Полная версия:

The Owl Service

Books by Alan Garner

A BAG OF MOONSHINE

BONELAND

ELIDOR

RED SHIFT

THE LAD OF THE GAD

THE MOON OF GOMRATH

THE OWL SERVICE

THE STONE BOOK QUARTET

THE WEIRDSTONE OF BRISINGAMEN

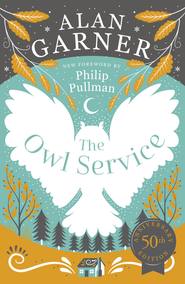

First published in Great Britain by William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1967

This edition published by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2017

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins website address is:

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Text copyright © Alan Garner 1967

Introduction copyright © Philip Pullman 2017

Decorations from the original plates by Griselda Greaves

The author acknowledges with thanks the use of the following copyright material:

The Bread of Truth by R. S. Thomas (Rupert Hart-Davis);

The Mabinogion: translated by Gwyn Jones and Thomas Jones (J. M. Dent & Sons); The Radio Times, The British Broadcasting Corporation

Cover design by studiohelen.co.uk

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007127894

Ebook Edition © 2017 ISBN: 9780007539055

Version: 2019-09-20

Praise

“Garner writes books that really matter, books driven by powerful forces within himself, our history, our language, our mythology, our world.”

David Almond

“Alan Garner is indisputably the great originator, the most important British writer of fantasy since Tolkien, and in many respects better than Tolkien, because deeper and more truthful. His work is where human emotion and mythic resonance, sexuality and geology, modernity and memory and craftsmanship meet and cross-fertilise. Any country except Britain would have long ago recognised his importance, and celebrated it with postage stamps and statues and street-names. But that’s the way with us: our greatest prophets go unnoticed by the politicians and the owners of media empires. I salute him with the most heartfelt respect and admiration.”

Philip Pullman

“Alan Garner’s fiction is something special. Garner’s fantasies were smart and challenging, based in the here and the now, in which real English places emerged from the shadows of folklore, and in which people found themselves walking, living and battling their way through the dreams and patterns of myth.”

Neil Gaiman

“The power and range of Alan Garner’s astounding talent has grown with every book he’s written.”

Susan Cooper

“Remarkable … a rare imaginative feat, and the taste it leaves is haunting.”

Observer

“In his earlier novels, The Weirdstone of Brisingamen, The Moon of Gomrath and Elidor, Garner used the successful formula of the spilling of the twilight world of ancient legend into the present day. Here he uses the formula again, with an added depth, and even more compulsive terror-haunted beauty.”

Financial Times

For Cinna

Epigraph

—The owls are restless.

People have died here,

Good men for bad reasons,

Better forgotten.—

R. S. Thomas

I will build my love a tower

By the clear crystal fountain,

And on it I will build

All the flowers of the mountain.

Traditional

Possessive parents rarely live long enough

to see the fruits of their selfishness.

Radio Times (15.9.65)

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Books by Alan Garner

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

Epigraph

Author’s Note

Introduction

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Postscript

Keep Reading

About the Author

About the Publisher

AUTHOR’S NOTE

I am indebted to Betty Greaves, who saw the pattern; to Professor Gwyn Jones and Professor Thomas Jones, for permission to use copyright material in the text; and to Dafydd Rees Cilwern, for his patience.

A. G

INTRODUCTION

When this book was first published, in 1967, I was an undergraduate at Oxford reading English, and I remember the sensation it caused – not among the academics, for whom children’s literature was an area of no interest whatsoever, but among those of us who had arrived at university with our heads already harbouring an unhealthy fascination with hobbits and elves and so on. Tolkien was all the rage, but we weren’t allowed to take an academic interest in that sort of thing because fantasy was as un-literary, as looked down on, as an enthusiasm for books that children read. The fantasy fans had already read and enjoyed the three earlier books by Alan Garner, The Weirdstone of Brisingamen (1960), The Moon of Gomrath (1963) and Elidor (1965), but The Owl Service was something new, and tougher, and truer than anything we’d yet seen.

Like the earlier books, and unlike The Lord of the Rings, The Owl Service is set in our world, the “real” world as we call it. The fantastical elements irrupt into everyday life: the realistic settings and characters experience and are altered by their encounters with the mythical or the other-worldly. This way of writing a story is sometimes known as “low fantasy”, in contrast to the “high fantasy” of the Tolkien sort, where everything is made up. I think it’s a useful distinction, and I vastly prefer the low to the high.

What distinguishes The Owl Service from its predecessors, and from pretty well anything else published for children until then, is something uncompromising in the telling. We have to keep our wits about us as we read: everything we need is there, and nothing we don’t need. A great deal of the text consists of dialogue, which is sharp and tense and brilliantly economical. As a way of revealing character, Garner’s dialogue is unsurpassed: we can almost see the patronising, unperceptive, well-intentioned and severely limited Clive, the nervy, quick-witted, imaginative, generous, rebellious Gwyn. Clive’s relationship with his stepdaughter, Alison, could hardly be better revealed than through his own words:

“You’re looking a bit peaky this morning,” said Clive. “Sure you’re OK? Mustn’t overdo things, you know. Not good for a young lady.”

The tension in the family situation is made even more vivid by the setting. Garner is exceptionally sensitive to the atmosphere of places, and the Welsh valley where he conceived the story, and where the TV version was filmed, is a powerful and oppressive character in its own right. I have driven past that valley many times, and never without feeling glad to have left it behind. Setting and people, both living and mythical, combine in this wonderful novel to produce an effect unlike anything else in fiction. Is it a children’s book? Of course it is, and of course it’s not only for children. Nowadays, I’m very glad to say, children’s literature is taken seriously by academe, and not dismissed as trivial. The Owl Service is one of the books that made that both possible and necessary. Fifty years after it was first published, we can see that it was always a classic.

Philip Pullman

CHAPTER 1

“How’s the bellyache, then?”

Gwyn stuck his head round the door. Alison sat in the iron bed with brass knobs. Porcelain columns showed the Infant Bacchus and there was a lump of slate under one leg because the floor dipped.

“A bore,” said Alison. “And I’m too hot.”

“Tough,” said Gwyn. “I couldn’t find any books, so I’ve brought one I had from school. I’m supposed to be reading it for Literature, but you’re welcome: it looks deadly.”

“Thanks anyway,” said Alison.

“Roger’s gone for a swim. You wanting company are you?”

“Don’t put yourself out for me,” said Alison.

“Right,” said Gwyn. “Cheerio.”

He rode sideways down the banisters on his arms to the first-floor landing.

“Gwyn!”

“Yes? What’s the matter? You OK?”

“Quick!”

“You want a basin? You going to throw up, are you?”

“Gwyn!”

He ran back. Alison was kneeling on the bed.

“Listen,” she said. “Can you hear that?”

“That what?”

“That noise in the ceiling. Listen.”

The house was quiet. Mostyn Lewis-Jones was calling after the sheep on the mountain: and something was scratching in the ceiling above the bed.

“Mice,” said Gwyn.

“Too loud,” said Alison.

“Rats, then.”

“No. Listen. It’s something hard.”

“They want their claws trimming.”

“It’s not rats,” said Alison.

“It is rats. They’re on the wood: that’s why they’re so loud.”

“I heard it the first night I came,” said Alison, “and every night since: a few minutes after I’m in bed.”

“That’s rats,” said Gwyn. “As bold as you please.”

“No,” said Alison. “It’s something trying to get out. The scratching’s a bit louder each night. And today – it’s the loudest yet – and it’s not there all the time.”

“They must be tired by now,” said Gwyn.

“Today – it’s been scratching when the pain’s bad. Isn’t that strange?”

“You’re strange,” said Gwyn. He stood on the bed, and rapped the ceiling. “You up there! Buzz off!”

The bed jangled as he fell, and landed hard, and sat gaping at Alison. His knocks had been answered.

“Gwyn! Do it again!”

Gwyn stood up.

Knock, knock.

Scratch, scratch.

Knock.

Scratch.

Knock knock knock.

Scratch scratch scratch.

Knock – knock knock.

Scratch – scratch scratch.

Gwyn whistled. “Hey,” he said. “These rats should be up the Grammar at Aberystwyth.” He jumped off the bed. “Now where’ve I seen it? – I know: in the closet here.”

Gwyn opened a door by the bedroom chimney. It was a narrow space like a cupboard, and there was a hatch in the ceiling.

“We need a ladder,” said Gwyn.

“Can’t you reach if you stand on the washbasin?” said Alison.

“Too chancy. We need a pair of steps and a hammer. The bolt’s rusted in. I’ll go and fetch them from the stables.”

“Don’t be long,” said Alison. “I’m all jittery.”

“ ‘Gwyn’s Educated Rats’: how’s that? We’ll make a packet on the telly.”

He came back with the stepladder, hammer and a cage trap.

“My Mam’s in the kitchen, so I couldn’t get bait.”

“I’ve some chocolate,” said Alison. “It’s fruit and nut: will that do?”

“Fine,” said Gwyn. “Give it us here now.”

He had no room to strike hard with the hammer, and rust and old paint dropped in his face.

“It’s painted right over,” he said. “No one’s been up for years. Ah. That’s it.”

The bolt broke from its rust. Gwyn climbed down for Alison’s torch. He wiped his face on his sleeve, and winked at her.

“That’s shut their racket, anyway.”

As he said this the scratching began on the door over his head, louder than before.

“You don’t have to open it,” said Alison.

“And say goodbye to fame and fortune?”

“Don’t laugh about it. You don’t have to do it for me. Gwyn, be careful. It sounds so sharp: strong and sharp.”

“Who’s laughing, girlie?” He brought a dry mop from the landing and placed the head against the door in the ceiling. The scratching had stopped. He pushed hard, and the door banged open. Dust sank in a cloud.

“It’s light,” said Gwyn. “There’s a pane of glass let in the roof.”

“Do be careful,” said Alison.

“‘“Is there anybody there?” said the Traveller’ – Yarawarawarawarawara!” Gwyn brandished the mop through the hole. “Nothing, see.”

He climbed until his head was above the level of the joists. Alison went to the foot of the ladder.

“A lot of muck and straw. Coming?”

“No,” said Alison. “I’d get hayfever in that dust. I’m allergic.”

“There’s a smell,” said Gwyn: “a kind of scent: I can’t quite – yes: it’s meadowsweet. Funny, that. It must be blowing from the river. The slates feel red hot.”

“Can you see what was making the noise?” said Alison.

Gwyn braced his hands on either side of the hatch and drew his legs up.

“It’s only a place for the water tanks, and that,” he said. “No proper floor. Wait a minute, though!”

“Where are you going? Be careful.” Alison heard Gwyn move across the ceiling.

In the darkest corner of the loft a plank lay over the joists, and on it was a whole dinner service: squat towers of plates, a mound of dishes, and all covered with grime, straw, droppings and blackened pieces of birds’ nests.

“What is it?” said Alison. She had come up the ladder and was holding a handkerchief to her nose.

“Plates. Masses of them.”

“Are they broken?”

“Nothing wrong with them as far as I can see, except muck. They’re rather nice – green and gold shining through the straw.”

“Bring one down, and we’ll wash it.”

Alison saw Gwyn lift a plate from the top of the nearest pile, and then he lurched, and nearly put his foot through the ceiling between the joists.

“Gwyn! Is that you?”

“Whoops!”

“Please come down.”

“Right. Just a second. It’s so blooming hot up here it made me go sken-eyed.”

He came to the hatch and gave Alison the plate.

“I think your mother’s calling you,” said Alison.

Gwyn climbed down and went to the top of the stairs.

“What you want, Mam?”

“Fetch me two lettuce from the kitchen garden!” His mother’s voice echoed from below. “And be sharp now!”

“I’m busy!”

“You are not!”

Gwyn pulled a face. “You clean the plate,” he said to Alison. “I’ll be right back.” Before he went downstairs Gwyn put the cage trap into the loft and closed the hatch.

“What did you do that for? You didn’t see anything, did you?” said Alison.

“No,” said Gwyn. “But there’s droppings. I still want to know what kind of rats it is can count.”

CHAPTER 2

Roger splashed through the shallows to the bank. A slab of rock stood out of the ground close by him, and he sprawled backwards into the foam of meadowsweet that grew thickly round its base. He gathered the stems in his arms and pulled the milky heads down over his face to shield him from the sun.

Through the flowers he could see a jet trail moving across the sky, but the only sounds were the river and a farmer calling sheep somewhere up the valley.

The mountains were gentle in the heat. The ridge above the house, crowned with a grove of fir trees, looked black against the summer light. He breathed the cool sweet air of the flowers. He felt the sun drag deep in his limbs.

Something flew by him, a blink of dark on the leaves. It was heavy, and fast, and struck hard. He felt the vibration through the rock, and he heard a scream.

Roger was on his feet, crouching, hands wide, but the meadow was empty, and the scream was gone: he caught its echo in the farmer’s distant voice and a curlew away on the mountain. There was no one in sight: his heart raced, and he was cold in the heat of the sun. He looked at his hands. The meadowsweet had cut him, lining his palm with red beads. The flowers stank of goat.

He leant against the rock. The mountains hung over him, ready to fill the valley. “Brrr—” He rubbed his arms and legs with his fists. The skin was rough with gooseflesh. He looked up and down the river, at the water sliding like oil under the trees and breaking on the stones. “Now what the heck was that? Acoustics? Trick acoustics? And those hills – they’d addle anyone’s brains.” He pressed his back against the rock. “Don’t you move. I’m watching you. That’s better – Hello?”

There was a hole in the rock. It was round and smooth, and it went right through from one side to the other. He felt it with his hand before he saw. Has it been drilled on purpose, or is it a freak? he thought. Waste of time if it isn’t natural: crafty precision job, though. “Gosh, what a fluke!” He had lined himself up with the hole to see if it was straight, and he was looking at the ridge of fir trees above the house. The hole framed the trees exactly … “Brrrr, put some clothes on.”

Roger walked up through the garden from the river.

Huw Halfbacon was raking the gravel on the drive in front of the house, and talking to Gwyn, who was banging lettuces together to shake the earth from the roots.

“Lovely day for a swim,” said Huw.

“Yes,” said Roger. “Perfect.”

“Lovely.”

“Yes.”

“You were swimming?” said Huw.

“That’s why I’m wearing trunks,” said Roger.

“It is a lovely day for that,” said Huw. “Swimming.”

“Yes.”

“In the water,” said Huw.

“I’ve got to get changed,” said Roger.

“I’ll come with you,” said Gwyn. “I want to have a talk.”

“That man’s gaga,” said Roger when they were out of hearing. “He’s so far gone he’s coming back.”

They sat on the terrace. It was shaded by its own steepness, and below them the river shone through the trees. “Hurry up then,” said Roger. “I’m cold.”

“Something happened just now,” said Gwyn. “There was scratching in the loft over Alison’s bedroom.”

“Mice,” said Roger.

“That’s what I said. But when I knocked to scare them away – they knocked back.”

“Get off!”

“They did. So I went up to have a look. There’s a pile of dirty plates up there: must be worth pounds.”

“Oh? That’s interesting. Have you brought them down?”

“One. Alison’s cleaning it. But what about the scratching?”

“Could be anything. These plates, though: what are they like? Why were they up there?”

“I couldn’t see much. I asked Huw about them.”

“Well?”

“He said, ‘Mind how you are looking at her.’ ”

“Who? Ali? What’s she got to do with it?”

“Not Alison. I don’t know who he meant. When I told him I’d found the plates he stopped raking for a moment and said that: ‘Mind how you are looking at her.’ Then you came.”

“I tell you, the man’s off his head. – Why’s he called Halfbacon, anyway?”

“It’s the Welsh: Huw Hannerhob,” said Gwyn. “Huw Halfbacon: Huw the Flitch: he’s called both.”

“It suits him.”

“It’s a nickname,” said Gwyn.

“What’s his real name?”

“I don’t think he knows. Roger? There’s one more thing. I don’t want you to laugh.”

“OK.”

“Well, when I picked up the top plate, I came over all queer. A sort of tingling in my hands, and everything went muzzy – you know how at the pictures it sometimes goes out of focus on the screen and then comes back? It was like that: only when I could see straight again, it was different somehow. Something had changed.”

“Like when you’re watching a person who’s asleep, and they wake up,” said Roger. “They don’t move, nothing happens, but you know they’re awake.”

“That’s it!” said Gwyn. “That’s it! Exactly! Better than what I was trying to say! By, you’re a quick one, aren’t you?”

“Can you tell me anything about a rock with a hole through it down by the river?” said Roger.

“A big slab?” said Gwyn.

“Yes, just in the meadow.”

“It’ll be the Stone of Gronw, but I don’t know why. Ask Huw. He’s worked at the house all his life.”

“No thanks. He’d give me the London Stockmarket Closing Report.”

“What do you want to know for, anyway?” said Gwyn.

“I was sunbathing there,” said Roger. “Are you coming to see how Ali’s managed with your plate?”

“In a sec,” said Gwyn. “I got to drop these in the kitchen for Mam. I’ll see you there.”

Roger changed quickly and went up to Alison. His bedroom was immediately below hers, on the first floor.

She was bending over a plate which she had balanced on her knees. The plate was covered with a sheet of paper and she was drawing something with a pencil.

“What’s this Gwyn says you’ve found?” said Roger.

“I’ve nearly finished,” said Alison. She kept moving the paper as she drew. “There! What do you think of that?” She was flushed.

Roger took the plate and turned it over. “No maker’s mark,” he said. “Pity. I thought it might have been a real find. It’s ordinary stuff: thick: not worth much.”

“Thick yourself! Look at the pattern!”

“Yes. – Well?”

“Don’t you see what it is?”

“An abstract design in green round the edge, touched up with a bit of rough gilding.”

“Roger! You’re being stupid on purpose! Look at that part. It’s an owl’s head.”

“—Yes? I suppose it is, if you want it to be. Three leafy heads with this kind of abstract flowery business in between each one. Yes: I suppose so.”

“It’s not abstract,” said Alison. “That’s the body. If you take the design off the plate and fit it together it makes a complete owl. See. I’ve traced the two parts of the design, and all you do is turn the head right round till it’s the other way up, and then join it to the top of the main pattern where it follows the rim of the plate. There you are. It’s an owl – head, wings and all.”