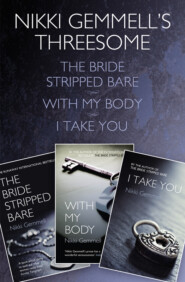

скачать книгу бесплатно

the great necessity of life is continued ceaseless change

A resolution, in mid-August. You have to move beyond this mewly time, all whingy and wrong, you have to haul yourself out. A resolution that some of the momentous issues in a relationship can in the end only be ignored if you want the relationship to survive, they can’t be worked through and tossed out. Which is why, perhaps, some people in long-term partnerships have learnt to to live with what they don’t like. To reclaim the calm. You’ve seen it in marriages that’ve weathered infidelity, have seen them contract into a tightness in old age. Do you want the relationship to survive?

It’s easier to stay than to go.

You can’t bear the thought of parties again and singles columns and intimate dinners that don’t work, of always trying to find a way to fill up a Friday night. And you were meant to be trying for a baby soon. Cole wants to be a father some day. When you found him it was like a candle to a cave’s dark and to throw it all away after you’ve got to this point, you just can’t. You’ve had the most satisfying relationship of your life with him: you’re sure the glow of companionship can come back.

Cole wants the marriage to last. Everything is denied. He doesn’t want to bail out.

You don’t want Theo to win. Sometimes you fear this consideration drowns out everything else. You can beat her with this; you can’t recall beating her at anything.

So, a resolution.

You will live with the silences between Cole and you now. For you’ve stopped the talk, both of you, you’re away in your separate rooms: he in his study, you in the bedroom, too much. At least there’s no sex and you’re relieved at that, for the memory of it has now distilled to two things: when he didn’t come it was frustrating and when he did it was messy, often over your stomach and face, like a dog at a post claiming ownership.

So many ways to live like a prisoner.

But a resolution, to find a way back into a happy life. Although God knows when the fury will soften from you.

You concentrate for the moment on making the flat very beautiful, very spare and pale, like the inside of a white balloon. To your taste, for compromise has been lost. You’ve never dared impose your will so much. The builders come to know a woman who’s never been allowed out before, especially with Cole, a woman stroppy, shorttempered, blunt.

And the flat, the beautiful flat, fit for a spread in Elle, is as silent as a skull when you enter it.

An emptiness rules at its core, a rottenness, a silence when one of you retires to bed without saying goodnight, when you eat together without conversation, when the phone’s passed wordlessly to the other. An emptiness when every night you lie in the double bed, restlessly awake, astounded at how closely hate can nudge against love, can wind around it sinuously like a cat. An emptiness when you realise that the loneliest you’ve ever been is within a marriage, as a wife.

Lesson 34 (#ulink_497c4eed-620d-51b0-ae95-283f6b250b55)

provide yourself with a good stock of well-made underlinen

The café in Soho. The Friday before the August Bank Holiday. Hot, festively so. A man is at the table beside you, reading a newspaper, The Times. You notice the nape of his neck: how odd to be attracted to someone just by a glance at their neck. The hair’s black, like the night-time deep in the country.

You’re outside on the pavement. A water main has burst nearby and water’s spreading lazily across the street. No one seems bothered, yet. Two men and a woman shout and laugh into the water and kick it about, they’re in their twenties, they shouldn’t be doing this. They’re oblivious to their audience and soon drenched.

You smile. Your Evening Standard is folded into your bag, you’ll finish it on the tube – God, rush hour, you’ve left it too late, you’ll be standing all the way. You’ve left it too late because you don’t want to be in the flat by yourself, in the silence like a skull. You hate the emptiness when Cole’s there and yet when he isn’t, too, when he’s deliberately out; it’s like nothing, now, is quite right in your life. You stand, ready to step into the stream of commuters with their faces anxious for the cloistering of home, and a car careers round the corner and carves through the water, veering away from the trio, and a fan of water arcs up: you’re hit. You’re stricken, can’t move, your mind blanks as if someone has told you a joke and you’re meant to get it quick.

You look across to the man next to you. He, too, is wet. You blurt a laugh; here at last is the joke. So does he.

You need some help, you say.

So do you.

You look down. Your white cotton dress is triumphantly wet in a huge patch at the front, it clings like a piece of recalcitrant silk slicked about a tree. You throw back your head and grimace: oh God. And then a man’s jacket is wrapped round your shoulders, a man’s leading you back to the table, he’s holding you in a way that only a husband should hold you: with ownership.

It is, of course, your man with the beautiful nape.

Lesson 35 (#ulink_2a50755c-8361-52e3-ae86-e94a8b8fb57a)

hooks and eyes

Everything is changed.

Gabriel Bonilla, that is his name. You repeat it; the sound is all mealy in your mouth. You smile in apology at that. You must wait until your dress has dried to decency; it may take some time and this Gabriel Bonilla asks if you need to get home straight away – no, it’s all right, there’s nothing to go home to – and you laugh, too loud, and as it comes out it’s as if something within you has cracked.

Well, hello.

So there you are, an hour or two in that greasy spoon of a café and you’re both talking about everything and nothing, voices tumbling over the top of each other, learning lives.

Shaking free.

You’d never talk with this freedom, this lightness, if you were unattached. Being married gives you a bloom of certainty, a confidence. But it doesn’t stop the blushing. Gabriel Bonilla blushes too, just like you, fully, completely, ridiculously and you dare to think it means something. You’re hesitant to ask about a partner and a family, you want to know, must know, but fear the effort of asking will reveal too much, that you’ll redden once again. Like after the water splash when you realised he’d seen your body so vulnerably, too many things, the thighs too fat and the nipples through your bra, God, all of it, and your hand flies to your mouth at the recollection but he drops his eyes as if he doesn’t want to intrude, as if he’s opened a door by mistake to your thoughts.

There’s something fascinating about this man sitting before you in his summer-weight suit. You can’t quite put your finger on it but it’s something decent, old-fashioned, polite. Wrong for this world, for this cram of sex shops and neon lights where a girl languid by a doorway has a junky’s spots. This Gabriel Bonilla shouldn’t be here. He’s from another time, another place; the type of person who wouldn’t expect a woman to be driving a car if there was a man in it. There’s his Spanish name and yet fluent English – my mother is English, my father Spanish – and again there’s your laugh, bursting out; ah ha, so that explains it.

What do you do, you ask.

Guess.

You lean forward, cup your chin in your palm: a teacher, doctor, spy?

I’m an actor, he says.

You sit back. Retract, just a touch. You don’t know any actors, you’re not sure you want to.

I don’t recognise you. Should I?

No, no, he chuckles. No one does, any more. I was famous once, for about a week, in my late teens. I did a dreadful soap – and he holds up his hand at your question, he’s not going to divulge – and then two Hollywood films that bombed, and I haven’t done much ever since. I now live in terror of appearing on one of those ‘Where Are They Now?’ shows.

You laugh. You’ve always been distrustful of actors, have suspected that they’ve never really muddied their paws in the mess of life, they’ve lived it second-hand. This is unfair but you’re suddenly brisk. How on earth do you live, you ask.

Voice-overs. Ads. Foreign video rights. The occasional guest role. And I was sensible when I was young. I bought a flat.

What happens in between? How do you fill up your days?

Let me see, I sleep until one p.m. Have a Scotch for breakfast. Do a line of coke. You both laugh. No, no, I go to the gym and do classes as the Actors Centre, go to casting, that type of thing. Read a lot, travel a lot, row, go to the movies, drink too much tea.

You can’t grasp a life like this, none of your peers lives as loosely any more. This Gabriel Bonilla answers your questions as if he’s answered them a thousand times before and he couldn’t care less. The lack of concern over welfare and career path and what he’s doing with his life is intriguing, silly, odd. He strikes you as a man who’s not hungry for anything, he has a flat and enough money to get by; there’s no need to grasp or to rush. It’s not unattractive, this lightness. Then he says he’s working on a script about something else he’s addicted to and you lean forward: what, come on, tell me?

Bullfighting.

The gulp of a laugh. You stuff the little girl down, sit on the lid of her box.

Bullfighting?

He’s laughing too, his father was a matador but he was never much of a success because he wasn’t suicidal enough, he liked his life too much. His father only ever fought in provincial rings but he’s got an idea for a film, he’s told his family he’s finally embarking on a proper life and he’s burying himself in London’s wonderful libraries, the world’s best, and he’s up to his ears in research. He’s writing in them, too, because he’d go mad if he didn’t get out. You examine his hands, long and lean, like a priest’s, you take them in yours and he tells you the strength in a matador’s wrist is what they rely on to make their mark and your hands slip under his and try to encircle them like two rowlocks for oars and you feel their weight, clamp them, soft.

Are your father’s anything like these, you ask.

Absolutely. The spitting image. I also have his cough. And his laugh.

But they’re so thin, you tease, they couldn’t kill a bull!

It’s not about aggression or force. Oh dios mio, you have so much to learn, and his head is bowing down to his palms still in yours.

How did it get to this, so suddenly, so quickly? You sit back. Look at him. The lower lip puffy, pillowed, ripe for splitting. The long, black lashes like a child’s. The tallness in the seat, the slight self-consciousness to it, as if he was mocked, perhaps, at school. The body kept in shape. There’s a beauty to him, to his shyness, his decency, you’ve never been with a man who has a beauty to his body, it’s never mattered, you’ve never cared about that enough. You imagine this Gabriel Bonilla naked, your palm on his chest, reading the span of it and the beating heart, and you cross your legs and squeeze your thighs and smile like a ten-year-old who’s just been caught with the last of her grandmother’s chocolates.

I’ll take you to a bullfight some day, he says. You’ll love it, I promise.

You feel the heat in your cheeks, you try to still it down, you see the heat in his too. You recognise his shyness for you’ve always been shy yourself. You rarely see shyness in a man, it’s always disguised as arrogance, abruptness, aloofness. You’re too alike, this Gabriel and you. You recognise it in the way he doesn’t sit quite comfortably in the world, can’t quite keep up. A jobbing actor, still, and he’s OK with that. He smiles, right into your eyes, you’re distracted and all your questions are suddenly wiped out. He turns the conversation back upon yourself, interviews you as if he’s trying to extract the marrow of your life: your marriage, flat, family, job, colleagues, boss. You answer openly, easily, talk slips out smooth, it’s all ripe with a dangerous kind of readiness, a lightness is singing within you.

But you tell yourself you will never spoil it all by sleeping with him, will never have the connection stained by that. You don’t want sudden awkwardness, don’t want sour sleeper’s breath in the morning or unflushed toilets and smoker’s breath or farts. It took you a year to fart when Cole was in an adjoining room, two to fart in the same room. You sometimes bite the inside of your mouth so furiously that blood’s drawn and the rabbity working of your lips is a private, peculiar thing that no one but Cole ever sees. You cut your toenails in front of him, wear underwear that’s falling apart, defecate, piss. You open yourself to your husband in a way you don’t for anyone else but perhaps he knows too much: all the magic’s been lost.

Cole.

You used to talk like this with him once, when you were lovers just starting out. You don’t want Gabriel Bonilla ever to be disappointed in you, to drift before anything’s begun. So the situation will be preserved just exactly as it is, like a secret document that’s tucked deep into a pocket of your wallet, always hidden, always close, that you can take out and dream about at will, a safe’s combination, a treasure map, a prisoner’s plan of escape.

Gabriel takes out a fountain pen that opens with a click as agreeable as a lipstick. He scribbles down a number on the back of the bill. A man hasn’t given you his number for so long. What does it mean, what comes next, is he playing with you, is it a game? And when your fingers brush you draw back, too quick.

He knows you’re married. He says he’d like to meet Cole. Which throws you.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: