massive deal to be going abroad anywhere.

Tina and Dave were close friends of my parents, and my brother Mark and I got on really well with their children, so it was decided that the two families would jump on board the ‘Cleethorpes express’ – a ten-year-old double wheel base Transit van, modified for two families – and drive to France.

I say ‘modified’ quite lightly, as although my dad did do some vital welding in the van the night we actually left – he welded a swivel chair into it so that one of the mums could check on all the children at any one time and no doubt produce endless supplies of food and drink, and, of course, sick bags – the only other modification really came in the form of the layout of the van.

Instead of the usual cavernous space at the back of the van, my dad and Dave put all the supplies and suitcases needed in first, and then they laid a couple of huge double mattresses on top of each other, and on top of all the cases and supplies. The result was a pretty awesome den for the four kids in the back, but this was definitely in the days before health and safety regulations were given top priority. All four of us were sliding about on those mattresses like it was a big game of Twister on a slippery hill. It was brilliant. We could just about see out of the back window (there was a one foot gap between us and the roof) which was great, and although you may think that it could have been quite dangerous climbing the Pyrenees in a Transit van with four kids sliding about in the back, I think my dad had welded the back doors shut as well, so there would be no re-enactment of the Italian job.

We eventually got there safe and sound, and set up base at Camp Erromardie, in Saint Jean de Luz. We did lots of swimming and playing, and ate a hell of a lot of French bread and cheese. The only variation in our diet was some French bread and jam for dessert. Our day trips took us to some brilliant spots for snorkelling and swimming, although my parents say they still have nightmares now about the distance I would swim out to. On one occasion apparently there was a near full-on coastguard scramble, as a crowd of people that had now gathered on the beach were watching me, worried, as I merrily made my way out towards the headland of one particular bay. I was totally oblivious to it, but you know what it’s like when you have the old flippers and snorkel on, and are looking at the scenery and creatures below.

Very recently, on a trip to a lovely little place called Beer, in Devon, my parents showed me the distance I had snorkelled out to on our French adventure. I honestly thought they were joking, as the point they were talking of was about half a mile out – they were adamant that it was at least that distance. I can now see their concern, and God knows what Fiona would think if she saw our son Cameron do something like that now. I honestly think we would be bringing her round with smelling salts (before she could manage to even put down her skinny decaf latte with no chocolate sprinkles, but accompanying slice of Victoria sponge).