скачать книгу бесплатно

Now this opposition mainly comes from a lens focused on the world of creative people. The writers, the programmers, the designers, the makers, the product people. There are probably manual-labor domains where greater input does equal greater output, at least for a time.

But you rarely hear about people working three low-end jobs out of necessity wearing that grind with pride. It’s only the pretenders, those who aren’t exactly struggling for subsistence, who feel the need to brag about their immense sacrifice.

Entrepreneurship doesn’t have to be this epic tale of cutthroat survival. Most of the time it’s way more boring than that. Less jumping over exploding cars and wild chase scenes, more laying of bricks and applying another layer of paint.

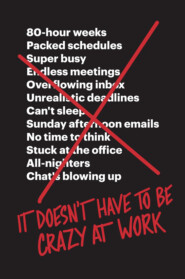

So you hereby have our permission to bury the hustle. To put in a good day’s work, day after day, but nothing more. You can play with your kids and still be a successful entrepreneur. You can have a hobby. You can take care of yourself physically. You can read a book. You can watch a silly movie with your partner. You can take the time to cook a proper meal. You can go for a long walk. You can dare to be completely ordinary every now and then.

Happy pacifists

The business world is obsessed with fighting and winning and dominating and destroying. This ethos turns business leaders into tiny Napoleons. It’s not enough for them to merely put their dent in the universe. No, they have to fucking own the universe.

Companies that live in such a zero-sum world don’t “earn market share” from a competitor, they “conquer the market.” They don’t just serve their customers, they “capture” them. They “target” customers, employ a sales “force,” hire “headhunters” to find new talent, pick their “battles,” and make a “killing.”

This language of war writes awful stories. When you think of yourself as a military commander who has to eliminate the enemy (your competition), it’s much easier to justify dirty tricks and anything-goes morals. And the bigger the battle, the dirtier it gets.

Like they say, all’s fair in love and war. Except this isn’t love, and it isn’t war. It’s business.

Sadly, it’s not easy to escape the business tropes of war and conquest. Every media outlet has a template for describing rival companies as warring factions. Sex sells, wars sell, and business battles serve as financial-page porn.

But that paradigm just doesn’t make any sense to us.

We come in peace. We don’t have imperial ambitions. We aren’t trying to dominate an industry or a market. We wish everyone well. To get ours, we don’t need to take theirs.

What’s our market share? Don’t know, don’t care. It’s irrelevant. Do we have enough customers paying us enough money to cover our costs and generate a profit? Yes. Is that number increasing every year? Yes. That’s good enough for us. Doesn’t matter if we’re 2 percent of the market or 4 percent or 75 percent. What matters is that we have a healthy business with sound economics that work for us. Costs under control, profitable sales.

Further, as far as market share goes, you’d need to define the market size accurately to define your share of it. As of the printing of this book, we have more than 100,000 companies that pay on a monthly basis for Basecamp. And that generates tens of millions of dollars in annual profit for us. We’re pretty sure that’s barely a blip of the overall market and that’s just fine with us. We’re serving our customers well, and they’re serving us well. That’s what matters. Doubling, tripling, quadrupling our market share doesn’t matter.

Lots of companies are driven by comparisons in general. Not just whether they’re first, second, or third in their industry, but how they stack up feature for feature with their closest competitors. Who’s getting which awards? Who’s raising more money? Who’s getting all the press? Why are they sponsoring that conference and not us?

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: