скачать книгу бесплатно

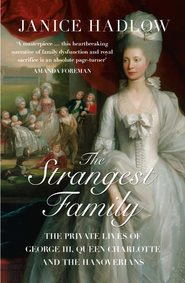

The Strangest Family: The Private Lives of George III, Queen Charlotte and the Hanoverians

Janice Hadlow

An intensely moving account of George III’s doomed attempt to create a happy, harmonious family, written with astonishing emotional force by a stunning new history writer.George III came to the throne in 1760 as a man with a mission. He wanted to be a new kind of king, one whose power was rooted in the affection and approval of his people. And he was determined to revolutionise his private life too – to show that a better man would, inevitably, make a better ruler. Above all he was determined to break with the extraordinarily dysfunctional home lives of his Hanoverian forbears. For his family, things would be different.And for a long time it seemed as if, against all the odds, his great family experiment was succeeding. His wife, Queen Charlotte, shared his sense of moral purpose, and together they did everything they could to raise their tribe of 13 young sons and daughters in a climate of loving attention. But as the children grew older, and their wishes and desires developed away from those of their father, it became harder to maintain the illusion of domestic harmony. The king's episodes of madness, in which he frequently expressed his repulsion for the queen, undermined the bedrock of their marriage; his disapproving distance from the bored and purposeless princes alienated them; and his determination to keep the princesses at home, protected from the potential horrors of the continental marriage market, left them lonely, bitter and resentful at their loveless, single state.At one level, ‘The Strangest Family’ is the story of how the best intentions can produce unhappy consequences. But the lives of the women in George's life – and of the princesses in particular – were shaped by a kind of undaunted emotional resilience that most modern women will recognise. However flawed George's great family experiment may have been, in the value the princesses placed on the ideals of domestic happiness, they were truly their father's daughters.

Copyright

(#u8a55c912-75b5-59cf-82fb-962e986f9e77)

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com (http://www.williamcollinsbooks.com)

First published in Great Britain by William Collins 2014

Copyright © Janice Hadlow 2014

Janice Hadlow asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Cover image: Queen Charlotte, 1779 (oil on canvas) by West, Benjamin (1738–1820)/Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2015/Bridgeman Images

Source ISBN: 9780007165193

Ebook Edition © August 2014 ISBN: 9780008102203

Version: 2015-06-29

Frontispiece

(#u8a55c912-75b5-59cf-82fb-962e986f9e77)

George III, Queen Charlotte and six princesses (watercolour, attributed to William Rought)

Dedication

(#u8a55c912-75b5-59cf-82fb-962e986f9e77)

FOR MARTIN, ALEXANDER AND LOUIS,

AND FOR MY PARENTS, WHO DID NOT LIVE TO READ IT

Contents

Cover (#u881d3a83-4271-552b-9641-c7cf2809e562)

Title Page (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#ulink_4d8a6f72-4b6e-56d6-b0b7-debaf1c4d586)

Frontispiece (#ulink_ed44981a-cf65-55d9-bc33-7be6f5dc6a3b)

Dedication (#ulink_22913441-25ac-59fd-a387-331536af583a)

Author’s Note (#ulink_4562aff5-0c56-5450-bc6f-0e04fd9ed7bc)

Epigraphs (#ulink_2e10dfad-a35c-56cc-ab57-e205f9ca5f6a)

Family Tree (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#ulink_9f9068bc-0ea2-55ae-97d4-4daecb4cd6d5)

1 The Strangest Family (#ulink_5c89d6ab-bdee-5b47-9f48-9e01a620e81b)

2 A Passionate Partnership (#ulink_912ff760-b0a4-5782-b8cb-3161226bbd7a)

3 Son and Heir (#ulink_a46d8702-92fe-54e1-ad36-5254bf538964)

4 The Right Wife (#ulink_5282a795-1826-5d3c-807c-f292e6f1e0c6)

5 A Modern Marriage (#ulink_d84a0e06-d9a2-51d2-b9ef-0b329f9582e2)

6 Fruitful (#litres_trial_promo)

7 Private Lives (#litres_trial_promo)

8 A Sentimental Education (#litres_trial_promo)

9 Numberless Trials (#litres_trial_promo)

10 Great Expectations (#litres_trial_promo)

11 An Intellectual Malady (#litres_trial_promo)

12 Three Weddings (#litres_trial_promo)

13 The Wrong Lovers (#litres_trial_promo)

14 Established (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Picture Section (#litres_trial_promo)

Illustration Credits (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note

(#u8a55c912-75b5-59cf-82fb-962e986f9e77)

WHEN QUEEN CHARLOTTE WAS ASKED by the artist, botanist and diarist Mrs Delany why she had appointed the writer Fanny Burney to the post of assistant dresser in her household, she answered with characteristic clarity: ‘I was led to think of Miss Burney first by her books, then by seeing her, then by hearing how much she was loved by her friends, but chiefly by her friendship for you.’ If questioned about why I wrote this book, I am not sure I could answer with such confident precision. In one sense, it simply crept up on me, emerging from a long love affair with the period and the people who lived in it.

I have always been fascinated by history. I studied it at university, where I was taught by some exceptional and inspiring teachers. As a television producer, I have made many history programmes, covering all aspects of the past – from the ancient world to times within living memory. I have worked with some of the most eminent British historians, witnessing at first-hand their knowledge and passion for a huge variety of subject areas. But it was always the eighteenth century that had first place in my heart. I had immersed myself in the politics of the period at college, but its appeal went far beyond what my reading delivered for me. Like so many others, I was drawn to it partly by the wonderful things made in it: the incomparable architecture that created austerely elegant palaces for the great, and airy, comfortable homes for the ‘middling sort’. I coveted the objects that went into these houses, from the sturdily beautiful furniture to the delicate blue-and-white coffee cups intended to sit proudly on all those much-polished tea tables. I admired the art of the period too, especially the portraiture, whether it was the clear-eyed intensity of Allan Ramsay, the bravura gestures of Joshua Reynolds, or the tender luminosity of Thomas Gainsborough. Those eighteenth-century men and women rich enough to afford it never tired of having themselves painted. If I had been one of them, I would have chosen Thomas Lawrence for my portrait. Who wouldn’t want to see themselves through Lawrence’s humane yet flattering eye, which infused even the most unpromising sitter with a sense of spirit and passion? I would have worn a red velvet dress, as both princesses Caroline and Sophia did when they sat for Lawrence, and hoped for a similarly impressive result: both women gaze directly out from their pictures, proud, commanding and smoulderingly bold. The portraits do not quite capture their true characters, at least as revealed in their letters; but what an image to look upon when your spirits needed a boost.

But much as I responded to the things the period produced, my real desire was to understand the people who lived in it. It was the men and women of what is often called the long eighteenth century – which runs from the accession of George I in 1714 to the death of George IV in 1830 – who really captivated me. Caught between the religious intensity of the seventeenth century and the earnest high-mindedness of the Victorians, this was a society in which I felt very much at home. I enjoyed its bustle and energy, and liked being in the company of its garrulous, argumentative and emotional inhabitants. The contradictions of their world intrigued me. On the one hand, they loved order, politeness, restraint. On the other, they were loud, forthright and often violent. The sedate drawing rooms of the rich looked out onto streets where passions could and did run very high. The poor, in both town and country, had a tough time of it, although they too seem to have shared something of the assertive confidence of the wealthy. For most of the middling sort, however, and especially for the rich, there was good reason to be bullish. This was a period in which there was money to be made, and a new kind of life to be lived. It is the experiences of these people – those who built the houses, big and small, laid out the gardens, commissioned the pictures, bought the furniture – that I have come to know best.

I knew them first by their books, and above all, through the work of Jane Austen. My earliest encounters with the authentic voice of the time came through her novels; the first eighteenth-century people I felt I really knew were the Bennetts of Longbourn, the Elliots of Kellynch Hall, Admiral and Mrs Croft, Mr Elton and his dreadful wife.

From fiction, it was a short jump to the world of real people. I think I began with James Boswell’s London Journal. That was my introduction to the vast and compelling world of eighteenth-century diaries and correspondence in which I have been happily immersed ever since. There are two reasons why I love nothing better than a collection of letters or a lengthy journal. Firstly, I’m gripped by the unfolding human story they capture, the narrative of real life as it is actually lived, the biggest events pressed hard up against the small details of the everyday round, matters of love and marriage, birth and death interspersed with accounts of dinner parties and shopping trips, the ups and downs of relationships, the likes and dislikes, triumphs and failures that are the stuff of all human experience. I always want to know what happened next, how things turned out. Did the marriage for which everyone had planned and schemed take place? Was it a success? Did the baby that seemed so sickly survive? Did the business venture prosper? Was a husband ever found for the awkward youngest sister, or a profession for the lacklustre youngest son?

Secondly, I so enjoy the way the letter- and diary-writers tell their stories. The eighteenth-century voice, in its most formal mode, can be stately and remote; but in more relaxed correspondence, the prevailing tone is quite different. Letters between family and friends have an immediacy and a directness that rarely fail to engage the reader. Educated eighteenth-century writers were extremely candid: there were few subjects that they considered off limits. They were intensely interested in themselves and their own concerns, thinking nothing of filling page after page with detailed analyses of their health, their thoughts, and the nature of their relationships, marital, professional or political. They were tremendous gossips. Some of them were also very funny, caustic, satiric, masters (and mistresses) of an ironic tone that feels very modern in its knowingness and is still able to raise a smile after so many years.

It is very easy, reading their letters, to feel that the people who wrote them are just like us. For me, that is part of the appeal of the period, and it is, to some extent, true. But in other ways, the reality of their lives is almost impossible for contemporary readers to appreciate. In the midst of a world that seems so sophisticated and so recognisable, eighteenth-century people encountered on a daily basis experiences which would horrify a modern sensibility. Outside the well-managed homes of the better-off, extremes of poverty and the brutal and degrading treatment of the powerless and vulnerable were everywhere to be found. Even the richest families lived with the constant spectre of sickness, pain and death and could not protect themselves against the disease that decimated a nursery, the accident that felled a promising young man or the complications that killed a mother in childbirth. There is a drumbeat of darkness in all the correspondence of this period that makes a modern reader pause to give thanks for penicillin and anaesthesia.

Many of the letter-writers who so assiduously chronicled the ebb and flow of family life were women. Then, as is perhaps still the case now, it was women who worked hardest to cement the social relationships that held scattered families and friends together. One of the ways they did this was by writing to everyone in their social circle, passing on news, advice and scandal, describing their feelings and speculating on the motives and emotions of those around them. This sprawling world of the family, especially the lives of women and children, is the territory I have always found most compelling. I am fascinated by the inner life of this intimate place and am endlessly curious about how it worked. I always want to find out who was happy and who was not, how duty was balanced with self-interest, and how power worked across the generations.

It was via these paths that I eventually came to fix upon the grandest family of them all as a suitable subject for a book. I had always been interested in George III, that much-misunderstood man, in whom apparently contradictory characteristics were so often combined: good-natured but obstinate, kind but severe, humane but unforgiving, stolid but with the occasional ability to deliver an unexpectedly sharp and penetrating insight. At first, however, it was the story of his wife and daughters that most attracted me. Queen Charlotte’s reputation was, both in her own time and afterwards, equivocal at best. In her lifetime, she endured a very bad press, excoriated by her critics as a plain, bad-tempered harridan, miserly and avaricious, interested principally in the preservation of rigid court etiquette and the taking of copious amounts of snuff. The real story, as her letters and the diaries and correspondence of those around her reveal, was rather different. Charlotte was never easy to love or, in later life, to live with, but she had a great deal to bear. She was a very clever woman in an age that found clever woman unsettling. Her intellectual appetite was unequalled by any of her successors, but could never be expressed in a way that threatened established expectations about how queens were supposed to behave. She spent nearly twenty years of her life in a state of almost constant pregnancy. In public she embraced this as the destiny of a royal wife; but, as her private correspondence makes clear, she resented the decades spent in child-bearing. Before it was crushed by the horror of the king’s illness, from which she never really recovered, and the pressures of her public role, which she sometimes found almost impossible to endure, her personality was much more attractive, sprightly, humorous and playful.

The lives of her six daughters seemed to contemporaries to contain little of interest except for the occasional whiff of scandal. They lingered unmarried for so long that they were described even by their own niece as ‘a parcel of old maids’. Their narrative is perhaps more familiar now – they were the subject of a group biography by Flora Fraser in 2004 – and it is clear that beneath the apparently bland uneventfulness of their existence, the princesses too were subject to strong emotions which were often expressed in circumstances of great personal drama. Their lives were dominated by their struggles to balance what they saw as their duty to their parents with some degree of self-determination and freedom to make their own choices. Where did the obligations they owed to their mother and father end? When – if ever – might they be allowed to follow their own desire for love and happiness? These contests were largely fought out in the secluded privacy of home – ‘the nunnery’ as one of the princesses bitterly described it – which perhaps made the sisters’ trials less visible than those of their more flamboyant brothers, but they were no less the product of powerful and often disruptive feelings.

These were extraordinary stories in themselves, and ones I longed to tell. But the more I read, the more I was convinced that the experiences of the female royals could really be appreciated only as part of a much wider canvas. The experiences of Charlotte and indeed all her children – the sons as much as the daughters – could not be understood without exploring the personality, expectations and ambitions of the king. It was George III, both as father and monarch, who established the framework and set the emotional temperature for all the relationships within the royal family. And, as I soon discovered, his ideas about how he wanted his family to work, and what he thought could be achieved if his vision were to succeed, went far beyond the happiness he hoped it would bring to his private world.

George was unlike nearly all his Hanoverian predecessors in his desire for a quiet domestic life. As a young man, he yearned for his own version of the family life he thought so many of his subjects enjoyed: an emotionally fulfilling, mutually satisfying partnership between husband and wife, and respectful but affectionate relations with their children. This was an ideal that suited his dutiful, faithful character, and which he genuinely hoped would make him and his relatives happy. But he also hoped that by changing the way the royal family lived, by turning his back on the tradition of adultery, bad faith and rancour that he believed had marked the private lives of his predecessors, he could reform the very idea of kingship itself. The values he and his wife and children embraced in private would become those which defined the monarchy’s public role. Their good behaviour would give the institution meaning and purpose, connecting it with the hopes, aspirations and expectations of the people they ruled. The benefits he hoped he and his family would enjoy as individuals by living a happy, calm and rational family life would be mirrored by a similarly positive impact on the national imagination. In his thinking about his family, for the king, the personal was always inextricably linked to the political.

As I hope this book shows, there were many good things that emerged from George’s genuinely benign intentions. But, as will also be seen, his vision imposed on his family a host of new obligations and pressures. George, Charlotte and their children were the first generation of royals to be faced with the task of attempting to live a truly private life on the public stage, of reconciling the values of domesticity with the requirements of a crown. The book’s title, The Strangest Family, partly reflects the opinions of close observers and indeed of family members themselves that among the royals were to be found some very distinctive, strong-willed and colourful characters; but it also recognises the paradox at the heart of modern monarchy. For most people, the family represents the most intimate and personal of spheres. For royalty, it is also the defining aspect of their public identity. The modern idea of monarchy owes far more to George III and his conception of the royal role than is often realised. His insight did much to ensure the survival of the Crown, linking it to the hearts and minds of the British in ways of which he would surely have approved. But, in other respects, his descendants still find themselves trying to square the circle he created, attempting to enjoy a family life defined by private virtues, yet obliged to do so in the unflinching glare of public scrutiny.

Although the experiences of George, Charlotte and their children are at the heart of this book, I have ranged beyond their stories to include those of their immediate forebears. It is impossible to appreciate what George III was attempting to achieve without understanding the moral world he sought so decisively to reject. In doing so, I was fascinated by the complicated marriage of George II and his wife Caroline (another clever Hanoverian queen), a stormy relationship coloured by passion, jealousy and deceit in fairly equal measure. Their hatred for their eldest son Frederick, operatic in its intensity, still makes shocking reading after so many years. I have also looked forward in time to include in some detail the story of George III’s only legitimate grandchild, Princess Charlotte. Hers is a sensibility very different from that of her predecessors: she was a young woman of romantic inclination, devoted to the works of Lord Byron and given to flirtations with unsuitable officers. The clash of wills between the young Charlotte and her grandmother, the queen, is one in which two very different interpretations of royal, and indeed female, duty collide, with an outcome as unexpected as it is touching.

I did not set out to write a book that ranged so far across the generations and included so many large and powerful personalities. I believe, however, that without that level of scale and ambition, it would be impossible to do justice to the story I wanted to tell. Besides, I have always loved a family saga. That is the narrative that dominates the diaries and correspondence that have been my window onto the reality of eighteenth-century lives. I have tried to use those sources to let the characters in this book speak, as far as possible, for themselves. I like it best when their voices are heard as clearly and as directly as possible. It will be up to the reader to decide if I have succeeded.

Bath, July 2014

Epigraphs

(#u8a55c912-75b5-59cf-82fb-962e986f9e77)

‘But it is a very strange family, at least the children – sons and daughters’

SYLVESTER DOUGLAS, Lord Glenbervie, diarist

‘No family was ever composed of such odd people, I believe, as they all draw different ways, and there have happened such extraordinary things, that in any other family, public or private, are never heard of before’

PRINCESS CHARLOTTE, daughter of George IV

‘Laughing, [she] added that she knew but one family that was more odd, and she would not name that family for the world’

PRINCESS AUGUSTA, mother of George III

Prologue

(#u8a55c912-75b5-59cf-82fb-962e986f9e77)

FORTY-FOUR YEARS AFTER THE EVENT took place that altered his life for ever, George III could still recall with forensic clarity exactly how it happened. On Saturday 25 October 1760, he had set off from his house in Kew to travel to London. He had not gone far when he was stopped by a man he did not recognise, who pulled a note out of his pocket and handed it to him. It was, George remembered, ‘a piece of coarse, white-brown paper, with the name Schroeder written on it, and nothing more’. He knew instantly what this terse and grubby communication signified. It was sent by a German servant of his elderly grandfather, George II; using ‘a private mark agreed between them’, it informed the young man that the old king was dying, and that he should prepare to inherit the crown.1 (#litres_trial_promo)

To avoid raising alarm, George warned his entourage to say nothing about what had passed, and began to gallop back to Kew. Before he reached home, a second messenger approached him, bearing a letter from his aunt Amelia, the old king’s spinster daughter. With blunt punctiliousness, she had addressed it ‘To His Majesty’; George did not need to open it to understand that his grandfather was dead and that he had come into his inheritance. Amelia was probably the first person to call him by the title he would now bear for the rest of his life. With a similarly precise observation of the formalities, he signed his reply to her ‘GR’ – Georgius Rex. When he had set out for London that morning, he was the Prince of Wales, a young man of twenty-two embarking on a day of ordinary business, with no reason to suppose the life of perpetual anticipation and apprehension which he had endured since childhood was about to come to an end. The message contained in that ‘coarse, white-brown paper’ changed all that, turning him into the ruler of one of the most powerful nations in the world. ‘A most extraordinary thing is just happened to me,’ he scribbled breathlessly in a letter he wrote immediately after receiving the news.2 (#litres_trial_promo) He was right. His long apprenticeship was over. He was king at last, and the mission for which he had been preparing himself for so many years could now begin in earnest.

*

The prospects for the new reign looked exceptionally bright. ‘No British monarch,’ the diarist Horace Walpole later declared, ‘has ascended the throne with so many advantages as George III.’3 (#litres_trial_promo) The new king was very fortunate in his timing. Had his predecessor died just a few years earlier, Walpole’s bullish optimism would have been inconceivable. Since the mid-1750s, Britain had been embroiled in a territorial struggle between the monarchies of Europe which, by 1756, had metamorphosed into a conflict of international proportions. During the Seven Years War, in North America, the Caribbean and India, the British fought the French in a clash of would-be global superpowers to establish strategic mastery over whole continents. Things started badly for the British, but with the appointment of the buccaneering William Pitt as first (later known as ‘prime’) minister in 1757, the tide was decisively turned. In the course of a year, the French surrendered valuable sugar-producing islands in the West Indies, lost the Battle of Quebec, which challenged their cherished pre-eminence in Canada, and saw their fleet decisively beaten by the Royal Navy at Quiberon Bay. It was hardly surprising that 1759 became known as ‘the year of victories’. As news of fresh triumphs continued to roll in, even the British themselves seemed somewhat taken aback by the scale and speed of their achievement. When the French capitulated at Pondicherry in 1761, which effectively forced them out of India, Walpole was not sure he could absorb any more success. ‘I don’t know how the Romans did, but I cannot support two victories every week.’4 (#litres_trial_promo)

Britain’s confidence on the international stage was mirrored by a similarly robust sense of self-worth at home. César de Saussure, a Swiss traveller who visited Britain in 1727, was struck even then by the unshakeable sense of pride the British displayed in themselves and all their works: ‘I do not think that there is a people more prejudiced in its own favour than the British people. They look upon foreigners in general with contempt and think nothing is done as well elsewhere as it is in their own country.’5 (#litres_trial_promo) The British had no difficulty in identifying the source of their good fortune: their political liberty, guaranteed to them by birthright and history, and enshrined in a constitutional settlement which protected them equally from the despotism of absolutist kings and the anarchy of the mob. De Saussure observed that the English ‘value this gift more than all the joys of life, and would sacrifice everything to retain it’. Nor was this passionate attachment confined to the political classes. Even the poor, who could not vote, ‘will give you to understand that there is no country in the world where such perfect freedom may be enjoyed as in England’.6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Liberty was not an unmixed blessing, however. Whilst foreign visitors found much to admire in the constitutional freedoms the British enjoyed, they were far more ambivalent when confronted with the impact of these ideas on the mass of the population. The assertive, aggressive, unapologetic behaviour of the urban poor, particularly in London, shocked observers used to more decorous (or more cowed) communities. De Saussure thought ordinary Londoners disrespectful, rowdy and threatening, ‘of a very brutal and insolent nature, and very quarrelsome’. He was horrified by their habitual drunkenness and casual violence, but was most disturbed by their lack of respect for their social superiors. He noted – perhaps as a result of painful personal experience – that a finely dressed man, especially one ‘with a plume in his hat or his hair tied in a bow’, risked verbal abuse and worse if he walked alone through the poorer streets. On holidays such as Lord Mayor’s Day, ‘He is sure, not only of being jeered at and being be-spattered with mud, but, as likely as not, dead dogs and cats will be thrown at him, for the mob makes a provision beforehand of these playthings, so that they may amuse themselves with them on the great day.’7 (#litres_trial_promo)

The energetically expressed opinions of the crowd frequently went far beyond contempt for the sartorial pretensions of the rich. Mobilised in large numbers, the freeborn Englishman was given to demonstrations of popular feeling that were often violent. Issues of political and religious controversy (particularly those which were thought to undermine the dual foundations of British freedom – the Protestant settlement and a limited monarchy) brought men and women on to the streets to make their views loudly known. Throughout the eighteenth century, the threat of disorder and disturbance was as much a part of the life of British politics as the parliamentary vote. As they went about the process of government, the great and the good were abused, threatened and sometimes physically manhandled; parades were staged, effigies burnt, stones thrown, windows broken, carriages overturned, property destroyed; there were injuries and sometimes deaths. The practice of liberty could be a rough business on the streets of George III’s Britain.

If Britain in 1760, was a volatile and sometimes intimidating place, it was also an increasingly wealthy one. Almost every visitor commented on the general air of comfortable prosperity that manifested itself in the clean and well-appointed private houses, the luxurious inns and, above all, in the quality of the roads. Unlike most European highways, these were well engineered and very extensive, linking not just the great cities, but smaller market towns and villages. They were paid for by tolls, and regularly maintained. Foreigners were amazed to discover that travel, such an ordeal everywhere else, had in large areas of England become a leisurely communal pleasure. One bemused observer noted that even on a Sunday evening, the roads outside London were packed with people on the move, visiting, travelling, or simply taking the air. ‘Carriages of every kind … succeeded each other without interruption and with such rapidity that the whole picture looked like magic; it certainly showed a degree of wealth and extent of population, of which one had no notion in France.’8 (#litres_trial_promo)

From the moment of their arrival, travellers to Britain were struck by the sheer busyness of the place. They were astonished by the air of perpetual activity, not just on the roads, but in the teeming streets; in the ports dominated by the masts of tightly packed ships; on the new canal systems, thronged with burdened barges; in the parks and pleasure gardens, where rich and poor mingled in huge numbers in pursuit of a good time. In fact, mid-eighteenth-century Britain had yet to experience the rapid growth in population that would see its towns and cities grow to unprecedented size in the next hundred years. There were around 7.5 million people living in England, Scotland and Wales in 1750. France, a much larger country, supported far greater numbers; in the same year, its population reached 25 million. The universal impression of Britain as a crowded, bustling community arose less from the absolute numbers of its inhabitants than from a far more significant development – the extraordinary size and influence of its capital city.

Although Britain was not yet a heavily populated country, it was already a strongly metropolitan one. London doubled in size between 1600 and 1800; by the end of the seventeenth century, it was the largest city in western Europe. By 1750, only 2.5 per cent of Frenchmen lived in Paris; in comparison, London housed 11 per cent of the population.9 (#litres_trial_promo) An unprecedented proportion of Britons were Londoners, whether by birth or immigration. Still more had some experience of metropolitan life, even if they subsequently left it behind them. It has been calculated that one in six of the population of mid-eighteenth-century Britain had lived in London at some stage in their lives.10 (#litres_trial_promo) The magnetic attraction of the capital was overwhelming, especially to foreign visitors. Most travellers went straight there, and few ventured beyond the southern counties which were already becoming the capital’s dependent hinterlands. Their experiences were dominated by the time they spent in the capital, which shaped profoundly their perceptions of the country as a whole.

The lure of London was not confined to foreigners. Like so many other ambitious young men of the time, James Boswell was convinced that the only proper existence for an eager striver like himself was one lived to the full in London. He could not wait to leave his native Edinburgh behind and embrace all the possibilities London offered. Arriving at its outskirts in 1762, he was beside himself with anticipation, declaring that ‘I was all life and joy!’ As his carriage descended Highgate Hill, ‘I gave three huzzas and we went briskly in.’11 (#litres_trial_promo) It was Boswell’s great patron Samuel Johnson – himself a grateful emigrant from the staid Midlands – who famously linked the appetite for London’s pleasures to the enjoyment of life itself. From his first arrival in town, Boswell did all he could to demonstrate the truth of Johnson’s observation. Subject headings from the index to the London Journal that Boswell wrote during his stay between November 1762 and August 1763 give a taste of the capital’s gamey appeal: ‘Artists exhibitions, billiards, bleeding, Bow St magistrates court, card-playing, catch singing, circulating library, cock-fighting, concert, damning a play, Guards on parade, horseback rides, intrigues, Newgate prison, prostitution, royal menagerie, Mrs Salmon’s waxworks, surgeons and their fees, Tyburn, execution at, watermen rowing for prizes.’12 (#litres_trial_promo)

London’s reputation as the place where anything was on offer and where everything seemed achievable was then, as it is now, the key to much of its pungent attraction. But it promised far more than entertaining diversions. The growth of the capital was driven by the extraordinary number of roles it performed. It was the focus of the nation’s politics. The king lived there, it was where Parliament assembled, and it was there that the political classes expected to fight their battles and win their arguments. At court at St James’s, in the government offices at Whitehall, the debating chambers at Westminster, they planned their strategies and marshalled their supporters; in the conversations of the coffee houses and taverns, in the great mansions of aristocratic grandees and sometimes on the volatile, riotous streets, the successes and failures of their policies were forcibly and mercilessly assessed. London was also a magnet for anyone interested in the making and management of that other great lever of power: money. The capital was home to Europe’s most sophisticated banking system, and to the busiest, most innovative and ambitious financial markets in the world. The wealthy moneymen of the City of London – known derisively as ‘Cits’, whose nouveau-riche antics were ruthlessly caricatured by contemporary satirists – had long overtaken the Dutch as the brokers, bankers and insurers of international choice. But London’s commerce went far beyond the buying and selling of money. It was a thriving market place for the selling of goods as well as services. It was a great port, a major destination for shipping, whose crowded forests of masts packed into the Thames docks astonished foreign visitors and were a striking visual reminder of the other great preoccupation of eighteenth-century Britons: trade.

The whole of Europe benefited from an upturn in international trade in the middle years of the eighteenth century, but no nation did so with such spectacular results as Britain. British merchants dealt in a vast and ever-expanding range of goods. New essentials – such as tea, coffee and sugar – came into the country, whilst a host of exports – from textiles to metalwares to Josiah Wedgwood’s competitively priced china – flowed out.