Полная версия:

Empires of the Monsoon

EMPIRES OF

THE MONSOON

A History of the Indian Oceanand its Invaders

RICHARD HALL

COPYRIGHT

William Collins

An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1996

Copyright © Richard Hall 1996

Part title decoration from ‘The Fleet of Vasco da Gama’ illustrated in The Portuguese in India, Vol. 1, by Frederick Danvers

Richard Hall asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780006380832

Ebook Edition © APRIL 2016 ISBN: 9780007547043

Version: 2018–10–09

DEDICATION

Dedicated to the memory of Harry A. Logan Jr of Warren, Pennsylvania

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Maps

Foreword

A Note on Spellings

PART ONE: A World Apart

1. Wonders of India, Treasures of China

2. Lure of the African Shore

3. The Mystery of the Waqwaqs

4. Islam Rules in the Land of Zanj

5. On the Silk Route to Cathay

6. A Princess for King Arghon

7. The Wandering Sheikh Goes South

8. Adventures in India and China

9. Armadas of the Three-Jewel Eunuch

10. Ma Huan and the House of God

11. The King of the African Castle

PART TWO: The Cannons of Christendom

12. Prince Henry’s Far Horizons

13. Commanding the Guinea Coast

14. The Shape of the Indies

15. The Lust for Pepper, the Hunt for Prester John

16. The Spy Who Never Came Home

17. Kings and Gods in the City of Victory

18. Da Gama Enters the Tropical Ocean

19. A First Sight of India

20. The Fateful Pride of Ibn Majid

21. Sounds of Europe’s Rage

22. The Vengeance of da Gama

23. The Viceroy in East Africa

24. Defeating the Ottoman Turks at Diu

25. The Great Afonso de Albuquerque

26. Ventures into the African Interior

27. From Massawa to the Mountains

28. At War with the Left-handed Invader

29. Taking Bible and Sword to Monomotapa

30. Turkish Adventurers, Hungry Cannibals

31. The Renegade Sultan

32. The Lost Pride of Lusitania

33. Calvinists, Colonists and Pirates

34. Ethiopia and the Hopes of Rome

35. The Great Siege of Fort Jesus

36. Western Aims, Eastern Influences

PART THREE: An Enforced Tutelage

37. Settlers on India’s Southern Approaches

38. The Seas beyond Napoleon’s Reach

39. The French Redoubt and the Isle of Slaves

40. ‘Literally a Blank in Geography’

41. Two Ways with the Spoils of War

42. The Sultan and the King’s Navy

43. Stepping Back from East Africa

44. The Americans Discover Zanzibar

45. Looking Westwards from the Raj

46. Portents of Change in the ‘English Lake’

47. In the Footsteps of a Missionary

48. Warriors, Hunters and Traders

49. A Proclamation at the Custom House

50. Meeting the Lords of the Interior

51. The Failure of a Philanthropic Scotsman

52. Imperialism Abhors a Vacuum

53. Bismarck and the Gesellschaft

54. Africa Hears the Maxims of Faith and War

55. From Sultan’s Island to Settlers’ Highlands

Epilogue

Index

Index of Personal Names

Acknowledgements

Further Reading

Commentary

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

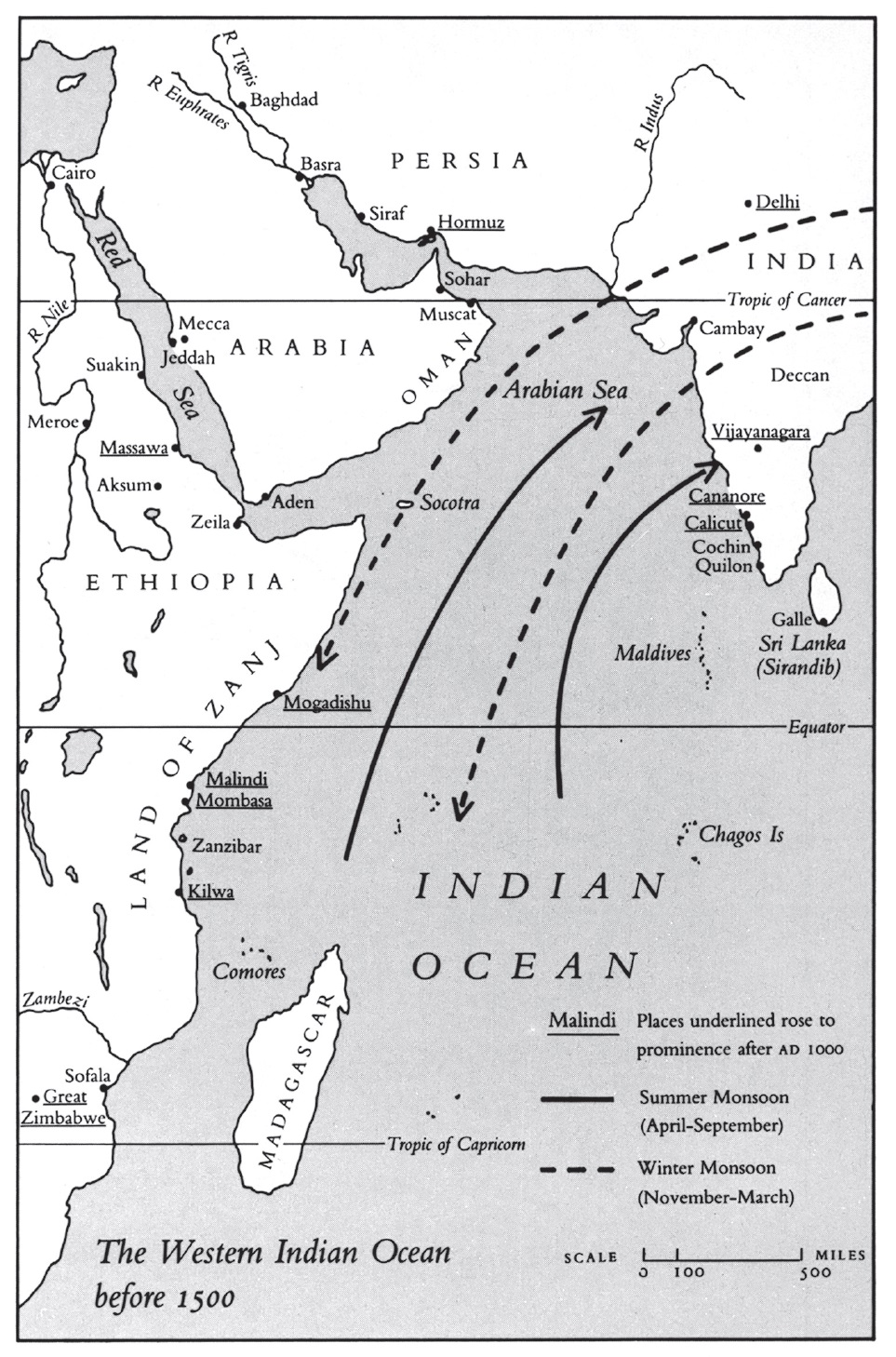

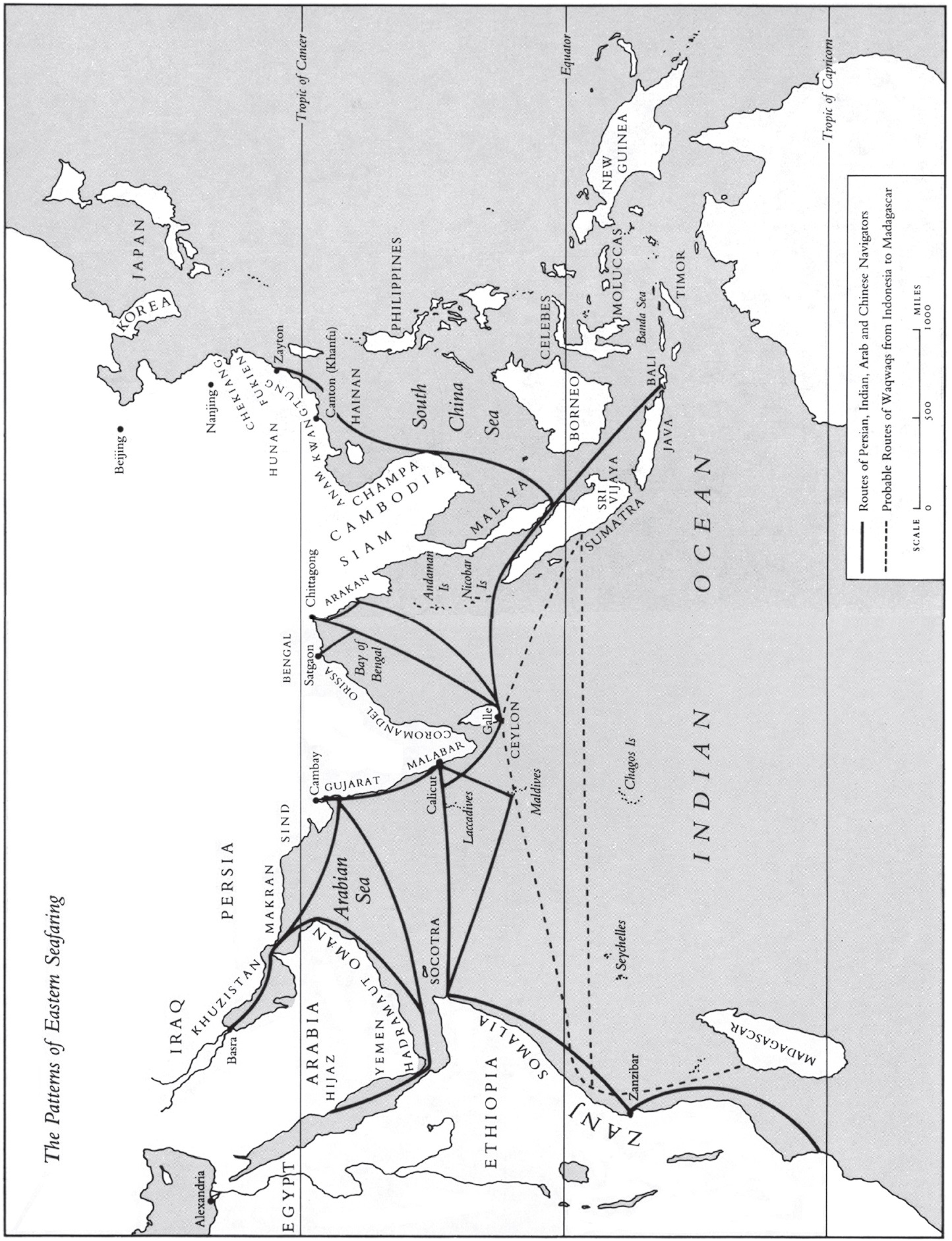

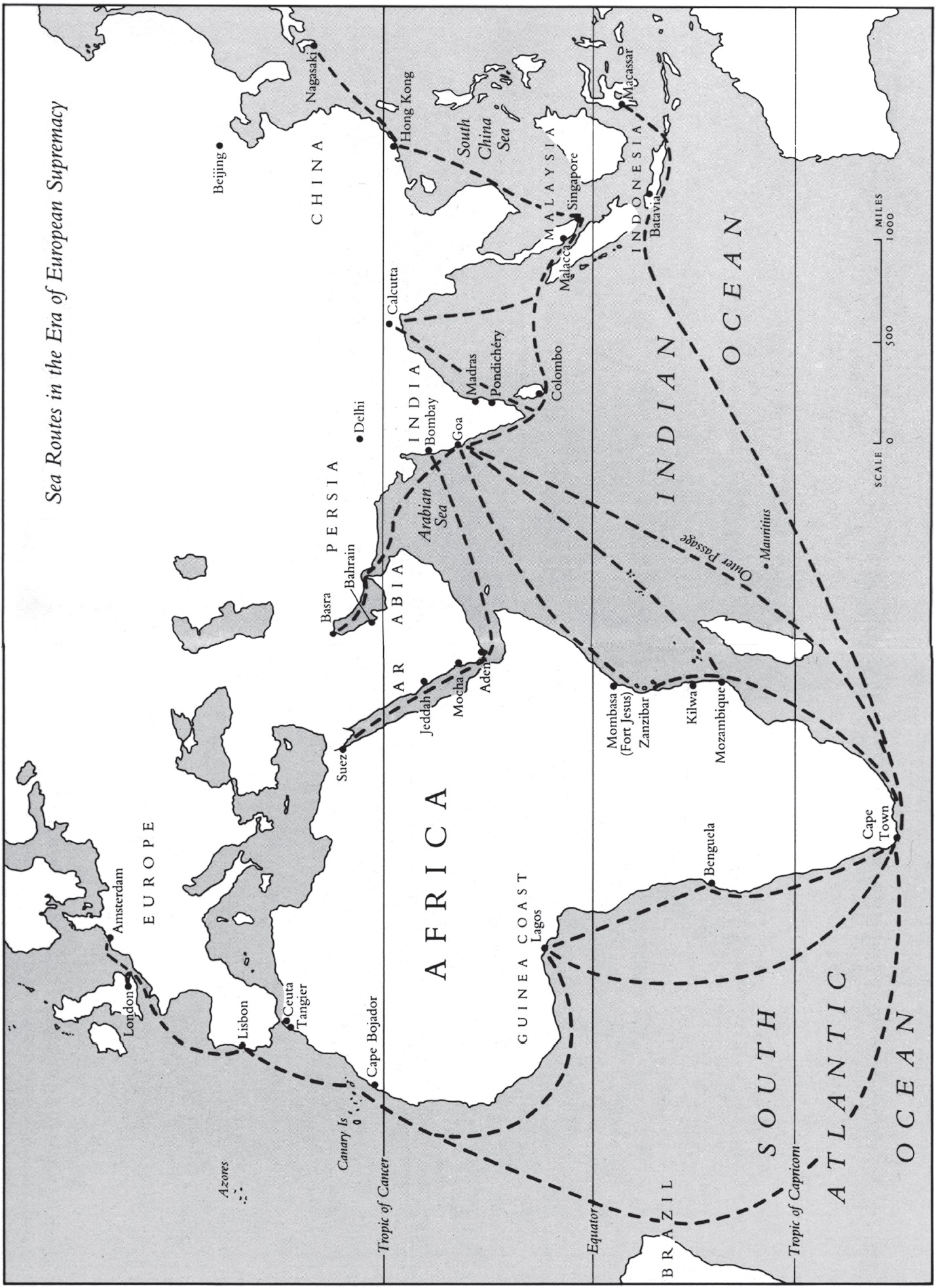

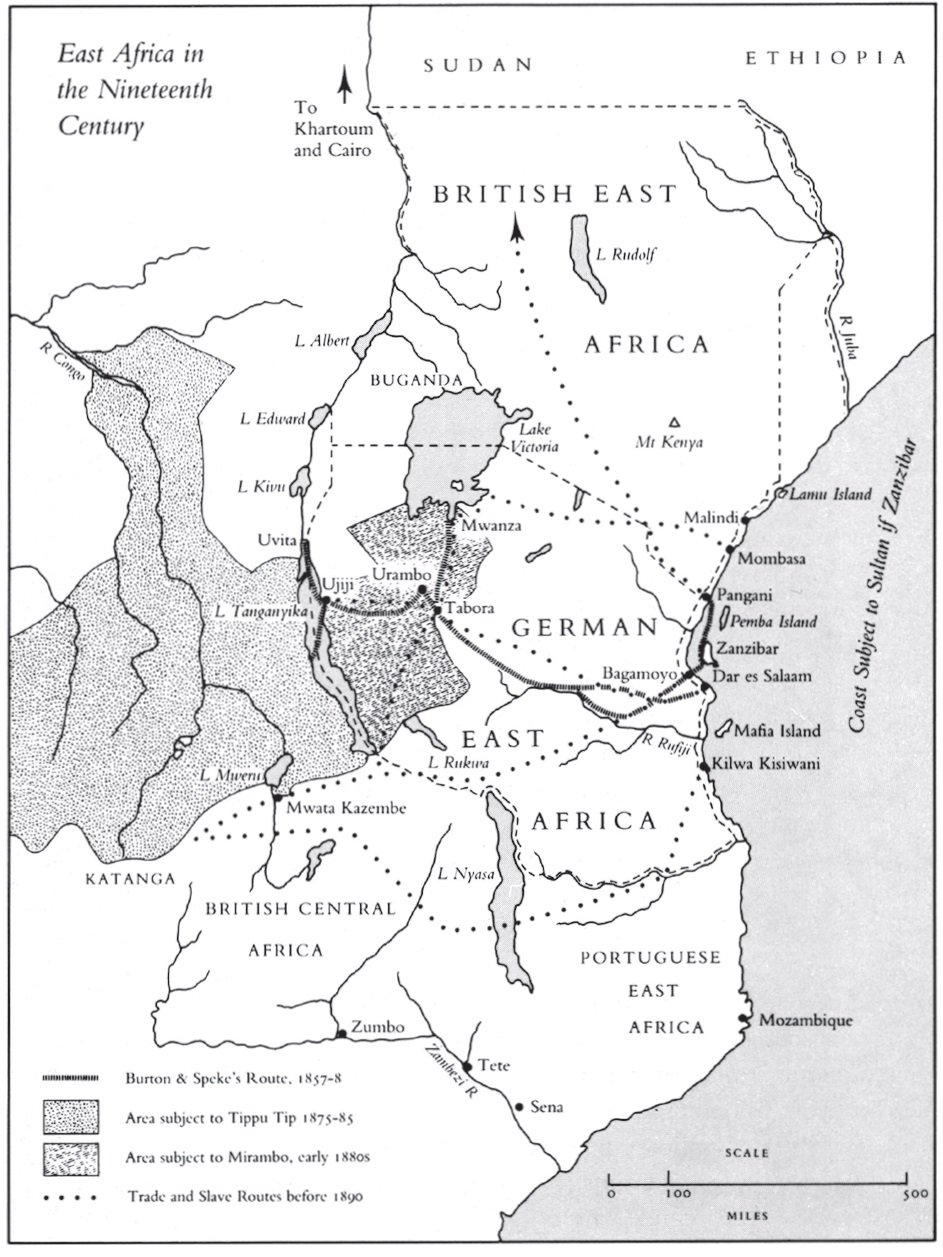

MAPS

Maps by Leslie Robinson

FOREWORD

Turn a map of the world upside down and the Indian Ocean can be seen as a vast, irregularly-shaped bowl, bounded by the shorelines of Africa and Asia, the islands of Indonesia, and the coast of Western Australia.1 Unlike the Atlantic and Pacific, merging at their extremes into the polar seas, this is an entirely tropical ocean; to mention it calls up a vision of palm-fringed islands and lagoons where rainbow-hued fish dart amid the coral. That is the tourist-brochure image, but behind it lies the Indian Ocean of history – a centre of human progress, a great arena in which many races have mingled, fought and traded for thousands of years.

The earliest civilizations, in Egypt and the valley of the Tigris and Euphrates, had direct access to the Indian Ocean by way of the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf. At the hub, stretching towards the equator, lay the Indian sub-continent, itself the site of ancient cultures in the Indus valley. Since long before the time of Alexander the Great, travellers had brought back tales of the rich and voluptuous East. The emperor Trajan, arriving triumphantly at the Persian Gulf in A.D. 116, and watching mariners set sail for India, had mourned that he was too old to make the voyage and gaze upon its wonders.2

For almost a thousand years after the fall of the Roman empire the western side of the Indian Ocean, the focus of this book, was as much an entity as the Mediterranean, surpassing it in wealth and power. The arts and scholarship flourished there, in cities to which merchants came from all corners of the known world. There was also much turmoil, as conquering armies spawned in the remote parts of Asia swept down to overthrow old empires and impose new dynasties.

The lives of ordinary people, however, were always ruled more by nature than by great events, by the perpetual monsoons rather than by ephemeral monarchies. The word ‘monsoon’ comes from the Arabic mawsim, ‘season’, and ever since sailors had dared to venture on voyages across the open seas these seasonal winds had borne their ships between India and its distant neighbours. For six months they blow one way, then in the reverse direction during the other half of the year. The summer monsoon, coming from East Africa and the southern seas, is pulled eastwards by the rotation of the earth after passing the equator, so that it sweeps across India and up through the Bay of Bengal. Winds are fiercest between June and August.

The sea-captains of old might not understand why the monsoons happened (how colder air was being sucked northwards over the ocean in summer towards the hot lands of Asia, then southwards from the Himalayas and the Indian plains in winter); for them it was sufficient that the winds came on time, year in and year out, to fill their sails. For the farmers of India it was likewise enough to know that the summer monsoon would bring them rain.3 However, on sea and land, the monsoon was always feared in its times of fury, when no vessel dared set out, when floods swept away villages, and cyclones left devastation.

It might be argued that the inescapable rhythm of this climate induced a certain fatalism among the Indian Ocean peoples. Yet the monsoon has also long been recognized as one of nature’s most benign phenomena – ‘a subject worthy of the thoughts of the greatest philosophers’, in the words of John Ray, a seventeenth-century English scientist.4

Until the ‘Age of Discovery’, there had been a thousand years of almost total ignorance in Europe about the Indian Ocean and the lands encompassing it. Once, during the heyday of the Roman empire, a flourishing trade had existed with the East, conducted mainly by Greek mariners who had learned how to use the monsoons.5 They brought back jewels, cinnamon, perfumes and incense, as well as silks and diaphanous Indian cloth much sought after by the women of Rome. But with the collapse of classical civilization in Europe, all the knowledge acquired by the Greeks was lost to Europeans.6

When medieval Europe started looking for a new route to India, to outflank Islam’s barrier across the Middle East, its navigators were long thwarted by the great bulk of Africa, until the Portuguese finally rounded the Cape of Good Hope. Vasco da Gama’s voyage to India and back in 1497–99 was by far the longest sea journey ever undertaken by Europeans.

This book shows how the European presence from the sixteenth century onwards changed Indian Ocean life irrevocably. Thriving kingdoms were subdued and former relationships between religions and races thrown into disarray. With the advent of western capitalism, ancient patterns of trade soon became as extinct as the dodo (which Dutch sailors had unceremoniously wiped out on the island of Mauritius). Yet although the guns of Europe could create new empires in the East, the populations there were too great to be held down permanently. What happened in the Americas was never going to be repeated in Asia. The record of European intervention and the response to it is made up of violence, depravity and courage.

Through thousands of years of change in the Indian Ocean arena, the African giant forming its long western flank was rarely anything other than a mute bystander. Its interior was terra incognita, its peoples excluded from fruitful dealings with the rest of the world. Since the eighth century, Africa’s contact with the Indian Ocean had come under the sway of scores of Arab-ruled trading ports, strung along two thousand miles of coastline from Somalia to beyond the Zambezi river delta. These settlements looked to the sea; the interior of the continent interested them only as a source of ivory, gold, leopard-skins and slaves. For three hundred years after the arrival of the Europeans, little happened to alter that pattern.

But Africa south of the equator has been twice liberated since the mid-nineteenth century: first from its isolation, then from a colonialism which, although short-lived, seemed to have forged unbreakable bonds with the North, with Europe. Now the monsoons of history are blowing afresh, as the balance of world power swings back to the East. The start of the twenty-first century is seen as ushering in a new ‘Age of Asia’, in which the natural unity of the Indian Ocean can once more assert itself. This is the arena where the full potential of the peoples of sub-Saharan Africa will be put to the test.

A NOTE ON SPELLINGS

Where versions of names converted from non-roman scripts are widely recognized, they are adhered to: for instance, the spelling Mecca is used rather than Makkah, even though the latter is more exact. Likewise, the renowned sultan of Zanzibar in the second half of the nineteenth century should strictly be entitled al-Sayyid Sa’id, but his name was always ‘Europeanised’ as Seyyid Said. For other transliterations from Arabic the Encyclopaedia of Islam is generally followed, but without diacritical marks. With Chinese names the modern pinyin romanization has been adopted – so that the admiral formerly known in English as Cheng Ho appears as Zheng He. Most prefixes to root words in African languages are omitted for simplicity’s sake.

Portuguese monarchs and princes are, in the main, referred to by the familiar anglicized versions of their names. Lesser beings are left in the original.

Geographical terms accord as far as possible with those in use at the times being written about. Thus Ceylon describes the island which became Sri Lanka in 1972. There is often a wide divergence between early European attempts at Indian names and those employed today; an example is Calicut, the once renowned port which appears on modern maps as Kozhikode.

ONE

Wonders of India, Treasures of China

Unmindful of the dangers of ambition and worldly greed, I resolved to set out on another voyage. I provided myself with a great store of goods and, after taking them down the Tigris, set out from Basra, with a band of honest merchants.

—Sinbad, starting his third journey, in The Thousand and One Nights

A THOUSAND YEARS AGO, a Persian sea-captain retired to write his memoirs. They made him famous in his day, although only a single copy of the text now survives, in a mosque in Istanbul. Captain Buzurg ibn Shahriyar called his book The Wonders of India, yet he did not limit himself to describing the civilization of the Hindus. Buzurg presented his readers with a kaleidoscope of life all round the shores of the tropical ocean across which he had sailed throughout his career. His spontaneity brings back to life the people of his time far better than any scholarly reconstruction could achieve: passengers terrified in a storm-tossed ship, merchants angry at being cheated, young men in love, proud monarchs staring down from bejewelled thrones.

He included, for amusement’s sake, many fantastical anecdotes about mermaids, giant snakes which swallowed elephants, two-headed snakes whose bite killed so quickly ‘there is not even time to wink’, and women of immense sexual prowess. ‘Buzurg’ was just a nickname, meaning ‘big’, and he might well have earned it through his love of tall stories, rather than by being large in physique. However, his avowed aim was to take his audience on a tour – entertaining yet instructive – through many lands. Despite similarities between The Wonders of India and The Thousand and One Nights, the distinction is that Sinbad was a fictional hero, while much that Buzurg wrote stands up to historical scrutiny.

References to known characters and recorded events show that he was working on his memoirs in about the year 950 (A.H. 341 by his own Islamic calendar). He lived in the port of Siraf, at the southern end of the Persian Gulf, from whose narrow straits the Indian Ocean opened out like a fan. Just as the Romans had called the Mediterranean mare nostrum (‘our sea’) so the Indian Ocean was for Buzurg and his contemporaries an extension of the Bilad al-Islam, the World of Islam.

Siraf had 300,000 inhabitants, but was hemmed in by mountains. The city became like a cauldron in the summer months, and one of Buzurg’s contemporaries called it the hottest place in Persia. It was also one of the richest. Fountains played constantly in the courtyards of the wealthier merchant families, and after dark the light from scented oil, burning in gilded chandeliers, shone down on divans draped with silk and velvet. Walls of the tall houses were panelled with teak from India, and mangrove poles from Africa supported the flat roofs. The biggest buildings in Siraf were the governor’s palace and the great mosque. Ships in the harbour brought cargoes from many lands, including China; smaller craft took goods further up the Gulf to Basra, where ocean-going vessels often could not unload because of the silt brought down by the Tigris river.1

Even Siraf could not pretend to compete in luxury or grandeur with Basra – still less with Baghdad, capital of the caliphs. The colossal palaces beside the Tigris, their domes supported on columns of transluscent alabaster, were the wonder of the Arab world. The historian al-Muqaddasi, a contemporary of Buzurg, extolled its splendour: ‘Baghdad, in the heart of Islam, is the city of well-being; in it are the talents of which men speak, and elegance and courtesy. Its winds are balmy and its science penetrating. In it are to be found the best of everything and all that is beautiful … All hearts belong to it, and all wars are against it.’

Although the power of the caliphs, the Commanders of the Faithful, had been fractured by dynastic rivalries, Baghdad still controlled an empire stretching from India to Egypt. Three centuries after its founding, the faith of Islam embraced many more people and far greater territories than Christianity, which was already near the end of its first thousand years. Buzurg’s writings open a window on to this moment, at the ushering in of a new millennium during which the two religions were to be in almost ceaseless conflict.

The cities of Iraq, Persia and India would have astounded the impoverished peoples in the West, had they been aware of them; but Europe’s horizons still scarcely reached beyond the uncertain boundaries of its semi-literate warlords. Western Europe lay on the outer fringes of world civilization, whereas Baghdad could boast of being at its centre, with Constantinople the only rival. The unifying concepts of ‘Europe’ and ‘Christendom’ had yet to take root. Half-pagan, half-Christian raiders from Scandinavia were still able to cause havoc almost everywhere.

Some remnants of classical learning had survived within the walls of European monasteries, but these could not compare with the libraries of Arab scholars, who by now had almost all the great works of ancient Greece available to them in translation. These writings would have been more readily available to Buzurg, a sea-captain in Persia, than to the most learned of Christian bishops in Europe.

Outside the boundaries of Islam, which extended along the coast of North Africa and into Spain, direct contacts between East and West were few. Almost the only European Christians who travelled further than Italy were traders going surreptitiously to Alexandria, pilgrims striving to reach Jerusalem, and young girls and boys sold into slavery. The girls were destined to serve in the Arab harems, in company with female slaves from Ethiopia and the remote African lands south of the Red Sea. The boys were eunuchs, castrated at a notorious assembly point at Verdun in France, taken over the Pyrenees into Spain, and shipped from there to the Indian Ocean countries in the charge of Jewish merchants known as the Radhaniyya (‘those who know the route’).

However, there had been a brief time, at the start of the ninth century, when a positive understanding between Christian Europe and Islam seemed possible. Despite their remoteness from one another, the caliph Harun al-Rashid and Charlemagne, Holy Roman Emperor, several times exchanged ambassadors, bearing messages about a never-fulfilled Arab plan for a concerted war to capture Constantinople, the capital of Byzantium. (The exchange of envoys is mentioned only by Charlemagne’s scribes; Islamic chroniclers probably thought it unworthy of note, since Harun received ambassadors in Baghdad from so many lands and despatched his own in every direction.) In his youth Harun had besieged Constantinople, and now wanted to exploit the divisions between the Catholics and the eastern Christians. He only took this course after vainly despatching envoys to the Byzantine emperor, Constantine VI, urging him to convert to Islam.

The caliph made no such suggestion to Charlemagne, but sent him extravagant presents: jewels, ivory chessmen, embroidered silken gowns, a water clock and a tame white elephant called Abu al-Abbas. Named after the first caliph of the Abbasid dynasty, the animal had once been the property of an Indian rajah. The man who successfully led it home from the Euphrates to the Mediterranean was a Jew named Isaac, sole survivor of a three-man mission to Baghdad. After a hazardous sea crossing to Italy, the elephant was led over the Alps and finally plodded into Charlemagne’s palace in Aix-la-Chapelle on 20 July 802. The emperor soon became devoted to Abu al-Abbas, who withstood the European climate for eight years, until Charlemagne rashly took him to the bleak Luneberg Heath in northern Germany, to intimidate some marauding Danes.2

These contacts between the caliph of Baghdad and the ‘philosopher-king’ of the Franks had proved to be only a brief flicker of light across the religious and cultural divide. Charlemagne had arranged, with Harun’s approval, for the founding of a Christian hostelry in Jerusalem, and this was the basis of a medieval legend that he had been the first crusader, leading a pilgrim army to the Holy Land. However, the Crusades were launched later – by Pope Urban II in 1095 – and the Arabs were then to be stunned by the uncouth ferocity of their religious foes.

Whereas Christian Europe was confined and cut off from Asia, the non-Christian Europeans – the Arabs settled in Spain and the Mediterranean islands – were free to wander across all the known world, even as far as China. It meant travelling first through Egypt and Arabia to reach some port such as Siraf, from where the ‘China ships’ set out on what was then the longest voyage known to mankind. In one of Buzurg’s stories there is a passing mention of a man originally from Cadiz who had been bold enough to stow away on a ship bound for China. This man had crossed the divide between two contrasting maritime traditions. The twisting, creaking vessel destined for China would have been totally unlike the heavy, broad-bottomed craft, held together with massive nails, which he would have remembered seeing in the harbours of Spain.

The use of coconut-fibre cording to sew the timbers of the Indian Ocean ships was often explained away by the myth of the ‘Magnetic Mountain’; that ships built with nails were doomed if they sailed near the mountain, since every scrap of metal in their hulls flew out towards it. In one of the Sinbad tales, a captain ‘hurls his turban on the deck and tears his beard’ when the Magnetic Mountain looms up in front of his ship, for he knows he is doomed: ‘The nails flew from the ship and shot off towards the mountain. The vessel fell to pieces and we were all flung into the raging sea. Most of us were drowned outright.’3