Полная версия:

Mother of Winter

Voyager

BARBARA HAMBLY

Mother of Winter

Copyright

HarperVoyager An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by Voyager 1997

Copyright © 1996 by Barbara Hambly

Barbara Hambly asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780006482291

Ebook Edition © JANUARY 2014 ISBN: 9780007468997

Version: 2016-12-28

For Robin

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

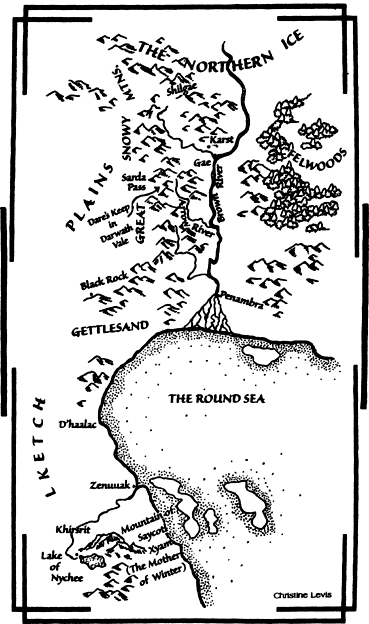

Map

Prologue

Book One: FIMBULTIDE

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

Book Two: THE BLIND KING’S TOMB

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

Keep Reading

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

In the moonstone dawn, the lone rider dismounted at the top of the steps, passed through the black square open eye where the doors would one day be, and halted on the edge of shadowed abyss. The woman who lay on the obsidian plinth in the chasm’s midst knew by the shape of his shoulders and back, by the way he carried his head, who he was; there was in any case only one person he could be. The wind that brought the smell of the glaciers down to her funneled past him through the passageway and carried on it the stench of blood.

When he stepped clear of the gate’s collected gloom, she saw he was covered with it, as if he had lain down in a butcher’s shambles. Some of it she knew was his, all mixed with the nitrous grease of torch smoke; there was also mud on his bare left forearm where he had fallen or been thrown from his horse, and on his bare knees above his boot tops, as if he had knelt in gore-soaked earth—to raise someone in his arms, perhaps.

The great clean-hewed pit of the foundation lay between them, deep as the cliffs that surrounded the Vale, and filled with the night’s last shade. The plinth that rose through it, nearly to the level of the ground, was circled by half-made levels and support pillars like the greatest trees in some primordial iron forest, dwarfed to fragility by the chasm’s sheer size. The machines that fused the black stone walls, insectile monsters of crystal and meteor iron, stood quiescent on platforms in the scaffolding; smaller slave-crystals and drones floated in the air between like exhausted stars, and here and there great sheets of wyr-web flashed softly in the nacreous light. Where the stairways and catwalks joined and crossed between the greater platforms, sleeping figures could be seen, lying where they had collapsed within the rings and spheres of silver dust, dried blood, smoke and light that trailed off the fragile plank flooring to float like sea-wrack on the air.

He looked down to meet the woman’s eyes.

Depleted by last night’s Great Spell, she propped herself up with her hands and coughed, feeling twice her sixty years. As the man picked his way across the spiderweb lines of bamboo and planking, descended ladders and stepped over gaps that fell away into a thousand feet of gloom, she saw that he, too, moved carefully, holding to the ropes and stopping now and then to stand half bowed over, gathering strength.

“It’s all right,” she said, when he looked down from a ladder at the intricate patterns woven on the plinth’s circular top. “The spells are accomplished, such as they are. Stay between those two lines and all will be well.”

He was a respecter of such things. Not everyone was these days. He looked around him again, and she wondered if, from the plinth, he could see what she saw: the whole of the future edifice called forth in those ghostly traceries, as if the fortress already existed, wrought of starlight and future time.

Every Rune, every circle, every sigil and smoke-trace had been placed individually, by her hand or the hands of those who slept all around her huddled in the lee of the Foci, broken by what they had done.

And to no avail, she thought. To no avail.

She asked him, “Are they dead?”

He nodded.

“All of them?”

“All.”

It was not the worst thing she had ever borne, but in some ways more painful than the knowledge that the world’s end was coming sooner than anyone had reckoned. She had loved many of those who died last night.

“You should have asked our help.”

He was unshaven under the filth; even the ends of his long hair, by which he was nicknamed at Court, were tipped with grue. “It was the only chance you had, of raising the power to do this.” He had a voice like gravel and clinkers in an iron pan. “The locking point of sun, moon, and stars, you said The time of greatest power.” He swallowed, fighting pain. “It was worth what it cost.”

She folded her arms across her breasts, bare beneath the midnight wool of her cloak. The morning was very cold. Below her the murmur of water was loud where springs had been broached in the rock. The smell of wet earth breathed up around them. Far down the Vale where the trees grew thick at the head of the pass, birds were waking.

“No,” she said. “For we failed. We put forth all our strength, and all our strength was not enough. And all this—” The movement of her hand took in the half-raised walls, the silent machines, the chasm of foundation, the whisper of water and of that half-seen skeleton of light. “—all this will pass away, and leave us with nothing.”

Her head bowed. She hadn’t wept for years, not since one night when she’d seen a truth too appalling to be contemplated in the color of the stars. But her grief was a leaden darkness, seeming to pull them both down into the beginning of an endless fall. “I’m sorry.”

CHAPTER ONE

“Do you see it?” Gil Patterson’s voice was no louder than the scratch of withered vines on the stained sandstone wall. Melding with the shadows was second nature to her by now. The courtyard before them was empty and still, marble pavement obscured by lichen and mud, and a small forest of sycamore suckers half concealed the fire-black ruins of the hall, but she could have sworn that something had moved. “Feel it?”

She edged forward a fraction of an inch, the better to see, taking care to remain still within the ruined peristyle’s gloom. “What is it?”

The possibility of ghosts crossed her mind.

The five years that had passed since eight thousand people died in this place in a single night had been hard ones, but some of their spirits might linger.

“I haven’t the smallest idea, my dear.”

She hadn’t heard him return to her from his investigation of the building’s outer court: he was a silent-moving man. Pitched for her hearing alone, his voice was of a curious velvety roughness, like dark bronze broken by time. In the shadows of the crumbling wall, and the deeper concealment of his hood, his blue eyes seemed very bright.

“But there is something.”

“Oh, yes.” Ingold Inglorion, Archmage of the wizards of the West, had a way of listening that seemed to touch everything in the charred and sodden waste of the city around them, living and dead. “I suspect,” he added, in a murmur that seemed more within her mind than outside of it, “that it has stalked us since we passed the city walls.”

He made a sign with his hand—small, but five years’ travel with him in quest of books and objects of magic among the ruins of cities populated only by bones and ghouls had taught her to see those signs. Gil was as oblivious to magic as she was to ghosts—or fairies or UFOs for that matter, she would have added—but she could read the summons of a cloaking spell, and she knew that Ingold’s cloaking spells were more substantial than most people’s houses.

Thus what happened took her completely by surprise.

The court was a large one. Thousands had taken refuge in the house to which it belonged, in the fond hope that stout walls and plenty of torchlight would prevent the incursion of those things called only Dark Ones. Their skulls peered lugubriously from beneath dangling curtains of colorless vines, white blurs in shadow. It was close to noon, and the silver vapors from the city’s slime-filled canals were beginning to burn off, color struggling back to the red of fallen porphyry pillars, the brave blues and gilts of tile. More than half the court lay under a leprous blanket of the fat white juiceless fungus that surviving humans called slunch, and it was the slunch that drew Gil’s attention now.

Ingold was still motionless, listening intently in the zebra shadows of the blown-out colonnade as Gil crossed to the edge of the stuff. “It isn’t just me, is it?” Her soft voice fell harsh as a blacksmith’s hammer in the unnatural hush. “It’s getting worse as we get farther south.” As Gil knelt to study the tracks that quilted the clay soil all along the edges of the slunch, Ingold’s instruction—and that of her friend the Icefalcon—rang half-conscious warning bells in her mind. What the hell had that wolverine been trying to do? Run sideways? Eat its own tail? And that rabbit—if those were rabbit tracks …? That had to be the mark of something caught in its fur, but …

“It couldn’t have anything to do with what we’re looking for, could it?” A stray breath lifted the long tendrils of her hair, escaping like dark smoke from the braid jammed under her close-fitting fur cap. “You said Maia didn’t know what it was or what it did. Was there anything weird about the animals around Penambra before the Dark came?”

“Not that I ever heard.” Ingold was turning his head as he spoke, listening as much as watching. He’d put back the hood of his heavy brown mantle, and his white hair, long and tatty from weeks of journeying, flickered in the gray air. He’d trimmed his beard with his knife a couple of nights ago, and resembled St. Anthony after ten rounds with demons in the wilderness.

Not, thought Gil, that anyone in this universe but herself—and Ingold, because she’d told him—knew who St. Anthony was. Maia of Thran, Bishop of Renweth, erstwhile Bishop of Penambra and owner of the palace they sought, had told her tales of analogous holy hermits who’d had similar problems.

Unprepossessing, she thought, to anyone who hadn’t seen him in action. Almost invisible, unless he wished to be seen.

“And in any case we might as easily be dealing with a factor of time rather than distance.” Ingold held up his six-foot walking staff in his blue-mittened left hand, but his right never strayed far from the hilt of the sword at his side. “It’s been … Behind you!”

He was turning as he yelled, and his cry was the only reason the thing didn’t take Gil full in the back like a bobcat fastening on a deer. She was drawing her own sword, still on her knees but cutting as she whirled, and aware at the same moment of Ingold drawing, stepping in, slashing. Ripping weight collided with Gil’s upper arm and she had a terrible impression of a short-snouted animal face, of teeth thrusting out of a lifted mass of wrinkles, of something very wrong with the eyes …

Pain and cold sliced her right cheek low on the jawbone. She’d already dropped the sword, pulled her dagger; she slit and ripped and felt blood and intestines gush hotly over her hand. The thing didn’t flinch. Long arms like an ape’s wrapped around her shoulders, claws cutting through her sheepskin coat. It bit again at her face, going for her eyes, its own back and spine wide open. Gil cut hard and straight across them with seven-inch steel that could shave the hair off a man’s arm. The teeth spasmed and snapped, the smell of blood clogging her nostrils. Buzzing dizziness filled her. She thought she’d been submerged miles deep in dry, living gray sand.

“Gil!” The voice was familiar but far-off, a fly on a ceiling miles above her head. She’d heard it in dreams, maybe …

Her face hurt. The lips of the wound in her cheek were freezing now against the heat of her blood. For some reason she had the impression she was waking up in her own bed in the fortress Keep of Dare, far away in the Vale of Renweth.

“What time is it?” she asked. The pain redoubled and she remembered. Her head ached.

“Lie still.” He bent over her, lined face pallid with shock. There was blood on the sleeves of his mantle, on the blackish bison fur of the surcoat he wore over that. She felt his fingers probe gently at her cheek and jaw. He’d taken off his mittens, and his flesh was startlingly warm. The smell of the blood almost made her faint again. “Are you all right?”

“Yeah.” Her lips felt puffy, the side of her face a balloon of air. She put up her hand and remembered, tore off her sodden glove, brushed her lips, then the corner of her right eye with her fingertips. The wounds were along her cheekbone and jaw, sticky with blood and slobber. “What was that thing?”

“Lie still a little more.” Ingold unslung the pack from his shoulders and dug in it with swift hands. “Then you can have a look.”

All the while he was daubing a dressing of herb and willow bark on the wounds, stitching them and applying linen and plaster—braiding in the spells of healing, of resistance to infection and shock—Gil was conscious of him listening, watching, casting again the unseen net of his awareness over the landscape that lay beyond the courtyard wall. Once he stood up, quickly, catching up the sword that lay drawn on the muddy marble at his side, but whatever it was that had stirred the slunch was still then and made no further move.

He knelt again. “Do you think you can sit up?”

“Depends on what kind of reward you offer me.”

His grin was quick and shy as he put a hand under her arm.

Dizziness came and went in a long hot gray wave. She didn’t want him to think her weak, so she didn’t cling to him as she wanted to, seeking the familiar comfort of his warmth.

She breathed a couple of times, hard, then said, “I’m fine. What the hell is it?”

“I was hoping you might be able to tell me.”

“You’re joking!”

The wizard glanced at the carcass—the short bulldog muzzle, the projecting chisel teeth, the body a lumpy ball of fat from which four thick-scaled, ropy legs projected—and made a small shrug. “You’ve identified many creatures in our world—the mammoths, the bison, the horrible-birds, and even the dooic—as analogous to those things that lived in your own universe long ago. I hoped you would have some lore concerning this.”

Gil looked down at it again. Something in the shape of the flat ears, of the fat, naked cone of the tail—something about the smell of it—repelled her, not with alienness, but with a vile sense of the half familiar. She touched the spidery hands at the ends of the stalky brown limbs. It had claws like razors.

What the hell did it remind her of?

Ingold pried open the bloody jaws. “There,” he said softly. “Look.” On the outsides of the gums, upper and lower, were dark, purplish, collapsed sacs of skin; Gil shook her head, uncomprehending. “How do you feel?”

“Okay. A little light-headed.”

He felt her hands again and her wrists, shifting his fingers a little to read the different depths of pulse. For all his unobvious strength, he had the gentlest touch of anyone she had ever known. Then he looked back down at the creature. “It’s a thing of the cold,” he said at last. “Down from the north, perhaps? Look at the fur and the way the body fat is distributed. I’ve never encountered an arctic animal with poison sacs—never a mammal with them at all, in fact.”

He shook his head, turning the hook-taloned fingers this way and that, touching the flat, fleshy ears. “I’ve put a general spell against poisons on you, which should neutralize the effects, but let me know at once if you feel in the least bit dizzy or short of breath.”

Gil nodded, feeling both slightly dizzy and short of breath, but nothing she hadn’t felt after bad training sessions with the Guards of Gae, especially toward the end of winter when rations were slim. That was something else, in the five years since the fall of Darwath, that she’d gotten used to.

Leaving her on the marble bench, with its carvings of pheasants and peafowl and flowers that had not blossomed here in ten summers, Ingold bundled the horrible kill into one of the hempen sacks he habitually carried, and hung the thing from the branch of a sycamore dying at the edge of the slunch, wreathed in such spells as would keep rats and carrion feeders at bay until they could collect it on their outward journey. Coming back to her, he sat on the bench at her side and folded her in his arms. She rested her head on his shoulder for a time, breathing in the rough pungence of his robes and the scent of the flesh beneath, wanting only to stay there in his arms, unhurried, forever.

It seemed to her sometimes, despite the forty years’ difference in their ages, that this was all she had ever wanted.

“Can you go on?” he asked at length. Carefully, he kissed the unswollen side of her mouth. “We can wait a little.”

“Let’s go.” She sat up, putting aside the comfort of his strength with regret. There was time for that later. She wanted nothing more now than to find what they had come to Penambra to find and get the hell out of town.

“Maia only saw the Cylinder once.” Ingold scrambled nimbly ahead of her through the gotch-eyed doorway of the colonnade and up over a vast rubble heap of charred beams, shattered roof tiles, pulped woodwork, and broken stone welded together by a hardened soak of ruined plaster. Mustard-colored lichen crusted it, and a black tangle of all-devouring vines in which patches of slunch grew like dirty mattresses dropped from the sky. The broken statue of a female saint regarded them sadly from the mess: Gil automatically identified her by the boat, the rose, and the empty cradle as St Thyella of lifers.

“Maia was always a scholar, and he knew that people were using fire as a weapon against the Dark Ones. Whole neighborhoods gathered wherever they felt the walls would hold—though they were usually wrong about that—and burn whatever they could find, hoping a bulwark of light would serve should bulwarks of stone fail. They were frequently wrong about that as well.”

Gil said nothing. She remembered her first sight of the Dark. Remembered the fleeing, uncomprehending mobs, naked and jolted from sleep, men and women falling and dying as the blackness rolled over them. Remembered the thin, directionless wind, the acid-blood smell of the predators, and the way fluid and matter would rain over her when she slashed the amorphous, floating things in half with her sword.

They picked their way off the corpse of the building into a smaller court, its wooden structures only a black frieze of ruin buried in weeds. On a fallen keystone the circled cross of the Straight Faith was incised. “Asimov wrote a story like that,” she said.

“ ‘Nightfall.’ “ Ingold paused to smile back at her. “Yes.”

In addition to her historical studies in the archives of the Keep of Dare, Gil had gained quite a reputation among the Guards as a spinner of tales, passing along to them recycled Kipling and Dickens, Austen and Heinlein, Doyle and Heyer and Coles, to ease the long Erebus of winter nights.

“And it’s true,” the old man went on. “People burned whatever they could find and spent the hours of day hunting for more.” His voice was grim and sad—those had been, Gil understood, people he knew. Unlike many wizards, who tended to be recluses at heart, Ingold was genuinely gregarious. He’d had dozens of friends in Gae, the northern capital of the Realm of Darwath, and here in Penambra: families, scholars, a world of drinking buddies whom Gil had never met. By the time she came to this universe, most were dead.

Three years ago she had gone with Ingold to Gae, searching for old books and objects of magic in the ruins. Among the shambling, pitiful ghouls who still haunted the broken cities, he recognized a man he had known. Ingold had tried to tell him that the Dark Ones whose destruction had broken his mind were gone and would come no more, and had narrowly missed being carved up with rusty knives and clamshells for his pains.

“I can’t say I blame them for that.”

“No,” he murmured. “One can’t.” He stopped on the edge of a great bed of slunch that, starting within the ruins of the episcopal palace, had spread out through its windows and across most of the terrace that fronted the sunken, scummy chain of puddles that had been Penambra’s Grand Canal. “But the fact remains that a great deal was lost.” Motion in the slunch made him poke at it with the end of his staff, and a hard-shelled thing like a great yellow cockroach lumbered from between the pasty folds and scurried toward the palace doors. Ingold had a pottery jar out of his bag in seconds and dove for the insect, swift and neat. The roach turned, hissing and flaring misshapen wings; Ingold caught it midair in the jar and slapped the vessel mouth down upon the pavement with the thing clattering and scraping inside. It had flown straight at his eyes.

“Most curious.” He slipped a square of card—and then the jar’s broad wax stopper—underneath, and wrapped a cloth over the top to seal it. “Are you well, my dear?” For Gil had knelt beside the slunch, overwhelmed with sudden weariness and stabbed by a hunger such as she had not known for months. She broke off a piece of the slunch, like the cold detached cartilage of a severed ear, and turned it over in her fingers, wondering if there were any way it could be cooked and eaten.

Then she shook her head, for there was a strange, metallic smell behind the stuff’s vague sweetness—not to mention the roach. She threw the bit back into the main mass. “Fine,” she said.