Полная версия:

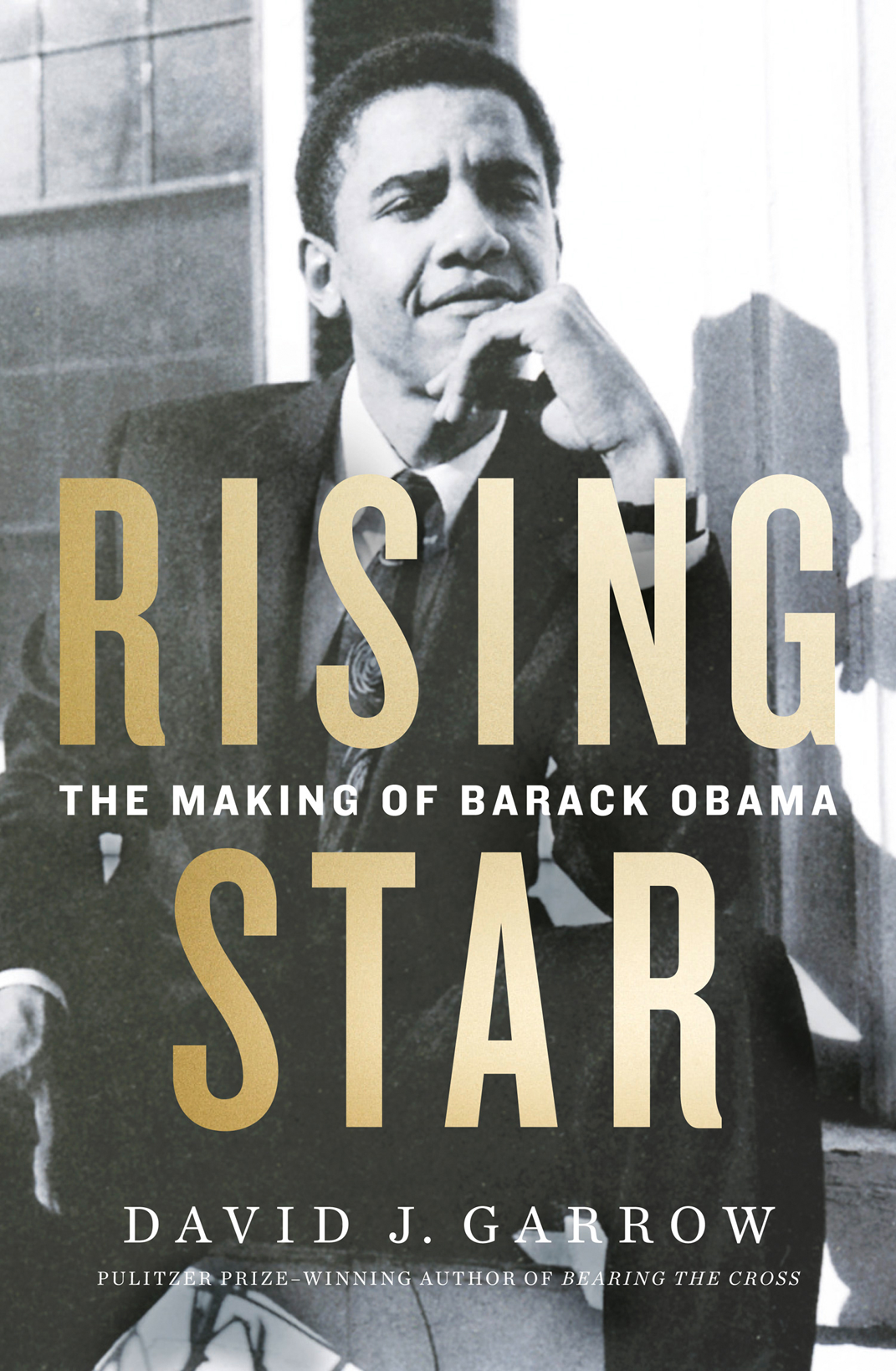

Rising Star: The Making of Barack Obama

COPYRIGHT

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017

Copyright © 2017 by David J. Garrow

David J. Garrow asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Cover photograph © 1990 John Goodman

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008229375

Ebook Edition © May 2017 ISBN: 9780008229382

Version: 2018-05-24

For Darleen, who endured

Praise for Rising Star:

‘Phenomenal . . . one of the most impressive and important books of the year. It’s a masterwork of historical and journalistic research, Robert Caro-like in its exhaustiveness, and easily the most authoritative account of Obama’s pre-presidential life we’ve seen or are likely ever to see. It’s also a terrific read’

Politico

‘Revealing . . . Probing . . . [Garrow] tells us how Obama lived, and explores the calculations he made in the decades leading up to his winning the presidency’

Washington Post

‘Impressive . . . [A] deeply reported work of biography . . . Garrow made the inspired decision to open the book on the economically ravaged South Side of Chicago in 1980 – five years before Obama showed up as a novice community organizer – thus giving us a sidewalk-level view of the joblessness, environmental degradation and failing schools that formed day-to-day reality. We see right away what our hero is up against in his altruistic quest to “create change” . . . The depth of detail allows the reader to see familiar parts of this story with fresh eyes’

New York Times Book Review

‘[Contains] intriguing insight into the growing pains of a 20-something who would go on to become the leader of the free world’

Time

‘A tour de force . . . An epic triumph of personal and political biography’

New York Journal of Books

‘The authoritative biography of Barack Obama’s pre-presidential years . . . Illuminating . . . Impressively researched . . . Readers will be richly rewarded’

Library Journal

‘A convincing and exceptionally detailed portrait . . . Political history buffs will be fascinated’

Publishers Weekly

‘Garrow is a demon for research . . . Eminently solid . . . Consistently readable – an impressive work’

Kirkus Reviews

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

THE END OF THE WORLD AS THEY KNEW IT: CHICAGO’S FAR SOUTH SIDE

MARCH 1980–JULY 1985

Chapter Two A PLACE IN THE WORLD: HONOLULU, SEATTLE, HONOLULU, JAKARTA, AND HONOLULU AUGUST 1961–SEPTEMBER 1979

Chapter Three SEARCHING FOR HOME: EAGLE ROCK, MANHATTAN, BROOKLYN, AND HERMITAGE, PA SEPTEMBER 1979–JULY 1985

Chapter Four TRANSFORMATION AND IDENTITY: ROSELAND, HYDE PARK, AND KENYA AUGUST 1985–AUGUST 1988

Chapter Five EMERGENCE AND ACHIEVEMENT: HARVARD LAW SCHOOL SEPTEMBER 1988–MAY 1991

Chapter Six BUILDING A FUTURE: CHICAGO JUNE 1991–AUGUST 1995

Chapter Seven INTO THE ARENA: CHICAGO AND SPRINGFIELD SEPTEMBER 1995–SEPTEMBER 1999

Chapter Eight FAILURE AND RECOVERY: CHICAGO AND SPRINGFIELD OCTOBER 1999–JANUARY 2003

Chapter Nine CALCULATION, COINCIDENCE, CORONATION: ILLINOIS AND BOSTON JANUARY 2003–NOVEMBER 2004

Chapter Ten DISAPPOINTMENT AND DESTINY: THE U.S. SENATE NOVEMBER 2004–FEBRUARY 2007

Epilogue THE PRESIDENT DID NOT ATTEND, AS HE WAS GOLFING

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by David J. Garrow

About the Publisher

Chapter One

THE END OF THE WORLD AS THEY KNEW IT

CHICAGO’S FAR SOUTH SIDE

MARCH 1980–JULY 1985

Frank Lumpkin never forgot the first phone call that afternoon. Although he was off work that Friday with a broken foot, he had stopped by the pay office at Wisconsin Steel, where he’d labored for more than thirty years, to pick up checks totaling $8,084.57, money he was due in back vacation pay. He still had thirteen weeks of vacation coming, accumulated over five years, and he was about to take a long-planned trip to Africa. But March 28—“Black Friday,” as it would be called—was about to become absolutely unforgettable.

Wisconsin Steel’s hulking metal sheds stretched south and a bit eastward from the intersection of Torrence Avenue and East 106th Street in a neighborhood that most residents called Irondale, even if Chicago city maps labeled it South Deering. William Deering was a long-forgotten industrialist who had cofounded International Harvester Company in 1902; Wisconsin’s oldest corporate ancestor, Brown’s Mill, dated from 1875 and had been South Chicago’s first steel plant. Six years later, Andrew Carnegie opened a larger mill just north from where the Calumet River flowed into Lake Michigan, and by the dawn of the twentieth century the southwestern crescent of that lakeshore, stretching from the Calumet eastward across the Indiana state line to Gary and Burns Harbor, had become the most dense concentration of steel mills in the world.

Steelmaking was dangerous and strenuous work, as Frank Lumpkin well knew, but steelworkers had significant freedoms. “There were no time clocks, and they could come out for lunch,” a nearby barber recounted. “The workers figured that they could get their hair cut on company time because it grows on company time.”

By 1980 the region’s mills had sustained generation after generation of working-class families whose breadwinners didn’t need to graduate high school to get jobs that paid three times what college graduates could earn as public school teachers.

Frank and his wife Bea had raised four children during their thirty-one years of marriage, and they had just moved to South Shore, a middle-class neighborhood a bit northwest of where Carnegie’s mill—now United States Steel’s huge South Works—employed almost three times the 3,450 men who worked at Wisconsin. South Shore was a comfortable area for an interracial couple—Frank was black, Bea white—and tolerant too of a couple who had spent many years as dedicated members of the Communist Party USA. Frank’s fellow workers at Wisconsin—black, white, and Hispanic—didn’t view him as a radical, just an outgoing man who had worked his way up through the odd series of job titles a steel mill offered: chipper, scarfer, millwright.

A little after 3:00 P.M. that Friday, Frank limped across Torrence Avenue to the Progressive Steel Workers (PSW) union hall, just north of 107th Street. The PSW was a so-called “independent” union, not part of the United Steelworkers of America or any labor federation, but it was actually no more “independent” than it was “progressive.” Its first president, William Reilly, was a Wisconsin steelworker, but he left his union post to become chief labor spokesman for International Harvester, Wisconsin Steel’s corporate owner. PSW’s current president, forty-three-year-old Leonard “Tony” Roque, had been in office since 1973, and he had engineered an almost 50 percent increase in union dues, increased his own salary by thousands of dollars, and was overseeing a $150,000 expansion of the union hall. Roque was widely seen as nothing more than a flunky for the political king of South Chicago, 10th Ward alderman Edward R. “Fast Eddie” Vrdolyak, whose law firm received an annual retainer of $30,000 from the PSW and whose election campaigns the union also contributed to. Vrdolyak was a graduate of the University of Chicago’s highly prestigious law school, but some acquaintances remembered him more for the charge of attempted murder that had been filed against him, and then dropped, during his law school years.

The phone call Frank would always remember came when he was speaking with union vice president Steve Plesha at about 3:30 P.M. The message was abrupt: Wisconsin Steel was closing, the workers were being sent home, and the gates were being locked.

“He looked at me and I looked at him because I couldn’t believe it. I had just been there twenty minutes ago,” Frank recalled a decade later. What’s more, just the night before PSW had held a meeting where both Roque and Ronald K. Linde, board chairman of Wisconsin Steel’s new owner, Envirodyne Industries, had reassured some fifteen hundred members that reports about Wisconsin possibly closing were incorrect.

But the 3:30 P.M. phone call should have been less surprising than it was. Three weeks earlier, Crain’s Chicago Business—in fairness, a publication not often read by South Chicago steelworkers—had reported that Wisconsin faced “imminent bankruptcy” because its former corporate owner, International Harvester, which still bought some 40 percent of its steel from Wisconsin for use in Harvester’s farm equipment, was increasingly crippled by an ongoing United Auto Workers strike that had begun on November 1, 1979. Ironically, November 1 had also been the date when Wisconsin’s new owner, Envirodyne Industries, secured a package of loans, guaranteed by the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Economic Development Administration (EDA), to modernize its plant.

International Harvester had begun trying to sell Wisconsin in 1975, and for good reason: in 1976, Wisconsin lost $4.6 million, bringing its cumulative losses since 1970 to $77 million. By early 1977 Harvester was in serious discussions with Envirodyne, a tiny enterprise boasting just a dozen employees that focused on acquiring larger companies through stock swaps. Envirodyne had no experience in the steel industry and badly needed cash to cover an existing bank loan, but Harvester was willing to accept $50 million in notes, secured primarily by the two iron ore mines in upper Michigan, one ore ship, and coal properties in Kentucky that Wisconsin Steel also owned. More crucially, Chase Manhattan Bank was willing to provide $15 million in cash to Envirodyne. The Chicago Tribune labeled the purchase “a minnow trying to swallow a whale,” but nonetheless the sale closed on July 31, 1977, and Wisconsin’s hefty ongoing annual losses continued: $32 million on revenues of $236 million in the twelve months ending in September 1979. Thanks to EDA’s loan guarantees, six insurance companies provided $75 million, and Chase Manhattan ponied up another $15 million for current operating expenses.

The Crain’s story went on to say that “without a strong infusion of working capital,” beyond the 1979 loans, “Wisconsin’s collapse is unavoidable,” and on March 27, the Chicago Tribune’s widely respected business editor, Richard Longworth, reported that the second $15 million from Chase had been expended and that the federal EDA would support additional money for Wisconsin only if International Harvester would advance Wisconsin new funds too.

Harvester, which had recently sustained losses of $225 million during the first quarter of its 1979–80 fiscal year, worried that Wisconsin’s iron and coal mine assets were vulnerable to potential seizure by external creditors. Thus, earlier on March 28, Harvester foreclosed on those properties and the ore ship. But Harvester had failed to consult with Chase Manhattan before acting, and, according to Wisconsin plant manager George J. Harper, several hours later, Chase “impounded all our inventories and stopped all our shipments. At that point, we were literally dead,” Harper explained. “We had to start telling the workers that we were shut down.”

As one employee recounted, “We got no warning of this closing at all. I was loading boxes and the foreman came up and just told me to go home. I figured they’d run into some kind of problem with the trucks.” As Harper remembered, “We just dumped them in the street with nothing to show for what they had done…. It was anything but honorable and anything but diplomatic…. It makes you feel sick inside.”

Harper and the workers also didn’t know that Chase had frozen Wisconsin’s bank accounts. By 5:00 P.M., the foremen were instructed to tell the men on their shifts not to come back to work. Frank had returned home by that time, and his foreman telephoned him there. “Lumpkin,” he said, “don’t expect to come back to work. It looks bad.” By early Saturday morning, the news had spread to all of the workers and their families. One woman remembers being a fourteen-year-old girl when her father worked at Wisconsin. She never forgot her mother waking her on Saturday morning to tell her what had happened: “They called the ore boat back,” with the coast guard radioing it to return to South Chicago. “It was a crucial moment of rupture,” she explained, when the “widespread belief in future prosperity for oneself and one’s family” and the stability that flowed from that assumption was first called into question. Wisconsin’s closing “would tear through a fabric that had sustained generations” and portended “the collapse of the world as I had known it in Southeast Chicago.” For her dad, the mill’s demise “upended the world as my father knew it.”1

By midday on Monday, March 31, a sense of trauma, crisis, and fear had spread across the Southeast Side as people gradually realized that all of Friday’s paychecks were now worthless. Both of Envirodyne’s Wisconsin holding companies had filed for bankruptcy. One lawyer involved told Richard Longworth, “I pleaded with Chase to at least take care of those checks that bounced. Chase said they couldn’t see any legal responsibility. I told them there’s more than a legal responsibility involved here,” but that was rejected.

Scores of other businesses—industrial suppliers closely tied to Wisconsin Steel and retail establishments patronized by Wisconsin workers—immediately began to suffer their own financial consequences. By Wednesday, April 2, the Daily Calumet was reporting that more than a thousand workers at Chicago Slag & Ballast and the Chicago West Pullman & Southern Railroad, both of which had serviced Wisconsin, had also lost their jobs. The Daily Cal’s editorial page predicted “a chain reaction within the community” as “unemployment will spread forth from the plant,” and warned its readers to grasp “the all-too-real possibility” that Wisconsin “might never reopen.” If so, “in a short time, the life and breath of the community will cease to exist, and the neighborhood will be as dead as Wisconsin Steel.”

Each day the news grew worse. Before the week was out, the Daily Cal was reporting a total of “nearly 7,000 ‘ripple effect’ layoffs” by employers whose businesses had been tied to Wisconsin. The federal bankruptcy court authorized the EDA to spend up to $1 million to purchase the coal that was necessary to avoid shutting down the coke ovens—which once cooled become unstable and are impossible to restart—but as Easter weekend began, former Wisconsin workers complained that there was a two-week lag in unemployment checks, that food stamp applications were being rejected if children did not have Social Security numbers, and that Wisconsin wouldn’t let them into the plant to get their personal tools and work shoes. “All I feel now is hatred,” one worker told John Wasik, the Daily Cal reporter who was chronicling the debacle. South Chicago Savings Bank announced a three-month moratorium for Wisconsin borrowers with outstanding loans, and offered new emergency loans to the former workers too. The Daily Cal warned that “the longer the plant sits idle, the greater are the chances it will never reopen…. At stake is more than dollars and cents, more than jobs and employment … there are people at stake.”2

One voice that remained utterly silent even as the crisis moved into its third week was PSW president Tony Roque. But on Wednesday, April 16, about thirty men went first to the Chicago office of the federal National Labor Relations Board, and then to the Illinois State Department of Labor to complain about the PSW’s utter passivity, only to be told they should file claims in bankrupty court. Their efforts made the front page of the next day’s Daily Cal, and the story concluded by telling interested workers to call Frank Lumpkin at home. Roque responded immediately by sending letters to every member announcing a general meeting on Sunday, April 27—in the ballroom of the mammoth Chicago Hilton hotel, in the downtown “Loop,” more than fifteen miles north of South Deering.

The PSW’s Hilton meeting generated angry jibes—“Why have they rented the Hilton when their members can’t even buy food?” one wife asked the Tribune’s Richard Longworth—but when testimony in the federal bankruptcy case revealed that workers’ compensation coverage for the skeleton crew manning the coke ovens and blast furnace had ended on April 1, the PSW struck Wisconsin, pulling those workers from the plant. Only the EDA’s willingness to pay the $35,000 a week in natural gas costs prevented the coke ovens from going cold.3

As Wisconsin’s final death rattle was sounding, two progressive Chicago clergymen—Father Tom Joyce, a Claretian priest who directed the Claretians’ Peace and Justice Committee, and Dick Poethig, director of the Presbyterian Church’s Institute on the Church in Urban Industrial Society, decided to attend a mid-May gathering at St. Thomas More College in Covington, Kentucky, a “National Conference on Religion and Labor.” One of the featured speakers was Presbyterian minister Rev. Chuck Rawlings, who talked about his recent experience as principal organizer of the Ecumenical Coalition of the Mahoning Valley (ECMV), in northeastern Ohio.

As they listened to Rawlings, Tom Joyce and Dick Poethig could tell how similar the effects of the closing of Wisconsin were to what had occurred near Youngstown, Ohio, three years earlier. They also recognized that it had been clergymen, not union leaders, business interests, or elected officials, who had led the local community’s response.

On September 19, 1977, the Lykes Corporation announced the closing of Campbell Works, with a loss of more than forty-one hundred jobs. When Chuck Rawlings, who worked for the Church and Society department of the Episcopal Diocese of Ohio, heard of the closing, he called Episcopal bishop John H. Burt, who in turn phoned James W. Malone, the Roman Catholic bishop of Youngstown. An interfaith breakfast was convened, and Rawlings circulated a memorandum calling for church leaders to confront the steel crisis. In the meantime, Youngstown attorney Staughton Lynd contacted the Washington-based National Center for Economic Alternatives (NCEA), whose codirectors, Gar Alperovitz and Jeff Faux, believed the shutdown called for an infusion of investment capital from the federal government, which would require an “unusual political mobilization” featuring “a dramatic local and national moral campaign.” In a New York Times op-ed essay, Alperovitz and Faux called for a Tennessee Valley Authority–style “development corporation” with “mixed community and employee ownership” to oversee such a federal investment.

Rawlings’s band of Ohio bishops and pastors called themselves the Ecumenical Coalition of the Mahoning Valley (ECMV), and they convened a “Steel Crisis Conference,” at which Alperovitz was the featured speaker. Out of that came “A Religious Response to the Mahoning Valley Steel Crisis,” which was signed by more than two hundred clergy members. In this pastoral letter, the clergymen echoed Alperovitz in declaring that “this is not in any sense a purely economic problem.” They were “convinced that corporations have social and moral responsibilities,” and said they were “seriously exploring the possibility of community and/or worker ownership” of a reopened Campbell Works.

U.S. Steel chairman Edgar Speer condemned their efforts as “nothing short of a Communist takeover,” but ECMV, taking advantage of $335,000 in federal support from the Department of Housing and Urban Development, commissioned Alperovitz to undertake a six-month study to determine if Campbell could be reopened. National newspapers like the Times and the Washington Post covered the effort, especially once Alperovitz announced a preliminary finding that about $500 million would allow Campbell to reopen with about half of its prior workforce. But White House aides to President Jimmy Carter would support only $100 million and quietly asked Harvard Business School professor Richard S. Rosenbloom to evaluate Alperovitz’s analysis while postponing any decision until after the November 1978 midterm elections.

In March 1979, the White House notified the ECMV that their proposal had been rejected. Chuck Rawlings thought he and his colleagues had been “naive” to expect federal help, especially when Youngstown parishioners had remained far more silent than their pastors, but when Tom Joyce and Dick Poethig spoke with Rawlings after his presentation at the May 1980 conference about Wisconsin’s demise, his advice was decisive—“Go back and organize!”—and Tom and Dick agreed to do just that.4

Joyce knew even before he returned to Chicago that the first person he would contact was Leo Mahon. Fifty-four years old at the time of Tom’s call, Mahon had been pastor of St. Victor Roman Catholic Church in Calumet City, the first suburb just south of Chicago’s southeastern city limits, since 1975. Mahon had been ordained a priest of the Chicago archdiocese in 1951. Early on, he worked with Puerto Rican parishioners and learned Spanish while also rubbing shoulders with a young community organizer named Nicholas von Hoffman and von Hoffman’s well-known mentor, Saul Alinsky, the father of community organizing. Within a few years, Mahon became head of the archdiocese’s Committee for the Spanish Speaking, which planned to start a mission in Panama. Archbishop Albert Cardinal Meyer, whom Leo adored, chose Mahon to lead it, and in early 1963 Leo left for Panama, where he spent the next twelve years.

The San Miguelito mission flourished under Leo’s leadership, but government officials took a dim view of his pastoral defense of human rights, and pliable Catholic leaders in Panama twice put Leo on trial for heresy. After Cardinal Meyer died, in early 1965, the Vatican named St. Louis native John Patrick Cody as his successor, and Cody was far less supportive of Leo’s work. When Leo returned from Panama to Chicago in 1975, Cody, perhaps out of fear of Mahon’s possible radicalism, refused to take advantage of his Spanish and Latin American expertise and instead “exiled him” to Calumet City.