Полная версия:

Tribes with Flags: Adventure and Kidnap in Greater Syria

TRIBES

WITH

FLAGS

Adventure and Kidnap in Greater Syria

CHARLES GLASS

Dedication

For Julia, Edward, George, Hester,

Beatrix and Fiona

and to the memory of Mouna Bustros

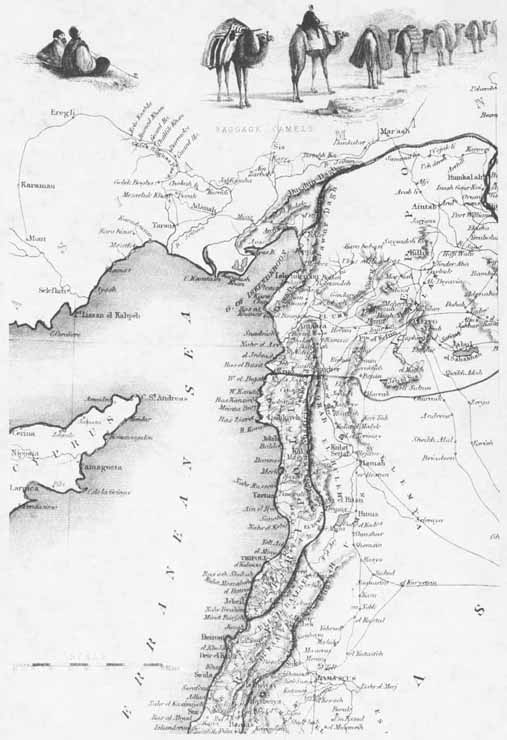

Detail from “Syria”, Tallis’ Atlas, 1841

Epigraph

“A man may find Naples or Palermo merely pretty;

but the deeper violet, the splendour

and desolation of the Levant waters

is something that drives into the soul.”

James Elroy Flecker

Beirut, October 1914

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Frontispiece

Epigraph

New Introduction by the Author

PART ONE

1The Legacy of Alexander

2The Army of the Levant

3The Last Ottoman

4Minarets and Belfries

5No-Man’s-Land

PART TWO

6Six-Star Brandy

7Where Armies Failed

8A Consular City

9The Survivors and the Dead

10The Village of a Pasha

11The Road

PART THREE

12The Old City

13Meleager’s World

14This Bad Century

15Queen of the Desert

16Provincial Loyalty

17Enemies of the Goddesses

PART FOUR

18Excursions

19A Blood Feud in the Mountains

20Foul is Fair

21The Ghetto

22Monks and Martyrs

23The Family and the Plain

24The Slumber of the Dead

25Disrespectful Dancing

26The Last Day

PART FIVE

27The Black Hole

28Recalled to Life

About the Author

Also by Charles Glass

Copyright

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

Twenty-five years ago, I traveled by land through what geographers called Greater Syria to write a book. The journey began in Alexandretta, the seaside northern province that France ceded to Turkey in 1939, and meandered south through modern Syria to Lebanon. From there, my intended route went through Israel and Jordan. My destination was Aqaba, the first Turkish citadel of Greater Syria to surrender to the Arab revolt and Lawrence of Arabia in 1917. For various reasons, my journey was curtailed in Beirut in June 1987. (I returned to complete the trip and a second book, The Tribes Triumphant, in 2002.)

The ramble on foot and by bus and taxi gave me time to savor Syria in a way I couldn’t as a journalist confronting daily deadlines. People loved to linger over coffee and tea, play cards, and talk.

Many of the civilian members of the Baath Party, whose founders claimed to believe in secularism and democracy, deserted its ranks when the party took power in 1963. They rejected the militarization of the party, which kept power not through elections but by force of the arms of its members within the army. Among those who left the party was the father of Rulla Rouqbi. I met his daughter a few weeks ago at the hotel she manages in Damascus. Faissal Rouqbi had died in April 2012, and this explained why the attractive fifty-four-year-old was dressed in black. A vigorous supporter of the revolution that began in Syria a year earlier, she believed hers was the same struggle her father had waged against one-party military rule.

“I was questioned twice by the security forces,” she told me in the hotel’s coffee shop, which looks out onto a busy downtown street. “They did it just to show me they know what I am doing and they are here.” She said that, because young dissidents gathered in her coffee shop with their computers, the police cut the hotel’s WiFi connection. Nonetheless, several young people were there discussing the rebellion—much as their forefathers did in the old cafés of the souks that the French destroyed to put down their revolts—over strong Turkish coffee or newly fashionable espresso.

The rebellion against tyranny was by 2012 turning into a sectarian and class war that threatened to destroy Syria for a generation and drive out those with the talent, education, or money to thrive elsewhere. Neither side spoke of conciliation. The endgame for each was the destruction of the other. Foreign backers appeared, as in Lebanon from 1975 to 1990, to encourage confrontation in their own rather than Syrian interests. Nothing had changed since Britain and France occupied the Ottoman provinces of Greater Syria during World War I.

A glimmer of hope came from the economist Nabil Sukkar, formerly with the World Bank. “The opposition is not going to retreat,” he told me in Damascus. “The stalemate could last to 2014.” Bashar al-Assad’s term of office was scheduled to end in that year, when, Sukkar believed, he could stand down without losing face or having his Alawite community punished. He continued, “For [Kofi] Annan to succeed, there has to be compromise from both sides. The regime must stop killing, and the opposition must stop smuggling [arms]. And foreigners must stop sending arms. Then there can be a cease-fire and a transition government.” However unlikely that seems today, it could work if Russia and Iran compel the regime and the United States, Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Qatar push the opposition to achieve it. Otherwise, Syrian will fight Syrian—just as the Lebanese did—in what the respected Lebanese journalist Ghassan Tueini called “a war for the others.”

Three great fears dominated the uprising of 2011 and 2012: that the regime would emerge stronger and more violent; that Syria’s traditional tolerance and respect for people of different religious and ethnic communities would falter if a strongly Sunni Muslim fundamentalist regime replaced it; and that, with neither side able to destroy the other, the conflict would escalate and linger as Lebanon’s did. Nowhere were these fears more apparent than in my favourite Syrian city, Aleppo.

Archaeologists believe that human beings settled on the hilltop that became Aleppo, on the plains two hundred miles north of Damascus, around eight thousand years ago. Cuneiform tablets from the third millennium BC record the construction of a temple to a chariot-riding storm god, usually called Hadad; mid–second millennium Hittite archives point to the settlement’s growing political and economic power. Its Arabic name, Haleb, is said to derive from haleb Ibrahim, “milk of Abraham,” for the sheep’s milk the biblical patriarch offered to travelers in Aleppo’s environs. Successive conquerors planted their standards on the ramparts of a fortress that they enlarged and reinforced over centuries to complete the impressive stone Citadel that dominates the city today.

“It is an excellent city without equal for the beauty of its location, the grace of its construction and the size and symmetry of its marketplaces,” wrote the great Arab voyager, Ibn Battutah, when he visited in 1348. During the Renaissance, Aleppo was Islam’s third most important city, after Constantinople and Cairo. The modern Lebanese historian Antoine Abdel Nour praised it in his Introduction à l'Histoire Urbaine de la Syrie Ottomane: “Metropolis of a vast region, situated at the crossroads of the Arab, Turkish and Iranian worlds, it represents without doubt the most beautiful example of the Arab city.” Its beauty reveals itself in the elegance of its stone architecture, redolent of historic links to Byzantium and Venice; and in the diversity of its peoples—Arabs, Armenians, Kurds, eleven Christian denominations, Sunni Muslims, a smattering of dissident Shiite sects from Druze to Ismailis, ancient families of urban patricians, and peasant and bedouin immigrants from the plains—that make it a microcosm of all Syria.

Documentary records of Ottoman Turkey’s dominion over Aleppo from 1516 to 1918 portray communities of Muslims, Christians and Jews living in the same neighborhoods. In Tunis, Jews were obliged to rent living space, by contrast, Aleppo’s governors imposed no restrictions on house ownership by members of any religious group or by women. It was not unusual for large mansions to be divided into apartments in which Muslim, Jewish and Christian families dwelled with little more than the usual rancor that afflicts neighbors everywhere. Unlike more xenophobic Damascus, Aleppo encouraged Europeans to trade and dwell within the city walls. The European powers, beginning with Venice in the sixteenth century, established in Aleppo the first consulates in the Ottoman Empire, to guard the interests of their expatriate subjects. Descendants of Marco Polo, the Marcopoli family, retained the office of Italian honorary consul well into the twentieth century.

In a neglected corner of the old Bahsita Quarter, behind several old office buildings, stands a monument to Aleppo’s historic mélange. The Bandara Synagogue was built on a site of Jewish worship that predates by two centuries the AD 637 Arab-Muslim conquest of Aleppo. Its courtyard of fine cut-stone arches and domes resembles the arcaded cloister of the nearby Al-Qadi Mosque. The Jewish community of Aleppo, like its larger counterpart in Damascus, gradually made its way to New York after the founding of Israel. The last Jews departed en masse in 1992, when then-President Hafez al-Assad lifted restrictions on their emigration. Suddenly, Damascus and Aleppo were bereft of an ancient and significant strand of their social fabric. The synagogue, restored by Syrian Jewish exiles, is the forlorn relic of a community that thrived for ages before vanishing under the weight of war between Syria and Israel. It is also a harbinger of what Aleppo’s Christians apprehend as their fate if the latest uprising leads to all-out war or domination by Sunni Muslim fundamentalists.

“Am I worried?” Archbishop Mar Gregorius Ibrahim Yohanna, metropolitan in Aleppo of the Syrian Orthodox Church asked rhetorically. “Yes. Am I afraid? No.” The archbishop’s concern is widespread among Christians of both Arab and Armenian origin, who claim to make up nearly 10 percent of Aleppo’s 2.5 million people. (Their proportion, while half what it was fifty years ago, may have halved again to 5 percent, owing to Christian emigration, a low birthrate, and the steady influx of rural Muslims into the city. The Syrian government does not publish statistics by religion.) The archbishop, whose PhD thesis at Britain’s Birmingham University was on Arab Christianity before Islam, insisted that Christians should not take sides between the government and its opponents. Unlike the Christians of Lebanon, Syrian Christians do not have their own political parties or armed militias. Mar Gregorius elaborated, “The only weapon we can use is to leave the country. I don’t believe it’s right.” Those who are leaving, even if only for the duration of the conflict, provide a rationale similar to the one Syrian Jews gave me in 1992: they were escaping, not the Assad regime, but the Muslim fundamentalists who might overwhelm it.

“Many Christians have left,” Dr. Samir Katerji, a fifty-eight-year-old architect and member of the Syrian Orthodox Church, told me. “Many Armenians have bought houses in Armenia. Even the Muslims are leaving.” Katerji, who designed the amphitheater for outdoor films in the Aleppo Citadel, had “visited my aunt’s house,” a local euphemism for going to prison, several times. The security services arrested him for his outspoken criticism of the Assad regime and the Baath Party. “I feel the majority of the Syrian people is against this government,” he told me over a drink in his office. “It’s a very bad government. Governments and armies everywhere are dirty, even the Vatican.” While lamenting Syria’s lack of basic political freedoms, including free speech and assembly, he acknowledged, “We have social freedom. We are free to declare our thoughts and beliefs and to practice our Christianity.” He condemned murderers within the regime, but had no faith in the regime’s armed opponents: “Inside the opposition are also murderers who will not allow stability.”

Instability brought on by armed rebellion, mass demonstrations, regime violence, and economic sanctions has unsettled Syrian’s many minorities. The Alawites are concentrated in the west near the Mediterranean, the Kurds in the east beside the Euphrates, and the Druze in the south in Jebel ed Druze, so those minorities have territorial bases from which to negotiate their survival no matter who takes power. (In Beirut, just before I crossed the border to Syria, Walid Jumblatt told me he had advised his fellow Druze in Syria to join the rebellion. “They swim in a Sunni sea, not an Alawite sea,” he said, mentioning what happened to those Algerians who sided with the French during the war of independence: many were killed and the rest fled to France.) The Christians, however, are thinly dispersed among Aleppo, Damascus, Wadi Nasara, Qamishli, and other parts of the country. Having witnessed the flight of two million Iraqi Christians to Syria during Shia-Sunni fighting after 2003, they anticipate a similar exodus from Syria if the anti-regime rebellion descends into a tribal war between Alawites and Sunnis that will trap them in the middle. Reluctant to leave their ancestral homeland, which they regard as Christianity’s cradle, they are confronted with demands from both the revolutionaries and the regime to declare themselves. They have resisted as communities so far, although individual Christians are fighting for and against the regime. The Armenian Catholic archbishop of Aleppo, Monsignor Butros Marayati, told me, “We cannot say one side has truth and the other does not, because both sides have faults.” He added that 171 Armenians in Homs have died as members of the security forces or in cross fire, but not as deliberate targets of either side.

Minorities who benefited from the policies of the Alawite minority regime hesitate to turn their backs on it during a time of crisis. Moreover, many Christians view the opposition’s driving force, despite its many secular and liberal adherents, as Sunni fundamentalism battling Alawi upstarts. The fundamentalists, they believe, will deprive them of social freedom in the name of political liberation. An Armenian high school teacher, whom I have known for many years, became uncharacteristically loquacious when explaining her support for the Assad regime:

I’m free. I am safe. … “You’re a kafir [unbeliever]”: I have not heard that phrase for thirty years. At the school, some of my friends are Muslim Brothers. They respect me, and I respect them. Who is responsible for that? … Look at this terror. Is this what Obama wants? Is this what Sarkozy wants? Let them leave us alone. If we don’t like our president, we won’t elect him. This is from a woman who is sixty years old, and I’ve been free for thirty years. I should be afraid to go out? I should cover myself? Women should live like donkeys? … We are citizens. We are equal. Everybody is free with his religion.

She, along with many other Aleppines in the past year, has installed a steel-reinforced front door to her house. This is one sign that the security she and many other Christians felt under Assad père et fils, the regime’s primary justification, is dissipating. Tales of the rape, kidnapping, and murder of Christians in Homs, the city halfway between Aleppo and Damascus that has become this revolution’s Barcelona, have created unease among their coreligionists throughout Syria. In Aleppo, bombs that damaged security force centers took with them nearby Christian apartments, schools, and churches.

Aleppo is tranquil most of the time. There are no soldiers on the streets, and the nightlife that was suspended out of caution in the first months of the rebellion has returned to downtown and the outdoor cafés along Azizieh Square. But, Aleppines of all faiths wonder, for how much longer?

On April 13, Good Friday for the Orthodox churches, I spent the morning walking through the Aleppo Citadel and drinking coffee below its main gate. Families traversed a stone footbridge, supported by seven Roman arches over a dry moat, from a pedestrian plaza at ground level several hundred feet to the Citadel entrance. On the stone walk in front of a row of outdoor cafés, a man in a Nike baseball cap played soccer with his son and daughter, about three and four years old, also in baseball caps. Another little boy with an ice cream cone in one hand chased his father, a tall young man in jeans and tennis shoes. A few families were having breakfast, others coffee and soft drinks. A woman wearing a Superman blue sweater and a matching scarf over her hair promenaded while holding a pink balloon at the end of a bit of string. Beside her were two young women, probably her daughters, in tight slacks, their hair loose on their shoulders. A man pushing a kiosk on bicycle wheels sold cotton candy. The sweet aroma of apple-scented Persian tobacco, smoked through ornate water pipes by women and men, swam though the air. In the dry moat, a half dozen preteens played soccer. Since the conflict began in March 2011, no tourists have checked into the ancient hospital that is now the five-star Carlton Citadel Hotel. Its restaurant terrace, however, filled with Syrians at lunchtime.

In the spring of 1987, also at Eastertime, I made notes in one of these cafés as I was doing twenty-five years later. Thousands of Christians were visiting one another’s churches and exchanging flowers, without provoking so much as an awkward glance from their Muslim neighbors. I was worried about finishing this book, thinking about the next stage of my journey to wartime Lebanon and whether it would be safe in that era of kidnapping foreigners. Syria then seemed solid, unchanged and unchangeable, like the Soviet Union that provided what little international backing it had. The Assad regime had been in place since 1970, the Alawite minority since a coup in 1966, and the Baath Party since 1963. The combined military-party-family structure had survived multiple assaults: the two-year Muslim Brotherhood uprisings in Aleppo and Hama that ended violently in the spring of 1982; Israel’s destruction of its air force and armor that summer in Lebanon; and an attempted putsch by the president’s brother in 1983. Syria’s regime, founded on the primacy of the single party and the army with its intelligence apparatus, resumed control of Lebanon with American approval in 1985, and acquired a Lebanese ally, Hezbollah, whose steady humiliation of the Israeli Army in south Lebanon allowed it to enjoy reflected glory.

For all his political strength and canniness, Hafez al-Assad had a weak heart that made his mortality a source of opportunity for his enemies (Israel Radio announced his death about fifteen years early) and apprehension by his friends. He groomed his toughest, oldest son, as did his fellow dictators in the hereditary republics of Iraq, Egypt, and Libya, to assume power as naturally as the crown princes of Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Oman, and Qatar. That child, Bassel, died in a car crash in 1994, so a younger son, Bashar, was drafted from his London medical studies to assume his brother’s place as heir to the throne. On his father’s death in 2000, Bashar, with his British-born wife at his side, promised reforms that he failed to implement. The Baathist slogan, “Unity, progress, socialism,” still plastered on the Citadel in 1987, was already fading from the assaults of sun and rain. Twenty-five years later, it has disappeared altogether.

Syrians seemed in 1987, if not content, reconciled to a fate that was preferable to the regime of terror they observed in Saddam’s Iraq to their east and the anarchy of Lebanon in the west. (The Lebanese Druze leader, Walid Jumblatt, said of Beirut’s gunmen at the time, “They don’t even obey the law of the jungle.”) The type of dissident intellectuals that Saddam Hussein would torture to death before assassinating their families would in Syria receive a dressing-down from security officials and sometimes a few weeks behind bars to restore them to the path of Baathist righteousness. Torture was reserved for more serious dissidents, the army’s would-be coup-makers and, after 2001, suspected terrorists discreetly transferred to Syrian custody by the CIA. It was cruel; it was efficient; and, until students demonstrated against it in the remote southern border town of Dera’a in March 2011, it was as impregnable as Aleppo’s Citadel.

When Dera’a’s students opened the gate of protest, everyone became a critic of the regime. Even servants of the state complained of corruption among the president’s immediate family and the security services’ use of surveillance, informers, detention and torture to maintain elite privileges. The foreign media officer at the Ministry of Information, an attractive young woman named Abeer Al-Ahmad, surprised me in April 2012 by offering introductions to “opposition leaders.” This would have been unimaginable in 1987, even if they were merely the “official” opponents running in May’s parliamentary elections. The regime allowed the campaign, along with a new constitution and ostensible suspension of the long-standing state of emergency, to meet some of the demands of the real opposition led for the most part by young people in the streets.

The young, born too late to have seen the regime’s suppression of the Muslim Brothers’ rebellions in Aleppo and Hama between 1980 and 1982, came of age during an era of superficial reforms. After Bashar-al-Assad succeeded his father in 2000, government primary and high schools abandoned military-style uniforms for students and granted everyone access to modern telecommunications. (Under his father, even international news agencies had needed government permission to install a fax.) This illusion of liberty seemed to whet an appetite for the substance. Youngsters, who did not share the older generation’s experience of prison and torture, ignored their elders’ caution by calling on other youngsters to join them the streets.

Orwa Nyarabia is a thirty-five-year-old film producer, who among other activities organizes the Damascus Film Festival. He has worked with younger colleagues to organize peaceful demonstrations and street theater to undermine belief in the all-powerful, all-knowing regime. He confesses to embarrassment that he has avoided arrest while all the youngsters in his office have spent short periods in jail. For him, the protests that erupted in Dera’a last year were not surprising. “It’s been cooking for a while,” he told me in the coffee shop of Damascus’s Omayyad Hotel. “In my domain, documentaries, we showed films on dictatorship in Burma and China. The censors passed it, but the audience came out discussing Syria.” When his film festival asked audiences to vote for the best film in 2008, the newspaper headline was, “First Free Vote in Syria.” He said, “The regime blackmailed us with accusations that we were about political provocation. I told them I’m a total liberal businessman.”

Most opponents of the regime, apart from the “official” candidates, dismissed the May elections as irrelevant. Most recall a joke told about the referenda staged every five years by Hafez al-Assad, to endorse his tenure. An official brought him the results: “Mr. President, you have won again with 99.9 percent approval. Only 450 people voted against you.” The president glowered. The official pleaded, “What more could you want?” The president replied, “Their names.”

Nyarabia said that when young people in Dera’a campaigned to ban smoking in public places as far back as 2005, “It was really to have a campaign.” The opposition is finding its way, learning from mistakes and making new ones. It lacks the experience of the regime, as well as the regime’s armory of control. “Two weeks ago, I was talking to the leader of a militia,” Nyarabia, who is half Alawite and half Sunni, said. “There is a danger of becoming sectarian. They are becoming anti-Alawi rather than anti-regime.” The reason for this, he and his friends believed, was that Saudi Arabia provided arms and funds to those closest to its own Wahhabi ideology rather than to liberal democrats. This, combined with threats from Syrian mullahs broadcasting on satellite television from Riyadh, frightens the minorities more than anything else about the opposition.