Полная версия:

Faraday: The Life

FARADAY

The Life

James Hamilton

DEDICATION

For my family

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

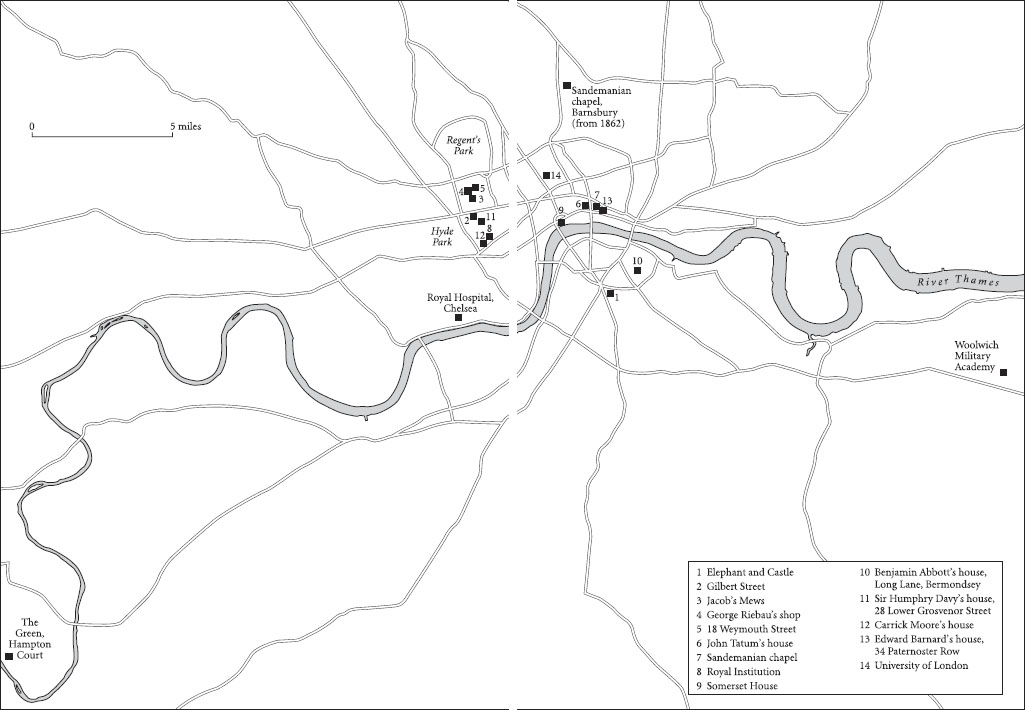

Map: Michael Faraday’s London

Introduction

Chapter 1 ‘The Progress of Genius’

Chapter 2 Humphry Davy

Chapter 3 A Small Explosion in Tunbridge Wells

Chapter 4 ‘The Glorious Opportunity’

Chapter 5 Substance X

Chapter 6 A Point of Light

Chapter 7 Mr Dance’s Kindness Claims my Gratitude

Chapter 8 We have Subdued this Monster

Chapter 9 The Chief of All the Band

Chapter 10 A Man of Nature’s Own Forming

Chapter 11 There they go! There they go!

Chapter 12 Use the Right Word, my Dear

Chapter 13 Fellow of the Royal Society

Chapter 14 We Light up the House

Chapter 15 Steadiness and Placidity

Chapter 16 Facts are Such Stubborn Things

Chapter 17 Crispations

Chapter 18 And that one Word were Lightning …

Chapter 19 Connexions

Chapter 20 The Parable of the Rainbow

Chapter 21 Michael Faraday and the Bride of Science

Chapter 22 Still, it may be True …

Chapter 23 A Metallic Clatter which Effaced the Soft Wave-Wanderings

Chapter 24 I be Utterly Unworthy …

Chapter 25 The More I Look the Less I Know …

Chapter 26 The Body of Knowledge is, After All, But One …

Epilogue

Appendix 1: Faraday’s ‘Philosophical Miscellany’, 1809–10

Appendix 2: Declaration of Faith of Edward Barnard, 1760

Appendix 3: Memorandum to Robert Peel, 1835

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

Faraday: The Biography

By the Same Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Michael Faraday’s London

INTRODUCTION

Setting off from London in October 1813 to travel on the continent, Michael Faraday found the education of an artist in the company of a scientist. He was twenty-two years old when he left England with Sir Humphry Davy, the most famous and admired scientist of his day, taking with him notebooks in which he wrote a unique diary, perceptive, full of incident and detail, of art and antiquities, of scientific experiments and discovery in the making, and of Europe at a moment of unparalleled change. But he took with him also the affection and good wishes of Richard Cosway, as fashionable and controversial a painter as Davy was a scientist, and of the distinguished and level-headed architect George Dance the Younger, and so had the added opportunity of experiencing the antiquities, landscape and history of Europe with the distant guidance of two senior Royal Academicians. With Davy beside him, and Cosway and Dance at home, Faraday’s entourage of mentors was complete.

Faraday’s diary of his eighteen-month continental journey, and the many letters home that surround it, reveals the formation of a man whose scientific discoveries would begin within thirty years to affect through gradual change the lives of every person on the planet.

In the twenty-first century, Michael Faraday’s discoveries and improvements have become given facts and facilities. Electricity comes out of the plug in the wall; shirts and dresses of every subtle shade of dye hang on the rails of clothes shops; we wear spectacles with precision-made lenses, use steel razors, stir tea with electroplated spoons; we fly in aeroplanes free of harm from lightning strikes; we sail in ships warned off rocks by effective lighthouses; and we swim in pools tinctured by liquid chlorine. But in taking a clear occasional glimpse back at the roots of all these standards of modern life, time and again we see the figure of Michael Faraday standing at the distant crossroads.

If Faraday had not made the scientific discoveries he did, somebody else, or a chain of other people, would quite rapidly have done so. Life now would have been recognisably similar but for one particular: Faraday never patented anything. He built no fences around his discoveries to increase personal gain, nor did he market appliances, such as the electric motor or the dynamo, to exploit them. When his experimental ideas were progressing towards the inevitable practical application he passed them on to others. Faraday saw his role as reading ‘the book of nature … written by the finger of God’,1 determining, through experiment, analysis and deduction, a huge network of interconnected scientific principles which he gave as general knowledge to humanity. In doing so, there were no patent fees to pay to him in the nineteenth century, no ‘Faraday and Company’ to give dues to for the use of patterned cloth, razor blades or the generation of electrical power; but also, by now (if all had gone well in the twentieth century) no Faraday Foundation to distribute vast profits to speed the pursuit of happiness. We need to see and understand Faraday in the context of his time and cultural influences if we are to come to a fuller knowledge of the underpinnings of contemporary life. If we know where we have been, we may have a clearer idea of where we may be going.

In this biography I am taking a point of view that stands rather off the main track. Modern biographers of Faraday, writing largely as scientists and historians of science, have drawn portraits of the man which centre on his discoveries and their meanings. If Faraday were a seaside town these would be views of the main square, with all its colour, traffic and purpose. In looking at Faraday in his cultural context, and writing as an art historian with some minor, accidental, university experiences in science, the view I am painting is of the town and its landscape setting from the edge of the bay.

The central influence in Faraday’s life that set him apart from his contemporaries was his religion. He was a devout member of a small, rigid Christian sect, the Sandemanians, whose members took guidance and inspiration from the Bible, and measured their lives against New Testament teaching. In reading God’s book of nature Faraday felt himself to be under direction; Sandemanianism was the rock on which his town was built, keeping him apart from the politics of science, but causing him pain when he strove to reconcile scientific advances with his religious teaching.

Another decisive factor in Faraday’s life was his interest in drawing and painting, in methods of making prints, in the development of photography, in the reproduction of images and in artists as people. This tended to have a lateral effect on his vocabulary: when he searched for words or phrases to describe scientific phenomena, he discovered expressions such as ‘lines of force’, ‘magnetic field’ or ‘crispations’, notions that could be drawn as well as written. When he sought to express to himself scientific ideas in his laboratory notebook he made marginal pen-and-ink drawings of the physical effect as he conceived it in his mind’s eye. Faraday thought in images, would proclaim a successful result ‘beautiful’, and an understanding of the roots of his imagery and the processes of his image-making may lead to a deeper understanding of him as a man. He had little or no mathematics, and his experimental results were reached not by theory and calculation but by observation of physical and visual effects, using instruments of his own devising.

A third fundamental component of Faraday’s personal chemistry was his need to teach people of all kinds and ages, and to lead them to a greater understanding of the natural scientific laws that govern us all. He was the son of a London blacksmith who died young, and of a devout, redoubtable mother. He had himself had a very thin education, of ‘the most ordinary description’, as he put it in later life. Never having experienced the classical education as fragmentarily delivered by the English public and grammar schools, nor a university grounding in Newtonian science, Faraday had no preconceptions, and was thus uniquely receptive when he first encountered science in London. By the same token, when he came to teach he explained his subject clearly and simply, using graphic illustrations and practical demonstrations which enthralled his audiences and sent them home believing themselves to understand perhaps more than they could fully retain.

Working in his laboratory in the basement of the Royal Institution in London, Faraday preferred solitude. The success of his science, however, depended on his learning from others, on consultation, collective endeavour and prayer. The extent of his correspondence with scientists and other friends reflects the passion with which he wanted to discover, discuss, argue and broadcast. He would not say, ‘It is so,’ but ‘Why is it so?’, and would demonstrate why. With a zeal and enthusiasm that was of a new order entirely, Faraday used newly-evolving modern agencies and techniques, such as the public lecture and the press, to get his work known, and to become a public figure himself. He was a natural preacher; from the lecture theatre to the pulpit, standing up so that he could be clearly seen and heard became second nature. Looking at the way he went about things one might almost be studying the activities of a career administrator from the mid-twentieth century. Faraday worked with his employers to reform the fabric, administration, activities and finances of the Royal Institution so that it was in a fit state to teach science to the world. He took highly detailed and particularised notes of every step of his laboratory experiments. His correspondence bound him firmly to the world outside. He wrote and published in distinct voices for both professional and student readership. In 1826 he instituted the Friday Evening Discourses and subsequently gave children’s lectures at the Royal Institution to great public acclaim. In an inspired, trend-setting move, he befriended the journalist William Jerdan and kept Jerdan’s Literary Gazette regularly supplied with science news from the Royal Institution. In his attention to detail, to systems, to decorum, Faraday was already a Victorian when Princess Victoria herself was a girl playing with her dolls.

The lasting monument of Faraday’s mature years is his Experimental Researches in Electricity (1832–55), forty-five linked papers which lay down the fundamental laws that guide the natural power of electricity, which Faraday considered to be the highest power known to man. The world’s electrical industry is founded on the laws Faraday discovered and tabulated, and, like the Declaration of the Rights of Man, they have been added to but never superseded.

In his old age Faraday’s science became increasingly theoretical, flying away from the solid certainties that he formulated in his mature years. In 1862, when he was effectively retired from science through ill-health and the rapidly increasing pace of change, Faraday was invited to give evidence on the teaching of science to the Public Schools Commission. He accepted the invitation because science education had been the whole purpose of his life; and having emerged as a youth from the bottom of society he felt called in his last years to work to improve education until his breath gave out. But he completely misjudged the narrowness of the Commission’s interest, and misunderstood the coded meaning of the words ‘Public Schools’. Faraday had come to give his views on science education in all schools for the public of Britain; but the Commission was concerned only with Eton, Harrow, Winchester and six other such. Faraday’s anger at being implicated in exclusivity was a late expression of the same passion which had suffused his life, and which drove him across an active career of forty years to reveal, teach and connect.

In writing about Faraday from a background in art history I am only too aware that I may be trying to ride two mettlesome and highly individual horses at the same time. In the 1820s and 1830s, however, the horses pulling the carriage of culture were still at one with each other, still a manageable team, and Faraday held the reins. The divide that began to draw art and science apart in the later nineteenth and twentieth centuries was, then, negotiable. Faraday’s driving role in the development of culture in Britain in the nineteenth century is what this book is about.

CHAPTER 1 ‘The Progress of Genius’

It is clear from the phrasing of his early letters that Michael Faraday spoke at breakneck speed when he wanted to explain something, or to relate his news, fact and reason flooding out of him with excitement and joy in the telling. He lived in London, above a blacksmith’s shop, a friendly boy, with an open face and thick brown curls on a head that was a size too big for his body.1 He was always short, and this made his head seem yet larger; he never grew above about five feet four inches, the height of Napoleon and J.M.W. Turner. His voice had an edge to it, an accent from the streets, and it was perhaps this that betrayed his vulnerability, his apartness, for beyond the accent he was as a boy unable to grip in his mouth words which had a sounding ‘r’ in them: he had what we now call a soft ‘r’. As a result, he could not pronounce his own name. ‘Michael Fawada’, he would say;2 or to avoid misunderstanding or teasing, ‘Mike’.

He had had no formal schooling, just a grounding of reading, writing and arithmetic at a day-school near the smithy in the back premises of 16 Jacob’s Mews, an alley north of Oxford Street. Faraday’s education was blunt – on one occasion when he spoke of his elder brother ‘Wobert’, the schoolmistress gave Robert a halfpenny to buy a cane to thrash the speech defect out of Michael.3 Robert refused to do any such thing, threw the coin over a wall and went home to tell his mother who promptly removed both boys from the school. When not at school, which was most of the time, Michael played with his friends in the street, or at home with his parents, elder brother and sisters. Jacob’s Mews was, and remains – for while the buildings have changed the building line has not – a wide, deep and bright alley, with plenty of room for blacksmithery and anvils to be set out in the yard, and for waiting horses to assemble. There was no academic learning in the family, and no likelihood of it. Michael’s father, James Faraday, had been sick for years, so the family’s financial and social future was insecure. Michael’s mother, Margaret, had however an instinctive feeling that her younger son, her third child, had a special quality, some rare intelligence and intuition in him that she had no word for. ‘My Michael!’, she would say.4

Both his parents were devout. They had been brought up in the strict, non-conformist Sandemanian church in Westmorland, in the north-west of England. They had met and married in it, and arranged their lives according to its lights and guidance. James Faraday was a plain, practical man, the third son in a large smallholding family of Christians from Clapham in north Yorkshire. The allegiance of his parents, Robert and Elizabeth Faraday, had shifted in the volatile atmosphere of religious dissent of the mid-eighteenth century from one sect, the Inghamites, to the Sandemanians. With a historical perspective these changes are minor twists in the grain, but in their period and parish they could lead to anger, betrayal, family division and exclusion. Robert Faraday preached to Inghamite and Sandemanian congregations in Clapham and surrounding villages, and brought his children up to fear God and support the community. His eldest son, Richard, became an innkeeper and grocer, the second, John, a weaver and later a farmer, and the third, James, a blacksmith. Other sons became tailors and leather workers, while the three daughters remained unmarried.5

Michael Faraday’s mother was the sixth child of Michael Hastwell, a farmer, and his wife Betty, of Black Scar Farm at Kaber, Westmorland. Having grown up on a farm, Margaret Hastwell brought rural talents such as threshing, winnowing and cheese- and butter-making to the marriage.6 Like the Faradays, the Hastwells had become Sandemanians, and attended the meeting house in Kirkby Stephen, the small market town on the northern side of the county boundary between Yorkshire and Westmorland. The Clapham and Kirkby Stephen congregations worshipped together from time to time, and it must have been in such sober circumstances that James Faraday and Margaret Hastwell met.7 He took a smithy opposite the King’s Head at Outhgill, five miles south of Kirkby Stephen; she became a maidservant at Deep Gill Farm nearby. They married, aged twenty-five and twenty-two respectively, at Kirkby Stephen parish church in 1786, and their first two children, Elizabeth and Robert, were born in 1787 and 1788.

Outhgill is in Mallerstang, the long, wide, green valley of the River Eden. Coaches travelling to Appleby, Penrith and Carlisle passed along the valley, a northern spur of the only practical route through the hills between Sedbergh to the west and Richmond forty miles over the Pennines to the east. In the year of Robert’s birth, life began to change for James and Margaret. There was a long drought in 1788. It had been a beautiful warm spring, but by the summer they were looking and then praying for rain. Their green Eden grew brown, sheep and cattle died, and the coaches came less often because there was not enough hay for the horses. Then came the autumn frosts, and the worst winter anywhere in England for years.8 For two weeks in December the valley was icy and empty of traffic, and there was no work for the smithy.

The next summer came news of the revolution in France, the mob storming the Bastille, and Louis XVI fleeing Versailles. Then little bands of ill-dressed soldiery marched up and down the valley en route for Carlisle, or Leeds, or London. The prospect of war was frightening, but the presence of poverty was far worse. So, approaching a monumental decision that would change their and their children’s lives, James and Margaret Faraday considered moving to a city. They talked and prayed with the Elders of the church in Kirkby Stephen, made their choice, and prepared to move to London. Margaret was pregnant when they left Outhgill. The slow passage from the north to London was Michael’s first journey. Conceived in Westmorland, he was born in rented rooms near the Elephant and Castle inn, south of the River Thames, on 22 September 1791.

James and Margaret Faraday brought their children up in the exclusive Sandemanian faith in Christ, keeping themselves to themselves, and walking every Sunday to the neat but severe Sandemanian chapel in Paul’s Alley, a dark passage running north from St Paul’s Cathedral, and permanently in shadow. The congregation had an unequal struggle to keep their chapel neat and clean, for Paul’s Alley, as recalled fifty years later, was ‘a narrow, dirty court, surrounded by squalid houses of the poorest of the poor’.9 When questions of temptation, sin, goodness or example arose in the family, they turned to the Bible for an answer. The family Bible (now in the Cuming Museum, Southwark) was their greatest treasure, and in it they recorded their family’s births and deaths. When they opened their Bible, they always found enlightenment and never questioned. Sandemanians followed the lead of the Scottish linen-maker turned divine, Robert Sandeman (1718–71), and dissented from the established churches of England, Wales and Scotland. These they believed were governed against the teachings of the New Testament, were corrupt, and administered as part of the worldly state rather than the kingdom of God.

Sandemanians preached love and hope rather than hellfire and damnation, but it was a tough love. Though they all came together in the aisles to pass the kiss of peace to each other at their services, and washed each other’s feet as a sign of humility, they demanded unanimity in church decisions, which was secured by ‘excluding’ minority dissenters; that is, throwing them out. This was a severe interpretation of 1 Corinthians 1.10, ‘Now I beseech you, brethren, by the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that ye all speak the same thing, and that there be no divisions among you; but that ye be perfectly joined together in the same mind and in the same judgement.’ The teachings of the Bible were literally and strictly true in Sandemanian belief, which preached an intellectual rather than an emotional response to scripture. In the passage from 1 Corinthians, ‘perfectly joined’ was the rub. Any variant interpretation of scripture was forbidden, to the extent that Sandemanians refused to hold communion with any who did not perfectly agree with them.

The Sandemanian faithful dined together in a Love Feast in the chapel’s spotless dining room, or at each other’s houses on Sundays, between morning and afternoon worship, and would not eat the meat of any creature that had been killed by having its neck wrung, as the blood of the creature had to flow at death: this followed instruction in Acts 15.20. Games of chance were also banned, because to Sandemanians the lot was sacred to God, and property, they believed, was common to all. As a small sect, despised or at best dismissed by the established church, they stuck together, intermarried and assisted each other in welfare, housing and employment.10

Sandemanian services, which ran all day, with a break for the Love Feast, followed a strict pattern. They began with a roll-call: all members had to attend on Sundays, or answer for it to the Elders. Study of the Bible took no account of the established church feasts – Christmas, Lent, Easter – but led by the Elders the congregation read the Old Testament through chapter by chapter from Genesis 1 to Malachi 4, and the New Testament from St Matthew 1 to Revelation 22. When they reached the end they started again at the beginning.11 Under the eyes of their Elders, seated in two raised rows of benches in front of them, the congregation conducted their worship as described by the non-conformist historian Walter Wilson in 1810:

After singing a hymn [this was voices only; there were no musical instruments], a member of the church prays; these exercises are repeated three or four times; one of the Elders then reads some chapters from the Old or New Testaments; this is followed by singing; another Elder then prays, and either expounds or preaches for about three-quarters of an hour. Singing follows; and the service is concluded by a short prayer and benediction … In the afternoon, the former part of the service is curtailed; but after the sermon the church is stayed to receive the Lord’s Supper, and contribute to the poor. When this is over, the members of the church are called upon to exercise their gifts by exhortation.12

The Faradays cannot have stayed for long at the Elephant and Castle. During their first few years in London they lived in Gilbert Street, south of Oxford Street, and in 1796 moved across Oxford Street to the back premises of 16 Jacob’s Mews.13 The Mews was remarkable for one thing in particular – it ran behind the Spanish Chapel of the Spanish Embassy, the one place in London in which Roman Catholics could worship legally before the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1828. For Sandemanians this was an extreme juxtaposition of religious practice; no more extreme could they know. In London, as in Westmorland, the Faradays balanced on the edge of poverty. However hard he worked – and his ill-health was a further handicap – James Faraday found it near impossible to support his family, certainly impossible to get anywhere better to live than rented rooms above his smithy.