Полная версия:

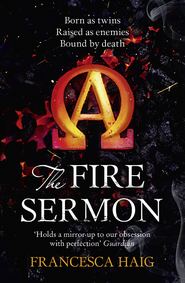

The Fire Sermon

Copyright

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2015

Copyright © De Tores Ltd 2015

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover illustration and title typography created by Alexandra Allden

Other cover images © Shutterstock.com (additional figure and tree features)

Francesca Haig asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007563050

Ebook Edition © February 2015 ISBN: 9780007563074

Version: 2016-03-10

Praise for Francesca Haig

‘This terrific set-up spools out into a high-tension tale of mistrust and dependency, injustice and optimism, told with poetic intensity’

Daily Mail

‘Haig’s post-apocalyptic world is colourfully fleshed out, and the conclusion asks us to consider who, really, is the Other’

Washington Post

‘It holds a mirror up to our obsession with perfection’

Guardian

‘Words like “masterpiece” and “instant classic” are cliché, but in the case of Francesca Haig’s astounding The Fire Sermon, they’re the only words to use. It’s a breath-taking, passionate, absolutely sensational work of imagination, perfectly structured, beautifully written, populated with fabulous characters and packed with intrigue, violence, compassion and underlined by a very important human message that is always present without ever becoming homily. The Fire Sermon is completely without equal – it leaves Hunger Games, Divergent, Twilight blah blah-yawn twitching in the dust’

Starburst Magazine

‘A hell of a ride. I would recommend it to anyone I can, regardless of age’

JAMES OSWALD

‘This book is a thought-provoking whirlwind of a story, with a fab lead character, grisly politics and brave adventure. I loved it!’

JESSIE BURTON

Dedication

This book is dedicated, with love and admiration, to my brother, Peter, and my sister, Clara. Knowing how much they mean to me, it should come as no surprise that my first novel is about siblings.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Acknowledgements

Read an Extract of The Map of Bones

About the Author

About the Publisher

CHAPTER 1

I’d always thought they would come for me at night, but it was the hottest part of the day when the six men rode onto the plain. It was harvest time; the whole settlement had been up early, and would be working late. Decent harvests were never guaranteed on the blighted land permitted to Omegas. Last season, heavy rains had released deeply buried blast-ash in the earth. The root vegetables had come up tiny, or not at all. A whole field of potatoes grew downwards - we found them, blind-eyed and shrunken, five feet under the mucky surface. A boy drowned digging for them. The pit was only a few yards deep but the clay wall gave way and he never came up. I’d thought of moving on, but all the valleys were rain-clogged, and no settlement welcomed strangers in a hungry season.

So I’d stayed through the bleak year. The others swapped stories about the drought, when the crops had failed three years in a row. I’d only been a child, then, but even I remembered seeing the carcasses of starved cattle, sailing the dust-fields on rafts of their own bones. But that was more than a decade ago. This won’t be as bad as the drought years, we said to one another, as if repetition would make it true. The next spring, we watched the stalks in the wheat fields carefully. The early crops came up strong, and the long, engorged carrots we dug that year were the source of much giggling amongst the younger teenagers. From my own small plot I harvested a fat sack of garlic which I carried to market in my arms like a baby. All spring I watched the wheat in the shared fields growing sturdy and tall. The lavender behind my cottage was giddy with bees and, inside, my shelves were loaded with food.

It was mid-harvest when they came. I felt it first. Had been feeling it, if I were honest with myself, for months. But now I sensed it clearly, a sudden alertness that I could never explain to anybody who wasn’t a seer. It was a feeling of something shifting: like a cloud moving across the sun, or the wind changing direction. I straightened, scythe in hand, and looked south. By the time the shouts came, from the far end of the settlement, I was already running. As the cry went up and the six mounted men galloped into sight, the others ran too – it wasn’t uncommon for Alphas to raid Omega settlements, stealing anything of value. But I knew what they were after. I knew, too, that there was little point in running. That I was six months too late to heed my mother’s warning. Even as I ducked the fence and sprinted toward the boulder-strewn edge of the settlement, I knew they would get me.

They barely slowed to grab me. One simply scooped me up as I ran, snatching the earth from under my feet. He knocked the scythe from my hand with a blow to my wrist and threw me face-down across the front of the saddle. When I kicked out, it only seemed to spur the horse to greater speed. The jarring, as I bounced on my ribs and guts, was more painful than the blow had been. A strong hand was on my back, and I could feel the man’s body over mine as he leaned forward, pressing the horse onwards. I opened my eyes, but shut them again swiftly when I was greeted by the upside-down view of the hoof-whipped ground bolting by.

Just when we seemed to be slowing and I dared to open my eyes again, I felt the insistent tip of a blade at my back.

‘We’re under orders not to kill you,’ he said. ‘Not even to knock you out, your twin said. But anything short of that, we won’t hesitate, if you give us any trouble. I’ll start by slicing a finger off, and you’d better believe I wouldn’t even stop riding to do it. Understand, Cassandra?’

I tried to say yes, managed a breathless grunt.

We rode on. From the endless jolting and the hanging upside down, I was sick twice – the second time on his leather boot, I noted with some satisfaction. Cursing, he stopped his mount and hauled me upright, looping a rope around my body so that my arms were bound at my sides. Sitting in front of him, the pressure in my head was eased as the blood flowed back down to my body. The rope cut into my arms but at least it held me steady, grasped firmly by the man at my back. We travelled that way for the rest of the day. At nightfall, when the dark was slipping over the horizon like a noose, we stopped briefly and dismounted to eat. Another of the men offered me bread but I could manage only a few sips from the water flask, the water warm and musty. Then I was again hoisted up, in front of a different man now, his black beard prickling the back of my neck. He pulled a sack over my head, but in the darkness it made little difference.

I sensed the city in the distance, long before the clang of hoofs beneath us indicated that we’d reached paved roads. Through the sacking covering my face, glints of light began to show. I could feel the presence of people all about me – more even than at Haven on market day. Thousands of them, I guessed. The road steepened as we rode on, slowly now, the hoofs noisy on cobbles. Then we halted, and I was passed, almost tossed, down to another man, who dragged me, stumbling, for several minutes, pausing often while doors were unlocked. Each time we moved on, I heard the doors being locked again behind us. Each scrape of a bolt sliding back was like another blow.

Finally, I was pushed down onto a soft surface. I heard a rasp of metal behind me, a knife sliding from a sheath. Before I had time to cry out, the rope around my body fell away, slit. Hands fumbled at my neck, and the sack was ripped from my head, the rough hessian grazing my nose. I was on a low bed, in a small room. A cell. There was no window. The man who’d untied me was already locking the metal door behind him.

Slumped on the bed, the taste of mud and vomit in my mouth, I finally allowed myself to cry. Partly for myself, and partly for my twin; for what he’d become.

CHAPTER 2

The next morning, as usual, I woke from dreams of fire.

As the months passed, the moments after such dreams were the only times I was grateful to wake to the confines of the cell. The room’s greyness, the familiarity of its implacable walls, were the opposite of the vast and savage excess of the blast I dreamed of nightly.

There were no written tales or pictures of the blast. What was the point of writing it, or drawing it, when it was etched on every surface? Even now, more than four hundred years after it had destroyed everything, it was still visible in every tumbled cliff, scorched plain, and ash-clogged river. Every face. It had become the only story the earth could tell, so who else would record it? A history written in ashes, in bones. Before the blast, they say there’d been sermons about fire, about the end of the world. The fire itself gave the last sermon; after that there were no more.

Most who survived were deafened and blinded. Many others found themselves alone – if they told their stories, it was only to the wind. And even if they had companions, no survivor could ever properly describe the moment it happened: the new colour of the sky, the roar of sound that ended everything. Struggling to describe it, the survivors would have found themselves, like me, stranded in that space where words ran out and sound began.

The blast shattered time. In an instant, it cleaved time irrevocably into Before and After. Now, hundreds of years later, in the After, no survivors remained, no testimonies. Only seers like me could glimpse it, momentarily, in the instant before waking, or when it ambushed us in the half-second of a blink: the flash, the horizon burning up like paper.

The only tales of the blast were sung by the bards. When I was a child, the bard who passed through the village each autumn sang of other nations, across the sea, sending the flame down from the sky, and of the radiation and the Long Winter that had followed. I must have been eight or nine when, at Haven market, Zach and I heard an older bard with frost-grey hair singing the same tune but with different words. The chorus about the Long Winter was the same, but she made no mention of other nations. Each verse she sang just described the fire, and how it had consumed everything.

When I’d pulled our father’s hand and asked him, he’d shrugged. There were lots of versions of the song, he said. What difference did it make? If there’d once been other lands, across the sea, there were no longer, as far as any sailor had lived to tell. The occasional rumours of Elsewhere, countries over the sea, were only rumours – no more to be believed than the rumours about an island where Omegas lived free of Alpha oppression. To be overheard speculating about such things was to invite public flogging, or to end up in the stocks, like the Omega we’d once seen outside Haven, pinned under the scathing sun until his tongue was a scaled blue lizard protruding from his mouth, while two bored Council soldiers kept watch, kicking him from time to time to ensure he was still alive.

Don’t ask questions, our father said; not about the Before, not about Elsewhere, not about the island. People in the Before asked too many questions, probed too far, and look what that got them. This is the world now, or all we’ll ever know of it: bounded by the sea to the north, west, and south; the deadlands to the east. And it made no difference where the blast came from. All that mattered was that it came. It was all so long ago, as unknowable as the Before that it had destroyed, and from which only rumours and ruins remained.

*

In my first months in the cell, I was granted the occasional gift of sky. Every few weeks, in the company of other imprisoned Omegas, I was escorted on to the ramparts for some exercise and a few moments of fresh air. We were taken in groups of three, with at least as many guards. They watched us carefully, keeping us not only apart but also well away from the crenellations that overlooked the city below. The first outing, I’d learned not to try to approach the other prisoners, let alone to speak. As the guards escorted us up from the cells, one of them had grumbled about the slow pace of the pale-haired prisoner, hopping on one leg. ‘I’d be quicker if you hadn’t taken away my cane,’ she’d pointed out. They didn’t respond, and she’d rolled her eyes at me. It wasn’t even a smile, but it was the first hint of warmth I’d seen since entering the Keeping Rooms. When we reached the ramparts, I’d tried to sidle close enough to her to attempt a whisper. I was still ten feet from her when the guards tackled me against the wall so hard that my shoulder-blades were bruised against the stone. As they hustled me back down to the cell one of them spat at me. ‘Don’t talk to the others,’ he said. ‘Don’t even look at them, do you hear?’ With my arms held behind my back, I couldn’t wipe his spittle from my cheek. Its warmth was a foul intimacy. I never saw the woman again.

A month or more later was my third outing to the ramparts, and the last for any of us. I was standing by the door, letting my eyes accustom to the glint of sun on polished stone. Two guards stood to my right, chatting quietly. Twenty feet to my left, another guard leaned against the wall, watching a male Omega. He’d been in the Keeping Rooms longer than me, I guessed. His skin, which must once have been dark, was now a dirty grey. More telling were the twitchy motions of his hands, and the way he kept moving his lips, as if they didn’t fit over his gums. The whole time we’d been up there, he had walked backwards and forth on the same small patch of stones, dragging his twisted right leg. Despite the interdiction on speaking to one another, I could periodically hear his muttered counting: Two hundred and forty-seven. Two hundred and forty-eight.

Everyone knew that many seers went mad – that over years the visions burned our minds away. The visions were flame, and we were the wick. This man wasn’t a seer, but it didn’t surprise me that anyone held for long enough in the Keeping Rooms would go mad. What chance, then, for me, contending with the visions at the same time as the unrelenting walls of my cell? In a year or two, I thought, that might be me, counting out my footsteps as if the neatness of numbers could impose some order on a broken mind.

Between me and the pacing man was another prisoner, perhaps a few years older than me, a one-armed woman with dark hair and a cheerful face. It was the second time we’d been taken to the ramparts together. I walked as close to the edge of the ramparts as the guards would allow, and stared beyond the sandstone crenellations as I tried to contrive some way that I might speak or signal to her. I couldn’t get close enough to the edge to get a proper look at the city that unfolded beneath the mountainside fort. The horizon was curtailed by the ramparts, beyond which I could see only the hills, painted grey with distance.

I realised the counting had stopped. By the time I’d turned around to see what had changed, the older Omega had already rushed at the woman and gripped her neck between his hands. With only one arm she couldn’t fight hard enough or cry out quickly enough. The guards reached them while I was still yards away, and in seconds they’d pulled him off her, but it was too late.

I’d closed my eyes to block the sight of her body, face down on the flagstones, head turned sideways at an impossible angle. But for a seer there’s no refuge behind closed eyelids. In my shuddering mind I saw what else happened at precisely the moment that she died: a hundred feet above us, inside the fort, a glass of wine dropped, sharding red over a marble floor. A man in a velvet jacket fell backwards, scrambled for a second to his knees, and died, his hands to his neck.

After that, there were no more trips to the ramparts. Sometimes I thought I could hear the mad Omega shouting and thrashing the walls, but it was only a dull thud, a throb in the night. I never knew whether I was really hearing it, or just sensing it.

Inside my cell, it was almost never dark. A glass ball suspended in the ceiling gave off a pale light. It was lit constantly, and emitted off a slight buzz, so low that I sometimes wondered whether it was just a ringing in my own ears. For the first few days I watched it nervously, waiting for it to burn out and leave me in total darkness. But this was no candle, not even an oil lamp. The light it gave off was different: cooler, and unwavering. Its sterile light only faltered every few weeks, when it would flicker for several seconds and disappear, leaving me in a formless black world. But it never lasted more than one or two minutes. Each time the light would return, blinking a couple of times, like somebody waking from sleep, before resuming its vigil. I came to welcome these intermittent breakdowns. They were the only interruptions from the light’s ceaseless glare.

This must be the Electric, I supposed. I’d heard the stories: it was like a kind of magic, the key to most of the technology from the Before. Whatever it had been, though, it was supposed to be gone now. Any machines not already destroyed in the blast had been done away with in the purges that followed, when the survivors had destroyed all traces of the technology that had brought the world to ash. All remnants of the Before were taboo, but none more than the machines. And while the penalties for breaking the taboo were brutal, the law was mainly policed by fear alone. The danger was inscribed on the surface of our scorched world, and on the twisted bodies of the Omegas. We needed no reminders.

But here was a machine, a piece of the Electric, hanging from the ceiling of my cell. Not anything terrifying or powerful, like the things people whispered about. Not a weapon, or a bomb, or even a carriage that could move without a horse. Just this glass bulb, the size of my fist, blaring light at the top of my cell. I couldn’t stop staring at it, the knot of extreme brightness at its core, sharply white, as though a spark from the blast itself were captured there. I stared at it for so long that when I closed my eyes the bright shape of it was etched on my eyelids’ darkness. I was fascinated, and appalled, wincing beneath the light in those first days as though it might explode.

When I watched the light, it wasn’t only the taboo that scared me – it was what this act of witness meant for me. If word got out that the Council was breaking the taboo, there’d be another purge. The terror of the blast, and the machines that had wrought it, was still too real, too visceral, for people to tolerate. I knew the light was a life sentence: now I’d seen it, I’d never be allowed out.

More than anything else, I missed the sky. A narrow vent, just below the ceiling, let in fresh air from somewhere, but never even a glimpse of sunlight. I calculated time’s passage by the arrival of food trays twice a day through the slot in the base of the door. As the months since that last visit to the ramparts receded, I found I could recall the sky in the abstract, but couldn’t properly picture it. I thought of the stories of the Long Winter, after the blast, when the air had been so thick with ash that nobody saw the sky for years and years. They say there were children born in that time who never saw the sky at all. I wondered whether they’d believed in it; whether imagining the sky had become an act of faith for them, as it now was for me.

Counting days was the only way I could cling to any sense of time, but as the tally grew it became its own torture. I wasn’t counting down towards any prospect of release: the numbers only climbed, and with them the sense of suspension, of floating in an indefinite world of darkness and isolation. After the visits to the ramparts were stopped, the only regular milestone was The Confessor coming each fortnight to interrogate me about my visions. She told me that the other Omegas saw no one. Thinking of The Confessor, I didn’t know if I should envy or pity them.

*

They say the twins started to appear in the second and third generations of the After. In the Long Winter there were no twins – barely any births at all, and fewer who survived. They were the years of melted bodies and failed, unrecognisable infants. So few lived, and fewer still could breed, so that it seemed unlikely humans would carry on at all.

At first, in the struggle to repopulate, the onslaught of twins must have been greeted with joy. So many babies, and so many of them normal. There was always one boy and one girl, with one from each pair perfect. Not just well formed, but strong, robust. But soon the fatal symmetry became evident; the price to be paid for each perfect baby was its twin. They came in many different forms: limbs missing, or atrophied, or occasionally multiplied. Absent eyes, extra eyes, or eyes sealed shut. These were the Omegas, the shadow counterparts to the Alphas. The Alphas called them mutants, said they were the poison that Alphas cast out, even in the womb. The stain of the blast that, while it couldn’t be removed, had at least been displaced onto the lesser twin. The Omegas carried the burden of the mutations, leaving the Alphas unencumbered.