Полная версия:

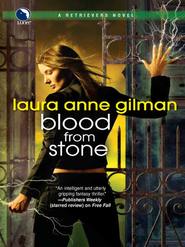

Blood from Stone

Praise for the Retrievers novels of

laura anne gilman

Staying Dead

“An entertaining, fast-paced thriller set in a world where cell phones and computers exist uneasily with magic, and a couple of engaging and highly talented rogues solve crimes while trying not to commit too many of their own.”

—Locus

Curse the Dark

“With an atmosphere reminiscent of Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code and Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose by way of Sam Spade, Gilman’s second Wren Valere adventure (after Staying Dead) features fast-paced action, wisecracking dialog and a pair of strong, appealing heroes.”

—Library Journal

Bring It On

“Ripping good urban fantasy, fast-paced and filled with an exciting blend of mystery and magic…this is a paranormal romance for those who normally avoid romance, and the entire series is worth checking out.”

—SF Site

Burning Bridges

“This fourth book in Gilman’s engaging series delivers…Wren and Sergei’s relationship, as usual, is wonderfully written. As their relationship moves in an unexpected direction, it makes perfect sense—and leaves the reader on the edge of her seat for the next book.”

—Romantic Times BOOKreviews [4 stars]

Free Fall

“An intelligent and utterly gripping fantasy thriller, by far the best of the Retrievers series to date.”

—Publishers Weekly, starred review

Laura Anne Gilman

Blood From Stone

AUTHOR NOTE

Blood from Stone was an easy book to write—and a difficult one at the same time.

Easy, because I’ve lived with these characters, their personalities and problems, for the length of six books now. We’ve been together for the long haul, and each book is like visiting with old and dear friends.

Difficult, because with this book their story comes to a (temporary) close. The Cosa Nostradamus universe continues with Hard Magic, but Wren and Sergei will be taking a short break to let Bonnie and her crew take center stage. While I’m sad to see them go, I’m thrilled that Bonnie’s getting her chance to shine. You can read a teaser for that book at the end of this one.

Meanwhile, you have Blood from Stone yet to read, wherein Wren and Sergei are faced with a new challenge—one that involves Wren’s sidekick P.B. and the fate of all demon-kind!

Enjoy!

Laura Anne Gilman

May 2009

There’s only one person this book could be dedicated to:

my editor, Mary-Theresa Hussey, who has put up with this entire

crew and their writer for six books now, and come back and

asked for more….

And maybe that’s all that we need is to meet in the middle of impossibility.

—“Mystery”

Indigo Girls

Contents

Prologue

Chapter one

Chapter two

Chapter three

Chapter four

Chapter five

Chapter six

Chapter seven

Chapter eight

Chapter nine

Chapter ten

Chapter eleven

Chapter twelve

Chapter thirteen

Chapter fourteen

Chapter fifteen

Chapter sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter eighteen

Chapter nineteen

Chapter twenty

prologue

“Why do you think you need it?”

“I…” He wants to say that he doesn’t know, but that’s already been established as a cop-out. He may not know, but there is a reason. There is always a reason. So he says what he already knows. “It feels good. The pain. But it’s not about masochism. It’s about trust.” That was true. It felt true. “The pain means that something bad is happening, but I trust that nothing will go wrong.”

“But things do. You’re damaging yourself. Every time you do it, you’re hurting yourself.”

“I didn’t…I don’t care. I still need it.” A pause, because he has always been honest in his own way. “I don’t need it. I want it. I want it enough to risk everything. And it will cost me everything. That’s why I’m here.”

“It” was current, magical energy. Talent could use it, manipulate it. To a Null like himself, it was deadly, screwing with the internal organs. Being caught in a current backlash was like being repeatedly hit with lightning bolts. Nobody in their right mind would find it a turn-on.

It wouldn’t be the first time he’d wondered if he was crazy.

“What do you what to accomplish here? Do you want to not want it?”

That was the damned thing about therapists. They ask the kinds of questions you don’t want to think about, much less answer. He shifts in the chair, his legs suddenly too long for comfort, his hands too large, his skin too tight around his frame.

“What do you want?” The voice probes again, soothing but insistent.

“I don’t know. That’s the problem.”

“Indeed.”

“I hate it when you say that. I hate everything about this.”

“Then why are you here?”

Sergei shifts again, wishing desperately for his cigarette case. He hasn’t had a cigarette in years, but right now, the feel of the thin cylinder in his fingers would be just as soothing as the hit of nicotine ever was. Because he doesn’t know why he is here, doesn’t know what he is supposed to do or say, or bring out of it.

“I don’t know.”

Except he does know. Wren. Always, ever, Wren Valere. Partner, lover, best friend…the source of his addiction, and the thing he would lose, if he couldn’t get it under control.

He just doesn’t know how to do that, without walking away from her, too.

one

In the middle of a copse of trees, bordered on one side behind her by a dry creek bed and on the other in front of her by a low stone wall covered with moss and bird shit, Wren Valere crouched, her backside an inch off the leaf-strewn ground, her palms resting on her knees, and her knees complaining about the whole situation. She was tired, sweaty and pissed-off at the universe in general and one person in particular.

“Annoying, ignorant woman,” she scolded that person, hidden inside the house on the other side of that wall. “You couldn’t have taken the kid to Boston, or Philadelphia, or somewhere semicivilized? No, you had to go all bucolic and pastoral and…leafy.” Wren reached up to pull another twig out of her braid, and wiped sweat off her forehead with the back of her hand. It was a lovely, autumn-crisp day, pale blue skies overhead, and she was sure that there were hundreds of people driving up and down the winding county road a few miles back for the sole purpose of enjoying the scarlet-and-orange display of the maples and oaks and whatever else those trees were. More power to them.

Wren Valere was not a nature girl. The leaves were pretty, and she was glad it was a nice day, but she wanted to be home, on concrete and steel, surrounded by the familiar and comforting hum of current running through the city. Home was Manhattan, where magic fed on and was fed by the torrents of electricity running in the city’s veins. A Talent like her—a current-mage, a practitioner of modern magics—had no business being out here in the woods, miles from anything more powerful than a solar powered bug-zapper.

Genevieve, you’re exaggerating, she heard her mother’s voice say, exasperated. All right, she admitted that she might be overstating things slightly. It still felt like middle-of-no-wheresville to her: too quiet, too green and too still, electrically speaking.

The thought made her reach instinctively, a mental touch stroking the core of current nestled inside her, deep in a nonexistent-to-X-rays cavity somewhere in her gut, just to make sure it was still there. Like a bank, you could overdraw and forget to refill, and even though she knew she had enough in there, it was a nervous twitch, obsessive-compulsive, to make sure, and then make sure again.

Current was similar to—but not quite identical to—the electrical energy the modern world had harnessed to do its bidding. They were, so far as anyone could determine, generated off the same sources, and appeared in the same natural and man-made situations, but with a vastly different result when channeled by their natural conductors. Metal, in the case of electricity: Talent, in the case of current.

The more abstract and technical distinctions between current and electricity were lost on most of the Cosa Nostradamus, the worldwide magical community, except those very few who made an actual study of it.

Wren wasn’t one of those few. She wasn’t an academic; she was a Retriever. She came, she stole, she went home, with no interest in the whys, so long as it worked. Although she freely admitted that the feeling of it simmering inside was nice, too. Some Talent described their internal core of magic, the power they carried with them at all times, as a pool of potent liquid, or birds flocking together, their feathers rustling with power. For her, it was a pit of serpents, thick-muscled neon beasts sliding and slithering against each other. The touch filled her with a quiet satisfaction, a sense of power resting under her skin, ready if she needed it.

Reassured, she moved forward through the trees, only to be pulled up short by something tugging on her braid, before realizing that it wasn’t an attack—or at least, not one she needed to worry about.

Reaching back, Wren removed her braid from the grasp of a branch and scowled at it, as though it alone were responsible for her bad mood. “I hate camping. I hate bugs. I hate trees.”

She didn’t really hate trees—Rorani, one of her oldest friends, was a dryad in fact, which made her an actual, honest-to-God tree hugger. Wren had never needed to go camping to know how she felt about it. She preferred luxury hotels to sleeping on the ground.

She did hate bugs, though. Wren grimaced, and reached a hand down the back of her outfit, scratching at something irritating her skin. She pulled her hand away and made a face, shaking the remains of the unidentifiable insect off her fingers. She especially hated bugs that kept trying to crawl under the fabric of her slicks to reach the bare skin underneath.

“Ugh.” She wiped her fingers on the grass. “Next job? High-rise. Climate controlled. Coffee shop on the corner.” She kept her voice low, more from habit than belief that there was anyone around to hear her. “God, I’d kill for a cup of halfway decent coffee….”

She really shouldn’t be in a bad mood at all, even with bugs and twigs. Coffee and the rest of civilization would be waiting for her when she got home, same as always. This was just a job, and it would be over soon. And money in the bank made every job better, in retrospect.

Tugging the hood of her formfitting black bodysuit over her ears, making sure that the braid was now tucked comfortably inside the fabric, Wren kept crawling forward until she reached a low hedge of some prickly-leaved bushes. Rising up to her knees, she scowled over the shrubbery at the perfectly lovely little cottage on the other side of nowhere.

All right, she told herself, enough with the griping and the moaning. Showtime.

She let herself reassess the scenario, just to get the brain in the right place. The area was on the grid. She could feel the quiet hum of electrical wires—man-made power—overhead, not far away. There wasn’t a lot, but if she suddenly had a need it was there to draw down on. Comforting. And the house wasn’t totally isolated—despite the screen of trees, a half-hour hike would bring her back to the highway, and it was probably only a few minutes’ drive from the front door to the nearest coffee joint. If, of course, you had a car.

The job had specified no traces, though, which meant that renting a car, even using one of her many fake IDs, was out. Frustrating, but manageable. The client was paying large sums for this to be a spotless, trouble-free Retrieval, and that was what The Wren would deliver. No muss, no fuss, no anything the courts could use at a later date against the client. Everything had to be perfect.

It was more than just ego at stake, that perfection, although she was always about that. This particular job had come to Sergei, her partner/business manager, not through the usual route of the Cosa Nostradamus or his art world contacts, but through a retired NYC cop now living upstate, a guy named McKierney who moonlighted as a bounty hunter. The client had gone to him originally, but this kind of grab wasn’t McKierney’s scene. He had heard about The Wren through his own contacts, and had given the client her name and Sergei’s contact number as the go-to girl for this particular job.

She didn’t get many jobs out of the urban areas, where most of the Cosa congregated. A satisfied client here, among human Nulls, could open up a whole new market for her, and there was no way she was going to give less than everything to it, even if it involved trees and bugs and crawling around in the dirt. Sergei had drummed that career advice into her head years ago: you never knew when the next client was going to be the million-dollar meal ticket.

Yeah, the job stank, on a bunch of levels. Money—and clients with money—got her into a lot of situations she didn’t enjoy. But this job had something even better than money to offer: there was absolutely no stink of magic to the Retrieval. After spending a year of their lives immersed in a literal life-and-death struggle, when what seemed like half the city suddenly set out to wipe the streets clear of anything that looked as though it might be magical, and then having to give over another nine months to the job of cleaning up the aftermath—and getting her own life back into some kind of order—Wren was more than ready for something distinctly unmagical. Even a be-damned custodial he-said-she-said, with a four-year-old kid as the prize.

That was the job she was on, right now. Mommy had grabbed the kid and run. Wren was here to Retrieve him for Daddy, who was the client.

Wren shifted on her haunches, still feeling the creepy-crawling sensation of bug legs on her skin. That was the real reason she was griping, not the green leafy buggy nature thing. Live Retrievals were a bitch. She’d only done two before, and both of them had involved adults. One she’d been able to reason with, the other she’d had Sergei along to help conk the target over the head when the reasoning didn’t work.

She steadfastly didn’t think of the third live Retrieval she had done. That had been different. That…hadn’t been her, entirely.

Hadn’t it?

Nobody had judged. Nobody had said anything after, except thank you. She had restored a dozen teenagers to their family, broken the spine of the anti-Cosa organization, the Silence. But Wren didn’t list that Retrieval in her nonexistent CV. She didn’t talk about it. She tried not to remember anything about it, the hours of cold rage and hot current spinning her out of control, making her—for the second time in her life—into a killer, however justified those deaths were, to save the lives of others. No matter that she hadn’t been entirely sane at the time.

Inanimate things were easier to Retrieve, every way up and down. Adult live retrievals were bad enough: seriously tough to stash a four-year-old in your knapsack. They tended to squirm.

And yet…the challenge was irresistible. The benefits for a job well done were deeply rewarding. So here she was.

Wren didn’t let herself think about the morality of the Retrieval, either way. If possession was nine-tenths of the law, The Wren was the other tenth. Not that she didn’t have standards about what was just or fair; she just didn’t let them get in the way of an accepted job. If something set off Sergei’s well-honed antenna for fishy, she trusted him to say no before she ever knew the offer had been made. That was his job.

“And you need to be getting on with yours already,” she muttered, annoyed at herself. Taking a deep breath, she felt her annoyance, acknowledged it, and then let it go, slipping away like water down a drain.

Shifting to rise up a little more, risking exposure, she reached into the pouch strapped to her ribs, pulling out a pair of tiny, old-fashioned binoculars. She raised the ’nocs to her eyes and looked at the target. The lens allowed her to zoom in, picking up the details that blueprints and aerial shots couldn’t give. Nothing like on-the-spot reconnaissance, no matter what the tech-types might claim.

The cottage was a build-by-numbers kit, probably prefab. Nice, though. One story, with a half attic, and windows designed to let in light without giving a direct view in. Brown wood and shingles with blue trim, and an off-white matte roof that, she had been told, was supposed to be more fuel-efficient than the traditional black ones. So, new, or at least with a newish roof. A roof, she noted, that overhung the windows just enough to allow someone with a decent amount of agility to drop down and reach those windows. Bad architect, and worse contractor, to let that get past.

Someone hadn’t considered the landscaping from a security angle, either. The cottage faced into a small lawn and a gravel road that led down to the main road, but the back was set into a copse of mature trees. The contractor had managed to build into the existing site, rather than bulldozing and replanting. Pretty. Lousy security, but pretty.

She lowered the binoculars and looked at the cottage unaided. It still looked like an invitation to larceny. Perfect. Now she just had to find a way in, and the job was halfway done. Unfortunately, the hard half was still to come.

Dropping back down behind the hedge entirely, Wren settled herself into a more comfortable crouch on the damp soil, and let herself sink into fugue state.

It used to take her the count of five-seven, when she was still in training. Now, the thought was no sooner thought than it became action. The outside world didn’t fade so much as become irrelevant; she could still see and hear and sense everything that went on around her but it was less real than the world she could “see” inside. In that world, every living thing was colored with vivid current, from the shadowy, flickering purple of the insects around her to the solid, slow-pulsing silver of the trees, and the passing bright red of something the size of a large cat, or maybe a fox. Stronger flickers up in the branches suggested that there might be piskies in the area. No other Fatae, not even the hint of a dryad or wood-mocker. Interesting. Not indicative, necessarily, but…interesting.

Everything carried current within itself; sliding into a fugue state allowed a Talent—a witch, a mage, or a wizard, if you liked the older terms—to find, access and use it more efficiently. Strong Talent—traditionally called “Pures”—could sense and use more current; weaker Talent, obviously, less.

Wren had always been strong, with little interrupting the flow of current in her veins. Last year, she had become—however temporarily—the recipient of current gifted by the Fatae, the nonhuman members of the Cosa Nostradamus. That blast had temporarily unblocked every channel in her system, kicking her from mostly Pure to too Pure. Talent bodies might be able to handle that much magic, but human brains weren’t designed for it. She had been able to work amazing things in the short term, but it had also screwed with her in ways she was still discovering.

One of those new long-term results was that, once in fugue state, she could sense the presence of current in almost every animate thing, and a few inanimate things, as well.

A nice little side effect, yeah. She could, if she had to, find a refueling station almost anywhere. Unfortunately, using fugue state now also gave her cramps that made PMS feel like a walk in the proverbial park. Everything had a price.

So don’t linger. Get it done and get out she reminded herself even as she reached out to gather as much information as she could about the structure in front of her. Just because there was no visible sign of defenses, either physical or magical, didn’t meant they weren’t there. Careless got you dead or caught, and both were bad news.

She pulled current from her core, shaping it with her will and intent until greedy tendrils of neon-colored power stretched outward, touching and tasting the air, searching for any hint of either current or electricity.

Nothing. A void stretched in front of her: no defenses, and no house, either. Nothing but trees. Impossible, if she believed what her eyes told her. Even if they had built a house without any electrical wiring whatsoever, she should have been able to sense the natural current within the wood, stone and metals, much less the flesh-and-blood entities moving within those walls.

Some Talent trusted their magical senses more than their physical ones. Wren wasn’t that arrogant, or that dumb. When the two senses disagreed, something was hinky. Either the house itself was an illusion, or something she couldn’t sense was blocking it from being found by magic. Both options were…disturbing.

Giving her Talent one last try, she stretched a tendril of current out, not toward the building, but down, sinking it deep into the soil and stone, reaching for anything that might have been laid in the foundations, deep enough to be hidden to even a directed search. Wren felt a cramp starting, low in her belly, and ignored it, extending herself even as she remained firmly grounded in her body. Sink and stretch, just a little more, just to make sure…

What the…? She touched a warmth—a hard, sharp warmth—tucked underneath the crust, deep in the bedrock where there should only have been cold earth. It spread beyond the house, covering a wider range, suggesting that the house was only secondary, protected as an afterthought. Was that what was blocking her? She pushed a little more, trying to determine the cause. Wh—

At her second touch, something shoved back at her, hard. Unprepared, the magical blow almost knocked her over, physically.

The hell? she thought, pissed off as much at being caught by surprise as at the assault itself. She touched it again with a handful of current-tendrils, not quite a shove in response, but not gentle, either.

That something in the bedrock expanded, filled with thick, hot anger and a wild swirling sense of frustration swamped her own current and tendrils. Angry, yes, and sullen, all that and a feeling of bile-ridden resentment that threatened to consume her, and something worse underneath, something darker and meaner and rising fast.

Yeeeah, outta here, she thought in near panic. Outta here now.

Dropping out of fugue state, Wren blinked a few times to let her eyesight return to normal, and then moved away from the hedge as carefully and as quickly as she could manage. A branch crackled underfoot, and she froze, and then moved backward again. Too clumsy, she was making too much noise. Damn. Her skills as a Retriever were legend, but moving invisibly through an occupied house was a different kind of ability than being able to move silently through trees and shrubs, complete with a carpeting of annoyingly crunchy leaves underfoot.

She was shaking, and sweating, and it annoyed her.

Once her nerves told her that she had gotten far enough away to feel secure, she dropped to the ground, placing her bare palms flat against the soil, letting the extra current in her system run off into the earth, grounding herself, bringing everything back into balance and soothing the restless, roiling shimmer of her core.

“Jesus wept,” she whispered, too shaken to really care if a squirrel or Piskie or too-curious wood-knocker heard her at this point. “What the hell was that?”

two