Полная версия:

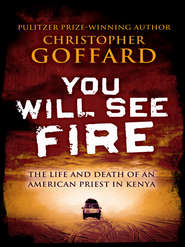

You Will See Fire

You Will See Fire

The Life and Death of an American Priest in Kenya

Christopher Goffard

Dedication

To Jennifer, Julia, Sophia, Olivia,

and my parents

Epigraph

A man who does next to nothing but hear men’s real sins is not likely to be wholly unaware of human evil.

—G. K. Chesterton

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

1 The House at the Edge of the Dark

2 The Lawyer

3 The Collar and the Gun

4 Oaths

5 The Dictator

6 The Clashes

7 The Terrible Place

8 The Raid

9 Lolgorien

10 The Tribunal

11 The Girls

12 We Will All Be Sorted Out

13 The Bureau

14 Manic Depression

15 The Verdict

16 The End of the Time of Moi

17 The Inquest

18 The Labyrinth with No Center

Sources and Notes

Selected Reading

Searchable Terms

Acknowledgments

Other Books by Christopher Goffard

Copyright

About the Publisher

1

THE HOUSE AT THE EDGE OF THE DARK

WHEREVER HE WENT, the man of God carried his shotgun. Like its owner, the double-barrel twelve-gauge was old and broken in places, dusty from miles of hard African road. He kept the splintered stock bound together with a length of black rubber, and he believed it might be his only protection, save for the good Lord and his American name, in a country that had never felt more dangerous.

John Kaiser’s redbrick parish house, without a gate or guard or phone, sat on a twenty-nine-acre plot at the edge of an immense valley rolling away toward the Serengeti Plain. It was the finest house in the township, with five bedrooms and small outdoor water tanks. He would be awake before dawn, lifting his head with difficulty from his narrow metal-frame bed, blinking into the darkness of a room as spartan as a cell. Shapes congealed around him: the crucifix on the wall, the cluttered desk, the shotgun.

He’d be walking the grounds before sunrise, clutching his rosary beads and praying in the dark, his arthritic neck already encased in a thick orthopedic brace. At first light, the rutted murram road running past the parish house acquired a pinkish hue. As the countryside awoke, birdsong filled the surrounding trees, and from the long, wet grass, insects thrummed at his passing heels.

A few yards from his front door stood the church he had built soon after his arrival, five years back, in this tiny township in the heart of Masailand. It was a rough and functional structure, like dozens he’d thrown up across the countryside: corrugated-iron roof, concrete floor, unburnished wood pews, and exposed crossbeams in the vault overhead. He had developed a reputation as a ferocious and tireless builder during his years in Africa; this alone made him an unusual figure among white missionaries. He’d gone up ladders with pockets stuffed with bricks and pulled long roof beams after him by rope. But scattered around the compound now were crude brick structures—the shells of a girls’ dormitory and schoolhouse and dispensary—that he had not mustered the energy to finish in these last pain-racked years. He had begun to doubt he would.

The year was 2000. It was late summer. From his radio came the Voice of America, the cadences of home, where the news of late had been dominated by the presidential race to succeed Bill Clinton. He would sit down to breakfast in a dining room with lime green walls, adjoining a living room with a plain worn couch. His diet was as spartan as his room, and his breakfast, laid out by his housekeeper, Maria, would be quick and simple—some mandazi, a fried sweetbread, and ugali, the maize porridge that was the country’s staple.

By midmorning, he would be steering his Toyota pickup over the gravel driveway onto the red-dirt ribbon that formed Lolgorien’s one main road. As in many of Kenya’s disease-blighted towns, there were only a few intact families. Flanking the main road on either side, for a few blocks at the center of town, were tumbledown clusters of one-story shops topped by rusty roofs of corrugated iron, dukas, wood-plank stands, dirt-floor hotels. Milling there were police, game wardens from the Masai Mara, government functionaries, and the pack of prostitutes that served them. Shoulder-to-shoulder on the porches lounged gaunt, long-limbed Masai men, sinewy, sandaled, with shaven scalps, the ropy skin of their stretched and punctured earlobes bright with beads, their bodies wrapped in crimson and vermilion shukas. Their staffs were slanted across their laps or angled over their shoulders; a Masai male who didn’t carry one was considered a worthless guardian against the lions, and the tradition persisted even as the lions had begun to vanish. They were nomadic cattle herders who lived in manyattas—circular arrangements of loaf-shaped mud-and-dung huts, where they corralled their cattle at night, secure from predators behind lashed-together fences of thorned acacia branches. Cows supplied their diet: milk mixed with blood collected from a small arrow puncture in the animal’s neck. White missionaries sometimes talked of feeling like strangers among Africans, even after decades of taking their confessions and serving them Mass and burying their dead. No group elicited this sense of exclusion as powerfully as the Masai. During the priest’s years in Masailand, conversions had been slow, nothing like the success he’d had for decades among the Kisii. The priest knew he was a peculiarity to them, maybe the strangest mzungu they had known—an American, rich by definition, who insisted on a life of hard physical labor in the sun and had chosen to live without a woman or children. Inexplicable enough was a lifetime without physical love—only witch doctors live alone, people said—but a man who consciously forsook progeny meant an even deeper strangeness.

From his truck, as he rumbled through town with the shotgun and rosary beads resting beside him, he could see the Masai watching him from the porches, their gaze indifferent and unreadable in the baking sun. He had to assume that some of them were monitoring his movements, informing on him, reporting back to the man some called “the Butcher,” Julius Sunkuli. Many—it was impossible to know how many—were linked to Sunkuli by family or clan or ties of financial loyalty or fear.

This was Sunkuli country. He held the local parliamentary seat. He was not just the area’s political kingpin and its most prominent Masai but also one of the most powerful figures in the country. He had grown up on the grass plains, tending his family’s goat herds. He had been an altar boy and a Christian youth leader, and remained a conspicuous member and benefactor of the Catholic Church. He had been plucked from the margins of power by His Excellency the President of Kenya, Daniel arap Moi, East Africa’s longest-reigning gangster-statesman, who had given him a place in his inner circle. As minister of state in charge of internal security, Sunkuli commanded a vast police network, and was widely rumored as a possible successor to the president. When he smiled, the gap in his lower jaw showed where his teeth had been chiseled out, evidence of his childhood initiation as a Masai warrior. Sunkuli was different from some of Moi’s other top men, with their charm and European degrees. Sunkuli emitted a raw street fighter’s intelligence, a backcountry roughness that had persisted through his years as a lawyer, magistrate, and political boss.

To Kaiser, Sunkuli seemed the crystallized embodiment of Moiism, the perfect product of a culture of Big Man impunity—widely feared, apparently untouchable by the law or the electorate. For years, the priest had received reports that Sunkuli had been preying on schoolgirls; some said the countryside was dotted with his unacknowledged children. Kaiser had helped push a legal case, now working its way through the courts, in which a young Masai girl from his parish had accused Sunkuli of rape; it had made headlines. The priest described him as his “biggest worry.” It will be one or the other of us, he told people. There was no way to know how many spies he might have. Some people said that one of them was living in the priest’s own house.

Kaiser would pass on, into the countryside. His truck had a whimsical name, “the Helicopter,” because it frequently left the roads, heaving and lurching over terrain that brought anguish to his neck. Throughout the day, he would venture deep into the grasslands, through drenching rains and sucking mud and hard sunlight, to reach the scattered outstations of his vast parish. He had traversed this mapless landscape so many times that the topography itself supplied his signposts: a fig tree, a ridge of rock, a gulley. Certain arcane knowledge accrued to a man over a lifetime in the bush. He had learned to start his truck with a coin when he lost the key, and he understood the utility of a bar of brown soap to patch cracks in a leaking gasket. He had learned to deflate the tires to surmount a bad hill, and to sit on a crate when the front seat fell apart.

A fiercely doctrinaire Catholic who espoused obedience to the letter of Vatican law, he was nevertheless adept at bush-missionary improvisation. He found that a Coke bottle was a serviceable receptacle for holy water. When he’d traveled hours, only to discover he had forgotten the Communion wafers, he looked for the nearest kiosk that sold chapati—a doughy flat bread resembling a pancake—to transform into the Savior’s body. A crack shot, he’d been vanishing for years into the elephant grass with his shotgun, stalking wildebeests and impalas, warthogs and zebras and buffalo. He would skin the carcasses—sometimes yanking the skin free with ropes attached to his truck—and carve up the meat and distribute it among the parish schools. He whittled the stocks of his guns and made his own bullets, shaving lead from an old battery and pounding the pieces into slugs. He shook in half rounds to conserve gunpowder and to mute the noise when he hunted, in case a game warden was within ear-shot. Poaching had been outlawed since the late 1970s, but that was one of man’s laws and therefore negotiable.

Some regarded him as an unbreakable man, the “John Wayne of priests.” They saw the six-foot-two former U.S. Army paratrooper who could creep close enough to a buffalo to kill it with a single half-powder round through the lungs or heart (to take a second shot gave wardens a bead on your location). They saw the hunter who refused to leave a wounded animal behind, despite the danger of pursuing an enraged, bleeding beast into the bush. He had promoted a fierce image, in part, as a form of protection. Even before he was an enemy of the state, he recognized the shotgun’s value in deterring ordinary trouble. He hauled it outside now and then to shoot at birds; everyone knew the American priest was armed. He had performed prodigious physical feats well into middle age, hunting, hauling, digging, building. When he arrived in Masailand in his early sixties, he was still strong and fast enough to kill a rabbit with a hurled stone or a dik-dik with an ax, and he’d be on top of the animal before it even fell, hacking with a big overhand arc. He was still popping wheelies on his motorbike for the amusement of the Masai girls.

He’d come through the crucibles of any bush missionary—hepatitis, typhoid, malaria, amoebic dysentery. He’d broken bones in motorcycle spills and survived a roof beam crashing on his neck during a construction project.

But the last few years had been brutal even by his standards; his body had become a catalog of anguish. Though he hated seeing the doctor, he’d gone dozens of times. He’d endured prostate cancer, and multiple bouts of malaria that grew increasingly resistant to quinine and left him helpless, sweating through fevers and convulsions and hiding from harsh sunlight and the gouging of birdsong in the ears, the terrible cold seizing him, his body without bones or muscles or volition for weeks. At times, as the decades accreted in the bones, a man could feel like the sum of all the stumbles off his motorcycle and falls in the mud, a creature of collapsing cartilage and inflamed joints and ulcers. He was a former soldier, and a soldier did not complain, but on his best day now he couldn’t move his neck without pain. He wore the cervical collar everywhere, except at Mass. There, facing his faithful, he refused any concession to his decaying sixty-seven-year-old body. His parishioners streamed down from the hills in their bright tribal wrappings to hear him speak in Swahili of the risen Savior, to stand in line at Mass as the enormous old white hands, aching now like the rest of him, leaking strength every day, cradled God Himself aloft.

Everybody in the area knew the American priest, and many depended on him for food and school fees; they would surround him as soon as he pulled up to a cluster of huts or to the little brick schools or churches. By the side of the road, in the shade of eucalyptus trees, he bowed his head and listened to their confessions. I have stolen a cow, Father. I have slept with girls, Father. I have struck my wife, Father. So much of his knowledge about the country had arrived in this fashion; the chronicle of sins formed an infinitely more accurate barometer of the country’s soul than did the Nairobi newspapers.

With luck, he would be home before nightfall. The road bristled with bandits, or shifta, and the sun didn’t linger on the horizon. It was nothing like the protracted twilights of his Minnesota childhood—that long dream hour of crying cicadas and droning mosquitoes. Here near the equator, night scythed down as swiftly as a panga knife; one writer compared the experience to having a sack pulled over your head.

The shotgun would stay with him as he walked the grounds at night, locking the church, shuttering the windows of his home, double-checking the locks; it stayed with him as he walked down the long, shadowed hallway to his room, the last on the left. Scattered before him at his desk, dimly illuminated by generator light, were dangerous documents. They told the story of the secret history of his adopted country, a subterranean narrative of land and blood. They chronicled the sins of Kenya’s rulers—decades of land-stealing, ethnic carnage, rape. There were affidavits from peasant farmers, land deeds, newspaper clips, correspondence, accounts from local girls. He had been collecting them for years. He spent hours in his room, reading, poring over documents, making notes in his journal. For some time, he’d been anticipating his violent death, warning friends and family in the States to expect it.

For most of his career as a bush missionary, save for the church and the tribes he had lived among, few in Kenya had known his name. He had done a fair job of impersonating the other good, hardworking, politically impassive men of Christ. He had raised little noise outside the Church, with the rationalization that he had plenty of God’s work to keep him busy. Then, no longer young or even middle-aged, he’d become chaplain at a hillside displacement camp called Maela, where he witnessed a scale of misery that nothing had prepared him for—ubiquitous choking dust, mud, disease, burned skin sloughing off children’s hands like gloves, and then the government’s nighttime raid on the camp. Good Lord, some of the refugees had even been singing as they were crammed onto trucks to be scattered across the countryside, singing because they’d actually believed the president’s promise that he would find them land. That six-month experience—culminating in his own beating and banishment from the camp—had forced him to reexamine his silence. Some of the lightness went out of him; photos showed a depth of sadness shadowing his eyes after that.

It would have been possible, even then, for him to melt back into his missionary work. His bishop, whose mantra was “Don’t provoke,” had sent him to the house in Masailand at the country’s southwest edge—about as far as he could go without spilling into Tanzania—with the hope that the remoteness would keep him out of trouble. The bishop had been mistaken. It had not deterred Kaiser from appearing at the Akiwumi Commission—a tribunal launched by President Moi, with the ostensible goal of probing the causes of the tribal clashes that had killed more than one thousand people in recent years. The real purpose, many suspected from the start, was to conceal the government’s central role in the carnage. Kaiser had been warned against speaking. His bishop believed the tribunal a waste of time, and Kaiser’s intention to name names a pointless provocation.

Some African churchmen considered it an embarrassment that a white man should presume to lecture them about their affairs. The missionary’s role in Kenyan history had been a fraught one. Determined to bring pagans of the Dark Continent into the Christian fold, the early missionaries preached not just salvation but also the superiority of white civilization. Many of Africa’s independence leaders, including Kenya’s, had been products of missionary educations. But it was easy for Africans to view the missionary legions with ambivalence, if not outright hostility. They had built schools but taught Africans to hate themselves. The Church had been a spearpoint of the colonial land grab, legitimizing the conquest, and had sided with the British against the Mau Mau uprising of the 1950s, defining the struggle as one of light versus darkness, God versus Satan. Jomo Kenyatta, Kenya’s first president, had put it this way: “When the missionaries arrived, the Africans had the land and the missionaries had the Bible. They taught us to pray with our eyes closed. When we opened them, they had the land and we had the Bible.” Kaiser had inherited this uneasy legacy. For many of his colleagues, guilt fostered paralysis and passivity—a feeling that African politics was best left to Africans, lest the Church be accused of reproducing its past sins.

Yet Kaiser had gone to the tribunal, braving the bad roads, waiting in the makeshift courtroom in his ironed clerical blacks, with his neck brace and his Roman collar and a folder of documents. Up he walked, a broad-shouldered, long-limbed man with a loose, slightly bandy-legged gait and thinning white hair. He was not a churchman of rank, not a bishop or a nuncio, not even the priest of a politically important parish like Nairobi. He was, up until then, a man of small importance to history—just a bullheaded old mazungu from one of the country’s poorer corners.

His voice was high and thin, almost feminine, incongruous with his cowboy gait, but it had not betrayed him that day. He had named names—a roster of the regime’s untouchable potentates. Sunkuli was prominent among them. This was dangerous enough, but then he went on to do the unpardonable: He named Moi himself. People would remember his voice as steady and even and insistent. Listening to it, it had been impossible to tell that he’d been sleeping with his shotgun for weeks, afraid that he would never be allowed to speak, afraid that once he began, he’d never be allowed to finish. He testified for two days, sparring with government lawyers, trying to distill the dark knowledge he had absorbed. Long portions of his testimony ran verbatim in Kenya’s daily newspapers, and in an instant the backwoods missionary had become a symbol of national conscience, a source of hope, a galvanizing force.

That was how it began: not just the fame but also the steady note of dread in his letters, the unbanishable sense that he would be called on to die violently in this green, malarial patch of East Africa. In the eighteen months since then, he had been upping the stakes, demanding not just that Moi be prosecuted at the Hague, where he vowed to serve as a witness, but pressing for criminal charges against Sunkuli, as well. The good, gentle men of his missionary order found it exasperating, his unwillingness to listen to reason, to moderate his tone, to demonstrate a normal man’s respect for death. You’re going to get us killed, John.

AGAINST HIS WINDOW pressed the cold deep-country dark, and from it rose the distant bedlam of hyena packs on the savanna. Cackles, whoops, rattles, gibbers—in the right state of mind, these sounds could be calming, melodic. Africa’s nightsounds used to be music to him, and there were nights as a young missionary in the open Mara that he would recount as if he were the world’s luckiest man. Picture him: the stars ablaze above, the breeze rippling quietly through the dry waist-high grass, the winged ants battering his lantern, the carcass of a wildebeest or zebra gutted in his truck and the aftertaste of its fried heart in his mouth, and all around the cacophony of animals in their night rituals. He had lived close to nature’s beauty and cruelty since childhood. It had suited him, this life. Now, the veldt noises lashing against his room’s little square of light seemed to remind him of the closeness of his own death. Again and again, the priest told people, That is what they will do to me if they catch me. Leave me as carrion. Human flesh was familiar to the scavengers, for the Masai still were known to leave their dead unburied, smeared with animal fat to hasten the bodies’ disappearance. Nothing lasted long out there, among the immense spear-beaked marabou storks—bald, Boschian grotesques whose wrinkled heads seemed born in some stygian pit of blood and ash—and the hyenas, spotted, hulk-shouldered, level-eyed. These he seemed to fear most. They fed deep on the entrails of living, thrashing gazelles. They ate the viscera and the muscles and the skin, crunched through bone and swallowed the hair, whole corporeal forms vanishing in the space of hours. They were, to assassins, an ideal evidence-disposal system. Everyone knew the story of the young English traveler Julie Ward, who had been murdered not far from here, her body devoured by animals, and the truth about her death—like so many crimes in Kenya—gone with equal thoroughness.

As a paratrooper, he’d been taught that darkness can be a friend and ally; a trained man can turn it to his advantage. Here, however, the mind peopled that void with innumerable evils; he knew the advantage was theirs, not his. Every odd sound, every rustle and crunch, seized his attention, his body tensing. He knew they could be out there even now, crouched, smoking, silent, patient, catching a glimpse now and then of his tall silhouette passing by a window, waiting for him to be separated from his gun, for his vigilance to slip. They’ll say I killed myself. Don’t believe it. He clutched his rosary beads. He prayed for strength.

THROUGH THE SUMMER, his missionary bosses and fellow priests made the trip from Nairobi to plead with him: Go back to Minnesota, John. Rest.

They knew there was small chance of reasoning with a man of such preternatural stubbornness. If he went home now, he explained, Kenya’s rulers would probably never allow him to return.

Any of his superiors could have ordered him out of Lolgorien, back to the States. He had taken a vow of obedience, and he very well might have complied; his last years would have been spent peacefully among his boyhood haunts in Otter Tail County, Minnesota, fishing quietly among the mayflies, visiting old friends and family, and browsing the cemetery slabs for childhood names. But his bosses gave no orders. Their preferred method was to offer suggestions, appeals to reason, pleas for prudence. These, he could ignore.

The summer was a dry one in Lolgorien, the green leaching from the hills until the grass was brown and short and brittle. His water tanks were depleted, and across the hills the skin tightened on the ribs of the cattle. The Masai watched the sky constantly, knowing that if it remained empty, their calves would begin to die first. Cows were not just their livelihood but God’s special bequest to their tribe. Every few seasons, droughts stole them in large numbers, and it was a terrible thing to hear the weeping of a proud Masai. They prayed and made sacrifices, and still nothing brought the rain.