Полная версия:

The Glass Palace

THE GLASS PALACE

AMITAV GHOSH

Copyright

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This paperback edition 2001

Copyright © Amitav Ghosh 2000

The Author asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780006514091

Ebook Edition © JULY 2012 ISBN 9780007383283

Version: 2018-05-23

Dedication

To my father’s memory

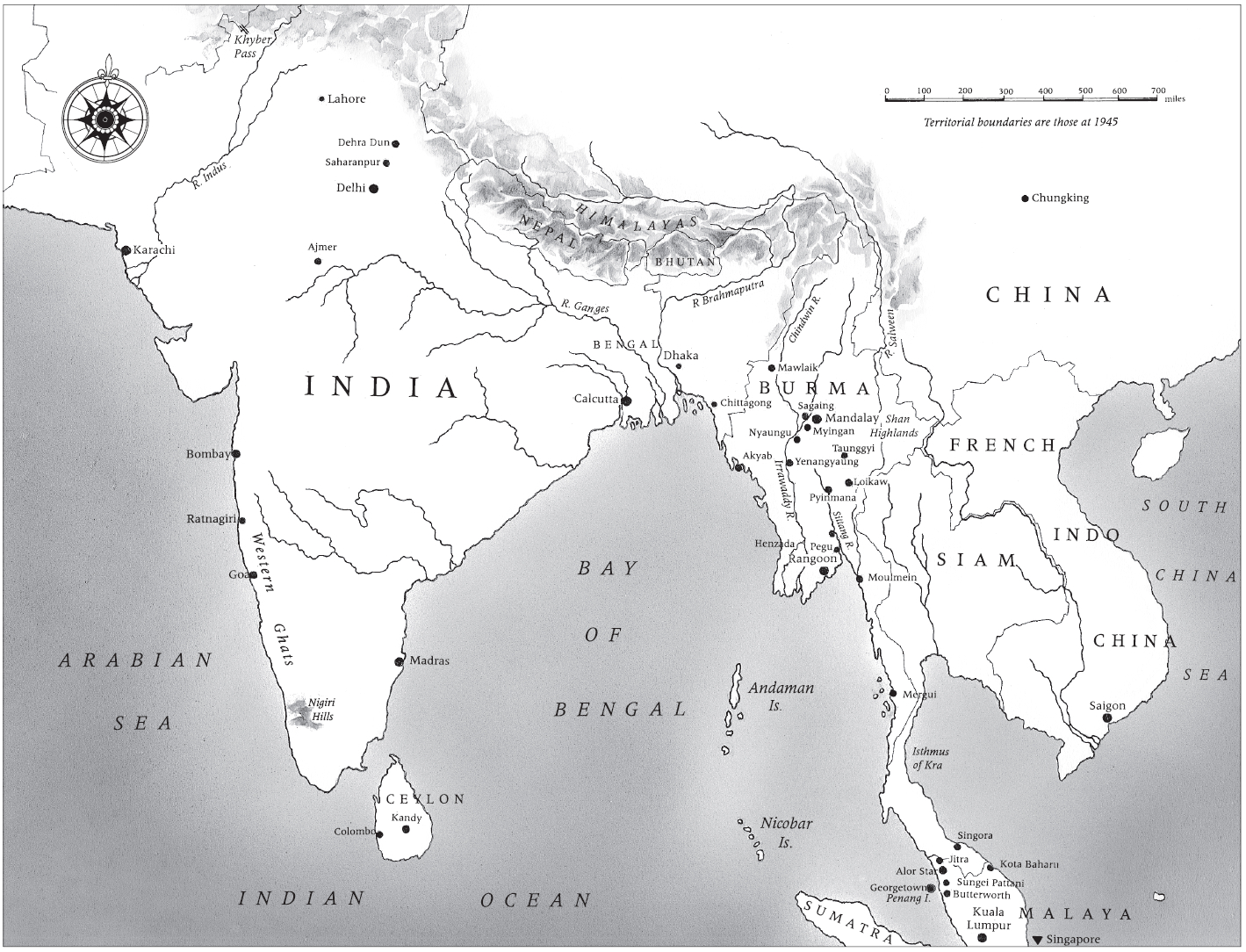

Map

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

PART ONE

Mandalay

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

PART TWO

Ratnagiri

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

PART THREE

The Money Tree

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

PART FOUR

The Wedding

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

Twenty-three

Twenty-four

PART FIVE

Morningside

Twenty-five

Twenty-six

Twenty-seven

Twenty-eight

Twenty-nine

Thirty

Thirty-one

PART SIX

The Front

Thirty-two

Thirty-three

Thirty-four

Thirty-five

Thirty-six

Thirty-seven

Thirty-eight

Thirty-nine

PART SEVEN

The Glass Palace

Forty

Forty-one

Forty-two

Forty-three

Forty-four

Forty-five

Forty-six

Forty-seven

Forty-eight

Acknowledgments

Author’s Notes

Praise

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

One

There was only one person in the food-stall who knew exactly what that sound was that was rolling in across the plain, along the silver curve of the Irrawaddy, to the western wall of Mandalay’s fort. His name was Rajkumar and he was an Indian, a boy of eleven – not an authority to be relied upon.

The noise was unfamiliar and unsettling, a distant booming followed by low, stuttering growls. At times it was like the snapping of dry twigs, sudden and unexpected. And then, abruptly, it would change to a deep rumble, shaking the food-stall and rattling its steaming pot of soup. The stall had only two benches, and they were both packed with people, sitting pressed up against each other. It was cold, the start of central Burma’s brief but chilly winter, and the sun had not risen high enough yet to burn off the damp mist that had drifted in at dawn from the river. When the first booms reached the stall there was a silence, followed by a flurry of questions and whispered answers. People looked around in bewilderment: What is it? Ba le? What can it be? And then Rajkumar’s sharp, excited voice cut through the buzz of speculation. ‘English cannon,’ he said in his fluent but heavily accented Burmese. ‘They’re shooting somewhere up the river. Heading in this direction.’

Frowns appeared on some customers’ faces as they noted that it was the serving-boy who had spoken and that he was a kalaa from across the sea – an Indian, with teeth as white as his eyes and skin the colour of polished hardwood. He was standing in the centre of the stall, holding a pile of chipped ceramic bowls. He was grinning a little sheepishly, as though embarrassed to parade his precocious knowingness.

His name meant prince, but he was anything but princely in appearance, with his oil-splashed vest, his untidily knotted longyi and his bare feet with their thick slippers of callused skin. When people asked how old he was he said fifteen, or sometimes eighteen or nineteen, for it gave him a sense of strength and power to be able to exaggerate so wildly, to pass himself off as grown and strong, in body and judgement, when he was, in fact, not much more than a child. But he could have said he was twenty and people would still have believed him, for he was a big, burly boy, taller and broader in the shoulder than many men. And because he was very dark it was hard to tell that his chin was as smooth as the palms of his hands, innocent of all but the faintest trace of fuzz.

It was chance alone that was responsible for Rajkumar’s presence in Mandalay that November morning. His boat – the sampan on which he worked as a helper and errand-boy – had been found to need repairs after sailing up the Irrawaddy from the Bay of Bengal. The boatowner had taken fright on being told that the work might take as long as a month, possibly even longer. He couldn’t afford to feed his crew that long, he’d decided: some of them would have to find other jobs. Rajkumar was told to walk to the city, a couple of miles inland. At a bazaar, opposite the west wall of the fort, he was to ask for a woman called Ma Cho. She was half-Indian and she ran a small food-stall; she might have some work for him.

And so it happened that at the age of eleven, walking into the city of Mandalay, Rajkumar saw, for the first time, a straight road. By the sides of the road there were bamboo-walled shacks and palm-thatched shanties, pats of dung and piles of refuse. But the straight course of the road’s journey was unsmudged by the clutter that flanked it: it was like a causeway, cutting across a choppy sea. Its lines led the eye right through the city, past the bright red walls of the fort to the distant pagodas of Mandalay hill, shining like a string of white bells upon the slope.

For his age, Rajkumar was well-travelled. The boat he worked on was a coastal craft that generally kept to open waters, plying the long length of shore that joined Burma to Bengal. Rajkumar had been to Chittagong and Bassein and any number of towns and villages in between. But in all his travels he had never come across thoroughfares like those in Mandalay. He was accustomed to lanes and alleys that curled endlessly around themselves so that you could never see beyond the next curve. Here was something new: a road that followed a straight, unvarying course, bringing the horizon right into the middle of habitation.

When the fort’s full immensity revealed itself, Rajkumar came to a halt in the middle of the road. The citadel was a miracle to behold, with its mile-long walls and its immense moat. The crenellated ramparts were almost three storeys high, but of a soaring lightness, red in colour, and topped by ornamented gateways with seven-tiered roofs. Long straight roads radiated outwards from the walls, forming a neat geometrical grid. So intriguing was the ordered pattern of these streets that Rajkumar wandered far afield, exploring. It was almost dark by the time he remembered why he’d been sent to the city. He made his way back to the the fort’s western wall and asked for Ma Cho.

‘Ma Cho?’

‘She has a stall where she sells food – baya-gyaw and other things. She’s half-Indian.’

‘Ah, Ma Cho.’ It made sense that this ragged-looking Indian boy was looking for Ma Cho: she often had Indian strays working at her stall. ‘There she is, the thin one.’

Ma Cho was small and harried-looking, with spirals of wiry hair hanging over her forehead, like a fringed awning. She was in her mid-thirties, more Burmese than Indian in appearance. She was busy frying vegetables, squinting at the smoking oil from the shelter of an upthrust arm. She glared at Rajkumar suspiciously: ‘What do you want?’

He had just begun to explain about the boat and the repairs and wanting a job for a few weeks, when she interrupted him. She began to shout at the top of her voice, with her eyes closed: ‘What do you think – I have jobs under my armpits, to pluck out and hand to you? Last week a boy ran away with two of my pots. Who’s to tell me you won’t do the same?’ And so on.

Rajkumar understood that this outburst was not aimed directly at him: that it had more to do with the dust, the splattering oil and the price of vegetables than with his own presence or with anything he had said. He lowered his eyes and stood there stoically, kicking the dust until she was done.

She paused, panting, and looked him over. ‘Who are your parents?’ she said at last, wiping her streaming forehead on the sleeve of her sweat-stained aingyi.

‘I don’t have any. They died.’

She thought this over, biting her lip. ‘All right. Get to work, but remember you’re not going to get much more than three meals and a place to sleep.’

He grinned. ‘That’s all I need.’

Ma Cho’s stall consisted of a couple of benches, sheltered beneath the stilts of a bamboo-walled hut. She did her cooking sitting by an open fire, perched on a small stool. Apart from fried baya-gyaw, she also served noodles and soup. It was Rajkumar’s job to carry bowls of soup and noodles to the customers. In his spare moments he cleared away the utensils, tended the fire and shredded vegetables for the soup pot. Ma Cho didn’t trust him with fish or meat and chopped them herself with a grinning short-handled da. In the evenings he did the washing-up, carrying bucketfuls of utensils over to the fort’s moat.

Between Ma Cho’s stall and the moat there lay a wide, dusty roadway that ran all the way around the fort, forming an immense square. Rajkumar had only to cross this apron of open space to get to the moat. Directly across from Ma Cho’s stall lay a bridge that led to one of the fort’s smaller entrances, the funeral gate. He had cleared a pool under the bridge by pushing away the lotus pads that covered the surface of the water. This had become his spot: it was there that he usually did his washing and bathing – under the bridge, with the wooden planks above serving as his ceiling and shelter.

On the far side of the bridge lay the walls of the fort. All that could be seen of its interior was a nine-roofed spire that ended in a glittering gilded umbrella – this was the great golden hti of Burma’s kings. Under the spire lay the throne room of the palace, where Thebaw, King of Burma, held court with his chief consort, Queen Supayalat.

Rajkumar was curious about the fort but he knew that for those such as himself its precincts were forbidden ground. ‘Have you ever been inside?’ he asked Ma Cho one day. ‘The fort, I mean?’

‘Oh yes.’ Ma Cho nodded importantly. ‘Three times, at the very least.’

‘What is it like in there?’

‘It’s very large, much larger than it looks. It’s a city in itself, with long roads and canals and gardens. First you come to the houses of officials and noblemen. And then you find yourself in front of a stockade, made of huge teakwood posts. Beyond lie the apartments of the Royal Family and their servants – hundreds and hundreds of rooms, with gilded pillars and polished floors. And right at the centre there is a vast hall that is like a great shaft of light, with shining crystal walls and mirrored ceilings. People call it the Glass Palace.’

‘Does the King ever leave the fort?’

‘Not in the last seven years. But the Queen and her maids sometimes walk along the walls. People who’ve seen them say that her maids are the most beautiful women in the land.’

‘Who are they, these maids?’

‘Young girls, orphans, many of them just children. They say that the girls are brought to the palace from the far mountains. The Queen adopts them and brings them up and they serve as her handmaids. They say that she will not trust anyone but them to wait on her and her children.’

‘When do these girls visit the gateposts?’ said Rajkumar. ‘How can one catch sight of them?’

His eyes were shining, his face full of eagerness. Ma Cho laughed at him. ‘Why, are you thinking of trying to get in there, you fool of an Indian, you coal-black kalaa? They’ll know you from a mile off and cut off your head.’

That night, lying flat on his mat, Rajkumar looked through the gap between his feet and caught sight of the gilded hti that marked the palace: it glowed like a beacon in the moonlight. No matter what Ma Cho said, he decided, he would cross the moat – before he left Mandalay, he would find a way in.

Ma Cho lived above the stall in a bamboo-walled room that was held up by stilts. A flimsy splinter-studded ladder connected the room to the stall below. Rajkumar’s nights were spent under Ma Cho’s dwelling, between the stilts, in the space that served to seat customers during the day. Ma Cho’s floor was roughly put together, from planks of wood that didn’t quite fit. When Ma Cho lit her lamp to change her clothes, Rajkumar could see her clearly through the cracks in the floor. Lying on his back, with his fingers knotted behind his head, he would look up unblinking, as she untied the aingyi that was knotted loosely round her breasts.

During the day Ma Cho was a harried and frantic termagant, racing from one job to another, shouting shrilly at everyone who came her way. But at night, with the day’s work done, a certain languor entered her movements. She would cup her breasts and air them, fanning herself with her hands; she would run her fingers slowly through the cleft of her chest, past the pout of her belly, down to her legs and thighs. Watching her from below, Rajkumar’s hand would snake slowly past the knot of his longyi, down to his groin.

One night Rajkumar woke suddenly to the sound of a rhythmic creaking in the planks above, along with moans and gasps and urgent drawings of breath. But who could be up there with her? He had seen no one going in.

The next morning, Rajkumar saw a small, bespectacled, owl-like man climbing down the ladder that led to Ma Cho’s room. The stranger was dressed in European clothes: a shirt, trousers, and a pith hat. Subjecting Rajkumar to a grave and prolonged regard, the stranger ceremoniously raised his hat. ‘How are you?’ he said. ‘Kaisa hai? Sub kuchh theek-thaak?’

Rajkumar understood the words perfectly well – they were what he might have expected an Indian to say – but his mouth still dropped open in surprise. Since coming to Mandalay he had encountered many different kinds of people, but this stranger belonged with none of them. His clothes were those of a European and he seemed to know Hindustani – and yet the cast of his face was neither that of a white man nor an Indian. He looked, in fact, to be Chinese.

Smiling at Rajkumar’s astonishment, the man doffed his hat again, before disappearing into the bazaar.

‘Who was that?’ Rajkumar said to Ma Cho when she came down the ladder.

The question evidently annoyed her and she glared at him to make it clear that she would prefer not to answer. But Rajkumar’s curiosity was aroused now, and he persisted. ‘Who was that, Ma Cho? Tell me.’

‘That is …’ Ma Cho began to speak in small, explosive bursts, as though her words were being produced by upheavals in her belly. ‘That is … my teacher … my Sayagyi.’

‘Your teacher?’

‘Yes … He teaches me … He knows about many things …’

‘What things?’

‘Never mind.’

‘Where did he learn to speak Hindustani?’

‘Abroad, but not in India … he’s from somewhere in Malaya. Malacca I think. You should ask him.’

‘What’s his name?’

‘It doesn’t matter. You will call him Saya, just as I do.’

‘Just Saya?’

‘Saya John.’ She turned on him in exasperation. ‘That’s what we all call him. If you want to know any more, ask him yourself.’

Reaching into her cold cooking fire, she drew out a handful of ash and threw it at Rajkumar. ‘Who said you could sit here talking all morning, you half-wit kalaa? Now you get busy with your work.’

There was no sign of Saya John that night or the next.

‘Ma Cho,’ said Rajkumar, ‘what’s happened to your teacher? Why hasn’t he come again?’

Ma Cho was sitting at her fire, frying baya-gyaw. Peering into the hot oil, she said shortly, ‘He’s away.’

‘Where?’

‘In the jungle …’

‘The jungle? Why?’

‘He’s a contractor. He delivers supplies to teak camps. He’s away most of the time.’ Suddenly the ladle dropped from her grasp and she buried her face in her hands.

Hesitantly Rajkumar went to her side. ‘Why are you crying, Ma Cho?’ He ran a hand over her head in an awkward gesture of sympathy. ‘Do you want to marry him?’

She reached for the folds of his frayed longyi and dabbed at her tears with the bunched cloth. ‘His wife died a year or two ago. She was Chinese, from Singapore. He has a son, a little boy. He says he’ll never marry again.’

‘Maybe he’ll change his mind.’

She pushed him away with one of her sudden gestures of exasperation. ‘You don’t understand, you thick-headed kalaa. He’s a Christian. Every time he comes to visit me, he has to go to his church next morning to pray and ask forgiveness. Do you think I would want to marry a man like that?’ She snatched her ladle off the ground and shook it at him. ‘Now you get back to work or I’ll fry your black face in hot oil …’

A few days later Saya John was back. Once again he greeted Rajkumar in his broken Hindustani: ‘Kaisa hai? Sub kuchh theek-thaak?’

Rajkumar fetched him a bowl of noodles and stood watching as he ate. ‘Saya,’ he asked at last, in Burmese, ‘how did you learn to speak an Indian language?’

Saya John looked up at him and smiled. ‘I learnt as a child,’ he said, ‘for I am, like you, an orphan, a foundling. I was brought up by Catholic priests, in a town called Malacca. These men were from everywhere – Portugal, Macao, Goa. They gave me my name – John Martins, which was not what it has become. They used to call me João, but I changed this later to John. They spoke many many languages, those priests, and from the Goans I learnt a few Indian words. When I was old enough to work I went to Singapore, where I was for a while an orderly in a military hospital. The soldiers there were mainly Indians and they asked me this very question: how is it that you, who look Chinese and carry a Christian name, can speak our language? When I told them how this had come about, they would laugh and say, you are a dhobi ka kutta – a washerman’s dog – na ghar ka na ghat ka – you don’t belong anywhere, either by the water or on land, and I’d say, yes, that is exactly what I am.’ He laughed, with an infectious hilarity, and Rajkumar joined in.

One day Saya John brought his son to the stall. The boy’s name was Matthew and he was seven, a handsome, bright-eyed child, with an air of precocious self-possession. He had just arrived from Singapore, where he lived with his mother’s family and studied at a well-known missionary school. A couple of times each year, Saya John arranged for him to come over to Burma for a holiday.

It was early evening, usually a busy time at the stall, but in honour of her visitors, Ma Cho decided to close down for the day. Drawing Rajkumar aside, she told him to take Matthew for a walk, just for an hour or so. There was a pwe on at the other end of the fort; the boy would enjoy the fairground bustle.

‘And remember –’ here her gesticulations became fiercely incoherent – ‘not a word about …’

‘Don’t worry,’ Rajkumar gave her an innocent smile. ‘I won’t say anything about your lessons.’

‘Idiot kalaa.’ Bunching her fists, she rained blows upon his back. ‘Get out – out of here.’

Rajkumar changed into his one good longyi and put on a frayed pinni vest that Ma Cho had given him. Saya John pressed a few coins into his palm. ‘Buy something – for the both of you, treat yourselves.’

On the way to the pwe, they were distracted by a peanut-seller. Matthew was hungry and he insisted that Rajkumar buy them both armloads of peanuts. They went to sit by the moat, with their feet dangling in the water, spreading the nuts around them, in their wrappers of dried leaf.

Matthew pulled a piece of paper out of his pocket. There was a picture on it – of a cart with three wire-spoked wheels, two large ones at the back and a single small one in front. Rajkumar stared at it, frowning: it appeared to be a light carriage, but there were no shafts for a horse or an ox.

‘What is it?’

‘A motorwagon.’ Matthew pointed out the details – the small internal-combustion engine, the vertical crankshaft, the horizontal flywheel. He explained that the machine could generate almost as much power as a horse, running at speeds of up to eight miles an hour. It had been unveiled that very year, 1885, in Germany, by Karl Benz.

‘One day,’ Matthew said quietly, ‘I am going to own one of these.’ His tone was not boastful and Rajkumar did not doubt him for a minute. He was hugely impressed that a child of that age could know his mind so well on such a strange subject.

Then Matthew said: ‘How did you come to be here, in Mandalay?’

‘I was working on a boat, a sampan, like those you see on the river.’

‘And where are your parents? Your family?’

‘I don’t have any.’ Rajkumar paused. ‘I lost them.’

Matthew cracked a nut between his teeth. ‘How?’

‘There was a fever, a sickness. In our town, Akyab, many people died.’

‘But you lived?’