скачать книгу бесплатно

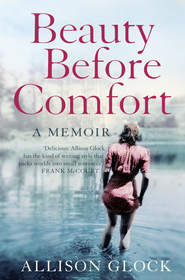

“Beauty before comfort,” she would say as she trimmed her brows and cinched her belts corset-tight. My grandmother is so beautiful that she has never once been comfortable, a cross she bears with the subtlety of Liberace. Even now, at the age of eighty-one, she has her hair colored weekly and doesn’t descend the stairs without full makeup. If an opera spontaneously broke out at her nursing home, Grandmother would be appropriately dressed.

It is a legacy she has passed down to her own daughters, and they to theirs. Generations of women painting themselves to perfection, ramming their feet into tiny shoes, sucking in their bellies, dousing their hair with enough spray to gag a horse, girl after girl learning the value of being “as pretty as you can be.”

As family legacies go, beauty before comfort is a particularly cumbersome inheritance. For my mother, it necessitates a minimum full hour of prep time every morning, time that lengthens as she grows older. For my youngest sister, it requires an arsenal of beauty products—enough to fill a second suitcase when she travels. For me, it meant coming to terms with the fact that in a long line of great beauties, I was not a great beauty, and that I’d better start honing my sense of humor.

For all of us, it means living with a low-grade anxiety, a murmur in our brains fueled by our collective self-consciousness and our compulsive sizing up of our place in any room—Who’s prettier? Who am I prettier than?—as if our very survival depends on our ability to seduce.

For Grandmother, the pursuit of beauty meant something deeper. Born as she was in a factory town, tiny and blinkered and perched precariously on the banks of the Ohio River, beauty meant nothing less than freedom. Ugly girls didn’t escape to Hollywood and sit by the pool in leather mules. Ugly girls didn’t marry up and fly away on airplanes. Ugly girls got left behind and never knew any better.

Grandmother believed that there are people who tell stories and people who inspire the telling, and she intended to be the latter. “A pig’s ass is pork,” she would say when the local men pecked after her, wanting to know her heart’s intentions. Or maybe, “It ain’t lying if it’s true.” When the boys would confess their desires, daisies in trembling hand, Grandmother would smile and weave the flowers into a halo for her hair. Before it was all over, she would have seven marriage proposals and a body like Miss America and her share of the tragedies that befall small-town girls with bushels of suitors and bodies like Miss America, girls who dare to see past the dusty perimeters of their lives.

She keeps a memory book from this time, her youth, before she was tired and widowed and old, when she was cream-fresh and believed her life was as open as the road. All women kept scrapbooks back then, hoping somehow that their history would mean more than most. My grandmother’s is a three-ring brown plastic binder with black construction-paper pages holed out at the edges and snapped inside. The pages have worn through the years and many have Scotch tape bonded to the seams. In the book are newspaper clippings and birth announcements, ticket stubs and good-natured platitudes cribbed from local papers, bromides along the lines of “Though you have but little or a lot to give, all that God considers is how you live.” (I can only figure she found these snippets ironic, as my grandmother has never shown the least bit of interest in God or any of his considerations.)

For the most part, there are photographs. Black-and-white images of her and her boyfriends, sitting on cars, standing on fences, the men smoking cigarettes in World War II uniforms, Grandmother fanning out her dresses to best advantage. On many of the shots of the men, there are love notes penned in the corners, hungry scrawlings declaring their affection for the girl behind the camera.

There must be more than one hundred of these pictures, I know because Grandmother and I have often looked at them. Every Christmas or Fourth of July, out comes the memory book and the stories.

“Now, that boy sent me a big bottle of Chanel Number Five from boot camp, I saved the bottle. And that boy took me to the Kentucky Derby; I had a mint julep. And that boy raised greenhouse roses. And that boy took me roller-skating. And that boy died in the war.”

She tells me which boys she loved and which loved her. She tells me about her brothers and her sister and her mother and father. She tells me about her house and what went on there and how it was to be young in West Virginia, to be a skinny, eager child with disobedient hair and bottomless longing. Certain pictures are like songs, making her cry no matter how many times she sees them. Almost every snapshot is labeled neatly with the subject’s name—including each photograph of my grandmother: “Aneita Jean Blair” tightly jotted in the white border at the top, a nod to the future she dreamed she’d have, one where strangers knowing who she was would matter.

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_d1e4983f-4a42-5684-99aa-47076756e2f5)

The state of West Virginia was born in conflict and has retained lo these many years a mulish attitude problem. The people born there are chippy. It’s a birthright.

The state came to be in an act of war, when the western half of the state broke off from its eastern parent, Virginia, in 1863. The two sides disliked each other with familial intensity. The western half envied the wealthy eastern half. The eastern half was ashamed of the western half. The westerners saw the easterners as idle slave owners. The easterners saw the westerners as boorish rednecks.

“What real share insofar as the mind is concerned could the peasantry of the west be supposed to take in the affairs of the state?” said easterner senator Benjamin Watkins Leigh on the floor of the 1829 Virginia legislature.

“Screw you,” said the peasantry of the west.

Western Virginians were sick of the ridicule, of being overlooked when it came to building schools, of being dismissed as “woolcaps” by the richies who lived in the pampered south of the state. Then, around 1850, the state of Virginia borrowed $50 million for improvements and the construction of roads, canals, and railways. The only money spent in what would become West Virginia was $25,000to build the “Lunatic Asylum West of the Allegheny.”

It was not a promising precedent, and the two regions formally went at each other’s throats. The rivalry played out in the legislature for years, until finally President Lincoln stepped in and pressured Congress to push Western Virginia’s independence through. This decision “turns so much slave soil to free,” he said. It was “a certain and irrevocable encroachment upon the cause of the rebellion.”

Thus was born a state and the lasting tradition among its people of giving whomever they please the finger. “Mountaineers are always free,” declares the state motto. This history was not lost on my grandmother.

Aneita Jean Blair was born at the foot of her mother’s bed on September 30, 1920.

“I was born ugly,” my grandmother says. This is a lie, but it is a lie she believes.

In the album, there is only one photograph of the infant Aneita Jean. It was taken on the Fourth of July and she is roosting on her father’s knee, a lump in white cotton, with a black wick of hair falling down her forehead. Beside her, her two-year-old brother, Petey Dink, rests an American flag on his shoulder, his free arm raised to shield his eyes from the sun. A horse and buggy is parked behind them. It is impossible to tell if she was in fact ugly, but, given the gene pool, it seems unlikely.

On the day my grandmother entered the world, it was storming, and because her mother always kept the windows open, Aneita Jean Blair was not only ugly but in the rain. When her father rushed into the bedroom, Grandmother was already there, pinned down by her mother’s foot, wailing and kicking in a runnel of wet. It is because of this that she says she is crazy.

“I’m crazy, you know,” she’ll tell you soon after you meet her. She is indiscreet. She tells the grocery clerk she’s crazy, the bank teller, the librarian. She once met a boyfriend of mine, grabbed his arm, told him she was crazy, then suggested the two of them climb into a dog crate and “see what happens.”

Aneita Jean weighed seven pounds at birth, a weight she would more or less carry until the first grade. She was a colicky baby, a crier. She spent the first years of her life in a foul mood, believing even then that a life without beauty is a pile of slop.

In a photo of her as a toddler, Aneita Jean is standing outside, her mouth screwed into a knot of agony, her hair sticking up like a pitched tent. When she was two, her older brother, Petey, had given her a doll that frowned, which made everyone laugh, but which she despised and pinched when no one was looking.

“Everybody thought it was funny,” she says. “I didn’t think it was so damn funny.” And then: “Buster Keaton never smiled, either, and everybody was mad for him. Ah, horseshit feathers.”

In public, Aneita Jean would stand eyes forward, lips flattened, hair chopped close to her neck, reeking of defiance and looking lifetimes older than the little girls next to her, with their eager smiles and shy eyes. Family lore has it that it would be a full three years before she ever smiled. Three years, never so much as revealing a tooth.

I’m going to leave here one day,” she’d say to her mother years later, her head nestled in her lap.

“Why would you go and do a thing like that?”

“Because.”

It wasn’t much of an answer, but then, as a little girl, she hadn’t really thought it out. It was an instinct. She was going to leave, become a painter or a singer; she was going to wear dresses with sequins and make art and meet dark men in suits who smoked pipes and nodded their heads in approval.

“No one leaves here, Jeannie,” her mother, Edna, would chide, tucking a curl of hair behind her daughter’s ear. Edna herself had moved only twice, arriving at the new spot within a few hours of the last.

That few people escaped West Virginia was true, but an irrelevancy to Aneita Jean. Ugly or not, she decided that by the time she was sixteen, she’d find a man who would carry her over the mountains to a place where all the women lolled about, resplendent in chiffon and diamonds, and all the men looked like Errol Flynn before he started drinking so much. Someplace glamorous. Like Pittsburgh.

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_a3a18ece-756e-5345-bf1c-72c7b1dc4807)

“I couldn’t stand the dirt. The alleys. The ignorance. You know how you drive through towns and wonder, Why would anyone live here? That’s how I felt. But we lived there. We lived there our whole dingdong lives.”

Aneita Jean Blair was the second child born to Edna Virginia McHenry Blair and Andrew Charles Blair. Edna was a natural flirt. She was Irish, bosomy, and spirited, with jowly cheeks that vibrated when she laughed. Andrew, a Scotsman, was not a jovial person and seemed in a constant state of mystification as to how he’d ended up married to one.

The year my grandmother was born, West Virginia was in the throes of a moonshining epidemic. Every month, more forbidden stills were discovered, and in a raid just weeks before Aneita Jean’s birth, state officials found a still in a nearby church, news that sent Edna into hysterical laughter. Andrew didn’t cotton to irony, so a month later, when the Ceramic Theater showed The Family Honor, “a picture that sharply contrasts right thinking and right living with false pride and evil deeds,” Andrew Blair made sure his wife saw the show.

Andrew and Edna would have five kids altogether, all spaced roughly two years apart. The first was Andrew junior, whom everyone called Petey Dink, then Aneita Jean, then Forbes, followed by Alan, and, finally, Nancy. The Blairs were an attractive family, but Petey Dink and Aneita Jean were dealt the best genetic hand. Both were tall and lean, with wide eyes that jumped off their pale round faces. Both had small plump mouths, and with their translucent skin and golden red hair, they looked every inch like their Celtic forebears.

Forbes was a blonder, blander version of Petey, more like his father, sturdy and tense, while Alan and Nancy were born with brown curls and longer faces. They looked like mournful cherubs, and they studied intently while Petey and Aneita Jean robbed apple orchards, their laughter trailing behind them like a kite.

They all lived in a brown brick and clapboard Victorian at the corner of 917 Phoenix Avenue, in Chester, West Virginia, just on the cusp of the good neighborhood, where the people didn’t have to stretch sugar or send their kids to the government depot for cans. Just a few blocks away, they could wade into the woods and play amid the dogwoods, rhododendron, wild violets, and long, wispy trees that rustled like bamboo.

Their town was known for two things—pottery factories and not being as pitiable as its downriver neighbor, Newell.

Pity being a relative thing in West Virginia, the distinction boiled down to small details. Newellies still kept chickens in their yards. In Chester, there were fewer chickens and more flower beds, and on occasion, in the nicer homes, wallpaper.

The Blairs had flower beds and hand-sewn curtains cut from heavy cotton bark cloth printed with tropical leaves. They had a porch and a walled yard and a stairwell up the center of the house. There were four bedrooms and one bath. The street out front was gray brick, and in either direction there was a view of the factory smokestacks.

Like Newell, Chester was a blip on the east bank of the Ohio River, part of a cluster of small towns that make up the panhandle, Hancock County, a region of steel and brick, but mostly clay. The clay was unique. Plentiful and unusually malleable, it was perfect for making crocks, jugs, stoneware, and china.

Potters lived there, whole generations of them, growing up in cramped company houses, knowing only the job they were trained to do and the folks around them. Starting as early as 1830, people moved to what is now Hancock County, discovered the clay, became potters, and stayed. It was a marriage of resource and craftsman, and it was a marriage for life. “The second-oldest profession,” they called it.

The clay along the Ohio River had a blue tint and smelled of standing water. Once in your nose, the scent never left, just dug deeper into your pores, so each breath reminded you where you were. It was persistent in other ways, digging into fabrics and under fingernails, like white blood, thick and seeping, growing crusty when it dried. Most potters didn’t even bother trying to eradicate the clay; there was always more carried in their pant cuffs, in their hair, on their toothbrushes. Andrew Blair was a potter. And when his sons grew old enough, they, too, served their time in the factories, until the war called them away to more epic fates.

Throughout Aneita Jean’s life, the Blair family was well known in the valley. The family’s combined good looks and social acumen made them easy to spot. Forbes was an usher at the theater. Petey Dink danced with all the ladies, and danced so well that even the wives among them never refused. The whole family, save Edna, was dapper, but even she transcended her plain frocks aided by her round biscuit cheeks and knowing black eyes. Her husband favored layers of starch, stiff shirts and vests and jackets, so crisp and pointy, he looked to be cut out of cardboard.

In one family picture, Petey, fifteen, wears a floral-print necktie with a rumpled dress shirt and high-waisted pants. Aneita Jean, thirteen, wears a pleated skirt and wide-collared shirt. Forbie, eleven, aping his father, looks strangely adult in a herringbone suit, while Alan, nine, and Nancy, seven, sport fitted sweaters and stovepipe pants. Together, they seem to sing from the page, the clothes incidental trappings rustling around their collective confidence; except Alan.

Alan Blair had the misfortune of being born agreeable in a family of severe stoics and manic charmers. He was neither the oldest boy nor the youngest child. He was not the handsomest or the smartest or the cruelest. He was not a jock, a scholar, or a delinquent. He was just good old Alan Mead, shy and curly-headed, and he kept low to the ground and quiet. (Later, he would become an elementary school science teacher who rarely mentioned how he had piloted a drone plane through the mushroom cloud of the first dummy atomic bomb test, or how, as a full commander in the war, he had nearly died in a hurricane off the coast of Japan when his plane pitched into the ocean like a javelin.)

His older brother Forbes Wesley was quiet, too. But his reticence was a manifestation of control and a touch of snobbery. His father, whom he closely resembled, told him that he was better than everybody else, and Forbie believed it. His haughty air won him few friends in the valley. He didn’t mind. Such was the cost of superiority. In the future, his truculence would make him a significant force in the Republican party, friends with the likes of Hoover and Reagan.

Nancy, the youngest, was a change-of-life baby, born when Edna was in her forties. Aneita Jean thought Nancy’s was the most beautiful face she’d ever seen. It was perfect, with skin as lively as water and hair darker than molasses, and she spent a lot of time pretending Nancy was her baby.

Petey Dink, the eldest child, was the most magnetic of all. Lean and beautiful as a greyhound, he was quick-witted and full of beans. He wasn’t much for schoolwork, believing himself smart enough already. He preferred stealing—candy, comics, cigarettes. His teachers tried reprimanding him, but they found it impossible against the tide of his charm.

“I’m sure I could concentrate better if I wasn’t so distracted,” he’d say with a lewd grin when they confronted him about his failing grades.

An instinctive athlete, Pete mastered football and baseball, then quit sports, finding them less stimulating than the company of women, up to and including his sister, Aneita Jean, a girl he adored, even if she was a little loopy.

“He thought I was nuts,” says Grandmother. “But he loved me to bits.”

The Blair family resembled the others in Hancock County only in that they were large, Scottish, and struggling. “We were never going to be wealthy,” says Grandmother. “But my father wanted us to have class.”

And so Andrew dressed his children like adults, and stressed the value of self-improvement. He made rules forbidding most childhood games like tag and hide-and-seek. And he made rules for conduct. Manners were of the utmost importance, as was grammar. At the Blair house, you stood up straight or were poked in the spine with a stiff finger. If your jaw fell open when you read, it was soon smacked shut from the chin.

“Quit your crying,” Andrew would say whenever his children washed up on his knee with troubles. “There’s a price for being special. You want to be like everybody else?”

“He had a hard life,” Grandmother says in a level voice. “His mother was run over by a train.”

The Blair house sat on a corner lot, right at the Harker pottery trolley stop. Because of this, it was a social hub. As potters waited on the front porch for the trolley, Edna would feed them rich slabs of homemade chocolate cake, fan herself with her napkin, and chortle at the stories they shared about the pottery. She liked hearing about life beyond Phoenix Avenue, what men got up to behind closed doors. She could imagine them there, slapping one another on the back, hauling ware, biting into their apples around that big wooden plank they used as a lunch table. She hadn’t been to the factory herself. Andrew wouldn’t allow her to visit, so she rarely went farther than the porch.

“He wasn’t jealous,” my grandmother explains. “He just thought it looked bad. He found my mother disgraceful because of her weight. He used to take her picture off the mantel and slam it on the floor.”

Still, Edna didn’t want for attention. She had the potters, who never tired of her cake or her company, and who shook with laughter when, indecent or not, she matched them joke for joke. Edna tittered most of all. Aneita Jean would sit at her feet, watching her face crack, anxiously mimicking the pitch of her mother’s laughter.

There are just a few photos of Edna in the memory book. In one, she is old as old gets, standing outside next to a neighbor, smiling in her apron, her hair pinned back in a tousled bun. In another, she is young, sitting beside a window in a ladder-back chair, her hands clasped behind her head in reverie. She is gazing off to the left, her face heavy, her eyes shaded with sadness. She wears a linen dress with lace draped along the collar and sleeves. Her hair is in the same loose bun.

Edna Blair mesmerized her elder daughter. Aneita Jean was in awe of her mother’s size, the way her breasts rose like sacks of flour under her apron, how her rump jutted out like a shelf. She often stared at her mother’s fleshy arms, which shook like hung laundry and were badly seared from the too-small oven. Big as Edna was, the men cared little. “Most men didn’t want any bag of bones back then,” says Grandmother. Besides, Edna had ripe skin and a bow mouth and the endearing idiosyncrasy of not knowing how sexy both were. And so when the men laughed, it was because she was funny, but also because in their hearts they imagined for that moment what it might be like to be wrapped inside those giant arms, buried into the soft folds of her chest.

Sometimes, on her way into the house, Edna would turn suddenly and make a garish face, her eyes yanked down to her cheeks, her lips bulged from underneath by her tongue. This would send the potters roaring. Aneita Jean watched her mother and learned without trying how easy it was to please a man. Food and laughter and willing eyes. Everything else blanched to nothingness with time. At least that is what she believed then, as a child cushioned in the shadow of her mother, cake crumbs on her chin, the sweet of it still packed in her teeth.

Aneita Jean knew of no other mothers who made faces. Nor any who made men laugh. The other mothers she knew were sour and tired and barely smiled at all. Sometimes, these women would talk about Edna Blair.

“Sure seems your mama has a lot of time on her hands. What does she get to all day?”

“Well, we know it’s not housecleaning.”

The truth was, Edna Blair was sick. Diabetes. The disease made her fat and blind and ambivalent to housework, neighborhood gossip, and rules of decorum. Aneita Jean tried to curry her mother’s favor by cleaning feverishly. She scrubbed the floors and sills, scrubbed everything really, until you could lick it and taste nothing but wood. But Edna didn’t care about dirt or stains or having floors clean enough to lick. She didn’t mind much in fact, not rain, or owning only one dress, or a hole in a boot. She was content to lounge on the porch in her colossal wicker love seat, eating cake and sucking the icing off her fingers.

Edna told no one about her illness because she knew how pity hollowed a person out. She had felt it from her own mother, Mewey, who had unloaded her like bruised fruit on the first willing taker, love being a luxury someone as damaged as her unhealthy daughter couldn’t afford.

Edna had been working as a court typist when she met her future husband. He was selling shoes. Mewey took one look at Andrew in his sharp wool suit and decided here was the man for her baby girl. Andrew married Edna because, sickly or not, she was beautiful, with loosely pinned hair that curled around her ears like ivy. Besides, dating was not his priority. Edna had other ideas, but she knew she could not disappoint her mother. It didn’t matter that adoring Andrew Blair was about as easy as falling up a well.

“You’re sick, girl. Who else is going to marry you?” Mewey said.

And so, married off, Edna headed upriver to join a new class of people. She and Andrew were wed in Columbiana County on August 26, 1913. After the wedding, Edna did her best, but Andrew Blair was not one for pleasure. He was temperamental, moody, and prone to meanness. He was also exceptionally handsome—tall and svelte, with a thin nose, wide-set eyes, and blond hair, which he slicked back with vigor. He had a plump bee-stung mouth, which shamed him. As soon as he was able, he grew a mustache to cloak his lips, and any remaining trace of carnality. He shaved it once, and it made my grandmother cry, so shocking was it to see his beautiful lips.

The Blairs’ first apartment was in Wheeling, West Virginia, a flat in a line of brick row houses, two stories high, with cement porches and shuttered windows. Each floor held one apartment, as did the basements. Because the interiors were cramped and dark, people kept outside as much as possible, congregating on the porches, legs swung over the ledges, or sitting shoulder-to-shoulder on the stoop. The tight quarters left no room for privacy, an irritation to Andrew, so the Blairs moved to Chester as soon as they could afford to.

There, people quickly learned that Andrew Blair was a stern whip of a man, a taciturn Scot purged of any inclination toward revelry by that train that had flattened his mother and knocked his father into a lifelong wall of silence. The only things that brought Andrew to life were music and his garden. He was known for growing the tallest peas in the valley and for his skits in the pottery minstrel shows, where, behind his blackened face and floured lips, he felt safe enough to sing, dance, and run his body hobnobby-wild across the stage.

There are two photographs that capture Andrew best. In the first, he is sitting cross-legged on a tree stump. The trees behind him are leafy with the outgrowth of late summer, their wilting shadows dense and far-reaching. Despite the season, Andrew is dressed in a long-sleeved dress shirt, cuffs ironed and buttoned. His trousers are wool, also with ironed cuffs. His boots are snugly laced to the ankles and his tie is knotted up around his throat. On his head rests a wool cap.

His hands are loosely folded in his lap, arranged like flowers. His face is stiff and marked by measured boredom. The net effect is prim sophistication, a look wildly out of place in the rural West Virginia summer heat, or in West Virginia at all, for that matter. Here is a man who has forgotten, or is trying his damnedest to forget, that he is perched atop a stump in the middle of a disregarded nowhere.

The second photo was taken in the fall. Andrew is again in formal attire, this time a wool suit. He has been photographed from the feet up as he lies prostrate atop a stone wall. It’s a silly angle, one obviously contrived in the fun of an afternoon at the park, a horsing-around sort of snapshot, except that Andrew is not smiling. He has assumed the position of a goofy young man, but his face will not relent. It remains a tight mask of thinly veiled annoyance. The soles of his shoes appear to have been, God love him, scrubbed.

When Aneita Jean was born, her father held her at arm’s length.

“Well,” he said after a time. “She’ll do.”

It was Andrew who decided to name my grandmother Aneita Jean after his sister Jean, whom everybody called “Jean Jean the Beauty Queen.” In retrospect, this may have been a mistake, but that did not stop Aneita Jean from later naming her own daughter Jody Jean, nor did it stop Jody and her sister Jennifer from naming their daughters Jean. Names are history, constant and resonant, and so what if the first Jean turned out to be a loon.

Jean Jean the Beauty Queen was married to Robert Woods, a navy captain of some note in Pittsburgh high society. She had a daughter, Dorothy Jean, seven years old, who had flashing green eyes and auburn ringlets that bounced beside her cheeks. They were an abundantly happy family, and so it was a full-on tragedy when Robert’s fighter-bomber went down in the ocean, leaving them alone. They managed for a few months, but things were never quite square. Jean Jean took to her bed or to walking around the house, circling like a ghost, nodding her head to no one. Dorothy was left alone, and she, too, grew quiet. Then spring arrived. The sun shone hot and clear and Jean Jean decided she would drive her daughter to the beach in Maryland. There, they dug sand castles and played guess which hand has the button. Dorothy ran along the shore and Jean Jean chased her, scooping her up from behind, making Dorothy squeal. For lunch, they ate bologna sandwiches and oranges. Then, after a rest, Jean Jean the Beauty Queen took her daughter’s hand and walked into the ocean.

“We’re going to see Daddy,” she said.

By all accounts, it was ponderous going, but she persisted. Dorothy Jean struggled and broke free, making it to shore and into the arms of bewildered strangers. Her mother kept on. Never looking back to her child, she pressed farther and farther into the sea, her body bobbing in and out of view like a buoyed cork. The last thing Dorothy Jean saw was a froth of white sliding over her mother’s hair, as if she were removing a slip.

After the funeral, seven-year-old Dorothy was sent to live in Indiana with her uncle Rob and his wife, Mildred. No one mentioned her mother until a generation later, when time had made it safe to talk about.

“Crazy, she was,” says my grandmother. “Like me.”

Grandmother had met Uncle Rob and Aunt Mildred in Indianapolis the summer before she turned ten, a year before cousin Dorothy would move there.

“I’m not saying they were dull people, just that they were dull people,” Grandmother joked.

Aneita Jean and her father drove the Nash Ambassador to Indiana. Not many people in Chester, West Virginia, had cars, and the Nash, a blue-and-orange beauty, wasn’t driven all that much. Usually, it sat idle in the shed, a monument to Andrew Blair’s hard work. The car was intended for special occasions, like the Fourth of July parade, or hauling ware to sell on the road. So when her father announced that the two of them would be taking the Nash to another state, Aneita Jean nearly fainted.

It was strangely humid the weekend the two of them set off for their visit. They were sweating before they left Phoenix Avenue.

“Daddy …”

“Too warm to talk, Jeannie,” her father snapped, sitting tall as corn in his suit and tie, even though it was hot enough to make the pavement bubble.

They drove in silence. Aneita Jean wore a starchy dress, which clung to the backs of her knees. She tried to peek underneath to see if it was staining, but she didn’t want her father to notice, so mostly she sat very still and counted farm silos. These were the safe years, the comfortable years between father and daughter. Before the girl starts looking too much like her mama and dragging boys home like baggage. Before the father sees her growth and feels his age and his helplessness and it roils in his stomach like a beehive. No, those times would come later, replete with whippings and restrictions and all the other futile gasps of a parent losing control of his child.

Rob and Mildred had just married, and the two wanted to celebrate with Andrew. On the drive, Aneita Jean imagined all sorts of revelry—fancy dinners and grown-ups sipping wine. As it turned out, Mildred and Rob were as festive as her father, and the celebration consisted of apple juice and chewy pork chops eaten at home.

Mildred barely talked, just a word here and there, followed by a dry sniff to show her disapproval. Upon meeting Aneita Jean, she sniffed quite a bit, first at her dress (which was sodden), then at her hair (curls steamed to the back of her neck), then at her manner (inquisitive), which she found inappropriate for a child. The sniffing was particularly effective, as Mildred’s nose was as pointy as a pencil.

Anteater, thought Aneita Jean.

After dinner, they all took a walk around the neighborhood. The houses seemed so big to Aneita Jean, if only because you could see for miles in every direction. There were no hollers or cricks in Indiana. The world was smooth and endless.

As they strolled, Aneita Jean began to limp. Something was hobbling her foot. She tried to hide her pain, but her father noticed.

“Stand up straight,” he said.