Полная версия:

Hollow Places

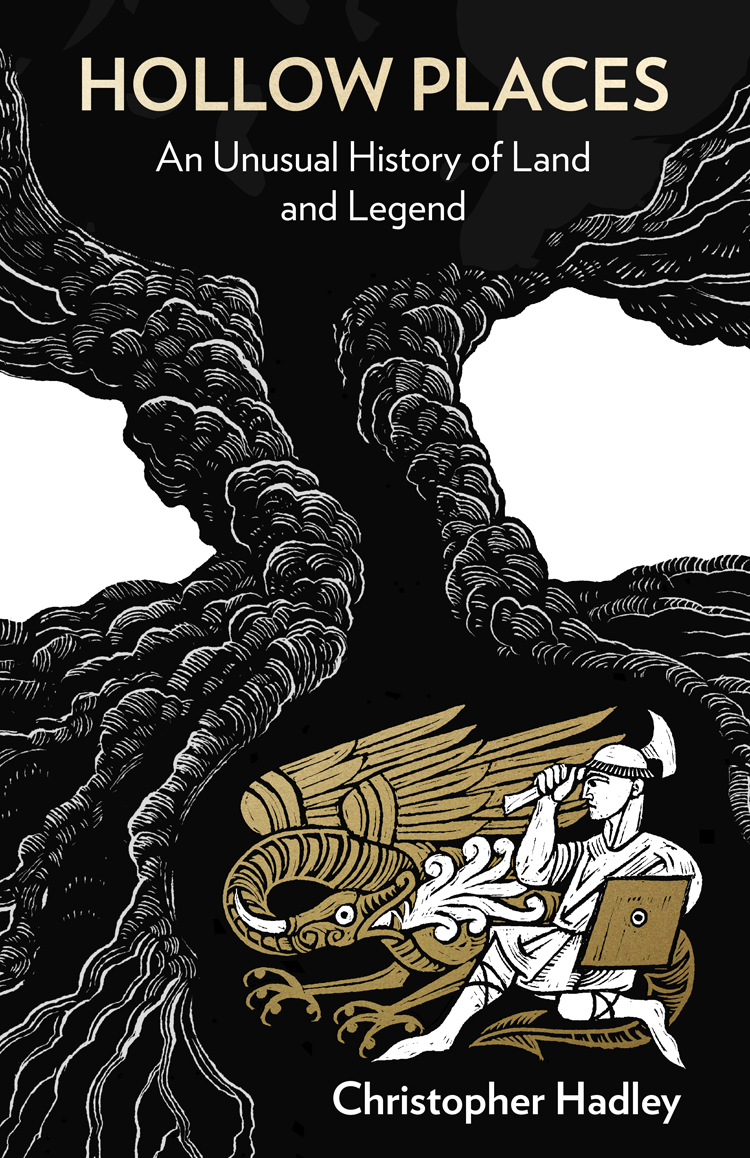

HOLLOW PLACES

An Unusual History of Land and Legend

Christopher Hadley

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright © Christopher Hadley 2019

Cover illustration by Joe McLaren

Christopher Hadley asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008319472

Ebook Edition © August 2019 ISBN: 9780008319519

Version: 2019-06-28

Dedication

To my dad Harry Raymond Hadley, and in loving memory of my mum Joan Mary Hadley, a born storyteller

Epigraph

Dummling set to work, and cut down the tree; and when it fell, he found in a hollow under the roots a goose with feathers of pure gold.

—‘The Golden Goose’ in German Popular Stories, collected by Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm, from oral tradition, London, 1823

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Part I: Tree

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Part II: Stone

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Part III: Story

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Part IV: Name

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Part V: Last Things

Chapter 33

Chronology and select textual history

Notes

List of illustrations

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

THE SHONKS EPITAPH, BRENT PELHAM. — I should be grateful for information regarding the epitaph on O. Piers Shonks in Brent Pelham Church, Hertfordshire. The tomb of this worthy lies in a recess cut into the north wall of the church and bears the following inscription in Latin (I quote from memory):—

Tantum fama manet Cadmi Sanctique Georgi Postuma; tempus edax ossa sepulchra vorat.

Hoc tamen in muro tutus qui perdidit anguem Invito positus Daemone Shonkus erat.

There is also a neat rhyming translation in English which I cannot recall.

Who was Shonks? What is the point in the reference to Cadmus and St. George (in itself a curious conjunction of names)? What is the significance of ‘who destroyed the snake’ (the Devil?) as applied to Shonks? What is the point of ‘invito Daemone’?

I understand that a field in the village still bears the name ‘Shonks’ field.’

D. C. THOMPSON.

Notes and Queries, 1932

In the High Middle Ages, on the Hertfordshire–Essex border, a remarkable tomb was carved out of grey-black marble to cover the bones of an English hero whom legend calls Piers Shonks. For centuries, tales about dragons, giants and the devil have gathered around the tomb and spread into the surrounding countryside. How and why that happened is the subject of this book: it is both a historical detective story and a meditation on memory, belief, the stories we used to tell – and why they still matter.

I begin on the edge of Great Pepsells field on a cold winter’s morning in the early nineteenth century.

LITHETH AND LESTENETH AND HERKENETH ARIGHT

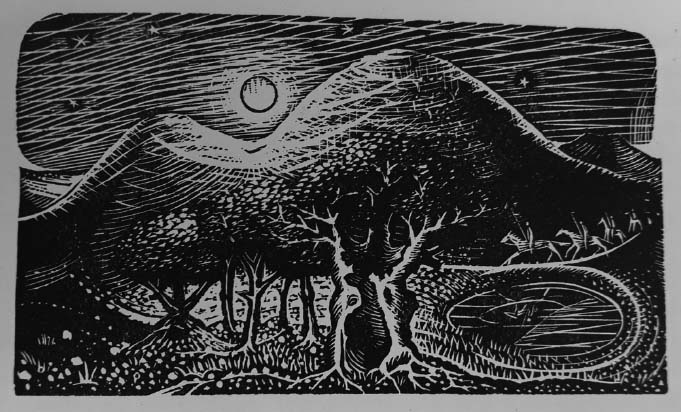

She was the oldest living thing thereabouts.

Alone, on the wide plateau between the rivers Ash and Quin, the old yew tree had stood since time out of mind and beyond the memory of man.

Did old Master Lawrence think of her great age when he tested the cold edge of his felling axe that winter’s morning? He would have known that bringing her down was going to be an ’umbuggin job, but he had no idea how things would turn out; that before the day was over he and his axe would become part of a story already ages old. Two hundred years hence, people would still be talking about the yew in Great Pepsells field, of the day she fell and of what the woodcutters found in her roots.

For some twenty years now she had stood alone: resolute but incongruous in that heavy-clay field where tracks and parishes met; her evergreen boughs prey to lightning, the knots and sinews of her trunk rivened by wind and hail. She had once marked the northernmost boundary of a wood, but the acres of ash and maple had been grubbed up in the years between Trafalgar and the death of Old Boney.

Perhaps the landowner, or his steward, had left her standing for her grandeur. Generations must have paused to admire her or sheltered beneath her thick crown. Children, dallying on their way to gather brushwood or flints or rushes, would have carved their names in her bark and picked her blood-red arils – breakfasting on the bitter flesh and spitting the poisonous seeds to the ground.

The tree stood in the village of Furneux Pelham, 500 yards from the parish boundary. Half a mile further east across the level fields rose the tower and Hertfordshire spike of St Mary the Virgin in Brent Pelham. That the church was the only building in sight is not incidental, nor was the presence of yet another parish boundary just 200 yards to the west along the widening ditch: strange things happen where three parishes meet.

There she grew in this remote spot near the Hertfordshire–Essex border, within five or six feet of where a Roman road lay beneath the soil of the field. (Did her shadow once fall on the Eagle of the Ninth?) Trees of that age – like the famous churchyard yews at Tandridge and Crowhurst in Surrey – have many textures: on one face she might be red and hairy and corded, a trunk of immense ropes twisted into terrible strength, yet on another, bleached and moth-eaten, misshapen like driftwood. From certain angles, in certain lights, vermicular, flayed, mutating.

She had grown into a storybook tree, long before she became part of a story.

They say that she had ‘split open, as such trees do, with extreme old age’. A great wound. Split enough and large enough to have a stile and steps set in her trunk. The Reverend Soames, pursuing rumours of piglets or turnips (one in every ten was his), might easily follow the track across Pipsels Mead and Nether Rackets, through the great tree into Pepsells, and on through Long Croft or Lady Pightle towards Johns a Pelham Farm.

Was she as prodigious as the yew at Crowhurst with its small door set in its hollow trunk? Or more wonderful still? Like the greatest of all surviving British yews at Fortingall in Perthshire. Once fifty-six feet round there was plenty of space between her trunks through which to lead a horse and cart. Today, both trees are thought to have taken seed in the reign of the Emperor Augustus.

Was the Pepsells yew already centuries old when Peola gave his name to Peola’s-ham, the homestead that became Pelham? Did the militia enter the village butts with longbows from her boughs? Did a Saxon, a Roman, a scout from the Trinovantes tribe 2,000 years ago take his bearings from her? Generations pass while some trees stand, and old families last not three oaks. Nor one yew.

Master Lawrence, the woodcutter, was unlikely to think of these things. He would have thought of village stories. Perhaps of poor Widow Bowcock stabbed to death in the fields thereabouts in the last century, or the handles of grubbing axes broken in the heavy ground when clearing the roots from Ten Acres Field to make way for barley; of tall tales told by old men as they coppiced the hornbeam to make charcoal on a morning such as that one; tales about the black tomb in the church wall and the man called Shonks who sleeps in it, about his winged dogs, the monster they killed and the immense double-jointed finger bones that gave Mr Morris so much trouble.

Master Lawrence heard from the pulpit on the first day of Lent that cursed be he who removeth his neighbour’s landmark. He may have fretted that his first job that winter’s morning was to bring down such a singular tree. A landmark, which they of old time have set. Might he pay more heed to an old wife’s ‘no-good-will-come-of-it’? Perhaps there was little room in such a life for superstition. I think he pulled his stockings up to meet his breeches in the light of the hearth and rush-light and thought that his business was no one else’s concern, turning his mind instead to how hard the ground was that morning – yet not as hard as yew wood from which he might fashion axle pins or mill cogs. A practical man who kept his concerns to himself. After the event, I don’t suppose he would have had much truck with foolish enquiries about a morning’s work.

Gone, the merry morris din

Gone, the song of Gamelyn.

And yet years later he would talk about the ordeal of felling that tree – and the ‘girt hole underneath it, underneath its roots, a girt cave like’ – and in this way the simple woodcutter became as important to this story as the stonemason had 800 years earlier, no less important than the map-maker, the fundamentalist, the poet and all those who are caught in its weave.

It is the early 1830s: a time of great change. The sailor King William IV is on the throne, a young Charles Dickens has begun writing under the pen name Boz, Charles Darwin is on board HMS Beagle, and in a Hertfordshire village Master Thomas Lawrence and a gang of farm labourers are about to find a dragon’s lair beneath the roots of a tree.

1

The Reader will rather excuse an unsuccessful Attempt to clear up the Truth where so little Light is to be had, than giving Things up for nursery Tales to save the Pains of Inquiry.

—Nathaniel Salmon, The History of Hertfordshire, 1728

I like to know where dragons once lurked and where the local fairies baked their loaves, where wolves were trapped and suicides buried, who cast the church bells, which side the Lord of the Manor took in the Civil War and which modern surnames were found in the first parish register (and which in the records of the assize). I am with Walter Scott, who was ‘but half satisfied with the most beautiful scenery if he could not connect it with some local legend’. To map a place and to know its stories is to belong, to find companionship with the living and the dead, to time-travel on every visit to the Brewery Tap or the Black Horse. Sometimes you spot something – a burial mound, a scratch dial in the church porch – and then set out to find its story. Other times you hear a story and go in search of it in the landscape, or the archive or someone’s memories, and that is how my journey to Great Pepsells field and the spot where Master Lawrence felled a yew tree began.

I first encountered the name Shonks some years ago on the Pelhams’ website. Piers Shonks, a local hero, was buried in a tomb in the wall of the church in Brent Pelham. Apparently, he was a giant who had slain a dragon that once had its lair under a yew tree in a field called Great Pepsells. As one rustic supposedly said, ‘Sir, it’s one of the rummiest stories I ever heard, like, that ’ere story of old Piercy Shonkey, and if I hadn’t see the place in the wall with my own eyes I wouldn’t believe nothing about it.’

To know Shonks is to wander the margins of history: the margins of the Bayeux Tapestry where strange creatures gather, the margins of ancient woodland where hollow trees hide secrets, of eighteenth-century manuscripts where antiquaries have scribbled clues to the identity of folk heroes. It is to encounter the many other folk legends we find around the country: stories about dragons and giants and devils, avenging spirits and outlaws, which all have their echoes in the legend of Piers Shonks. It is to rediscover a world where the community was in part defined by its collective memory, by its pride in its past, and a story its members had passed down through the generations: to wrestle with their superstition, what they really believed and what that tells us about them, their priorities and their needs (and about us too for that matter, how we are different and how very much still like them).

To know Piers Shonks is to sit shivering in a church in Georgian England sketching the dragon on his tomb, to stand atop its tower triangulating the Elizabethan countryside, and to confront the zealous Mr Dowsing and his thugs looting the brasses and smashing the masonry during the Civil War. It is to ask why Churchwarden Morris could not sleep at night, and how long bones last in a crypt, and where a medieval stonemason found his inspiration. It is to wonder what a thirteenth-century tomb is doing in the wall of a fourteenth-century church, who is really inside it, and why he was immortalised by generations of storytellers.

At first, and for many months, to know Piers Shonks was to wonder that less than 200 years ago some farm labourers supposedly uncovered a cave under a tree in a field where a centuries-old folk legend said that a dragon had lived. Did they really? Surely not. This is where people usually wrinkle their brow. ‘You’re writing a children’s book?’ they ask.

No, it’s a history book, a historical detective story … People generally look confused at this and then venture: ‘Oh, it’s a novel.’

It’s non-fiction, I explain.

‘But no one really found a dragon’s lair under a tree.’

Maybe not, I concede, but they believed they did.

‘They didn’t really.’

I think they did.

‘Really?’

This book began with that question, and in trying to answer it I discovered things even more puzzling, things that eventually brought home to me the importance and the power of the folk legends we used to tell and why they still matter. The story of Piers Shonks is not the legend that changed the world, it did not forge the nation or launch a thousand ships. It is an obscure tale, of small importance, but it has endured: the survivor of an 800-year battle between storytellers and those who would mock or silence them. Shonks’ story stands for all those thousands of forgotten tales that used to belong to every village.

This rumour of a tree that once housed a dragon caught my imagination, as the tree itself must have bewitched those farm labourers. It took root and grew, putting out feelers, tapping the furthest horizons of my mind, where the magical and mysterious lay buried, becoming a solitary and crooked shape in a field far away from a winding road, both sinister and oddly pleasing. Perhaps frightening and anatomical in silhouette, with claws like the tree at the bend by Jack’s Bridge as you enter the village at dusk, but much larger and more substantial: Girth enourmous like the Yardley Oak in Cowper’s poem, with ‘moss cushion’d root / Upheav’d above the soil, and sides emboss’d / With prominent wens globose’, a shatter’d veteran, hollow-trunk’d, embowell’d, and with excoriate forks deform. Cowper, the great Hertfordshire poet of nature, has appropriated all the right adjectives for the job.

I hoped, rather ridiculously, that I could somehow identify the tree on old maps. An early estate map of the Pelhams has lovely water-coloured woods and springs of trees with shadows pooling to the east, but no individual trees. The Ordnance Survey followed the same convention, so that the sun is always setting in nineteenth-century mapscapes, but whereas the earlier maps showed trees merely to indicate the presence of woodland, the second half of the nineteenth century saw the arrival of OS maps so detailed that they showed every non-woodland tree in fields or hedgerows that was more than thirty feet from another tree. Oliver Rackham, the historian of the countryside, estimated that nationwide the surveyors plotted some twenty-three million individual trees, and many are still there to be found.

While single trees were marked on the published maps, single tree stumps might be plotted on the original boundary sketch maps because they were meres marking the beginning and end of a hedge that the farmer had uprooted half a century before. I once spent an enjoyable hour searching for the vestiges of the ‘Hornbeam Stub’ that marked a stretch of boundary between Furneux Pelham and Great Hormead. My search was in vain, as it was for the yew tree. Sadly, as I later learned, Master Lawrence’s axe had struck the yew some forty years before the first large-scale sheets of north-east Hertfordshire. Still the looking was almost as rewarding as the finding would have been.

The tree was just the start. I was soon fascinated by the tomb in the wall, the inscription above it, and other places associated with the hero: Shonks Garden, his wood, and his moat. At first, I kept coming across intriguing references to Piers Shonks when I was looking for something else: in old newspapers and county histories, guidebooks and letters. He was even in the old Post Office directories: at Brent Pelham in 1862 with its reported 1,601 acres and population of 286, I read that in the church ‘In the north wall of the nave there is a curious monument to the memory of one Piers O’Shonkes, the legendary slayer of dragons’.

Ever since the Elizabethan map-maker John Norden passed through Brent Pelham and found the place name and Shonks’ tomb the only things worth noting down, people had been trying to get to the bottom of the legends attached to that curious monument. In the words of the eighteenth-century antiquary and tombstone enthusiast Richard Gough – pretending to disapprove – the tomb had long ‘furnished matter for vulgar tradition, and puzzled former antiquaries’.

Folklorists collect things. Fully paid-up folklorists might collect legends associated with a place, such as those who compiled the Folklore Society’s classic county series. Others focus on a theme such as the folklore of plants, some collect fairy-lore, playground chants or dances.

For my part, I found myself simply collecting the legend of Piers Shonks; that is instead of just happening upon accounts of the legend, at some point I started hunting for them. In the preface to his Italian Folktales, Italo Calvino describes perfectly what this is like, the sometimes obsessional searching, his feeling that some ‘essential, mysterious element lying in the ocean depths must be salvaged to ensure the survival of the race’. At the same time, he knew that there was a risk of disappearing into the deep. ‘I was gradually possessed by a kind of mania, an insatiable hunger for more and more versions and variants. Collating, categorizing, comparing became a fever.’

As I spent ever more time in the company of Shonks, I liked to seize on anything that helped me to justify it, not least the notion that along the way I would learn a thing or two about something worth knowing about. In her 1914 The Handbook of Folk-Lore, Charlotte Sophia Burne suggests that studying ‘folk-lore’ will advance the study of ethnology, history, economics, politics, sociology and psychology. There are certainly worse ways to get your bearings in an English village than to study its old stories, examine its tombs and dig up its potsherds. The father of antiquaries, Joseph Strutt, wrote that the study of such things ‘brings to light many important matters which (without the study) would yet be buried in oblivion, and explains and illustrates such dark passages as would otherwise be quite unknown’.

That sounds like a suitably gothic enough reason for us to go in search of Piers Shonks. And where better to start than at the house that Shonks built?

2

And as imagination bodies forth / The forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen / Turns them to shapes, and gives to airy nothing / A local habitation and a name.

—A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act 5, Scene 1

On a summer’s afternoon in the early years of the twentieth century, a group of Edwardian gentlemen processed through a field of close scrub in Brent Pelham like men who had lost something important. The ground was unremarkable, broken and tumbled down to woodland, but was bound by wide and now stagnal ditches dug with great effort some seven or eight centuries earlier to fashion a moat. The members of the East Hertfordshire Archaeological Society were searching for signs of a half-remembered house that had once stood there, but I hope that some among them were looking for something more, hoping to catch sight of a great rumour in its infancy, to detect, in a broken blade of grass perhaps, the long-ago path Piers Shonks took on the day legend says he bested a dragon.

See you the dimpled track that runs,

All hollow through the wheat?

O that was where they hauled the guns

That smote King Philip’s fleet.

Rudyard Kipling’s ‘Puck’s Song’ didn’t appear in print until the following year, but the archaeological imagination it embodies was no doubt at work that summer’s day in 1905 as those men tried to find something hidden beneath tussock and root that would carry them back to the distant past.

A local newspaper report of the day’s excursion called it ‘a moated site of some two and a half acres across upon which once stood the castle of the celebrated Piers Shonks, the slayer of the Pelham Dragon’. The castle (if not the dragon and its slayer) was a fiction. Most moats that trench the countryside are not the stuff of medieval sieges, but are homestead moats built around new farms and manor houses in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries by men ostentatiously proclaiming their independent status and their membership of the knightly class – or their aspirations to it. They were especially popular on the boulder clay of East Anglia. Oliver Rackham has written that anyone who has dug as much as a posthole in the clay will be in awe of the labour that went into excavating an entire moat, so people must have had a good reason to do it. They may have served a practical purpose as fishponds, or as a ready water supply for putting out fires, or for drainage or sewerage, and they must have offered some degree of deterrence to passing robbers and rapists, the notorious trailbastons – vagabonds with big sticks – of the period, but many historians agree that moats were first and foremost a status symbol.