скачать книгу бесплатно

He said to the tabby, “I’m sorry. I’ll go away as soon as I am able. I don’t know how I got here. I thought I was going to die in the street.”

“You might have,” she said. “I found you and brought you here. I don’t think you’re very well. Hold still, and I’ll wash you a bit. Maybe that will make you feel a little better.”

Although Peter had acquired the body and the appearance of a white cat, he still thought and felt like a boy, and the prospect of being washed at that moment did not at all appeal to him, and particularly not at the hands, or rather tongue, of a bone-thin, scrawny tabby cat even if she had a sweet white face and a kind and gentle expression. What he really wanted was to stretch out on the heavy silk of the covers on the comfortable bed and just stay there and sleep and sleep.

But he remembered his manners and said, “No, thank you. I don’t want to trouble you. I don’t really think I would care—”

But the tabby cat interrupted him with a gentle “Hush! Of course you would. And I do it very well too.”

She reached out a scrawny part-white paw and laid it across his body, kindly but firmly, so that he was held down. And then with a long, stroking motion of her head and pink tongue she began to wash him, beginning at his nose, travelling up between the ears and down the back of his neck and the sides of his face.

And thereafter something strange happened to Peter, at least inside him. It was only a poor, thin, stray alley cat washing him, her rough tongue rasping against his fur and skin, but what it made him feel like was remembering when he had been very small and his mother had held him in her arms close to her. It was almost the very first thing he could remember.

He had been taking some of his early running-walking steps and had fallen and hurt himself. She had picked him up and held him tightly to her and he had cuddled his head into the warm place at her neck just beneath the chin. With her soft hands she had stroked the place where it hurt, and said, “There, Mother’ll make it all better. Now – it doesn’t hurt any more!” And it hadn’t. All the pain had gone, and he remembered only feeling safe and comfortable and contented.

That same warm, secure feeling was coming over him now as the little rough tongue rasped over his injured ear and down the long deep claw furrows torn into the skin of his shoulder and his side, and with each rasp, as her tongue passed over it, it seemed as though the pain that was there was erased as if by magic.

All the ache went out of his sore muscles too, as her busy tongue got around and behind and underneath, refreshing and relaxing them, and a most delicious kind of sleepiness began to steal over him. After all the dreadful things that had happened to him, it was so good to be cared for. He half expected to hear her say, “See, Mother’s making it all better! There! Now it doesn’t hurt any more …”

But she didn’t. She only kept on washing in a wonderful and soothing rhythm, and shortly Peter felt his own head moving in a kind of drowsy way in time with hers; the little motor of contentment was throbbing in his throat. Soon he nodded and went fast asleep.

When he awoke it was much later, because the light coming in through the grimy bit of window was quite different; the sun must have been well up in the sky, for a beam of it came in through a clear spot in the pane and made a little pool of brightness on the red silk cover of the enormous bed.

Peter rolled over into the middle of it and saw that he looked almost respectable again. Most of the coal grime and mud was off him, his white fur was dry and fluffed and now served again to hide and keep the air away from the ugly scars and scratches on his body. He felt that his torn ear had a droop to it, but it no longer hurt him and was quite dry and clean.

There was no sign of the tabby cat. Peter tried to stand up and stretch, but found that his legs were queerly wobbly and that he could not quite make it. And then he realised that he was weak with hunger as well as loss of blood, and that if he did not get something to eat soon he must surely perish. When was it he had last eaten? Why, ages ago, yesterday or the day before, Nanny had give him an egg and some greens, a little fruit jelly, and a glass of milk for lunch. It made him quite dizzy to think of it. When would he ever eat again?

Just then he heard a little soft, singing sound, a kind of musical call – “Errrp, purrrrrrow, urrrrrrp!” – that he found somehow extraordinarily sweet and thrilling. He turned to the direction from which it was coming and was just in time to see the tabby cat leap in through the space between the slats at the end of the bin. She was carrying something in her mouth.

In an instant she had jumped up on to the bed alongside him and laid it down.

“Ah,” she said, “that’s better. Feeling a little more fit after your sleep. Care to have a bit of mouse? I just caught it down the aisle near the lift. It’s really quite fresh. I wouldn’t mind sharing it with you. I could stand a snack myself. There you are. You have a go at it first.”

“Oh, n-no … No-no, thank you,” said Peter in horror. “N-not mouse. I couldn’t—”

“Why,” asked the tabby cat in great surprise, and with just a touch of indignation added, “What’s the matter with mouse?”

She had been so kind and he was so glad to see her again that Peter was most anxious not to hurt her feelings.

“Why, n-nothing, I’m sure. It’s … well, it’s just that I’ve never eaten one.”

“Never eaten one?” The tabby’s green eyes opened so wide that the flecks of gold therein almost dazzled Peter. “Well, I never! Not eaten one! You pampered, indoor, lap and parlour cats! I suppose it’s been fresh chopped liver and cat food out of a tin. You needn’t tell me. I’ve had plenty of it in my day. Well, when you’re off on your own and on the town with nobody giving you charity saucers of cream or left-over titbits, you soon learn to alter your tastes. And there’s no time like the present to begin. So hop to it, my lad, and get acquainted with mouse. You need a little something to set you up again.”

And with this she pushed the mouse over to him with her paw and then stood over Peter, eyeing him. There was a quiet forcefulness and gentle determination in her demeanour that made Peter a little afraid for a moment that if he didn’t do as she said, she might become angry. And besides, he had been taught that when people offered to share something with you at a sacrifice to themselves, it was not considered kind or polite to refuse.

“You begin at the head,” the tabby cat declared firmly.

Peter closed his eyes and took a small and tentative nibble.

To his intense surprise, it was simply delicious.

It was so good that before he realised it, Peter had eaten it up from the beginning of its nose to the very end of its tail. And only then did he experience a sudden pang of remorse at what he had done in his moment of greediness. He had very likely eaten his benefactress’s ration for the week. And by the look of her thin body and the ribs sticking through her fur, it had been longer than that since she had had a solid meal herself.

But she did not seem to mind in the least. On the contrary, she appeared to be pleased with him as she beamed down at him and said, “There, that wasn’t so bad, was it? My tail, but you were hungry!”

Peter said, “I’m sorry. I’m afraid I’ve eaten your dinner.”

The tabby smiled cheerfully. “Don’t give it another thought, laddie! Plenty more where that one came from.” But even though the smile and the voice were cheerful, yet Peter detected a certain wan quality about it that told him that this was not so, and that she had indeed made a great sacrifice for him, generously and with sweet grace.

She was eyeing him curiously now, it seemed to Peter almost as though she was expecting something of him, but he did not know what it was and so just lay quietly enjoying the feeling of being fed once again. The tabby opened her mouth as though she were going to say something, but then apparently thought better of it, turned, and gave her back a couple of quick licks.

Peter felt as if something he did not quite understand had sprung up to come between them, something awkward. To cover his own embarrassment about it, he asked: “Where am I – I mean, where are we?”

“Oh,” said the tabby, “this is where I live. Temporarily, of course. You know how it is with us, and if you don’t, you’ll soon find out. Though I must say it’s months since I’ve been disturbed here. I know a secret way in. It’s a warehouse where they store furniture for people. I picked this room because I liked the bed. There are lots of others.”

Now Peter remembered having learned in school what the crown and the ‘N’ stood for, and couldn’t resist showing off. He said, “The bed must have belonged to Napoleon, once. That’s his initial up there, and the crown. He was a great emperor.”

The tabby did not appear to be at all impressed. She merely remarked, “Was he, now? He must have been enormously large to want a bed this size. Still – I must say it is comfortable, and I don’t suppose he has any further use for it, for he hasn’t been here to fetch it in the last three months and neither has anybody else. You’re quite welcome to stay here as long as you like. I gather you’ve been turned out. Who was it mauled you? You were more than half dead when I found you last night lying in the street and dragged you in here.”

Peter told the tabby of his encounter with the yellow tomcat in the grain warehouse down by the docks. She listened to his tale with alert and evident sympathy, and when he had finished, nodded and said:

“Oh dear! Yes, that would be Dempsey. He’s the best fighter on the docks from Wapping all the way down to Limehouse Reach. Everybody steers clear of Dempsey. I say, you did have a nerve, telling him off! I admire you for that even if it was foolhardy. No house pets are much good at rough-and-tumble, and particularly against a champion like Dempsey.”

Peter liked the tabby’s admiration, he found, and swelled a little with it. He wished that he had managed to give Dempsey just one stiff blow to remember him by, and thought that perhaps some time he would. But then he recalled the big tom’s last words: “And don’t come back. Because next time you do, I’ll surely kill you,”and felt a little sick, particularly when he thought of the powerful and lightning-like buffets of those terrible paws that had so quickly robbed him of his senses and laid him open for the final attack which but for a bit of luck might have finished him. Assuredly he too would steer clear of Dempsey, but to the tabby he said:

“Oh, he wasn’t so much. If I hadn’t been so tired from running—”

The tabby smiled enigmatically. “Running from what, laddie?”

But before Peter could reply, she said: “Never mind, I know how it is. When you first find yourself on your own, everything frightens you. And don’t think that everybody doesn’t run. It’s nothing to be ashamed of. By the way, what is your name?”

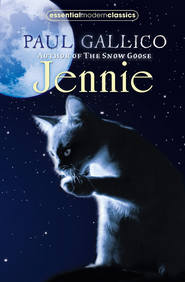

Peter told her. She said, “Hm … Mine’s Jennie. I’d like to hear your story. Care to tell it?”

Peter very much wanted to do so. But he found suddenly that he was a little timid because he was not at all sure how it would sound, and, even more important, whether the tabby would believe him and how she would take it. For it was certainly going to be a most odd tale.

CHAPTER FOUR (#ulink_9bbc3b0b-95b6-5930-8229-4fc6204724b2)

A Story is Told (#ulink_9bbc3b0b-95b6-5930-8229-4fc6204724b2)

BY AND LARGE, Peter made about as bad a beginning as could be when he said:

“I’m not really a cat, I’m a little boy. I mean actually, not so little. I’m eight.”

“You’re what?” Jennie gave a long, low growl, and her tail fluffed up to twice its size.

Peter could not imagine what he had said to make her angry, and he repeated hesitantly, “A boy—”

The tabby’s tail swelled another size larger and twitched nervously. Her eyes seemed to shoot sparks as she hissed: “I hate people!”

“Oh!” said Peter, for he was suddenly full of sympathy and understanding for the poor thin little tabby who had been so kind to him. “Somebody must have been horrible to you. But I love cats!”

Jennie looked mollified, and her tail began to subside. “Of course,” she said, “it’s just your imagination. I should have known. We’re always imagining things, like a leaf blowing in the wind being a mouse, or if there’s no leaf there at all, then we can imagine one, and when we’ve imagined it, go right on from there and imagine it isn’t a leaf at all but a mouse, or if we like, a whole lot of mice, and then we start pouncing on them. You just like to imagine that you’re a little boy, though what kind of a game you can make out of that I can’t see. Still—”

“Oh, please,” said Peter, interrupting. He could feel somehow that the tabby very much didn’t want him to be a boy, and yet, even at the risk of offending her, he knew that he must tell her the truth. “Please, I’m so sorry, but it is so. You must believe me. My name is Peter Brown, and I live in a flat with my mother and father and Nanny, in a house at Number 1A, Cavendish Mews. Or at least I did live there before—”

“Oh, come now,” protested Jennie, “don’t be silly. Anybody can see that you look like a cat, you feel like a cat, you smell like a cat, you purr like a cat, and you—” But here her voice trailed off into silence for a moment and her eyes grew wide again. “Oh dear,” she said then. “But there is something the matter. I’ve felt it all along. You don’t act like a cat—”

“Of course not,” Peter said, relieved that he might be believed at last.

But the tabby, her eyes growing wider and wider, wasn’t listening. She was going back over her acquaintance with Peter and enumerating the odd things that had happened since she had found him exhausted, wounded and half dead in the alley and had dragged him to her home, for what reason she did not know.

“You told off Dempsey, and right on his own premises, where he works. No sensible cat would have done that, no matter how brave. And besides, it’s against the rules.” She almost seemed to be ticking items off the end of her claws, though of course she wasn’t. “And then you didn’t want to eat mouse when you were literally starving – said you’d never had one, and then you ate it all up at one gobble, with never a thought that I might be hungry too. Not that I minded, but a real cat would never have done that. Oh, and then, of course – that’s what I was trying to remember! You ate mouse right on the silk counterpane where you’ve been sleeping, and you didn’t wash after you’d finished …”

Peter said, “Why should I? We always wash before eating. At least, Nanny always sends me into the bathroom and makes me clean my hands and face before sitting down to table.”

“Well, cats don’t!”declared Jennie decisively, “and it seems to me much the more sensible way. It’s after you’ve eaten you find yourself all greasy and sticky, with milk on your whiskers and gravy all over your fur if you’ve been in too much of a hurry. Oh dear!” she ended up. “That almost proves it. But I must say I’ve never heard of such a thing in all my life!”

Peter thought to himself, “She is good, and she has been kind to me, but she does love to chatter.” Aloud, he said, “If you would like me to tell you how it all happened, perhaps—”

“Yes, do, please,” said the tabby cat and settled herself more comfortably on the bed with her front paws tucked under her, “I should love to hear it.”

And so Peter began from the beginning and told her the whole story of what had happened to him.

Or rather he began away back before it began, really, and told her about his home in the Mews near the square and the little garden there inside the iron railings where Nanny took him to play every day after school when the weather was fine, and about his father who was a Colonel in the Guards and was away from home most of the time, first during the war when he was in Egypt and Italy, and then in France and Germany, and he hardly saw him at all, and then later in peacetime when he would come home now and then wearing a most beautiful uniform with blue trousers that had a red stripe down the side, except that as soon as he got into the house he went right into his room and changed it for an old brown tweed suit which wasn’t nearly as interesting or exciting.

Sometimes he stayed a little while for a chat or a romp with Peter, but usually he went off with Peter’s mother with golf clubs or fishing tackle in the car and they would stay away for days at a time. He would be left with only Cook and Nanny in the flat and it wasn’t much fun being alone, for even when he was with friends in the daytime, playing or visiting, it got very lonely at night without his father and mother. When they weren’t away on a trip together, they would dress up every evening and go out. And that was when he wished most that he had a cat of his own that would curl up at the foot of his bed, or cuddle, or play games just with him.

And he told the tabby all about his mother, how young and beautiful she was, so tall and slender, with light-coloured hair as soft as silk, that was the colour of the sunshine when it came in slantwise through the nursery window in the late afternoon, and how blue were her eyes and dark her lashes.

But particularly he remembered and told Jennie how good she smelled when she came in to say goodnight to him before going out for the evening, for when Peter’s father was away she was unhappy and bored and went off with friends a great deal seeking amusement.

It was always when he loved her most, Peter explained, when she came in looking and smelling like an angel, with clouds of beautiful materials around her, and her hair so soft and fragrant, when he so much wanted to be held to her, that she left him and went away.

Jennie nodded. “Mmmmm. I know. Perfume. I love things that smell good.”

She was indignant when Peter came to the part about not being allowed to have a cat because of the mess it might make around a small flat, and said, “Mess, indeed! We never make messes, unless we’re provoked, and then we do it on purpose. And can’t we just—!” But strangely enough she took Nanny’s part when Peter reached the point in his story about Nanny being afraid of cats and not liking them.

“There are people who don’t, you know,” she explained, when Peter expressed surprise, “and we can understand and respect them for it. Sometimes we like to tease them a little by rubbing up against them, or getting into their laps just to see them jump. They can’t help it any more than we can help not liking certain kinds of people and not wanting to have anything to do with them. But at least we know where we stand when we come across someone like your Nanny. It’s the people who love us, or say they love us and then hurt us, who …”

She did not finish the sentence, but turned away quickly, sat up, and began to wash violently down her back. But before she did, Peter thought that he had noticed the shine of tears in her eyes, though of course it couldn’t be so, since he had never heard of cats shedding tears. It was only later he was to learn that they could both laugh and cry.

Nevertheless, he felt that the tabby must be nursing some secret hurt, perhaps like his own, and in the hopes of taking her mind away from something sad, he launched into a description of the events leading up to his strange and mysterious transformation.

He began by telling about the tiger-striped kitten sunning and washing herself by the little garden in the centre of the square, and how he had wanted to catch her and hold her. Jennie showed immediate interest. She stopped washing and enquired: “How old was she? Was she pretty?”

“Oh yes,” said Peter, “very pretty, and full of fun …”

“Prettier than I?” Jennie enquired, with seeming nonchalance.

Peter had thought she had been, for she was like a round ball of fluff as he remembered, with most proud whiskers and two white and two brown feet. But he wouldn’t for anything have offended the tabby by telling her so. The truth was that for all her gentle ways and the kindly expression of her white face, Jennie was quite plain, with her small head, longish ears and slanted, half-Oriental eyes, and what with being so dreadfully thin making her bones stick out, Peter felt she was really nothing much to look at as cats went. But he was already old enough to know that one sometimes told small white lies to make people happy, and so he replied: “Oh, no! I think you’re beautiful!” After all, he had eaten her mouse.

“Do you really?” said Jennie, and for the first time since they had met, Peter heard a small purr coming from her. To cover her confusion she gave one of her paws a few tentative licks and then with a pleased smile on her thin face, enquired: “Well, and what happened then?”

And Peter thereupon told her all the rest of the story right to the end.

When he had finished with “… and then the next thing I knew, I opened my eyes and here I am”, there was a long silence. Peter felt tired from the effort of telling the story and reliving all the dreadful moments through which he had come, for he was yet far from having regained his full strength, even with rest and a meal.

Jennie, undeniably taken aback by the tale she had heard, appeared to be thinking hard, her eyes unblinking, and a faraway look in them, which, however, was not disbelief. It was clear from her demeanour that she apparently accepted Peter’s word that he was not a cat really, but a little boy, and the queer circumstances that had brought this about, and that it was something else that was occupying her mind.

Finally she turned her too-small, slender head towards Peter and said: “Well, what’s to be done?”

Peter said, “I don’t know, I’m sure. I suppose if I am a cat, I will just have to be one—”

The tabby put her gentle paw on his and said softly, “But, Peter, don’t you see, that’s just it! You said yourself that you didn’t feel as though you were a cat at all. If you’re going to be one, you must first learn how.”

“Oh dear,” said Peter, who never did much enjoy having to learn things, “is there more to being a cat than just liking to eat mice and purring?”

The little puss was genuinely shocked. “Is there more?” she repeated. “You couldn’t begin to imagine all the things there are! There must be hundreds. Why, if you left here right now and went out looking like a white cat, but feeling inside and thinking like a boy, I shouldn’t be inclined to give you more than ten minutes before you’d be in some terrible trouble again – like last night. It isn’t easy to be on your own, even if you have learned to know everything or nearly everything that a cat ought to know.”

Peter hadn’t thought about it that way, but there was no doubt she was right. If he had been himself in shape and form and had been locked out of the house, or had got lost from Nanny at the fun-fair, or in the park, he would have known enough to go straight up to a policeman and tell him his name and address and ask to be taken home. But he couldn’t very well do this in his present condition as a white cat with a slightly droopy left ear where it had been ripped by a yellow tom named Dempsey. And what was worse, now that the tabby had called it to his attention, he was a cat and didn’t know the first thing about how to behave as one. He began to feel frightened again, but different from the panic of the night before – it was a new kind of shakiness as though the bed and the ground and everything beneath his four paws was no longer very steady. He said somewhat piteously to the tabby: “Oh, Jennie – now I’m really frightened! What shall I do?”

She thought for a moment longer and then said, “I know! I’ll teach you.”

Peter felt such relief he could have cried. “Jennie dear! Would you? Could you?”

The expression on the face of the cat was positively angelic, or so Peter thought, and now she actually almost did look beautiful to him as she said: “But of course. After all, you’re my responsibility. I found you and brought you here. But one thing you must promise me if I try …”

Peter said, “Oh yes, I’ll promise anything—”

“First of all, do as I tell you until you can begin to look after yourself a little, but most important, never tell another soul your secret. I’ll know, but nobody else needs to, because they just wouldn’t understand. If we get into any kind of trouble, just let me do the talking. Never so much as hint or let on in any way to any other cat what you really are. Promise?”

Peter promised, and Jennie gave him a comradely little tap on the side of his head with her paw. Just the touch of her velvet pad and the simplicity of the caress made Peter feel happier already.

He said, “Won’t you tell me your story now, and who you are? I know nothing about you, and you’ve been so good to me …”

Jennie withdrew her paw, and a look of sadness came over her gentle face as she turned away for a moment. She said, “Later, perhaps, Peter. It is hard for me to speak about it now. And besides, you might not like it at all. Since you say you are a human and really not a cat at all, you would not be able to understand the way I feel and why I will never again live with people.”

“Please do tell me,” Peter pleaded. “And I will like it, I’m sure, because I like you.”

Jennie could not resist a small purr at Peter’s sincerity. She said, “You are a dear—” and then fell into reflective silence for a moment. Finally she seemed to make up her mind and said:

“See here, what is really important at the moment is for you to begin to learn something about being a cat, and the sooner we begin, the better. I shudder to think what might happen to you if you were alone again. How would it be if we had a lesson first? And of course nothing is more pressing than for you to learn how to wash. Afterwards, perhaps, I will be able to tell you my story.”

Peter hid his disappointment because she had been so kind to him and he did not wish to upset her. He merely said, “I’ll try, though I’m not very good at lessons.”

“I’ll help you, Peter,” Jennie reassured him, “and you’ll be surprised how much better you will feel when you know how. Because a cat must not only know how to wash, but WHEN to wash. You see, it’s something like this …”

CHAPTER FIVE (#ulink_b1a920da-b5da-51b8-bd07-be54d48fca98)