Полная версия:

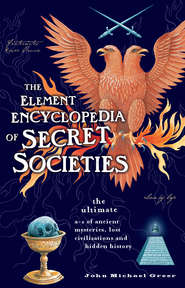

The Element Encyclopedia of Secret Societies: The Ultimate A–Z of Ancient Mysteries, Lost Civilizations and Forgotten Wisdom

The Element Encyclopedia of Secret Societies

John Michael Greer

the ultimate

a-z of ancient mysteries, lost civilizations and forgotten wisdom

Dedication

On a spring afternoon some years ago, as I waited in the anteroom of an aging lodge building for my initiation into one of the higher degrees of a certain secret society, an elderly man in the full ceremonial uniform of that degree came in and looked at me for a long moment. “You know, John,” he said finally, “you must be the first man ever initiated into this degree who wears his hair in a ponytail.”

“Yes,” I said, “and we’d better hope I’m not the last, either.”

He nodded after a moment and went past me into the lodge room, and the ceremony began a few minutes later. The old man’s name was Alvin Gronvold; during the few years I knew him before his death, he was a friend and mentor as well as a lodge brother. To him, and to all the men and women of his generation who kept the secret societies of the western world alive when they were ignored, ridiculed, or condemned by almost everyone else, this book is dedicated.

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

R

S

T

U

V

W

Y

Z

Bibliography

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

Behind the ordinary history of the world, the facts and dates that most of us learn in school and forget immediately thereafter, lies a second, hidden history of secret societies, lost civilizations, sinister conspiracies and mysterious events. This shadow side of history has become a pervasive theme in the popular culture of recent years. In an age of politicians who manipulate facts for their own benefit, scientists who invent data to advance their careers, and scholars who let their prejudices all too obviously shape their judgment, only the foolish – or those with agendas of their own – accept the claims of authority blindly.

Like the Holy Grail of legend, though, the truth behind commonly accepted realities is easier to seek than to find. Since the 1960s, when alternative visions first broke through into the cultural mainstream of the western world, the hidden history of the world has become the storm center of a flurry of uncertainties. What were the real origins of Christianity, the Freemasons, or the French Revolution? Do secret societies actually control the world, and if so, what do they plan to do with it? Does the hidden hand behind history belong to a cartel of bankers, a Gnostic secret society, the Catholic Church, the benevolent masters of the Great White Lodge, alien reptiles from another dimension, or Satan himself? Look at any five books or documentaries on the subject, and you can count on at least six mutually contradictory answers.

Fortunately, there are pathways through the fog. No secret society is completely secret, and even the murkiest events of hidden history leave traces behind. Theories about the shadow side of history have a history of their own. Current ideas about the Bavarian Illuminati or the lost continent of Atlantis, to name only two examples, mean one thing in the hothouse environment of the modern alternative-realities scene, and quite another in context, as ideas that have developed over time and absorbed themes and imagery from many sources. Errors of fact and disinformation can often be traced to their origins, and useful information unearthed from unexpected sources. All this can be done, but so far, too little of it has been done.

The Element Encyclopedia of Secret Societies is an alphabetic guide to this shadow side of history, and it attempts to sort out fact from the fictions, falsifications, and fantasies that have too often surrounded the subject. True believers and diehard skeptics alike may find themselves in unfamiliar territory, for I have not limited myself to the usual sources quoted and challenged in the alternative reality field; the material in this book has been gathered through many years of personal research, using scholarly works as well as more unorthodox sources of information. A bibliography at the end, and the suggestions for further reading following many of the articles, will allow readers who are interested in checking facts to do so.

Another resource I have used, one that will inevitably raise the hackles of some readers, stems from my personal involvement in secret societies and the occult underground of the modern world. I am a 32° Freemason, a Master of the Temple in one branch of the Golden Dawn tradition and an Adeptus Minor in another, the Grand Archdruid of one modern Druid order and a member of three others, and an initiate of more than a dozen other secret societies and esoteric traditions. The world of hidden history has been a central part of my life for more than 30 years. I make no apologies for this fact, and indeed some of the material covered in this book would have been much more difficult to obtain without the access, connections, and friendships that my participation in secret societies has brought me.

Many people have helped me gather information for this volume or provided other assistance invaluable in its creation. Some of them cannot be named here; they know who they are. Among those who can be named are Erik Arneson, Dolores Ashcroft-Nowicki, Philip Carr-Gomm, Peter Cawley, Patrick Claflin, Gordon Cooper, Lon Milo DuQuette, John Gilbert, Carl Hood Jr., Corby Ingold, Earl King Jr., Jay Kinney, Jeff Richardson, Carroll “Poke” Runyon, Todd Spencer, Mark Stavish, Donna Taylor, Terry Taylor, and my wife Sara. My thanks go with all.

Note: Readers will notice the occasional use of a triangle of dots instead of an ordinary period. This is because I have followed the Masonic punctuation practice when abbreviating Masonic terms.

A

ACCEPTED MASON

A member of a lodge of Masons who is not an operative Mason – that is, a working stonemason – but has joined the lodge to take part in its social and initiatory activities. The first accepted Masons documented in lodge records were Anthony Alexander, Lord William Alexander, and Sir Alexander Strachan of Thornton, who became members of the Edinburgh lodge in 1634. Sir Robert Moray, a Hermeticist and founding member of the Royal Society, became a member of the same lodge in 1640; the alchemist and astrologer Elias Ashmole was another early accepted Mason, joining a lodge in England in 1646. They and the thousands who followed them over the next century played a crucial role in the transformation of Freemasonry from a late medieval trade union to the prototypical secret society of modern times. See Ashmole, Elias; Freemasonry; Moray, Robert.

Further reading: Stevenson 1988.

ADONIS, MYSTERIES OF

A system of initiatory rites originally practiced in the Phoenician city of Byblos, in Lebanon, to celebrate the life, death, and resurrection of the old Babylonian vegetation god Tammuz, lover of Ishtar and subject of a quarrel between her and her underworld sister Ereshkigal. Local custom used the Semitic title Adonai, “lord,” for the god; after Alexander the Great’s conquests brought Lebanon into the ambit of Greek culture, the god’s name changed to Adonis, while Aphrodite and Persephone took the places of the older goddesses. In this Hellenized form the mystery cult of Adonis spread through much of the Middle East.

According to Greek and Roman mythographers, Adonis was the son of an incestuous affair between Cinyras, king of Cyprus, and his daughter Myrrha. He was so beautiful that the love goddess Aphrodite fell in love with him, but while hunting on Mount Lebanon he was gored to death by a wild boar. When he descended to Hades, Persephone, the queen of the underworld, fell in love with him as well and refused to yield to Aphrodite’s pleas that he be allowed to return to life. Finally the quarrel went before Zeus, king of the gods, who ruled that Adonis should live six months of the year in the underworld with Persephone and six months above ground with the goddess of love.

Brief references to the mystery rites suggest that initiates carried out a symbolic search for the lost Adonis, mourned his death, and then celebrated joyously when he returned to life. All this follows the standard pattern of Middle Eastern vegetation myth, with the deity of the crops buried with the seed and reborn with the green shoot, only to be cut down again by a sickle the shape of a boar’s tusk. The same pattern occurs in the Egyptian legend of Osiris, the myths behind the Eleusinian Mysteries of ancient Greece, and arguably in the Gospel accounts of the life and death of Jesus of Nazareth as well. See Christian origins; Eleusinian mysteries.

Many scholars during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries recognized the common patterns behind these myths and many others, and argued that worship of the life force expressed through the fertility of vegetation, crops, and human beings was the source of all religion. These ideas found a ready audience in secret societies of various kinds, and similarities between contemporary secret society rituals and surviving information about the mysteries of Adonis encouraged secret society members to draw connections with this and other classical mystery cults. Older works on the origins of Freemasonry commonly list the mysteries of Adonis as one of its possible sources. See fertility religion; Freemasonry, origins of.

ADOPTIVE MASONRY

A system of quasi-Masonic rites for women, Adoptive Masonry appeared in France in the middle of the eighteenth century; the first known Lodge of Adoption was founded in Paris in 1760 by the Comte de Bernouville. Another appeared at Nijmegen, the Netherlands, in 1774, and by 1777 the adoptive Rite had risen to such social heights that the lodge La Candeur in Paris had the Duchess of Bourbon as its Worshipful Mistress, assisted by the Duchess of Chartres and the Princess de Lamballe. Its basic pattern came partly from Freemasonry and partly from earlier non-Masonic secret societies in France that admitted men and women alike. See Freemasonry; Order of the Happy; Order of Woodcutters.

The degrees of Adoptive Masonry take their names from corresponding Masonic degrees, but use an entirely different symbolism and ritual. The first degree, Apprentice, involves the presentation of a white apron and gloves to the new initiate. The second, Companion, draws on the symbolism of the Garden of Eden, and the third, Mistress, on that of the Tower of Babel and the ladder of Jacob. The fourth degree, Perfect Mistress, refers to the liberation of the Jews from bondage in Egypt as an emblem of the liberation of the human soul from bondage to passion, and concludes with a formal banquet. The entire system focuses on moral lessons drawn from Christian scripture, a detail that has not prevented Christian critics from insisting that Adoptive Masonry is yet another front for Masonic devil worship. See Antimasonry.

Despite its ascent to stratospheric social heights, Adoptive Masonry faced an early challenge from the Order of Mopses, a non-Masonic order for men and women founded in Vienna in 1738 after the first papal condemnation of Freemasonry. The chaos of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars finished off the Mopses but left Adoptive Masonry tattered but alive, and it remains active in France at the present. Attempts to launch it in other countries had limited success, although the example of French Adoptive Masonry played a major role in launching the Order of the Eastern Star and similar rites for women in America. See Order of Mopses; Order of the Eastern Star.

AFRICAN-AMERICAN SECRET SOCIETIES

The forced transportation of millions of Africans into slavery in the New World set in motion an important but much-neglected tradition of secret societies. The West African nations from which most slaves came had secret societies of their own, and these provided models that black people in the New World drew on for their own societies. See African secret societies.

The first documented African-American beneficial society was the African Union Society, founded by a group of former slaves in Providence, RI in 1780. The Union provided sickness and funeral benefits to members, raised money for charities in the black community, and networked with similar organizations locally and throughout the country. Like most of the earliest black societies in the New World, it attempted to raise money and hire ships for a return to Africa. Despite the obstacles, projects of this sort managed to repatriate tens of thousands of African-Americans to West Africa, and founded the nation of Liberia.

By the time of the Revolution, though, most American blacks had been born in the New World; their goals centered not on a return to Africa but on bettering themselves and securing legal rights in their new home. The rise of a large population of free African-Americans in the large cities of the east coast inspired new secret societies and beneficial organizations with less direct connections to African tradition. Among the most important of these were Masonic lodges, working the same rites as their white equivalents. From 1784, when African Lodge #459 of Boston received a dispensation from the Grand Lodge of England, Prince Hall lodges – named after the founder of African-American Freemasonry – became a major institution in African-American communities and provided a vital social network for the emergence of the earliest black middle class. By the beginning of the American Civil War Prince Hall lodges existed in every state in the North, and had a foothold in the few Southern states with a significant free black population. See Prince Hall Masonry.

Freemasonry was not the only secret society of the time to find itself with a substantial African-American branch. A social club for free blacks in New York City, the Philomathean Institute, applied to the Independent Order of Odd Fellows (IOOF) in 1843, intending to transform their club into an Odd Fellows lodge. The IOOF rejected their application, and the Institute then contacted the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows in England and received a charter. With its innovative system of sickness and funeral benefits, Odd Fellowship found an immediate welcome among African-Americans, and expanded into the West Indies and black communities in eastern Canada as well. See Odd Fellowship.

While Prince Hall Masons and Grand United Order Odd Fellows were the most popular fraternal societies among African-Americans before the Civil War, many other societies emerged in the black community during that period. Secret societies faced competition from public voluntary organizations rooted in Protestant churches, however the same cultural forces that drove the expansion of secret societies in the white community helped African-American secret societies hold their own and expand, especially in Maryland, Virginia, New York, and Pennsylvania, where more than half the free black people in America lived between 1830 and the Civil War.

The years after the American Civil War saw vast economic and cultural changes across the defeated South, as former slaves tried to exercise their new political and economic rights and conservative whites used every available means to stop them. The Ku Klux Klan used secret society methods to unleash a reign of terror against politically active African-Americans. While the Klan’s power was broken by federal troops in the early 1870s, “Jim Crow” segregation laws passed thereafter imposed a rigid separation between black and white societies south of the Mason–Dixon line. Ironically, this led to the rise of an educated black middle class in the South as black communities were forced to evolve their own businesses, banks, churches, colleges – and secret societies. See Ku Klux Klan.

Masonry and Odd Fellowship were joined by more than a thousand other fraternal societies among Americans of African ancestry. Most of these grew out of the black community itself and drew on African-American cultural themes for their rituals and symbolism, but some borrowed the rituals and names of existing white fraternal orders as an act of protest. The Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks of the World (IBPOEW), for example, came into being in 1898 in Cincinnati, Ohio when two African-American men, B.F. Howard and Arthur J. Riggs, were refused membership in the local Elks lodge because of their race. Riggs obtained a copy of the Elks ritual, discovered that the Elks had never copyrighted it, and proceeded to copyright it himself in the name of a new Elks order. Despite lawsuits from the original Elks order, the IBPOEW spread rapidly through African-American communities and remains active to this day. See Benevolent Protective Order of Elks (BPOE).

During these same years fraternal benefit societies became one of the most popular institutions in American culture, offering a combination of initiation rituals, social functions, and insurance benefits. Americans of African descent took an active role in the growth of the new benefit societies. They had more reason than most to reject the costly and financially unsteady insurance industry of the time, since most insurance companies refused to insure black-owned property. Since nearly all fraternal benefit societies founded by whites refused to admit people of color, blacks founded equivalent societies of their own. See fraternal benefit societies.

Between 1880 and 1910, the “golden age” of African-American secret societies, lodges vied with churches as the center of black social life, and became a major economic force in the black community. One example is the Grand United Order of True Reformers, founded by the Rev. W.W. Browne in 1881 at Richmond, Virginia. In the two decades following its founding, the order grew from 100 members to 70,000, expended more than $2 million in benefits and relief funds, and established a chain of grocery stores and its own savings bank, newspaper, hotel, and retirement home.

The problems that beset most American fraternal benefit societies in the years just before the First World War did not spare the African-American societies; like their white equivalents, few used actuarial data to set a balance between dues and benefits, and aging memberships and declining enrollments became a source of severe problems. The True Reformers were not exempt, and went bankrupt in 1908. The support of the black community kept many others ‘going, until the Great Depression of the 1930s and the mass migration of blacks to northern industrial cities during the Second World War shattered the social basis for their survival and left few functioning. Sociologist Edward Nelson Palmer commented that “[a] trip through the South will show hundreds of tumble-down buildings which once served as meeting places for Negro lodges” (Palmer 1944, p. 211) – a bleak memorial to a proud heritage of mutual aid.

Like its white equivalent, black Freemasonry found a new lease of life in the 1950s, as servicemen returning from the Second World War sought active roles in their communities, but few other African-American secret societies benefited much from this. In the second half of the twentieth century, civil rights organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), radical groups such as the Black Panther Party, and new religious movements such as the Nation of Islam (also known as the Black Muslims) absorbed much of the energy that had driven secret societies a century earlier.

Further reading: Harris 1979, Palmer 1944.

AFRICAN SECRET SOCIETIES

Like other traditional societies around the world, the cultures of sub-Saharan Africa possess a rich and varied body of secret society traditions, many of which still exist today. The sheer diversity of the hundreds of distinct African cultures makes generalizations about African secret societies risky at best, and continuing prejudices and misunderstandings on the part of people in the industrial world cloud the picture further. It is just as inaccurate to think of all African secret societies in terms of masked “witch doctors” and fire-lit dances, as it is to think of all Africans as tribal peoples living in grass huts.

In reality, just as traditional African societies include everything from tribal hunter-gatherer bands to highly refined, literate, urban cultures, African secret societies include initiatory traditions that focus on the education and ritual transformation of children to adults; craft societies governing trades such as black-smithing and hunting; religious and magical societies that teach secret methods of relating to supernatural powers; secret societies of tribal elders or leading citizens that play important roles in the government of many African communities; and many other forms of secret society as well. While most African secret societies are specific to particular cultures or nations, a few, such as the Poro and Sande societies of West Africa, have spread across cultural and national boundaries. See Poro Society; Sande Society.

During the four centuries of European colonialism in Africa, African secret societies faced severe challenges from the cultural disruptions caused by the slave trade and colonial incursions, from the efforts of Christian and Muslim missionaries, and from colonial governments that often identified secret societies as a potential threat to their rule. During this time, African slaves deported to the New World brought several secret societies with them, and they and their descendants created new secret societies of their own, influencing the development of fraternal secret societies in America and elsewhere. Nor did this process of exchange go in only one direction; several secret societies of European origin, including Freemasonry and the Loyal Orange Order, established themselves in the nineteenth century among European-educated Africans and remain active, especially in the large cities of West Africa. See African-American secret societies; Freemasonry; Loyal Orange Order.

Today many traditional African secret societies survive in a more or less complete form, and the twilight of western colonialism enabled some to reclaim the roles they once had in their own cultures. Thus the Mau Mau society, derived from older oath-bound societies in Kenya, played an important role in freeing that country from colonial rule, while the Poro Society in Sierra Leone was able to impose and enforce a “Poro curfew” during the Sierra Leone civil war of the 1990s that protected local communities from the attacks both of rebels and government soldiers. African-descended communities in the New World have also preserved a number of African secret society traditions, and these have become more popular with the decline of Christian control over governments and the spread of religious freedom. See Mau Mau.