Полная версия:

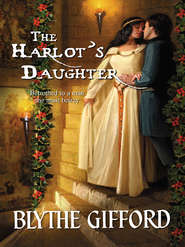

The Harlot’s Daughter

The Harlot’s Daughter

Blythe Gifford

www.millsandboon.co.uk

For my mother, a trailblazer.

And with great thanks to Pat White,

who kept me going.

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Epilogue

Author’s Afterword

Chapter One

Windsor Castle,

Yuletide, 1386

The shameless doxy dragged the rings right off his fingers before the King’s body was cold.

They used to whisper that and then look sideways at her, thinking that a ten-year-old was too young to understand they slandered her mother.

Joan had understood even then. It was all too clear the night the old King died and her mother, his mistress of thirteen years, gathered their two daughters and fled into the darkness.

Now, ten years after her father’s death, Joan stood poised to be announced at the court of a new King. Her mother hoped Joan might find a place there, even a husband.

Foolish dreams of an ageing woman.

Waiting to be announced, she peeked into the Great Hall, surprised she did not look more outdated wearing her mother’s made-over dress. It was the men’s garb, colourful and garish, that looked unfamiliar. Decked in blues and reds, gold chains and furs, they looked gaudy as flapping tournament flags.

Except for one.

Standing to the left of the throne turned away from her, he wore a simple, deep blue tunic. She could not see his face fully, but the set of his jaw and the hollow edge of his cheek said one thing: unyielding.

For a moment, she envied that strength. This was a man whose daily bread did not depend on pleasing people.

Hers did. And so did her mother’s and sister’s.

She pulled her gaze away and smoothed her velvet skirt. Please the King she must, or there would be no food in the larder by Eastertide.

As the herald entered the Hall to announce her, she heard the rustling skirts of the ladies lining the room. They whispered still.

Here she comes. The harlot’s daughter. No more shame than her mother had.

She lifted her head. It was time.

Amid the whispers, Lady Joan, twenty summers, illegitimate daughter of the late King and his notorious mistress and the most unmarriageable woman in England, stepped forward to be presented to King Richard II.

Lord Justin Lamont avoided Richard’s court whenever possible. He had braved the crowded throne room only because he had urgent news for the Duke of Gloucester.

Last month, Parliament had compelled the reckless young King to accept the oversight of a Council headed by his uncle, Gloucester. Since then, Justin had been enmeshed in the business of government. He was only beginning to uncover the mess young Richard and his intimates had made of the Treasury.

Thrust upon the throne as a boy when his grandfather died, Richard had inherited the old King’s good looks without his strength, judgement or sense. Instead of spending taxes to fight the French, he’d drained the royal purse with grants for his favourites.

When he demanded more tax money, Parliament had finally balked, installing the Council to gainsay the King’s outrageous spending.

Now, the King had put forth another of his endless lists of favours for his friends, expecting the new Council’s unquestioning approval.

He would not get it.

‘Your Grace,’ Justin said to Gloucester, ‘the King has a new list of gifts he wants to announce on Christmas Day. The Council cannot possibly approve this.’

Distracted, the Duke motioned to the door. ‘Here she comes. The doxy’s daughter.’

Justin gritted his teeth, refusing to turn. The mother’s meddling had near ruined the realm before Parliament had stepped in to save a senile King from his own foolishness. This new King needed no more misguidance. He was getting that aplenty from his current favourites. ‘What do they call her?’

‘Lady Joan of Weston,’ Gloucester answered. ‘Joan the Elder.’

Calling her a Weston was a pleasant fiction, though the old King’s mistress had passed herself off as Sir William’s wife while she bore the King’s children. ‘The Elder?’

Gloucester smirked. ‘There were two daughters. Like bitch pups. Call “Joan” and one will come running.’

Wincing at the cruelty, Justin reluctantly turned, with the rest of the court, to see whether the daughter carried the stain of her mother’s sin.

He looked, and then could not look away.

Her mother’s carnality stamped a body that swayed as if it had no bones and her raven hair carried no hint of the old King’s sun-tinged glory. ‘She looks nothing like him,’ he murmured.

Gloucester whispered back, ‘Maybe the whore simply whelped the children and called them the King’s.’

Justin shook his head. ‘She moves like royalty.’

Head high, she stared at a point above the King’s crown, walking as if the crowd adored instead of loathed her.

But then, just for a moment, she glanced around the room. Her eyes, violet, brimming with pain, met his.

They stopped his breath.

Wide-eyed, still looking at him, she did not complete her step. Tangled in her gaze, he forgot to breathe.

Then she gathered herself, lifted her skirt and approached the throne.

He shook off her spell and looked around. No one had noticed that her eyes had held his for an eternity.

She dipped before the King, head held high. Justin thought of the lad on the throne as a boy, though, at twenty, he had been King for half his life. Yet he still played at kingly ceremony, instead of grappling with the hard work of governing.

‘Lower your gaze,’ the King said to the woman before him.

A flash of fury stiffened her spine. Then, she bent her neck ever so slightly.

‘Kneel.’

She dropped gracefully to her knees as if she had practised.

Justin took a breath. Then another. Still the King did not say ‘rise’. A smothered cough in the crowd breached the silence.

Her hands hung quietly at her sides, but her fingers twitched against the folds of her deep red skirt.

He squashed a spark of sympathy. The woman’s glance had been enough to warn him. Her mother had bewitched a King. He would be on guard.

He had been deceived by a woman’s eyes once—long ago.

Joan had known the King would test her. Kneel. So she did. Her mother had taught her well. Read his needs and satisfy them. That is our only salvation. This one needed deference, that was obvious. She would give him that and whatever else he asked if he would grant them a living from the royal purse.

At least there was one thing he would not ask. The blood of the old King flowed through both their veins. She would not have to please a King as her mother had.

She heard no whispers now. Silent, the court watched as the King left her on aching knees long enough that she could have said an extra Paternoster for her mother’s sins.

Eyes lowered, she looked toward the edge of the wide-planked floor. The men’s long-toed shoes curled like a finger crooked in invitation. She stifled a smile. Men and their vanities. Apparently, they thought the longer the toes, the longer the tool.

Yet when her eyes had met those of the hard-edged man at the fringes of the crowd, she had nearly stumbled. His severe dress and implacable gaze sliced through the peacocks around the throne sharply as a blade. For that instant, she forgot everything else. Even the King.

A thoughtless mistake. She had no time for emotion. Only for necessity.

Finally, the King’s high-pitched voice called a reprieve. ‘Lady Joan, daughter of Sir William of Weston, rise and bow.’

With no one’s hand to lean on, she wobbled as she stood. Forcing her shaking knees to support her, she curtsied, then dared lift her eyes.

Tall, thin, and delicately blond, King Richard perched on the throne overlooking the hall. A golden crown graced his curls. An ermine-trimmed cloak shielded him from the draughts. She wondered whether his cheeks were clean shaven from choice or because the beard had not yet taken hold.

His slope-shouldered wife sat beside him. Her plaited brown hair hung down her back, a strange affectation for a married queen. Of course, Joan’s mother had whispered, after six years of childless marriage, she wondered how much of a wife the Queen was.

‘We hope you enjoy this festive time with us, Lady Joan,’ she said. Her eyes held a gentleness that was missing from the King’s.

Joan, silent, looked to the King for permission.

He waved his hand. ‘You may speak.’

‘Thank you, your Grace.’

He sat straighter and lifted his head. ‘Address us as Your Majesty.’

‘Forgive me, Your Majesty.’ She bowed again. A new title, then. ‘Your Grace’ had served the old King, but that was no longer adequate. This King needed more than deference. He needed exaltation.

The Queen’s soft voice soothed like that of a calm mother after a child’s tantrum. ‘I hope you will not miss Christmas at Weston Castle too much, Lady Joan.’

She suppressed a laugh. A Weston in name only, she had never even visited the family estate. It was her mother and sister she would be thinking of during the Cristes-maesse, but no word of them would be spoken aloud. ‘Your invitation honours me, Your Majesty.’

Queen Anne said, ‘Perhaps you might pen a short poem for our entertainment.’

‘Poem, Your Majesty?’

‘Not in French, only in English. If you feel capable.’

She swallowed the subtle insult. The Queen’s words denigrated not only her mother, but Joan’s ten years spent away from Windsor’s glories. Still, as a daughter of the King, she had been taught both English and French. ‘Your Majesty, if my humble verse might amuse, I would be honoured.’

The King spoke. ‘Of course you would, Lady…What was your name?’

‘Joan, Your Majesty.’

He frowned. ‘I do not like that name. Have you another?’

‘Another name, Your Majesty?’ Odd, she thought, then she remembered. The King’s mother had been called Joan. And his mother had been a bitter enemy of hers. Of course she could not be called by the name of his beloved mother. ‘Yes, Your Majesty, I do.’ It would not be the Mary or Elizabeth or Catherine he expected. ‘My mother also calls me Solay.’

‘Soleil?’ he said, with the French inflection. ‘The sun?’

‘Yes.’

‘Why would she give you such a name?’

She hesitated, fearing to speak the truth and unable to think of a way to dissemble. ‘She said I was the daughter of the sun.’

Whispers ricocheted around the floor. I was the Lady of the Sun once, her mother had said. The Sun who was King Edward.

The King dismissed her with a wave. ‘Your name matters little. You will not be here long.’

Fear twisted her stomach. She must cajole him out of anger and gain time to win his favour.

‘Your use of the name honours me,’ she said quickly, ‘as much as the honour of knowing I share the exalted day of your birth under the sign of Capricorn.’ She knew no such thing, but no one cared when she had come into the world. Even her mother was not sure of the day.

He sat straighter and peered at her. ‘You study the stars, Lady Solay?’

She knew little more of the stars than a candle maker, if the truth be told, but if the stars intrigued him, flattery and a few choice phrases should suffice. ‘Although I am but a student, I hear they say great things of Your Majesty.’

He looked at her sharply. ‘What do they say?’ he said, leaning forward.

What did he want to hear? She must tread carefully. Too much knowledge would be dangerous. ‘I have never read yours, of course, Your Majesty.’ To do so without his consent could have meant death. She thought quickly. The King’s birthday was on the twelfth day of Christmas. That should give her enough time. ‘However, with your permission, I could present a reading in honour of your birthday.’

‘It would take so long?’

She smiled and nodded. ‘To prepare a reading worthy of a King, oh, yes, Your Majesty.’

The King smiled, settling back into the throne. ‘A reading for my birthday, then.’ He turned to the tall, dark-haired man on his right. ‘Hibernia, see that she has what she needs.’

She released a breath. Now if she could only concoct a reading that would direct him to grant her mother an income for life. ‘I will do my humble best and be honoured to serve Your Majesty in any way.’

A small smile touched his lips. ‘I imprisoned the last astrologer for predicting ill omens. I shall be interested in what you say.’

She swallowed. This King was not as naïve as he looked.

Done with her, he rose, took the Queen’s hand and spoke to the Hall. ‘Come. Let there be carolling before vespers.’

Solay curtsied, muttering, ‘Thanks to Your Majesty’, like a Hail Mary and backed away.

A hand, warm, touched her shoulder.

She turned to see the same brown eyes that had made her stumble. Up close, they seemed to probe all she needed to hide.

The man was all hardness and power. A perpetual frown furrowed his brow. ‘Lady Joan, or shall I say Lady Solay?’

She slapped on a smile to hide the trembling of her lips. ‘A turn in the carolling ring? Of course.’

He did not return her smile. ‘No. A private word.’

His eyes, large, heavy lidded, turned down at the corners, as if weighed with sorrow.

Or distrust.

‘If you wish,’ she said, uneasy. As he guided her into the passageway outside the Great Hall, she turned her attention to him, ready to discover who he was, what he wanted and how she might please him.

God had blessed her with a pleasing visage. Most men were content to bask in the glow of her interest, never asking what she might think or feel.

And if they had asked, she would not have known what to say. She had forgotten.

Yet this man, silent, stared down at her as though he knew her thoughts and despised them. Behind him, the caroller’s call echoed off the rafters of the Great Hall and the singers responded in kind. She smiled, trying to lift his scowl. ‘It’s a merry group.’

No gentle curve sculpted the lips that formed an angry slash in his face. ‘They sound as if they had forgotten we might have been singing beside the French today.’

She shivered. Only God’s grace had kept the French fleet off their shores this summer. ‘Perhaps people want to forget the war for a while.’

‘They shouldn’t.’ His tone brooked no dissent. ‘Now tell me, Lady Solay, why have you come to court?’

She touched a finger to her lips, taking time to think. She must not speak without knowing whose ear listened. ‘Sir, you know who I am, but I do not even know your name. Pray, tell me.’

‘Lord Justin Lamont.’

His simple answer told her nothing she needed to know. Was he the King’s man or not? ‘Are you also a visitor at Court?’

‘I serve the Duke of Gloucester.’

She clasped her fingers in front of her so they would not shake. Gloucester had near the power of a king these days. Richard could make few moves without his uncle’s approval, a galling situation for a proud and profligate Plantagenet.

She widened her eyes, tilted her head and smiled. ‘How do you serve the Duke?’

‘I was trained at the Inns of Court.’

She struggled to keep her smile from crumbling. ‘A man of the law?’ A craven vulture who never kept his word, who would speak for you one day and against you the next, who could take away your possessions, your freedom, your very life.

‘You dislike the law, Lady Solay?’ A twist of a smile relaxed the harsh edges of his face. For the first time, she noticed a cleft in his chin, the only softness she’d seen in him.

‘Wouldn’t you, if it had done to you what it did to my mother?’ Shame, shame. Do not let the anger show. It was over and done. She must move on. She must survive.

‘It was your mother who did damage to the law.’

His bluntness shocked her. True, her mother had shared the judges’ bench on occasion, but only to insure that the King’s will was done. Most judges could not be trusted to render a verdict without an eye on their pockets.

Solay kept her brow smooth, her eyes wide and her voice low. ‘My mother served the Queen and then the King faithfully. She was ill served in the end for her faithful care.’

‘She used the law to steal untold wealth. It was the realm that was ill served.’

Most only whispered their hatred. This man spoke it aloud. She gritted her teeth. ‘You must have been ill informed. All her possessions were freely given by the King or purchased with her own funds.’

‘Ah! So you are here to get them back.’

She cleared her throat, unsettled that he suspected her plan so soon. ‘The King honoured me with an invitation. I was pleased to accept.’

‘Why would he invite you?’

Because my mother begged everyone who would still listen to ask him. ‘Who can know the mind of a King?’

‘Your mother did.’

‘A King does as he wills.’

A spark of understanding lit his eyes. ‘Parliament turned down her last petition for redress so she has sent you to beg money directly from the King.’

‘We do not beg for what is rightfully ours.’ She lowered her eyes to hide her anger. Parliament had impeached one of the King’s key advisers last autumn, then given the five Lords of the Council unwelcome oversight of the King. It was an uneasy time to appear at court. She had no friends and could afford no enemies. ‘Please, do not let me detain you. My affairs need not be your concern. You must have many friends to see.’

‘I’m not sure that anyone has many friends these days, Lady Solay. You asked about my work. Among my duties is to see that the King wastes no more money on flatterers. If you try to entice him into raiding the Exchequer on your behalf, your affairs will become my concern.’

The import of his words sank in. She risked angering a man who had power over the very purse strings she needed to loosen.

‘I only ask that you deal fairly.’ A vain hope. She had given up on justice years ago.

She stepped back, wanting to leave, but he touched her sleeve and moved closer, until she had to tip her head back to see his eyes. He was tall and lean and in the flickering torch fire, his brown hair, carelessly falling from a centre parting, glimmered with a hint of gold.

And above his head hung a kissing bough.

He looked up and then back at her, his eyes dark. She couldn’t, didn’t want to look away. His scent, cedar and ink, tantalised her.

Let them look. Make them want, her mother had warned her, but never, never want yourself. Yet this breathless ache—surely this was want.

He leaned closer, his lips hovering over hers. All she could think of was his burning eyes and the harsh rise and fall of his chest. She closed her eyes and her lips parted.

‘Do you think to sway me as your mother swayed a King, Lady Solay?’

She pushed him away, relieved the corridor was still empty, and forced her lips into a coy smile. ‘You make me forget myself.’

‘Or perhaps I help you remember who you really are.’

Her smile pinched. ‘Or who you think I am.’

‘I know who you are. You are an awkward remnant of a great King’s waning years and glory lost because of a deceitful woman.’

Gall choked her. ‘You blame my mother for the King’s decline, not caring how hard she worked to keep order when he could not tell sun from moon.’

When he did not know, or care to know, the daughter he had spawned.

‘I, Lady Solay, can tell day from night. Your mother’s tricks will not work on me.’

Then I must try some others, she thought, frantic.

What others did she know?

He had made her forget herself. She had been too blunt. Next time, she must use only honeyed words. ‘I would never try to trick you, Lord Justin. You are too wise to be fooled.’

Muttering a farewell, she turned her back and walked away from this man who lured her into anger she could ill afford.

Shaken, Justin watched her hips sway as she walked, nay, floated away. He had nearly kissed her. He had barely been able to keep his arms at his side.

He had been taken in once by a woman’s lies. Never again.

Still, it had taken every ounce of stubborn strength he could muster not to pull her into his arms and plunder her mouth.

Well, nothing magical in responding to eyes the colour of purple clouds at sunset and breasts round and soft. He would not be a man if he did not feel something.

‘There you are.’ Gloucester was at his elbow. ‘What possessed you, Lamont, to whisper secrets to the harlot’s daughter?’

Gloucester’s harsh words grated, although Justin had thought near the same. ‘Such a little difference, between one side of the blanket and the other,’ he said, turning to look at the Duke. ‘You share a father. You might call her sister.’

Gloucester scowled. ‘You are ever too outspoken.’

‘I’m just not afraid to tell the truth.’ But about this, he was. The truth was that he had no idea what possessed him to nearly take her in his arms and he did not want to dwell on the question. ‘The woman sought to tempt me as her mother did the old King.’

‘You looked as if you were about to succumb.’

‘I simply warned her that she would not be permitted to play with King Richard’s purse.’

Gloucester snorted with disgust. ‘My nephew is a sorry excuse for a ruler. The French steal my father’s land and all the boy does is read poetry and wave a little white flag to wipe his nose. As if a sleeve were not good enough.’ Gloucester sighed. ‘Now, what was it you wanted to tell me?’

Justin brought his mind back to the King’s list. ‘He wants to give the Duke of Hibernia more property.’

‘And what of my request?’

Justin shook his head.

Gloucester exploded. ‘First he gives the man a Duke’s title that none but a King’s son has ever held. Then he gives him a coat of arms adorned with crowns. Now he gives him land and leaves me at the mercy of the Exchequer? Never!’

‘I’ll tell him, your Grace. Right after vespers.’ To Justin had fallen the task of delivering bad news. He was not a man to hide the truth. Even from the King.

But he suspected that Lady Solay was. Nothing about her rang true, including her convenient birth day. As he and Gloucester returned to the hall, Justin wondered whether one of the old King’s servants might remember something of her.

If she believed she was going to tap the King’s dwindling purse with honeyed kisses, she would be sorely disappointed.

He would make sure of that.

Chapter Two

In the hour after sunset, Justin strode towards the King’s chamber, dreading this meeting. The King expected an answer on his list of grants. He wasn’t going to like the one he would hear.

But Justin would deliver it, and quickly. He had another mission to accomplish before the lighting of the Yule Log.