Полная версия:

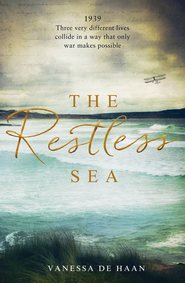

The Restless Sea

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Copyright © Vanessa de Haan 2018

Cover photographs © Mark Owen/Trevillion Images (seascape); © Shutterstock.com (letter and plane)

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Vanessa de Haan asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it

are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead,

events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008245764

Ebook Edition © April 2018 ISBN: 9780008229818

Version: 2018-01-23

Dedication

To my weird, wonderful and extensive family

– you know who you are –

and to Amelia Grace Jessel, in memory.

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Hymn

Prologue

Chapter 1: Jack

Chapter 2

Chapter 3: Charlie

Chapter 4

Chapter 5: Olivia

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8: Jack

Chapter 9

Chapter 10: Charlie

Chapter 11

Chapter 12: Olivia

Chapter 13

Chapter 14: Charlie

Chapter 15: Olivia

Chapter 16: Jack

Chapter 17: Charlie

Chapter 18: Jack

Chapter 19: Olivia

Chapter 20: Jack

Chapter 21: Charlie

Chapter 22: Jack

Chapter 23: Charlie

Chapter 24: Olivia

Chapter 25: Jack

Chapter 26: Olivia

Chapter 27: Charlie

Chapter 28: Olivia

Chapter 29: Charlie

Chapter 30: Olivia

Chapter 31: Jack

Chapter 32: Charlie

Chapter 33: Olivia

Historical Note

Acknowledgements

We, Who Live Now

About the Author

About the Publisher

Hymn

Eternal Father, strong to save

Whose arm does bound the restless wave

Who bidst the mighty ocean deep

Its own appointed limits keep

O hear us when we cry to thee

For those in peril on the sea

O ruler of the earth and sky

Be with our airmen as they fly

And keep them in thy loving care

From all the perils of the air

O let our cry come up to thee

For those who fly o’er land and sea

O Trinity of love and might

Be with our airmen day and night

In peace or war

Midst friend or foe

Be with them wheresoe’er they go

Thus shall our prayers ascend to thee

For those who fly o’er land and sea

This famous hymn, written by William Whiting in 1860, is also known as the Navy Hymn and sung at naval occasions around the world. This is a version frequently used by the Fleet Air Arm.

Prologue

The roof stretches across the railway station like the skin of a drum, magnifying the sounds: the tapping and pounding of feet, the trains clanking, the rumble of wheels, the shout of a guard, the whistle of a porter. At the ticket office, there is no sense of where the queue ends or where it begins. A man bashes on the glass, his voice raised in anger, frustration. Tickets are scarce. Everybody here wants to get away, to follow the children who have been evacuated to safer parts of this now unsafe country. The air is sticky and humid. In the haze, little things stand out: two sailors balancing on a stack of cases, one singing as the other accompanies him on a squeezebox. The drifting smoke from the newspaper seller’s pipe; the neat rows of black-and-white print on his stand. A cluster of soldiers, their uniforms smart, the leather of their boots supple and clean, their dark, heavy rifles pulling at their shoulders.

A policeman tails a group of suspicious-looking lads that trickle away from him like mercury, slipping through gaps that close as quickly as they open. He loses them again as they circle a girl dressed in a pale-green coat, a cerise ribbon tied around her matching hat, a bright splash of colour among the drab browns and greys of suits and caps. The policeman glimpses the lads once more as they sidestep the expensive leather cases at the girl’s feet. Then they are gone again, like the brief flash of the bracelet she is fiddling nervously with beneath the cuff of her jacket: now you see it, now you don’t.

The sounds swirl into one cacophony – the sobs of children, the wails of babies, the tinny squeezebox and the guard shouting into the loudspeaker, the scream of another train pulling free from the throng and towards the light. And then suddenly all noise is drowned out by a new sound, one that Londoners will soon grow accustomed to, but this is the first time they have heard its ear-splitting warning. For a moment, the station freezes, caught in a sliver of time. The babies stop wailing. The man stops banging the window. The squeezebox exhales with a breathless sigh. A thousand pairs of eyes widen, a thousand hearts stop beating.

And then there is chaos. Hands fly up to ears. People scream and clutch at each other. Others gape, bewildered. ‘It’s the gas!’ ‘A bomb!’ ‘They’re coming!’ Some people throw themselves to the floor while others blindly follow each other, staggering from one foot to the other, unsure which way to run. People fumble for their gas masks, trying to remember the drill. The straps pinch and catch at their hair; the rubber digs into their faces; the horrible smell fills their nostrils.

The crowd takes on a life of its own and surges towards the Underground, sweeping everything before it, pushing aside anything that will not join the plunging wave. The girl in the pale-green coat is caught up in the rush. She stretches out for her luggage, but it has scattered and she is knocked one way and shoved another and then swept along for a little while, all the time trying to reach back with a pale hand for her bags. The policeman is too busy trying to calm the uncalmable to notice that the girl has been swept up by the hoodlums he had his eye on. Now her bags are lost, but at least she has been carried on the tide to the safety of the Underground.

The siren wails through the empty station. The concourse is a mess of scattered things. Luggage is strewn across the floor like flotsam, bags split open, a favourite teddy has been trampled, the newspapers have toppled to the ground, the thick headlines declaring war smudged and smeared by a myriad of shoes. The ticket seller cowers beneath his desk. The guards and porters have disappeared. The only sign of life is a group of naval ratings who have remained on their platform and are being lined up by a young officer. The officer issues his instructions and smooths his impeccable uniform. The boys do not take their eyes off him, drawing confidence from his easy manner, the authority borne of fine breeding and education. They form neat rows of bell bottoms and white-topped caps. The officer calls out another command, and this time the words echo clearly across the silent emptiness. The wailing has stopped.

The alarm is a mistake, a faulty air-raid siren. The station begins to fill up as people return to search for their lost companions, their abandoned luggage. Soon it is as if the concourse never emptied. The ticket seller clambers up from the floor, dusting the dirt from his trousers and resetting his cap upon his head. A new customer bangs at the window while the people behind him jostle for their original positions in the reformed queue. The policeman has long lost his intended targets. No doubt more will be along any moment. Pickpocketing is as much a problem today as it has always been in these crowded places, and the chaos of a war is not going to help matters. He spies the girl in the pale-green dress grappling for her bags and goes to help, his hand resting on his truncheon, his chin sweaty beneath its strap. Together they count the bags. None is missing. Now another figure emerges from the crowds, small and bird-like beneath a thick fur stole – the only one to be seen in such weather. The girl reaches out to her mother, and the policeman summons a porter to place the bags on a trolley, then touches his helmet in farewell as the porter relays the lady, the girl, and their luggage towards the sleeper for Inverness, skirting around a jumble of bicycles, freight, prams and trunks.

The sleeper is already at the platform. Men are rubbing cloths over its black and maroon paint. The girl and the lady search for the correct carriage. Further along the same platform, the young naval officer is ushering the ratings into the dining car, the only carriage with any space left. The boys chatter and laugh as they jostle for a seat until the officer reminds them that they are representing His Majesty’s Naval Service, and they stifle their smiles behind their hands. Three pregnant women heave themselves into another carriage. A child cries, snotty hiccups that she tries to blow into a handkerchief. A toddler holds her other hand, sucking bleakly at his free thumb. Passengers already on the train lean out of the windows, hands grasping like sea anemones for a last touch of friends and family. One of them is the girl in the pale-green dress, but the woman she has left on the platform has already issued a brief goodbye and turned on her heel, and there is nothing to do but retreat reluctantly into the safety of her compartment.

There are fewer people on the platform now, more guards and porters in their dark-blue uniforms, polished buttons and cap badges glinting. The doors slam and slide. The guard blows his whistle, and there is the whoosh of steam, and slowly, slowly the train starts to move. A woman with puffy red eyes runs alongside, trying to catch a glimpse of a friend or child slipping away. A guard manages to grasp her by the shoulders and hold her back. Someone screams, but the sound is drowned out by the train’s whistle. The carriages jerk forward, away from the confines of the hot and crowded station and out into the warm light. In the dining car, some of the boy seamen are already resting their heads against the windows, eyelids drooping, while others play cards or elbow each other and giggle when they think no one is looking. Their officer adjusts his tie and then runs a finger over the golden wings stitched on to his sleeve and smiles to himself. In the sleeper berth, the girl in the pale-green dress runs her hand over the starched white sheets and sighs. Outside, London begins to slip by faster and faster as the train gathers speed, past narrow gardens and rows of houses, the sun reflected in their windows, making it seem as if the city is on fire.

CHAPTER 1

Jack

The boys tumble out of the station and on to the streets, laughing as they go. It is warm out here, but the air is fresh, and they enjoy the feel of the sun on their skin and the space to move away from the crowds. They follow the tallest of the boys, Stoog, a skinny, athletic-looking lad with hooded eyes and a pent-up energy like a coiled spring. He hustles along a line of people waiting to go in to the cinema, knocking a man’s hat to the ground. ‘Hey! What do you think you’re doing?’ shouts the man, shaking a fist, but the boys don’t care. They laugh and run faster until they finally reach the river and stop to catch their breath.

It is high tide. In the afternoon sun the Thames gleams amber. The boys lean over the railings and watch the ships as the water slaps at the wall below. The shimmering expanse is as busy as the crowded streets behind them. Along the opposite bank a row of Thames barges, their sails neatly furled, swing and turn together on the tide. Sturdy tugs shoulder through the flow, hiccuping black smoke as they go, while another barge tacks across the running river, her dusky red-brown sails flapping and cracking in the wind. Motorboats carve their way past dredgers. The smell of river mud mingled with coal smoke, sewage, oil and tar is as familiar to the boys as the smell of their own mothers.

Stoog is the only one who doesn’t lounge lazily against the rails. Instead, he prowls up and down the pavement. ‘Come on, then,’ he says. ‘Show us what you’ve got.’

The boys turn, leaning back against the metal and digging into their pockets. They casually pull out a variety of watches and wallets, a lady’s purse, a gold watch chain. Stoog nods down the line, until he reaches Jack.

Jack keeps his hands plugged deep in his trousers. He can feel the bracelet, the smoothness of the pearls under his fingers, the cooler sharpness of the sapphire surrounded by winking diamonds. It is the most expensive thing he has ever held, more valuable than a year’s worth of wallets and watches.

‘Go on, then,’ says Stoog.

Jack shakes his head, gripping the bracelet more firmly in his fist.

Stoog steps closer. ‘Go on.’

‘Not this time,’ says Jack.

‘It’s off my patch.’

‘It’s not your patch. We all work it.’

‘You work it because I let you.’

‘I can work anywhere I want.’

‘And who’s going to sell it on for you?’

‘You don’t own this city, Stoog.’

Stoog takes a step towards him, his eyes narrowed. ‘Is that a challenge?’ he says.

‘What if it is?’ says Jack, and he takes a step sideways, dodging the hand as it darts towards him. He legs it without looking back, Stoog’s curses ringing in his ears, leaving the rest of the boys standing there, open-mouthed. Jack is the only one who would dare question Stoog, but they all know that they never get a fair price. Well, if Jack’s going to take one last risk like this, he wants it to be worth it.

Jack has already reached the other side of the bridge, but Stoog is not far behind and Jack knows that he won’t give up easily. He forces himself on, down towards Tooley Street. This is his territory, where he was born and brought up. But it’s Stoog’s too, and sure enough, Jack can hear the ragged breath of the older boy closing in. His only chance is to get to somewhere Stoog can’t follow. But he is still a long way from the docks.

He hears the familiar swish of trolleybuses swinging along on their cables. Even better, there is the tail end of a queue, and a vehicle is beginning to pull away from the stop. He lunges and swings up on to the platform, bending double to catch his breath and grinning at the sight of Stoog receding into the distance.

The conductor’s legs come into view, and Jack takes his time to right himself. He is panting and his legs are shaking. He pretends to fumble for loose change, but the conductor knows his type and is shaking his head and getting ready to see Jack off at the next stop. And now Jack can see another trolleybus close behind, and he knows that Stoog will be on it.

Jack is already down and running again. The docks are within reach. But Stoog is after him, reinvigorated too. Passers-by jump out of the way. Jack is fast, but Stoog is gaining. Now Jack can see the entrance to the docks, and he is almost there, and he finds the strength from somewhere, urging his legs to move, and his chest is about to burst and the breath is burning in his lungs.

He dodges the new sentry, posted fresh this week in case of Nazi invasions. Stupid guard isn’t even looking in his direction, but the man does catch sight of Stoog, which makes Jack smile again. But the sentry can’t stop Stoog: the older boy shakes him off and is now yelling Jack’s name, and pushing past bemused gangs of dock workers. Jack begins to wonder whether he’s made the right choice. Carl isn’t going to be happy. Carl’s dad even less so.

Although it is evening, the docks are still in full swing: there is always cargo for the lightermen to deliver ashore or for the stevedores to load carefully into holds. There is such a tangle of masts and funnels, cranes and ropes that it is hard to determine what is river and what is dry land. Dockers and sailors whistle and shout to each other, struggling to be heard above the whir and grind of machinery, the bump and clatter of barges, and the splash of the water. Jack has the advantage of surprise, being the first runner, but the gathering crowd soon closes up on Stoog. Dockers don’t take kindly to outsiders. Stoog is swearing and wriggling, but he is no match for men who spend their days hauling and heaving freight.

‘Stop that bloody thief!’ Stoog is shouting. And now hands are reaching for Jack too, grasping fingers with torn, black nails, knuckles stained by tobacco. He tries to dodge, but he is tiring. He manages to pull away once more, jinking down behind the metal feet and runners of one of the large cranes and then between a stack of crates. He is alone, but it won’t be for long. His brain is working at high speed, his eyes processing in double-time. There is a wooden shack. He twists into it before his followers around the corner. It is a risk he has to take; he cannot push himself any further.

He is in a putrid darkness. The air is close, the stench makes him gag. He hears the crowd approaching, Stoog still shouting his name. His heart hammers in his chest. The footsteps draw nearer. He presses himself into the inkiest of shadows, the bile filling his mouth as the smell infests his nostrils. The door swings open and a ray of light picks out the pole suspended above the trough of muck. Jack holds his breath and shrinks into a ball. He hears the scuff of boots on the ground, senses the energy of the crowd.

Then his heart lurches. Something shifts in the gloom. He is not alone.

His companion moves to block the door, a large, impassable, barrel-chested shape.

‘There’s a lad on the run,’ says one of the pursuers. ‘You seen anyone?’

A low voice growls back: ‘Can’t a man take a shit in peace?’

Jack’s knees are seizing up, but he does not dare move. The man stands at the door, and the crowd mutters and moves away, the shadows through the slats of the shack darkening and lightening as they go. They drag Stoog with them, still kicking and biting.

Jack collapses to the filthy floor and retches.

The crowd has gone, and now the creak and crunch of the cranes fills the air once more, the sound of foremen shouting their orders and the trolleys and trucks rumbling past. The man at the door steps out into the light. ‘Come on,’ he says. ‘Let’s be seeing you.’

Jack has no choice but to follow. Even though the air outside is still fetid with the stink of the river, it is nothing compared to the latrines. And now there is also the faint, sweet scent of cut wood, for Surrey Docks is a timber dock and there are planks piled in every corner, huge logs bumping and rolling against each other in the water, packed on to the narrowboats that wait on the canal, even swinging above their heads.

Jack eyes the man warily. ‘Why didn’t you turn me in?’ he says.

The man shrugs. ‘You want to watch yourself with those dockers,’ he says. There is a tear in the arm of his shirt that reveals the striking colours of blue and green tattoo ink on his skin. Great patches of sweat have stained his armpits, and even the creases of his face are ingrained with grime.

‘I can handle it,’ says Jack. ‘My dad and my brother both worked the docks.’ His legs have stopped trembling and he pulls himself up straighter, squares his chin.

‘And where are they now?’

‘Fighting the Jerries.’

‘Sorry to hear that.’

‘I’d be doing the same if I was old enough.’

The sailor shakes his head. ‘What are you? Fifteen? Sixteen? Give it a couple of years and you’ll be squeezed into a uniform too; sent off to the knacker’s like those carcasses we bring in to the Royal Docks.’

‘I’m no coward.’

‘What are you running from, then?’

Jack looks at his feet. ‘Nothing. A misunderstanding.’ He feels the weight of the bracelet in his pocket and colours.

The sailor sighs, his cap lifting as he scratches the back of his head. ‘You want to steer clear of a lad like that,’ he says. ‘He’s got a badness about him that ain’t going to lead nowhere good.’

‘Does it look like we’re friends?’

‘It looks to me like you is on the edge. One push and you’ll end up just the same.’

‘I’m different. He doesn’t want me working here, but that’s what I’m doing from now on.’

‘I ain’t talking about working here, boy. Just as I ain’t talking about signing up to another man’s war. I’m talking about freedom. Changing your destiny. Choosing your own path. I’m talking about the ships.’

‘Ain’t that just swapping one uniform for another?’

The man roars with laughter, youthful eyes bright beneath his tattered sailor’s cap. ‘I don’t mean the Navy, boy. You want to be a merchant seaman. No one telling you what to do except for your own kind.’

‘But I ain’t never even been on a boat.’

‘Ent nothin’ to it. Listen.’ The man leans closer. ‘I was like you once, except I had no ma or pa, not a penny to my name. I slept in ditches and drains until I was eight, and then I found myself a berth. Now I’ve sailed to every country you can think of and plenty you can’t. I’ve seen wonders you’d never imagine: beasts of the ocean, castles in the sky, men that breathe fire, women what change shape. I’m free to work when and where I want. Hell, I’ve even got me own stash of gold.’

And he laughs and his great jaw opens, and Jack can indeed see the yellow metal glittering in the back of his dark mouth.

Jack shakes his head. ‘There’s my mum, my sister …’

The man is suddenly serious again, urgent. He thrusts his face right up against Jack’s, and Jack can smell the tobacco on his breath. ‘I can see you’re a brave lad,’ he says, ‘but it takes a proper kind of bravery to turn your life around.’