Полная версия:

The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and The Moon of Gomrath

COPYRIGHT

This ebook bundle edition published by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2015

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is

www.harpercollinschildrensbooks.co.uk

The Weirdstone of Brisingamen Text © Alan Garner 1960 The Moon of Gomrath Text © Alan Garner 1963

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2015 Cover art © Nik Keevil

Alan Garner asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of the work.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBNs:

9780007539062 (The Weirdstone of Brisingamen), 9780007539048 (The Moon of Gomrath)

Ebook edition © SEPTEMBER 2015 ISBN 9780008164386

Version 2015-08-20

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

The Weirdstone Of Brisingamen

The Moon of Gomrath

Keep Reading

About the Publisher

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

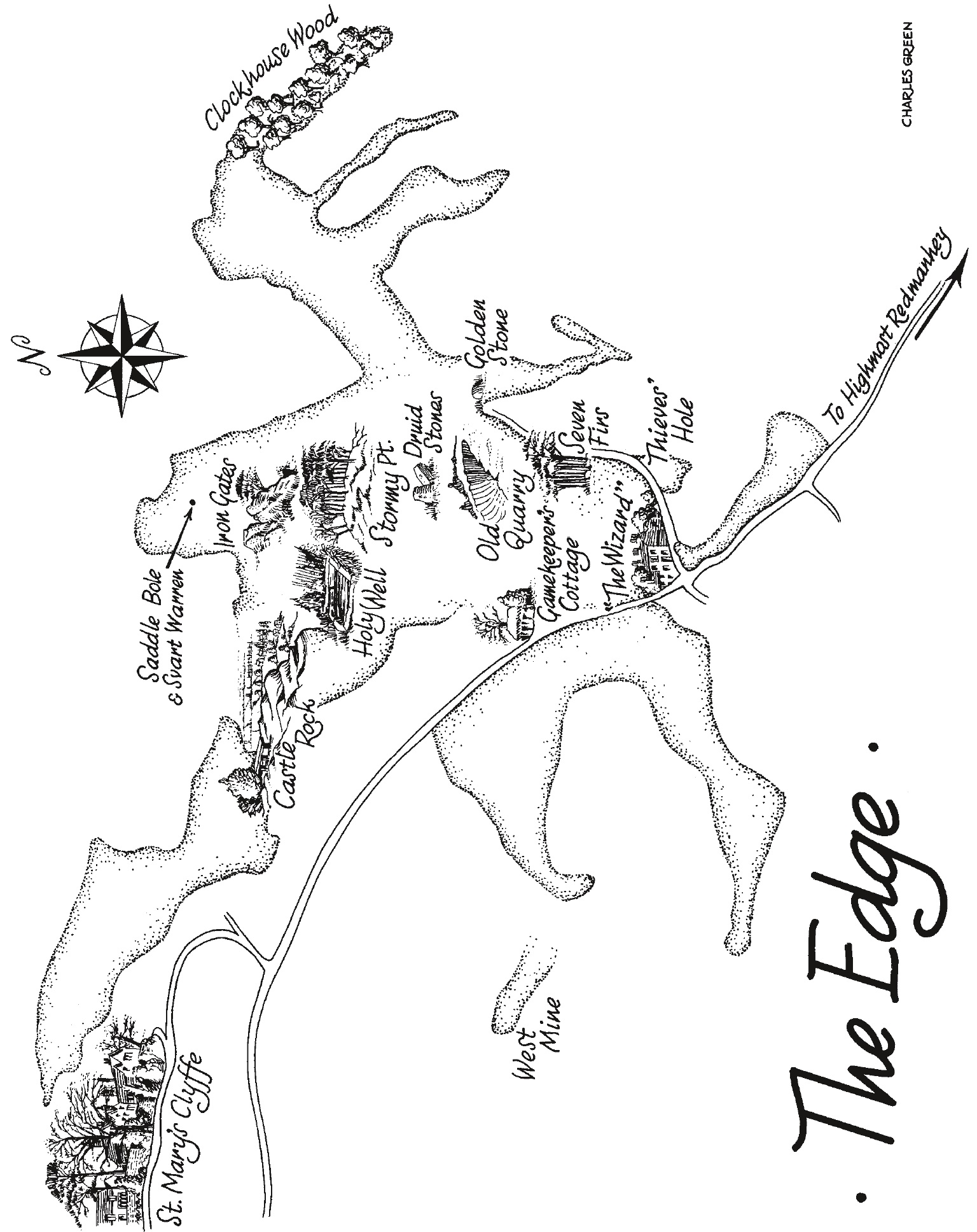

Map

Epigraph

The Legend of Alderley

PART ONE

1. Highmost Redmanhey

2. The Edge

3. Maggot-breed of Ymir

4. The Fundindelve

5. Miching Mallecho

6. A Ring of Stones

7. Fenodyree

PART TWO

8. Mist over Llyn-dhu

9. St Mary’s Clyffe

10. Plankshaft

11. Prince of the Huldrafolk

12. In the Cave of the Svartmoot

13. “Where No Svart Will Ever Tread”

14. The Earldelving

15. A Stromkarl Sings

16. The Wood of Radnor

17. Mara

18. Angharad Goldenhand

19. Gaberlunzie

20. Shuttlingslow

21. The Headless Cross

MAP

In every prayer I offer up, Alderley, and all belonging to it, will be ever a living thought in my heart.

REV. EDWARD STANLEY: 1837

THE LEGEND OF ALDERLEY

At dawn one still October day in the long ago of the world, across the hill of Alderley, a farmer from Mobberley was riding to Macclesfield fair.

The morning was dull, but mild; light mists bedimmed his way; the woods were hushed; the day promised fine. The farmer was in good spirits, and he let his horse, a milk-white mare, set her own pace, for he wanted her to arrive fresh for the market. A rich man would walk back to Mobberley that night.

So, his mind in the town while he was yet on the hill, the farmer drew near to the place known as Thieves’ Hole. And there the horse stood still and would answer to neither spur nor rein. The spur and rein she understood, and her master’s stern command, but the eyes that held her were stronger than all of these.

In the middle of the path, where surely there had been no one, was an old man, tall, with long hair and beard. “You go to sell this mare,” he said. “I come here to buy. What is your price?”

But the farmer wished to sell only at the market, where he would have a choice of many offers, so he rudely bade the stranger quit the path and let him through, for if he stayed longer he would be late to the fair.

“Then go your way,” said the old man. “None will buy. And I shall await you here at sunset.”

The next moment he was gone, and the farmer could not tell how or where.

The day was warm, and the tavern cool, and all who saw the mare agreed that she was a splendid animal, the pride of Cheshire, a queen among horses; and everyone said that there was no finer beast in the town. But no one offered to buy. A sour-eyed farmer rode out of Macclesfield at the end of the day.

At Thieves’ Hole the mare stopped: the stranger was there.

Thinking any price was now better than none, the farmer agreed to sell. “How much will you give?” he said.

“Enough. Now come with me.”

By Seven Firs and Goldenstone they went, to Stormy Point and Saddlebole. And they halted before a great rock embedded in the hillside. The old man lifted his staff and lightly touched the rock, and it split with the noise of thunder.

At this, the farmer toppled from his plunging horse and, on his knees, begged the other to have mercy on him and let him go his way unharmed. The horse should stay; he did not want her. Only spare his life, that was enough.

The wizard, for such he was, commanded the farmer to rise. “I promise you safe conduct,” he said. “Do not be afraid; for living wonders you shall see here.”

Beyond the rock stood a pair of iron gates. These the wizard opened, and took the farmer and his horse down a narrow tunnel deep into the hill. A light, subdued but beautiful, marked their way. The passage ended, and they stepped into a cave, and there a wondrous sight met the farmer’s eyes – a hundred and forty knights in silver armour, and by the side of all but one a milk-white mare.

“Here they lie in enchanted sleep,” said the wizard, “until the day will come – and come it will – when England shall be in direst peril, and England’s mothers weep. Then out from the hill these must ride and, in a battle thrice lost, thrice won, upon the plain, drive the enemy into the sea.”

The farmer, dumb with awe, turned with the wizard into a further cavern, and here mounds of gold and silver and precious stones lay strewn along the ground.

“Take what you can carry in payment for the horse.”

And when the farmer had crammed his pockets (ample as his lands!), his shirt, and his fists with jewels, the wizard hurried him up the long tunnel and thrust him out of the gates. The farmer stumbled, the thunder rolled, he looked, and there was only the rock above him. He was alone on the hill, near Stormy Point. The broad full moon was up, and it was night.

And although in later years he tried to find the place, neither he nor any after him ever saw the iron gates again. Nell Beck swore she saw them once, but she was said to be mad, and when she died they buried her under a hollow bank near Brindlow wood in the field that bears her name to this day.

CHAPTER 1

HIGHMOST REDMANHEY

The guard knocked on the door of the compartment as he went past. “Wilmslow fifteen minutes!”

“Thank you!” shouted Colin.

Susan began to clear away the debris of the journey – apple cores, orange peel, food wrappings, magazines, while Colin pulled down their luggage from the rack. And within three minutes they were both poised on the edge of their seats, case in hand and mackintosh over one arm, caught, like every traveller before or since, in that limbo of journey’s end, when there is nothing to do and no time to relax. Those last miles were the longest of all.

The platform of Wilmslow station was thick with people, and more spilled off the train, but Colin and Susan had no difficulty in recognising Gowther Mossock among those waiting. As the tide of passengers broke round him and surged through the gates, leaving the children lonely at the far end of the platform, he waved his hand and came striding towards them. He was an oak of a man: not over tall, but solid as a crag, and barrelled with flesh, bone, and muscle. His face was round and polished; blue eyes crinkled to the humour of his mouth. A tweed jacket strained across his back, and his legs, curved like the timbers of an old house, were clad in breeches, which tucked into thick woollen stockings just above the swelling calves. A felt hat, old and formless, was on his head, and hobnailed boots struck sparks from the platform as he walked.

“Hallo! I’m thinking you mun be Colin and Susan.” His voice was gusty and high-pitched, yet mellow, like an autumn gale.

“That’s right,” said Colin. “And are you Mr Mossock?”

“I am – but we’ll have none of your ‘Mr Mossock’, if you please. Gowther’s my name. Now come on, let’s be having you. Bess is getting us some supper, and we’re not home yet.”

He picked up their cases, and they made their way down the steps to the station yard, where there stood a green farm-cart with high red wheels, and between the shafts was a white horse, with shaggy mane and fetlock.

“Eh up, Scamp!” said Gowther as he heaved the cases into the back of the cart. A brindled lurcher, which had been asleep on a rug, stood and eyed the children warily while they climbed to the seat. Gowther took his place between them, and away they drove under the station bridge on the last stage of their travels.

They soon left the village behind and were riding down a tree-bordered lane between fields. They talked of this and that, and the children were gradually accepted by Scamp, who came and thrust his head on to the seat between Susan and Gowther. Then, “What on earth’s that?” said Colin.

They had just rounded a corner: before them, rising abruptly out of the fields a mile away, was a long-backed hill. It was high, and sombre, and black. On the extreme right-hand flank, outlined against the sky, were the towers and spires of big houses showing above the trees, which covered much of the hill like a blanket.

“Yon’s th’Edge,” said Gowther. “Six hundred feet high and three mile long. You’ll have some grand times theer, I con tell you. Folks think as how Cheshire’s flat as a poncake, and so it is for the most part, but no wheer we live!”

Nearer they came to the Edge, until it towered above them, then they turned to the right along a road which kept to the foot of the hill. On one side lay the fields, and on the other the steep slopes. The trees came right down to the road, tall beeches which seemed to be whispering to each other in the breeze.

“It’s a bit creepy, isn’t it?” said Susan.

“Ay, theer’s some as reckons it is, but you munner always listen to what folks say.

“We’re getting close to Alderley village now, sithee: we’ve not come the shortest way, but I dunner care much for the main road, with its clatter and smoke, nor does Prince here. We shanner be going reet into the village; you’ll see more of yon when we do our shopping of a Friday. Now here’s wheer we come to a bit of steep.”

They were at a crossroad. Gowther swung the cart round to the left, and they began to climb. On either side were the walled gardens of the houses that covered the western slope of the Edge. It was very steep, but the horse plodded along until, quite suddenly, the road levelled out, and Prince snorted and quickened his pace.

“He knows his supper’s waiting on him, dunner thee, lad?”

They were on top of the Edge now, and through gaps in the trees they caught occasional glimpses of lights twinkling on the plain far below. Then they turned down a narrow lane which ran over hills and hollows and brought them, at the last light of day, to a small farmhouse lodged in a fold of the Edge. It was built round a framework of black oak, with white plaster showing between the gnarled beams: there were diamond-patterned, lamp-yellow windows and a stone flagged roof: the whole building seemed to be a natural part of the hillside, as if it had grown there. This was the end of the children’s journey: Highmost Redmanhey, where a Mossock had farmed for three centuries and more.

“Hurry on in,” said Gowther. “Bess’ll be waiting supper for us. I’m just going to give Prince his oats.”

Bess Mossock, before her marriage, had been nurse to the children’s mother; and although it was all of twelve years since their last meeting they still wrote to each other from time to time and sent gifts at Christmas. So it was to Bess that their mother had turned when she had been called to join her husband abroad for six months, and Bess, ever the nurse, had been happy to offer what help she could. “And it’ll do this owd farmhouse a world of good to have a couple of childer brighten it up for a few months.”

She greeted the children warmly, and after asking how their parents were, she took them upstairs and showed them their rooms.

When Gowther came in they all sat round the table in the broad, low-ceilinged kitchen were Bess served up a monstrous Cheshire pie. The heavy meal, on top of the strain of travelling, could have only one effect, and before long Colin and Susan were falling asleep on their chairs. So they said good night and went upstairs to bed, each carrying a candle, for there was no electricity at Highmost Redmanhey.

“Gosh, I’m tired!”

“Oh, me too!”

“This looks all right, doesn’t it?”

“Mm.”

“Glad we came now, aren’t you?”

“Ye-es …”

CHAPTER 2

THE EDGE

“If you like,” said Gowther at breakfast, “we’ve time for a stroll round before Sam comes, then we’ll have to get in that last load of hay while the weather holds, for we could have thunder today as easy as not.”

Sam Harlbutt, a lean young man of twenty-four, was Gowther’s labourer, and a craftsman with a pitchfork. That morning he lifted three times as much as Colin and Susan combined, and with a quarter of the effort. By eleven o’clock the stack was complete, and they lay in its shade and drank rough cider out of an earthenware jar.

Later, at the end of the midday meal, Gowther asked the children if they had any plans for the afternoon.

“Well,” said Colin, “if it’s all right with you, we thought we’d like to go in the wood and see what there is there.”

“Good idea! Sam and I are going to mend the pig-cote wall, and it inner a big job. You go and enjoy yourselves. But when you’re up th’Edge sees you dunner venture down ony caves you might find, and keep an eye open for holes in the ground. Yon place is riddled with tunnels and shafts from the owd copper mines. If you went down theer and got lost that’d be the end of you, for even if you missed falling down a hole you’d wander about in the dark until you upped and died.”

“Thanks for telling us,” said Colin. “We’ll be careful.”

“Tea’s at five o’clock,” said Bess.

“And think on you keep away from them mine-holes!” Gowther called after them as they went out of the gate.

It was strange to find an inn there on that road. Its white walls and stone roof had nestled into the woods for centuries, isolated, with no other house in sight: a village inn, without a village. Colin and Susan came to it after a mile and a half of dust and wet tar in the heat of the day. It was named The Wizard, and above the door was fixed a painted sign which held the children’s attention. The painting showed a man, dressed like a monk, with long white hair and beard: behind him a figure in old-fashioned peasant garb struggled with the reins of a white horse which was rearing on its hind legs. In the background were trees.

“I wonder what all that means,” said Susan. “Remember to ask Gowther – he’s bound to know.”

They left the shimmering road for the green wood, and The Wizard was soon lost behind them as they walked among fir and pine, oak, ash, and silver birch, along tracks through bracken, and across sleek hummocks of grass. There was no end to the peace and beauty. And then, abruptly, they came upon a stretch of rock and sand from which the heat vibrated as if from an oven. To the north, the Cheshire plain spread before them like a green and yellow patchwork quilt dotted with toy farms and houses. Here the Edge dropped steeply for several hundred feet, while away to their right the country rose in folds and wrinkles until it joined the bulk of the Pennines, which loomed eight miles away through the haze.

The children stood for some minutes, held by the splendour of the view. Then Susan, noticing something closer to hand, said, “Look here! This must be one of the mines.”

Almost at their feet a narrow trench sloped into the rock.

“Come on,” said Colin, “there’s no harm in going down a little way – just as far as the daylight reaches.”

Gingerly they walked down the trench, and were rather disappointed to find that it ended in a small cave, shaped roughly like a discus, and full of cold, damp air. There were no tunnels or shafts: the only thing of note was a round hole in the roof, about a yard across, which was blocked by an oblong stone.

“Huh!” said Colin. “There’s nothing dangerous about this, anyway.”

All through the afternoon Colin and Susan roamed up and down the wooded hillside and along the valleys of the Edge, sometimes going where only the tall beech stood, and in such places all was still. On the ground lay dead leaves, nothing more: no grass or bracken grew; winter seemed to linger there among the grey, green beeches. When the children came out of such a wood it was like coming into a garden from a musty cellar.

In their wanderings they saw many caves and openings in the hill, but they never explored further than the limits of daylight.

Just as they were about to turn for home after a climb from the foot of the Edge, the children came upon a stone trough into which water was dripping from an overhanging cliff, and harmigh in the rock was carved the face of a bearded man, and underneath was engraved:

DRINK OF THIS

AND TAKE THY FILL FOR THE WATER FALLS BY THE WIZHARDS WILL

“The wizard again!” said Susan. “We really must find out from Gowther what all this is about. Let’s go straight home now and ask him. It’s probably nearly tea-time, anyway.”

They were within a hundred yards of the farm when a car overtook them and pulled up sharply. The driver, a woman, got out and stood waiting for the children. She looked about forty-five years old, was powerfully built (“fat” was the word Susan used to describe her), and her head rested firmly on her shoulders without appearing to have much of a neck at all. Two lines ran from either side of her nose to the corners of her wide, thin-lipped mouth, and her eyes were rather too small for her broad head. Strangely enough, her legs were thin and spindly, so that in outline she resembled a well-fed sparrow, but again that was Susan’s description.

All this Colin and Susan took in as they approached the car, while the driver eyed them up and down more obviously.

“Is this the road to Macclesfield?” she said when the children came up to her.

“I’m afraid I don’t know,” said Colin. “We’ve only just come to stay here.”

“Oh? Then you’ll want a lift. Jump in!”

“Thanks,” said Colin, “but we’re living at this next farm.”

“Get into the back.”

“No, really. It’s only a few yards.”

“Get in!”

“But we …”

The woman’s eyes glinted and the colour rose in her cheeks.

“You – will – get – into – the back!”

“Honestly, it’s not worth the bother! We’d only hold you up.”

The woman drew breath through her teeth. Her eyes rolled upwards and the lids came down until only an unpleasant white line showed; and then she began to whisper to herself.

Colin felt most uncomfortable. They could not just walk off and leave this peculiar woman in the middle of the road, yet her manner was so embarrassing that he wanted to hurry away, to disassociate himself from her strangeness.

“Omptator,” said the woman.

“I … beg your pardon.”

“Lapidator.”

“I’m sorry …”

“Somniator.”

“Are you …?”

“Qui libertar opera facitis …”

“I’m not much good at Latin …”

Colin wanted to run now. She must be mad. He could not cope. His brow was damp with sweat, and pins and needles were taking all awareness out of his body.

Then, close at hand, a dog barked loudly. The woman gave a suppressed cry of rage and spun round. The tension broke; and Colin saw that his fingers were round the handle of the car door, and the door was half-open.

“Howd thy noise, Scamp,” said Gowther sharply.

He was crossing the road opposite the farm gate, and Scamp stood a little way up the hill nearer the car, snarling nastily.

“Come on! Heel!”

Scamp slunk unwillingly back towards Gowther, who waved to the children and pointed to the house to show that tea was ready.

“Th – that’s Mr Mossock,” said Colin. “He’ll be able to tell you the way to Macclesfield.”

“No doubt!” snapped the woman. And, without another word, she threw herself into the car, and drove away.

“Well!” said Colin. “What was all that about? She must be off her head! I thought she was having a fit! What do you think was up with her?”

Susan made no comment. She gave a wan smile and shrugged her shoulders, but it was not until Colin and she were at the farm gate that she spoke.

“I don’t know,” she said. “It may be the heat, or because we’ve walked so far, but all the time you were talking to her I thought I was going to faint. But what’s so strange is that my Tear has gone all misty.”

Susan was fond of her Tear. It was a small piece of crystal, shaped like a raindrop, and had been given to her by her mother, who had had it mounted in a socket fastened to a silver chain bracelet which Susan always wore. It was a flawless stone, but, when she was very young, Susan had discovered that if she held it in a certain way, so that it caught the light just … so, she could see, deep in the heart of the crystal, miles away, or so it seemed, a twisting column of blue fire, always moving, never ending, alive, and very beautiful.

Bess Mossock clapped her hands in delight when she saw the Tear on Susan’s wrist. “Oh, if it inner the Bridestone! And after all these years!”

Susan was mystified, but Bess went on to explain that “yon pretty dewdrop” had been given to her by her mother, who had had it from her mother, and so on, till its origin and the meaning of the name had become lost among the distant generations. She had given it to the children’s mother because “it always used to catch the childer’s eyes, and thy mother were no exception!”