Полная версия:

The Tribes Triumphant: Return Journey to the Middle East

CHARLES GLASS

The Tribes Triumphant

RETURN JOURNEY

TO THE MIDDLE EAST

‘When the government is unable to provide for their safety, they will band themselves into tribes.’

SIR JOHN BAGOT GLUBB,

Britain and the Arabs: A Study of Fifty Years, 1908–1950

DEDICATION

The author dedicates this book

to his friend Noam Chomsky

and to the memory of another friend,

Edward Saïd.

EPIGRAPH

‘Between the Arabian Desert and the eastern coast of the Levant there stretches – along almost the full extent of the latter, or for nearly 400 miles – a tract of fertile land varying from 70 to 100 miles in breadth. This is so broken up by mountain range and valley that it has never all been brought under one native government; yet its well-defined boundaries – the sea on the west, Mount Taurus on the north, and the desert to east and south – give it unity, and separate it from the rest of the world. It has rightly, therefore, been covered by one name, Syria.’

REVEREND GEORGE ADAM SMITH

The Historical Geography of the Holy Land (1894)

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

EPIGRAPH

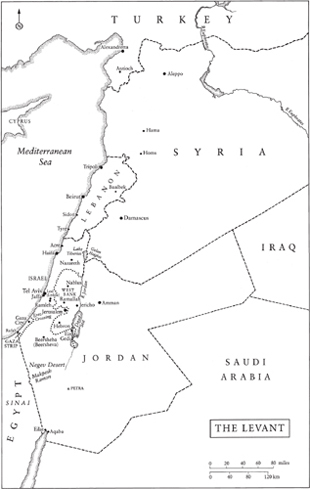

MAP

1 Imperial Wars

2 Aqaba, Fourteen Years Late

3 Royal Cities

4 Over Jordan

5 O, No, Jerusalem!

6 Gaza

7 Jerusalem, from the West

8 Return to Gaza

9 The Desert

10 Jaffa and Suburbs

11 The North

12 Damascus Is Burning

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ALSO BY THE AUTHOR

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

MAP

ONE

Imperial Wars

‘It is the atmosphere in which seers, martyrs, and

fanatics are bred.’

REVEREND GEORGE ADAM SMITH

The Historical Geography of the Holy Land (1894)

11 September 2001

IT WAS NOT ENOUGH to sail or drive to Aqaba. I had to take it by force, galloping with Arab tribal warriors to the gates of its ancient fortress, storming the citadel and raising the colours above the battlements. The Ottoman Red Sea garrison would surrender, as it had to Captain T. E. Lawrence in the summer of 1917, or my sword would taste the defender’s flesh. All Syria – its sandy plains and snowy summits, oases and castles, nomad camps and ancient cities, fractious and competing believers in the One God – would lie open to my advance.

Years later, of course, I might regret it. Lawrence of Arabia certainly did. Was Johnny Turk any worse to the Levant than his successors – Britain, France, America and the advocates of Zionist colonization? A region that had remained united for four centuries within the Ottoman Empire – and for many more Hellenized centuries before that – was divided, abused and rendered impotent. Lawrence himself acknowledged his betrayal of the Arabs, as America’s Lawrences later confessed their treachery to the brave Afghan tribesmen who had beaten back the Soviet empire. Foreign adventurers promising freedom to the earth’s wretched – among them the Arabs of 1917 and the Afghans of the 1980s – knew in their souls that what they offered the native warrior was so much dust. Empires employed the indigenes to destroy rival empires: the British vanquished the Ottomans, as America did the Soviets, with local trackers, guides and killers.

I was halfway from London to Aqaba, by train and ship, when massacres of my countrymen in the United States altered the nature of a journey I had been contemplating for fourteen years. My intention was to complete a Levantine adventure. In 1987, while on my way from Alexandretta in southern Turkey to Aqaba in Jordan, politics stopped me dead. In Beirut, a Shiite Muslim militia, the Hizballah, cast me into chains. After my escape, I returned home to my family in London rather than resume the journey south. The Hizballah had kidnapped many other foreigners for political ends; and it had nurtured the suicide bomber, that mysterious and sometimes anonymous figure who expelled the US Marine Corps and the Israeli occupation forces from Lebanon. The tactic of the human delivery mechanism reached its horrible fruition in the wilful murder of thousands of innocent human beings in New York, Washington and western Pennsylvania on 11 September 2001. I was in Florence when it happened.

After watching the World Trade Center’s towers collapse on Italian television, I called friends in New York’s downtown. The telephone lines were down. It did not occur to me that the mass murders in the United States would affect my plans, until Julia, my sixteen-year-old daughter, called from England. Seeing the destruction of a solid structure from which we had enjoyed the Manhattan vista the previous summer shocked her. Making a connection that I had not, she feared that the events we had witnessed via our televisions would have an impact in the Middle East. American administrations had bombed Muslim countries for less, and Julia worried that people in the Arab world would attack American citizens in revenge for American vengeance. I promised her that, if I anticipated any threat to myself, I would come home.

I had already reserved a wagon-lit that night to Brindisi on Italy’s east coast and berths on ships from Brindisi to Greece and Greece to Port Said. That would leave time to cancel if an outraged Arab world reacted by killing or kidnapping the Americans in its midst. Julia’s entreaties had the effect of making real to me the horrors that I had yet to absorb in the preceding hours. Her life had perhaps made her more sensitive to political danger than most children in the complacent West. Political-religious revolutionaries in Lebanon had abducted her father when she was two. The father of two of her close friends, British military attaché Colonel Stephen Saunders, had been assassinated in Athens by the notorious November 17th group two years earlier. As she worried for me, I thought of my older son, George, in Turkey. Although no harm was likely to reach him there, I called him, as Julia had me. I asked him to return to Rhodes, where my ship was stopping. We could sail on together from there. Thus, under threat, we seek refuge among our own tribes – in this instance, among fellow Christians in Greece – lest we offer targets to the other side. Rhodes, itself a haven to Knights Hospitaller driven from the Holy Land in 1309, lay close to the Turkish shore on the frontiers where Islam brushed against Christendom. No harm came to any Westerners in Turkey.

On that September day, I was in the Florentine house of friends, Adam and Chloe Alvarez, set within the walls of a garden so vast that it is best described as a wilderness. Weighing on me were Julia’s fears, New York in chaos, the impossibility of telephoning friends there, the reports of more and more deaths and the brutality of the attacks. In the Alvarezes’ sitting room, Britons and Italians alike worried for New York friends while watching, again and again, the collapse of the Twin Towers. Unable to endure another replay, I walked out to a cypress grove at one end of the garden. In the Mediterranean, cypresses grow in graveyards to point the soul’s way to heaven. People in my native land were dying and in agony and in fear. It would not be long before American anger would manifest itself in the deaths of Muslims. I must have been about to weep, when someone called from the house to say the television had more news. That was before we knew how many had died, who had done it and why.

An Italian woman I had loved years before called me at the Alvarezes’. The deaths in New York, where she had once lived, left her too distraught to see me off, as planned, at Santa Maria Novella Station. We had said enough sad goodbyes when we were in love. I left without a farewell, boarding the train alone like a spy skulking into the night and not as a soldier dispatched to the front with farewell kisses. Later, snug in my bunk reading about nineteenth-century Palestine, I answered my cellphone. My younger son, Edward, was calling from England. What were my plans? Would I be safe? He was seven when Hizballah captured me.

The next day, on an empty beach near Brindisi, I wrote, ‘What am I to do? I’m commissioned to write a book in the Middle East, and I have to go. But I don’t want to cause hurt to my children, as I had in 1987. I’ll see when I get to Rhodes.’ In 1987, I embarked on a journey through all of geographic Syria to write Tribes with Flags. Beginning in Alexandretta, the Syrian Mediterranean port that the French ceded to Turkey in 1938, in the spring, I had intended to reach Aqaba on the Red Sea – after exploring Syria, Lebanon, Israel and Jordan – in time for the seventieth anniversary of Lawrence’s victory in July. But, by July, I had already been a captive of the Shiite Muslim Hizballah movement for a month in Beirut. After my escape on 19 August, I did not complete the journey. Finishing something that I started fourteen years before was no excuse for making my family suffer again. I would go, but I would avoid risk

Boarding the Maria G. of Valletta that evening in Brindisi harbour brought me back to the Levant. An old woman, who looked as if she had not left the farm once during her sixty-odd years, stepped ahead of me. In a rough cotton dress, the tops of her dark stockings rolled at the knees and a scarf knotted around her white hair, she could have been a peasant from any Mediterranean village. Faced with a moving escalator, she stared as if at a ravenous sea monster. A Greek crewman took her arm. She fell, and the sailor righted her with a quick shove. She trembled while the metal stairs carried her towards the landing. At the top, she refused to budge. I stepped back to avoid crashing into her, but to no avail. The woman stepped on my big toe, from which a chiropodist had only recently removed an in-growing toenail. Passengers bashed into me from behind, and we were all tumbling over one another. The crewman pulled the woman out of our way. She waited, petrified, unwilling to risk the second ascent to A deck. The sailor forced her up to the top, where several other sailors shifted her like luggage. On A deck, she stepped on my toe again. How could this Italian matron have lived for more than sixty years without confronting an escalator?

That evening, while the sun descended on Brindisi harbour, I sat on the aft deck with a book and a drink. The old woman, restored to safety, stopped at the rail with her husband. They were speaking Italian. ‘These Greeks,’ she said in disgust of her fellow passengers, ‘are primitivi.’

The sun went down, and Brindisi’s lights went up. An aeroplane took off in the north. It ascended slowly and seemed to hold still in the sky. Who on that day, seeing an aircraft on the wing, did not imagine for an instant what he would do to save himself if it flew straight for him? The Maria G. of Valletta, its flag flying the Maltese Cross that once terrorized the infidels of the East, sailed six minutes early at 7.54 in the evening. On the eight o’clock news of the BBC World Service – a small transistor radio has accompanied me for thirty years – a newsreader predicted, ‘Life for Americans will never be the same.’ I did not want to believe him.

Slow Boat to the Levant

As the ship approached Patras the next morning, the BBC World Service reported that Israel’s prime minister, General Ariel Sharon, had sent Israeli forces to attack Jericho, a Palestinian city in the Jordan Valley. Sharon, a lifelong Arab fighter, appeared to be making use of the American declaration of war on terrorism. No longer would General Sharon be attacking Arabs to kill them, to prolong Israeli occupation of the West Bank, to plant more settlers to displace more Arabs and to eliminate resistance to illegal military occupation. From then on, he would be fighting terror arm in arm with America.

At nine in the morning, winches lowered guide ropes to tie the Maria G. to the quay in Patras harbour. The bar in which I’d had a cold espresso was emptying, as passengers lost themselves in the exit queues. Only the canned jazz remained. This was Patras, Greek Patras, my first Levantine port. The town of squat apartment blocks and storage sheds was uglier and more functional than the colourful, tourist-friendly seaports to the west, St Tropez, Portofino, Porto Ercole. The East had abandoned beauty for high returns – minimum investment for maximum return. The new world of the East was more hideous than it had been on my 1987 tour, but it was more convenient: mobile telephones, cash dispensers, the end of exchange controls and more relaxed customs regimes. Ashore in Patras, I withdrew drachmas from a cash machine, took a taxi to the central bus station and boarded the bus to Athens.

If the Levant began at Patras, the Third World opened its doors at Piraeus, Athens’ ancient port. Perhaps because Greece was then building a new airport for the Olympics, it had left its harbour to rot. Signs indicating separate windows for EU and non-EU citizens meant nothing. I waited behind a Jordanian, a Dane and an Israeli in the EU queue. Most of us took more than an hour to clear passport control, then wandered the dock without anyone telling us how to find the ship. Some of us went right, others left. It took time and ingenuity to find the Nissos Kypros. My father with his years at sea would have called her a rust bucket. Praying she would not sink, I boarded and made for the bar. There, an Egyptian barman told me that the millions of drachmas I’d withdrawn at the bank machine in Patras were useless on the Nissos Kypros. The ship, he explained, accepted only Cypriot pounds.

I drank beer on deck. The BBC World Service reported that the US was preparing to attack Afghanistan. Friends called from the United States and Tuscany to question the wisdom of my journey. My only agony so far was caused by the bad muzak (is there such a thing as good muzak?) of the Nissos Kypros bar. A couple whom I had met in the passport queue joined me. Anne Marie Sorensen, and Juwal, pronounced Yuval, Levy were, I guessed, in their late twenties. A Dane, she had a degree in Arabic and Hebrew. Juwal was born in Switzerland to Israeli parents and had completed high school and military service in Israel. He was hoping to go to university, probably in Denmark. They were motorcycling from Denmark, where they lived, to his family in Israel’s Negev Desert. After visiting his family, they would fly to New Zealand and Australia. He planned to return alone to Israel to ride the motorcycle back to Denmark and join his wife there.

They were among those lucky – or blessed – married couples who go well together, relaxed, listening to each other, interested in what the other said. We talked about – what should we have called them, bombs? – the hijacked aeroplanes and mass murders in America. Every few hours the radio raised the death count. By then, it was thought to be about three thousand. We talked about Israel. The people whom Juwal seemed to detest were not the Arabs so much as fanatically religious Jews. They did not recognize his marriage to his Danish wife and accused him of, in his words, polluting the blood. Anne Marie and Juwal had Bedouin friends who sounded more sophisticated – with university degrees – than more traditional nomads I had known in the deserts of Jordan and Syria. Some were academics who had, like Juwal, married Danish women.

In the morning, the radio raised the body count in America, speculated about possible culprits and predicted global economic calamity. The Nissos Kypros docked at the island of Patmos, where I had a breakfast of cheese, olives and what the Greeks call ‘Greek’ coffee. From there, we cruised beside the Turkish shore towards Rhodes. When we arrived, I went looking for my son George.

He was waiting, as promised, in an old hotel beside a forlorn, disused mosque in the centre of the Crusaders’ fortress. Twenty-three, healthy and sunburned from a week’s sailing, he took me to dinner in a tiny place he knew. The restaurant, with no name posted anywhere, lay hidden in a tight passage amid crumbling houses. Its plump and maternal proprietress had already adopted him. She was about my age and had lived in England. My son, she said, did not eat enough. She put us at a large table that more or less blocked the alley and covered it with cold beer, lots of mezze and a bountiful platter of mixed grilled meats. George was on his summer break from studying Middle East history at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). Like me, he speculated on the impact of the attacks in America. Like his sister Julia, he had misgivings about my proposed trip. We would stop in Cyprus for a few days. If the hangings of Westerners started in the Middle East, I’d fly with him back to London and postpone my trip to Aqaba a second time.

After lunch, we toured Rhodes’ old town, where Ralph Bunche, America’s United Nations mediator, negotiated the 1949 truce that interrupted the war between Israel and Egypt and led to Israel’s subsequent truces with Jordan, Syria and Lebanon. The accords he signed at the Hôtel des Roses left 700,000 Palestinian Arabs, three-quarters of Palestine’s Arab majority, permanent refugees. Under Bunche’s agreements, the UN recognized the Israeli army’s conquests of 1948 and 1949. UN Security Council Resolution 181 of 1947 had partitioned Palestine into an Arab and a Jewish state with Jerusalem as an international city. The proposed Jewish state was 55 per cent of Palestine, but Israeli victories awarded the Jewish state 78 per cent. The Rhodes and subsequent agreements left the West Bank in the hands of King Abdallah of Jordan and allowed Egypt’s King Farouk to keep the strip around Gaza City next to Sinai. The Palestinian Arabs got nothing. With the West Bank and Gaza, Jordan and Egypt inherited hundreds of thousands of refugees cleansed from what had become the Jewish state. The Palestinian Arabs, then as subsequently, were not consulted. Israel, the Arab states, the United Nations and the United States were content to leave most of them as wards of the UN. The UN established two temporary agencies – the UN Troop Supervisory Organization that monitored the disengagement lines and the UN Relief and Works Agency that fed, housed and educated Palestinian Arab refugees. Both have been in the Middle East ever since. The UN’s pro forma Resolution 194 of 1948, renewed annually, required that Palestinian Arab ‘refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date’. No one enforced it, and the 700,000 refugees became, with their descendants and those expelled in the 1967 war, more than three million. Ralph Bunche, setting a precedent, accepted a Nobel Peace Prize for negotiations that produced – not peace – but more punishing wars.

Back on the deck of the Nissos Kypros, where the muzak blended with the engine’s rumbling, Juwal, Anne Marie, George and I discussed the Middle East to which we were sailing. Juwal told us a story about his father, Udi Levy. Udi Levy had demanded that the word ‘Jew’ be removed from his national identity card. In Israel, nationality did not mean citizenship. It meant racial origin. Udi Levy was proud to be a Jew, but he did not accept being defined as one by the state, especially when the state gave its Jewish citizens privileges it denied to Arabs. He fought through the courts and won. Juwal had inherited some of his father’s dissidence, refusing to serve in the army of occupation in the West Bank and Gaza. As with many other refuseniks, the military found a way to avoid prosecuting him. They let him serve in the navy. The sea was not occupied.

Where Juwal came from, kids made tougher decisions than ours had to. Some joined the army. Some ran away to other countries. Some went to prison rather than shoot Palestinian children, demolish houses and enforce a military occupation in which they did not believe. On the Palestinian side, youngsters threw rocks at tanks, ambushed settlers or committed suicide in order to kill other kids they believed were their enemies. Some Palestinian boys worked for the Israelis, as labourers in settlements or as police collaborators; others languished in Israeli interrogation rooms or prison cells.

Dreams on Maps

When the Nissos Kypros reached Cyprus, my friend Colin Smith met us at Limassol port. Colin lived in Nicosia. When we met first in Jerusalem, he was the Observer’s roving correspondent and I was working for ABC News in Lebanon. A few months later, we covered the independence war in Eritrea together with the photographer Don McCullin and Phil Caputo of the Chicago Tribune. A couple of weeks of hell in the desert with guerrillas who got us lost, denied us water and nearly left us for dead started our long friendship. Caputo went on to write novels, and Colin had collaborated with the journalist John Bierman on books about Orde Wingate, the British officer who more or less created the Israeli army, and on the battle of El Alamein.

That night, Colin, his wife Sylvia and their grown-up daughter Helena took us on foot to a Greek restaurant in an old house near the Green Line between Turkish and Greek Nicosia. The Aegean’s owner was a Greek Cypriot political fanatic named Vasso. Vasso, with a beard as long and black as an Orthodox archbishop’s, could have given lessons in political intransigence to Israeli settlers and Palestinian suicide bombers. His cause was Enosis, the union of Cyprus with Greece. The décor of his courtyard hostelry gave his politics away. Pride of place went to a huge wall map that showed Cyprus as part of Greece – not just politically, but physically, a few hundred miles closer than it is on the earth. The eastern Mediterranean was the region of creative map making. Syrian maps included Turkish Alexandretta in Syria and left a blank for Israel, a void that Syrian politicians called ‘the Zionist entity’. Many Israeli maps included Judaea, Samaria and Gaza in ‘Greater Israel’. Some Arab nationalists’ maps, based on those of the eighth century, showed an Arab state from Morocco to Iraq. A Kurdish map delineated Greater Kurdistan from the Mediterranean to Armenia and Iran.

When Colin introduced me as his American friend, Vasso said, ‘I am strongly anti-American … policy.’ The delayed ‘policy’ seemed to come out of consideration for the thousands who had died a few days before. It was clear he did not normally add it. He confessed that, despite his politics, he sympathized with Americans over the massacres. Perhaps the struggle between Christendom and Islam took precedence over his hatred of Henry Kissinger, who, as secretary of state in 1974, had supported Turkey’s invasion of the Cypriot Republic. Turkey was reacting to a coup attempt by the Greek Cypriot National Guard, whose leader, Nikos Sampson, had championed Vasso’s dream of Enosis. Since then the island had been sliced into Turkish and Greek halves. Vasso ran a good restaurant in a stone house whose style anyone but Vasso would have called Ottoman. The wine was rough, the food deliciously grilled. We stayed late, arguing politics with a band of Greek actors at another table and, as usual with Colin for almost thirty years, drinking too much. We walked home along the Green Line. Colin nearly led us into a Turkish checkpoint. That detour would be harmless in the morning, but at night a Turkish conscript might shoot.