Полная версия:

The GI Walking Diet: Lose 10lbs and Look 10 Years Younger in 6 Weeks

Joanna Hall

THE GI

WALKING

DIET

LOSE 10LBS AND 10 YEARS IN 6 WEEKS

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Introduction: Active Ageing – One Foot in the Future

Part I: Dealing Positively with Ageing

1 Physical Changes

How Old Do You Feel?

Changing Your Attitudes and Habits

How the Body Ages

Ageing and Body Weight

2 Emotional Challenges

Emotional Stress

Emotional Eating

3 Making it Happen – Changing Habits and Attitudes

Get Active!

Small Steps for Big Change

What Is a Habit?

Have I Left it Too Late?

Part II: Opening the Window of Opportunity

4 How the GI Walking Diet Works

The Exercise Plan

The Eating Plan

5 Getting Ready for Action

Your Five-minute Body Road Test

Establishing Body Facts

Testing Your Fitness

6 The Six-week Exercise Plan

How Hard Should I Be Exercising?

Warming Up and Cooling Down

The Walking Plan

The Strength Plan

The Flexibility Plan

The Balance Plan (Optional)

Check Your Posture

7 The Six-week Eating Plan

How the Eating Plan Works

The Macronutrients You Need

The Micronutrients You Need

The Anutrients You Need

Drinks

The Menu Plans

8 Meal Ideas and Recipes

Breakfasts

Lunches

Carb Curfew Dinners

Carb Curfew Soups and Stews

Carb Curfew Desserts

Snacks

Glossary

About the Author

By the Same Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction: Active Ageing – One Foot in the Future

Ageing isn’t really ageing – it’s inactivity that’s the problem

As we progress through life, we may find it more challenging to be as active as we once were. The ageing process imposes changes upon our bodies that can gradually reduce our capabilities, but this can be compounded by lack of physical activity. There are many reasons for being inactive. Often, life seems to get in the way as we spend time focusing on careers, bringing up a family or caring for elderly relatives. We may be so busy that we feel guilty about taking time out for ourselves. Whatever the reasons, you may find your middle has got thicker and you’re not feeling quite the way you’d like to at this stage in your life.

Sedentary lifestyles contribute to a number of physical complaints that start to creep in as we get older. Suffering from – or a fear of suffering from – arthritis, diabetes, osteoporosis, creaky knees or a troublesome back can all be potential barriers to getting us moving. The sad truth is that by not taking an active role in your body’s ageing, you are accelerating the process of decay. Yet there is a viable alternative that can make you feel better, look better and lose that middle-age spread.

How Active are You?

Asking people to define their level of activity is often a sensitive issue. In my experience of working with clients, I have found that many of us tend to overestimate how active we are. This is not because we are lazy, though some of us by our own admission do prefer to curl up with a good book. To me, the confusion comes from the different ways we can define being active.

Ask anyone about their day and they usually reply that they are tired because they have been very busy and active. We naturally associate tiredness with a physically active day. When you probe a bit deeper, however, you often find that their day has not been physically active – it has been active in quite a different way. You can, in fact, be geographically or mentally active.

Here’s the scenario for a geographically active day. You wake up and think about the things that have to be done. You need to drop clothes off at the dry cleaners, pick up dog food for Fido, get to work, get across town for a lunch meeting, get back to the office to finish a report, grab something for dinner at the supermarket, get home, unload the car, cook dinner, get things ready for tomorrow. It gets to 8pm. You are tired. You have had a busy day and you’ve been all over town but you have not moved your body much – the car has moved, the train has moved but in reality your body has not really moved that much. You have been geographically active but not physically active.

Here’s the scenario for a mentally active day. You wake up in the morning, having been up half the night thinking about all the things you need to do. The monthly report needs to be completed before 10am, and the sales director wants figures by 11am. You’ve got a dinner party to plan for Saturday night, and you need to do the online shop by midday to get the home delivery service to deliver by 5pm on Friday. Your tax return is late so you need to get on with it. You also need to speak to the family about the arrangements for Christmas or that special occasion. It gets to 8pm. You are tired. You have had a busy day. Your brain has been all over the place – but you have not moved your body much. You have been mentally active but not physically active.

Our days will always be geographically active and mentally active but we have to encourage ourselves to be more physically active, and this is where this book comes in.

Time for Action

At this stage in your life, you may find you have more time for yourself than before. Your children may have left home. You may be retired or working part-time. This could be a real opportunity for you to make time to get active.

I have designed the GI Walking Diet to be realistic and achievable for everyone. What one person might find achievable could be difficult for someone else. That’s why you will find a variety of programmes that actively assist and guide you to improve your health and fitness and achieve sustainable weight loss. While the overall plan guides you to walk your way to fitness, weight loss and health improvements in just six weeks, your progress starts with small steps that are achievable for just about everyone.

In Chapter 1 we’ll look at the physical changes that occur as we get older. Chapter 2 tells you all about the emotional side of ageing. Chapter 3 explains how taking small steps can bring about big changes to your lifestyle. In Chapter 4 you’ll find out about the GI Walking Diet, why it’s achievable and the huge impact it can have on your health. In Chapter 5 we’ll address exactly where you are now and how you can get ready for your six-week plan. In Chapters 6 and 7, the plan is clearly laid out. All the exercises are described and illustrated so they are easy to follow, and the week-by-week guide gives you both a structure and a flexible approach to success, guiding you to achievable results, whatever your ability. Getting in shape and losing weight doesn’t mean missing out on great food, and in Chapter 8 you’ll find delicious recipes that easily fall in with the GI style of eating you can enjoy on your way better health.

Having good intentions about starting a diet and exercise plan is one thing – knowing where to start can be a minefield. My specially-designed ‘at a glance guides’ in Chapter 6 will help you get going. You can use them as starting points or as handy references as you progress with the programme.

Weight loss can be a significant motivator for us to change our habits, get a grip and make a difference. As we get older, however, it can seem more difficult to lose weight. We may also become more accepting of our expanding waistlines. Many people mistakenly believe that the only way to improve their health is to lose large amounts of weight and spend lots of time exercising, which just seems like too much effort. For many, a rotund, cuddly figure can become an acceptable part of later life.

But stop right there! You can make a significant difference to your health without too much hard work. You don’t have to lose large amounts of weight to experience real health benefits. In fact, a weight loss of just 5–10 per cent provides major health benefits. So, if you weigh 16 stone (100kg), a drop of between 8lb (3kg) to 1 stone 2lb (7kg) can make a major difference. Accepting this fact makes the whole process much more realistic and achievable.

So the time has come to take action. No more excuses. Stop kidding yourself – or your middle-age spread and muscle stiffness are here to stay. Start taking small steps to create big changes to your health, your weight, your fitness, your energy and your self-esteem. If you’re ready, I’ll show you how.

I Dealing Positively with Ageing

Fitness for a young person is an option – for an older person it’s imperative

1 Physical Changes

“I don’t feel old. I don’t feel anything till noon.

Then it’s time for my nap.” Bob Hope

How Old Do You Feel?

So you woke up this morning, got out of bed and looked in the mirror – what did you think of the person staring back at you? You may be a parent, a grandparent, a lover, a wife, a husband, a son, a daughter. But as you reflect on yourself and your current stage in life, how do you actually feel about yourself and how do you see your body?

Do you think of yourself as:

In my research for this book, I interviewed over a thousand men and women aged over 50. I asked them about their eating and activity habits, for their views on their bodies and their attitudes to this phase of their lives. Their thoughts, views, needs and wants – coupled with the exciting new advances being made in research – have directly shaped this book.

So what did my research tell me?

Changing Your Attitudes and Habits

You may feel daunted by the physical changes you are experiencing as you grow older. However, the exciting thing about this phase is that you now have the ability – more than at any other time in your life – to make a significant impact on your health. You also have more to gain from your efforts than at any other time.

Active ageing is as much about attitude as it is about action. Your children may have flown the nest; you may have retired; you may have more time on your hands – and this is the time for you. It’s an age of choice without limitations, a time of joy with few constraints. While some of us may still have some demands on our time, this does not detract from the fact that this stage in your life represents the best window of opportunity for your physical body.

And you know what? The only things that may be stopping you from taking action are your attitude and deep-rooted habits. Attitudes and habits can be difficult to change – after all, you may have been nurturing them for decades.

I’ve designed all the plans in this book so you can grab and make the most of this window of opportunity. They not only deliver results but also help you nurture new, healthier habits and attitudes without feeling you have to give up the life you enjoy. By making small changes on a regular, consistent basis, you can lose weight, feel fitter, enjoy more energy and even sleep better. These small steps together mean big changes for you and your body.

So don’t you dare think you’ve left it too late. It’s never too late. The time has come to open the window of opportunity, stop being complacent about this phase of your life, take a deep breath and go for it.

One Step at a Time

When you first look at the plan you may feel a little daunted about what you have to do. The plan has been designed to be simple and easy to follow. You’ll see that you get to choose whether to start the walking plan at an ‘entry’ or ‘advanced’ level, depending on your current fitness level (see Chapter 4).

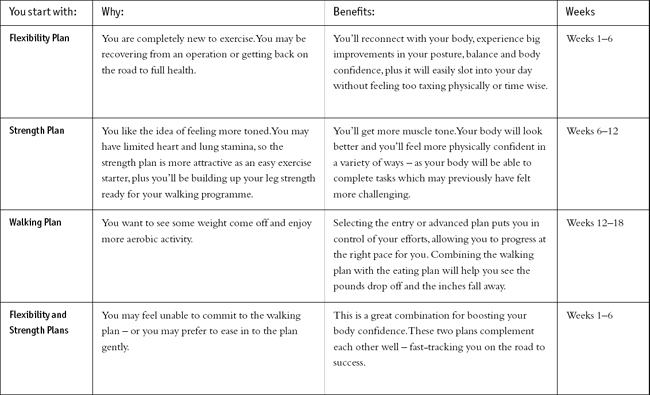

I’d be the first to acknowledge, however, that life can be busy and throw us different challenges. Family commitments, work and health issues can all make it seem difficult to find time to exercise. While I wouldn’t encourage you to use these busy times as excuses, I’d far rather you did something than wait for the ‘perfect’ time to start. In my experience, the perfect time rarely comes, and since this stage of your life is your greatest window of opportunity, this may be the perfect time to approach your plan in a phased way. For example, you may choose to follow the flexibility plan for the first six weeks, then the strength programme for weeks six to twelve, and finally the walking plan for weeks twelve to eighteen. A phased approach such as this will get you on the road to success. You’ll feel healthier and more in control, although your weight loss may be a little slower than if you were following the complete plan.

Timetable for a Phased Approach to the GI Walking Diet

How the Body Ages

Nobody wants their body to age, but the great news is that you can slow down the rate of ageing. In fact, ageing can a positive experience, not the negative one many of us feel and dread.

In physical terms, the ageing process results in a gradual loss of coordination, flexibility, strength, power and endurance. These physiological changes can have a significant impact on our emotions, our ability to lead independent lives and our energy and self-esteem.

Whether you like it or not, your body will go through a number of changes as it ages. How these changes affect you is partly dependent on your genes, diet, and how physically active you have been through your life. Think about how your parents or siblings have aged and you’ll have a good indication of how your body is affected by your genes. The geneticist Claude Bouchard believes that genes determine 60 to 80 per cent of the body’s rate of physical change; other factors, such as diet and the amount and type of physical activity we take, can change our bodies by 20 to 40 per cent.

Fortunately, evidence suggests that your physical activity levels after the age of 35 can have a more significant effect on how you age than the amount of exercise taken in earlier years. Although you may not be able to reverse declines in physical function, they can be slowed down. Understanding what is happening to your body can help you appreciate how your diet and activity levels can positively impact upon your weight, energy, posture and, most importantly, how you look and feel about yourself.

A fit man at 70 is the same as an unfit man at 40.

Much of the deterioration attributed to ageing is now linked to physical inactivity. Our goal is to push back frailty to a very small part of life experience. Or, as the philosopher Ashley Montagne has urged, ‘To die young as late in life as possible.’

You can do this without spending masses of time exercising, waving goodbye to your existing lifestyle or surviving on a diet of bizarre foods. And you can do this in just six weeks.

Ageing and Physical Ability

Strength, power, endurance and flexibility are terms we often hear, but understanding exactly what they mean will help you appreciate your own body’s needs, allowing you to tailor the six-week plan to your needs.

Strength and Power

Muscular strength refers to the maximum force that can be exerted by a muscle group. You may be more familiar with strength referring to the maximum weight or load that can be lifted once. Power refers to the greatest amount of force that can be exerted, and requires both strength and speed of movement. This may all sound rather technical, but in real terms the impact of these capacities on your body can be far-reaching. Muscle strength declines significantly with advancing age, which results in a decreased ability to perform many daily tasks. Activities such as lifting heavy shopping bags can become difficult. Your grandchild may need to be handed to you rather than you being able to lift them directly from the floor. Even getting out of a low chair can pose a problem, perhaps requiring a few momentum-gathering rocks backwards and forwards to get you up. Later in life, both strength and power are important for balance and reducing the risk of falling.

Endurance

Endurance, often referred to as stamina, is a muscle’s ability to keep going. All muscles need endurance – the muscles of your legs need it to keep walking, for example – but one of the most important muscles is the heart. The endurance of your heart is vital to your wellbeing, and it’s often referred to as your ‘huff and puff’. Having poor endurance means that it can be hard work running after a bus, train or walking briskly up a hill. Climbing a flight of stairs can leave you feeling uncomfortable and breathless. If you have young grandchildren, you’ll know how much energy and endurance they have and how you need to be able to keep up with them!

Flexibility and Mobility

Flexibility refers to the range of motion at a particular joint, while mobility refers to the ability to take your joints through this range. Flexibility and mobility are determined by the elasticity of the connective tissue, as well as the specific length of individual ligaments and tendons. As we age, the connective tissue becomes less elastic. The special lubricating synovial fluid – found inside certain joints such as the hip, knee and shoulder – becomes less mobile and runny. This makes joints feel stiff and perhaps a bit ‘clicky’, limiting the range of motion we may be able to take them through. This can make it difficult to unzip a back-fastening piece of clothing, to reach up for something on a top shelf or to bend down to pick something up. Maybe even getting your leg up and over the bath can be a bit of a challenge, requiring you to hold on to something for support. Or perhaps you find when you need to turn to see something you have to turn your whole body around, instead of just being able to rotate at your waist.

The bottom line is that maintaining your level of physical capacity in terms of strength, endurance and flexibility is very important for continued independence. Power, strength and flexibility are all closely related, and improving one of these will have a knock-on effect on the others. The GI Walking Diet enables you to improve all these abilities in a simple, effective and easy-to-follow way.