Полная версия:

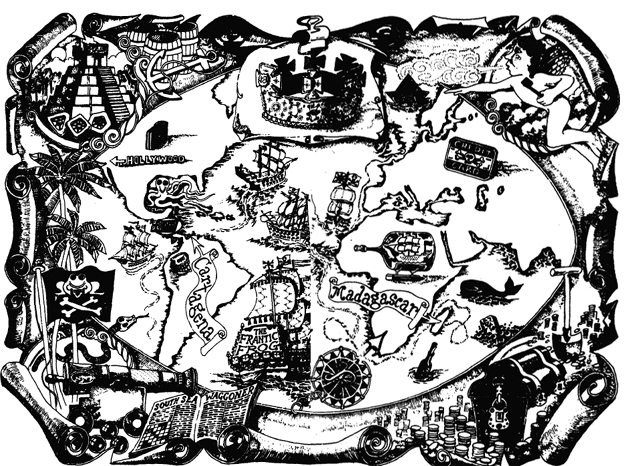

The Pyrates

George MacDonald Fraser

THE PYRATES

PRAISE

Praise for George MacDonald Fraser

‘It’s all there, right down to a Dead Man’s Chest, cleavages that are everything they should be and characters in sea-boots who say nothing but “Arr!” and “Me Hearty!” in a plot that is wonderfully absurd’ Financial Times

‘It’s great fun and rings true: a Highland Fling of a book’

Eric Linklater, author of The Wind on the Moon

‘Twenty-five years have not dimmed Mr Fraser’s recollections of those hectic days of soldiering. One takes leave of his characters with real and grateful regret’

Sir Bernard Fergusson, Sunday Times

‘A self-confident performance by an old hand. Mr Fraser clearly enjoys being master of such a wide and wild plot, and makes sure to leave room in it for his most famous creation, the eponymous hero of his Flashman adventure series’

New Yorker

‘Fabulous … you’ll want to stay up all night reading this one’

Washington Post

‘MacDonald Fraser falls into what these days is an exclusive group: the storyteller who can write’

D J Taylor, Sunday Times

‘Mr Fraser is a great historical novelist and in Black Ajax he is at the very top of his form. Damme if he ain’t’

Christopher Matthew, Daily Mail

‘This is not a flashy novel, wearing its learning noisily. It’s rigorous, intelligent, meticulously horrifying. Wonderfully well done’

Nicci Gerrard, Observer

‘The sense of front-line danger is palpable and the smell of action is remarkable. His descriptions of the sudden violent actions are breathtaking. This is battle as it is done’

Melvyn Bragg, Evening Standard

‘This is a book as good as anything Fraser has written … A moving and penetrating contribution to the literature of the Burma campaign’

Max Hastings, Daily Telegraph

‘It’s George MacDonald Fraser in top form on the Borders, juggling lairds and outlaws in bitter battling over disputed territory.’

Mail on Sunday, Books of the Year

‘The sense of front-line danger is palpable and the smell of action is remarkable. His descriptions of the sudden violent actions are breathtaking. This is battle as it is done’

Melvyn Bragg, Evening Standard

‘Twenty-five years have not dimmed Mr Fraser’s recollections of those hectic days of soldiering. One takes leave of his characters with real and grateful regret’

Sir Bernard Fergusson, Sunday Times

DEDICATION

IN MEMORY OF

The Most Reverend and Right Honourable

LANCELOT BLACKBURNE

(1658–1743)

Archbishop of York

and buccaneer

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Praise

Dedication

Book: The First

Chapter 1: The First

Chapter 2: The Second

Chapter 3: The Third

Chapter 4: The Fourth

Chapter 5: The Fifth

Chapter 6: The Sixth

Book: The Second

Chapter 7: The Seventh

Chapter 8: The Eighth

Chapter 9: The Ninth

Chapter 10: The Tenth

Chapter 11: The Eleventh

Chapter 12: The Twelfth

Chapter 13: The Thirteenth

Chapter 14: The Fourteenth

Book: The Third

Chapter 15: The Fifteenth

Chapter 16: The Sixteenth

Chapter 17: The Seventeenth

Chapter 18: The Eighteenth

Chapter 19: The Last

Afterthought

Influential: Bibliography

Keep Reading

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

CHAPTER

THE FIRST

It began in the old and golden days of England, in a time when all the hedgerows were green and the roads dusty, when hawthorn and wild roses bloomed, when big-bellied landlords brewed rich October ale at a penny a pint for rakish high-booted cavaliers with jingling spurs and long rapiers, when squires ate roast beef and belched and damned the Dutch over their claret while their faithful hounds slumbered on the rushes by the hearth, when summers were long and warm and drowsy, with honeysuckle and hollyhocks by cottage walls, when winter nights were clear and sharp with frost-rimmed moons shining on the silent snow, and Claud Duval and Swift Nick Nevison lurked in the bosky thickets, teeth gleaming beneath their masks as they heard the rumble of coaches bearing paunchy well-lined nabobs and bright-eyed ladies with powdered hair who would gladly tread a measure by the wayside with the gallant tobyman, and bestow a kiss to save their husbands’ guineas; an England where good King Charles lounged amiably on his throne, and scandalised Mr Pepys (or was it Mr Evelyn?) by climbing walls to ogle Pretty Nell; where gallants roistered and diced away their fathers’ fortunes; where beaming yokels in spotless smocks made hay in the sunshine and ate bread and cheese and quaffed foaming tankards fit to do G. K. Chesterton’s heart good; where threadbare pedlars with sharp eyes and long noses shared their morning bacon with weary travellers in dew-pearled woods and discoursed endlessly of ‘Hudibras’ and the glories of nature; where burly earringed smugglers brought their stealthy sloops into midnight coves, and stowed their hard-run cargoes of Hollands and Brussels and fragrant Virginia in clammy caverns; where the poachers of Lincolnshire lifted hares and pheasants by the bushel and buffeted gamekeepers and jumped o’er everywhere …

An England, in short, where justices were stout and gouty, peasants bluff and sturdy and content (but ready to turn out for Monmouth at a moment’s notice), merchant-fathers close and anxious, daughters sweet and winsome, good wives rosy and capable with bunches of keys and receipts for plum cordials, Puritans smug and sour and sanctimonious, fine ladies beautiful and husky-voiced and slightly wanton, foreigners suave and devious and given to using musky perfume, serving wenches red-haired and roguish-eyed with forty-inch busts, gentleman-adventurers proud and lithe and austere and indistinguishable from Basil Rathbone, and younger sons all eager and clean-limbed and longing for those far horizons beyond which lay fame and fortune and love and high adventure.

That was England, then; long before interfering social historians and such carles had spoiled it by discovering that its sanitation was primitive and its social services non-existent, that London’s atmosphere was so poisonous as to be unbreathable by all but the strongest lungs, that King Charles’s courtiers probably didn’t change their underwear above once a fortnight, that the cities stank fit to wake the dead and the countryside was largely either wilderness or rural slum, that religious bigotry, dental decay, political corruption, fleas, cruelty, poverty, disease, injustice, public hangings, malnutrition, and bear-baiting were rife, and there was hardly an economist or environmentalist or town planner or sociologist or anything progressive worth a damn. (There wasn’t even a London School of Economics, which is remarkable when you consider that Locke and Hobbes were loose about the place).

Happily, the stout justices and wenches and gallants and peasants and fine ladies – and even elegant Charles himself, who was nobody’s fool – never realised how backward and insanitary and generally awful they might look to the cold and all-too-selective eye of modern research, and if they had, it is doubtful if they would have felt any pang of guilt or shame, happy conscienceless rabble that they were. Indeed, his majesty would most likely have raised a politely sceptical eyebrow, the justices scowled resentfully, and the wenches, gallants, and peasants, being vulgar, gone into hoots of derisive mirth.

So, out of deference and gratitude to them all, and because history is very much what you want it to be, anyway, this story begins in that other, happier England of fancy rooted in truth, where dates and places and the chronology of events and people may shift a little here and there in the mirror of imagination, and yet not be thought false on that account. For it’s just a tale, and as Mark Twain pointed out, whether it happened or did not happen, it could have happened. And as all story-tellers know, whether they work with spoken words in crofts, or quills in Abbotsford, or cameras in Hollywood, it should have happened.

Thus:

It was on a day when, for example, King Charles was pleasantly tired after a ten-mile walk and was guiltily wondering whether he ought to preside at a meeting of his Royal Society, or take Frances Stuart to a very funny, dirty play whose jokes she would be too pure-minded to understand;

when Barbara Castlemaine was surveying her magnificence in the mirror, regretting (slightly) the havoc wrought by last night’s indulgence, and scheming how to foil her gorgeous rival, the Duchess of Portsmouth;

when, in far Jamaica, fat and yellow-faced old Henry Morgan was blowing impatiently into the whistle on the handle of his empty tankard for a refill, and wistfully reminiscing with the boys about flashing-eyed Spanish dames and treasure-stuffed churches of Panama and Portobello;

when Mr Evelyn was noting in his diary that the Duke of York’s dog always hid in the safest corner of the ship during sea-battles, and Mr Pepys was recording in his diary that on the previous night he had urinated in the fireplace because he couldn’t be bothered going out to the usual offices (and anyone checking these entries will find they are years apart, which gives some idea of the kind of story this is);

when Kirk’s mercenaries were tramping sweatily across the hot sands of the High Barbaree, licking parched lips at the thought of sparkling springs, or dusky Arab beauties in the suk of Tangier, or the day when their discharges would come through;

when a dear old tinker was dying of the cold, poor and humble and unnoticed by the great world, with the sound of choiring angels in his ears and no notion that one day he would be remembered as the greatest writer of plain English that ever was;

when the sound of the Dutchmen’s guns was still a fearsome memory along Thames-side, and Louis XIV was dreaming grandiose dreams and summoning his barber for his twice-weekly shave …

All these things were happening on the day when the story begins, but they don’t really matter, and have been set down for period flavour. The real principals in our melodrama were waiting in the wings, entirely unaware of each other or of the parts they were to play. They don’t actually come on just yet, but since they are the stars we should take a preliminary look at them.

First:

Captain Benjamin Avery, of the King’s Navy, fresh from distinguished service against the Sallee Rovers, in his decent lodging at Greenwich, making a careful toilet, brushing his teeth, combing his hair, adjusting his plain but spotless neckcloth, shooting his cuffs just so, and bidding a polite but aloof good morning to the adoring serving-maid as she brings in his breakfast of cereal, two boiled eggs, toast and coffee, and scurries out with a breathless, fluttering curtsey. Captain Avery straightens his coat and decides as he contemplates his splendid reflection that preferment and promotion must soon be the lot of such a brilliant and deserving young officer.

If you’d been there you would have seen his point, and the adoring maid’s. Captain Avery was everything that a hero of historical romance should be; he was all of Mr Sabatini’s supermen rolled into one, and he knew it. The sight of him was enough to make ordinary men feel that they were wearing odd socks, and women to go weak at the knees. Not that his dress was magnificent; it was sober, neat, and even plain, but as worn by Captain Avery it put mere finery to shame. Nor did he carry himself with ostentation, but with that natural dignity, nay austerity, coupled with discretion and modesty, which come of innate breeding. His finely-chiselled features bespoke both the man of action and the philosopher, their youthful lines tempered by a maturity beyond his years; there was beneath his composed exterior a hint of steely power, etc., etc. You get the picture.

For the record, this wonder boy was six feet two, with shoulders like a navvy and the waist of a ballerina; his legs were long and shapely, his hips narrow, and he moved like a classy welterweight coming out at the first bell. His face was straight off the B.O.P. cover, with its broad unclouded brow, long fair hair framing his smooth-shaven cheeks; his nose was classic, his mouth firm but not hard, his eyes clear dark grey and wide-set, his jaw strong and slightly cleft, and his teeth would have sent Kirk Douglas scuttling shamefaced to his dentist. His expression was at once noble, alert and intelligent, deferential yet commanding … sorry, we’re off again.

In short, Captain Avery was the young Errol Flynn, only more so, with a dash of Power and Redford thrown in; the answer to a maiden’s prayer, and between ourselves, rather a pain in the neck. For besides being gorgeous, he had a starred First from Oxford, could do the hundred in evens, played the guitar to admiration, helped old women across the street, kept his finger-nails clean, said his prayers, read Virgil and Aristophanes for fun, and generally made the Admirable Crichton look like an illiterate slob. However, he is vital if you are to get the customers in; more of him anon.

Secondly, and a sad come-down it is if you’re a purist, meet Colonel Tom Blood, cashiered, bought out, and all too obviously our Anti-Hero, in his lodgings, a seedy attic in Blackfriars, with a leaky ceiling and the paper peeling off the walls in damp strips. He has five pence in his pocket, his linen is foul, his boots are cracked, he hasn’t shaved, there’s nothing for breakfast but the stale heel of a loaf and pump water, and his railing harridan of a landlady has just shrieked abusively up the stairs to remind him that he is six weeks behind with the rent. But Colonel Blood is Irish and an optimist, and lies on his unmade bed with his hands behind his head, whistling and planning how to elope with a rich cit’s wife once he has brought the silly bag to the boil and she has assembled her valuables. He’d need a razor from somewhere, to be sure, and a clean shirt, but these – like poverty, hunger, and a shocking reputation – were trifles to a resourceful lad who had once come within an ace of stealing the Crown Jewels.

One should not be put off by the bad press given to Blood by that prejudiced old prude, Mr Evelyn, who once had dinner with him at Mr Treasurer’s, and kept a tight grip on his wallet during the meal, by the sound of it. “That impudent bold fellow”, he wrote of the gallant Colonel, “had not only a daring, but villainous unmerciful look, a false countenance, but very well spoken and dangerously insinuating”. Not quite fair to a dashing rascal who, if not classically handsome, was decidedly attractive in a Clark Gable-ish way, with his sleepy dark eyes, ready smile, and easy Irish charm. Tall, strong and well-made, perhaps not as slim as he would have liked, but trim and fast on his feet for all that; an affable, deceptively easygoing gentleman and quite a favourite with the less discriminating ladies who were beguiled by his trim moustache and lively conversation. A tricky, dangerous villain, though, when he had to be, which was deplorably often, for of all the Colonel’s many and curious talents, finding trouble was the first.

So there they were, the two of them, miles and poles apart, and hardly a thing in common except youth and vigour and blissful ignorance of the fate that was being determined for them four thousand sea-miles away …

For now the scene shifts abruptly, to grim Fort St Bartlemy, lonely outpost of England in the far Caribbean, where at the watergate of the great rockbound castle, bronzed and bare-backed seamen sweated in the humid tropic night as they carried massive iron-studded chests up from the boats at the sea-steps, and along the arched, stone-flagged tunnel to the strong room deep in the heart of that impregnable place. Guttering torches lit the scene as the sailors grunted and heaved and chewed quids of plug tobacco and spat and swore rich sea-oaths as they laboured, for every tarry-handed mother’s son of them had learned his trade in the Jeffrey Farnol School of Historical Dialect, and could growl “Belike” and “Look’ee” and “Ha – cheerly messmates all!” in that authentic Mummerset growl which would one day keep Robert Newton in gainful employment. So with hearty heave-ho-ing and avasting they worked, under the stern blue eye of their grizzled commander, a weather-beaten salt of suitably bluff appearance with a blue coat and brass-mounted telescope, who may well have been called Hawkins or Bransome, but not conceivably Vavasour d’Umfraville.

“Aaargh!” cried the burly captain, twice for emphasis. “Aaargh! Easy, handsomely, I say, wi’ they chests, rot ’ee! ’Tis ten thousand pound you’m carryin’, ye lubbers!” This was his normal habit of speech, since anything else would have been incomprehensible to his crew. “A pesky parlous cargo it be, an’ all, an’ glad am I to be rid on’t, burn me for a backstay else.”

“Not as glad as my garrison will be to see it,” replied the fort commandant, a stout and sunburned soldier who was equally perfect casting in his buff coat, large belly, and plumed hat. “Three years without pay is a long time in such lonely fortalice as this.” He hesitated, and ventured to add: “Damme for a lizard else.”

“For a what?” inquired the captain, rolling an eye.

“A lizard,” said the commandant defensively. “You know.”

“Aaargh!” said the captain thoughtfully. “A lizard, eh? Humph! Us seamen don’t use to swear by no crawlin’ land-lubberly varmints, us don’t. Handspikes an’ marlin-spikes an’ sich sailorly things be good enough fer we, by the powers, choke me wi’ a rammer else. Howbeit,” he went on, “I be mortal glad to see the last o’ these damned dollars; a thousand leagues from old England be a long way wi’ such a lading, through pirate waters an’ all, d’ye see, rot me for a Portingale pimp if it bain’t.” And he dashed the sweat from his brow with a horny hand. “Aye, split an’ sink me, a risky v’yage, look’ee, a passage right perilous, an’ happy I am ’tis done wi’, an’ they doubloons snug i’ the cellar at last, scuttle me for a—”

“How about some supper?” said the commandant quickly.

“Vittles, sez you!” cried the captain, rolling both eyes. “Why, then vittles it is, sez I, wi’ all my heart, aye, an’ a flagon o’ ale, devil a doubt, or Spanish vino, sa-ha! to wet our whistles, an’ damn all, wi’ a curse. Scupper me wi’ a handspike,” he added triumphantly, “else.”

The commandant having conceded game set and match, they rolled off to supper, while the toiling seamen heaved and beliked and spat as they trundled the last of the precious chests into the strongroom, and the great door clanged to and was locked with a ponderous key. Thereafter they repaired to mess with the garrison, while in the commandant’s chambers the officers supped off pepper-pot and flying-fish broiled, with many a tankard, and the sea captain amazed his hosts with the richness of his discourse. Sentries stood outside the strongroom, but the long stone tunnel to the watergate lay deserted, and from the sea-steps outside the fitful light of the torches shone on empty water to the little harbour entrance. Above on the battlements other sentries lolled – those dispensable sentries of fiction who doze at their posts in their ill-fitting uniforms, mere cannon-fodder to be knocked on the head or smothered by agile assailants, or at best wake up too late to fire a warning shot and yell “Turn out the … ugh!” If the commandant had lined the walls of that lonely fortress with his entire force, instead of boozing and stuffing and throwing his wig aside in the carouse, all might have been well, but of course he didn’t. They never do.

So within Fort St Bartlemy was all cheery complacency and unbuttoning, and without the tropic moon shone on that familiar scene … the grim silhouette of the castle, the torch-lit peace of the watergate, the wind sighing gently through the palm trees, the soft surf lapping the silver sand. All was tranquil, the moon’s wake throwing its golden shaft across the rum-dark sea, the scent of bougainvillea and pimento on the breeze, and one might have imagined the soft strains of “Spanish Ladies” on the lulling air, fading gradually away …

… to be replaced by another music, the almost imperceptible beat of something far out on the dark water, the chuckle of foam under a bow, the faint creak of cordage and timber, the soft whisper of a command, and the rising ghostly cadence of a wild sea-march as a great dark shadow came gliding, gliding out of the night. For an instant the moonlight touched the pale loom of canvas furled, then it was gone, and the dozing sentries never heard the soft plunge of oars, or caught the phosphorescent glitter of ruffled water, or the grating of long-boat bows on shingle, the splash of bare feet and sea-boots in the surf, the glint of steel, the clatter of gear instantly hushed, or the shadowy passage of silent figures slipping through the palm-groves. No, the sentries were dreaming of distant Devon or half-caste wenches or beer or whatever sleepy sentries dream about, and by the time one of them glanced seaward it was too late, as usual, because the Menace was there, unseen, crouched in disciplined quiet beneath the very castle wall on the narrow path that skirted round to the open, inviting, torch-lit watergate and its deserted steps, where only a few convenient boats rocked unguarded at their moorings.

Wolfish bearded faces in the shadows, earrings, head scarves, hairy drawers, dirty shirts open to the waist, bad breath, great buckled belts, cutlasses, knives and pistols gripped in gnarled and sweaty hands, and at their head, all in snowy white from breeches to head-kerchief, big as a house-side and nimble as a cat, Calico Jack Rackham, none other, cautiously edging his brutally handsome, square-chinned face round a corner of the watergate, grinning at the sight of the torch-lit empty tunnel, turning to his followers, motioning them to be ready for the assault, whispering his final orders. First among equals was Calico Jack, by reason of being literate and smart and able to navigate and do all things shipshape and Bristol fashion, look’ee, as his admiring associates often agreed. Also he was strong enough to break a penny between his fingers, which helps, and having served a turn in the Navy, he was reckoned dependable. In our day he would have been a paratroop sergeant, or a shop steward, or a moderate Labour M.P. He was a pirate because it offered a profitable field for his talents, and he was saving for his old age.

First behind him came Firebeard, six feet both ways, barrel-chested, with hands like earth-moving equipment, and so covered in the fuzz that gave him his nickname that he looked like a burst mattress with piggy eyes glinting out of it. He was enormous and roaring and ranting and wild and so thick he had forgotten his real name; he had been dropped on his head at an early age and never looked back. Nowadays he might have been an all-in wrestler or a Hollywood stuntman or an eccentric peer – or, indeed, all three. His idea of living was to hit people with anything handy, grab any valuables in sight, and blue the lot on wenches and drink. He was a pirate for these reasons, and also because he enjoyed bellowing those hearty songs which John Masefield would write in course of time. His eventual claim to fame would be as the model and inspiration of Edward Teach, who would copyright the habit in which Firebeard was at that very minute indulging, of tying lighted fire-crackers in his beard to terrify the enemy. He always did this before action, fumbling and cursing as the matches burned his huge clumsy fingers, while his comrades coughed and fanned the air.