Полная версия:

The Flashman Papers: The Complete 12-Book Collection

THE COMPLETE FLASHMAN PAPERS

FLASHMAN ROYAL FLASH FLASHMAN’S LADY FLASHMAN & THE MOUNTAIN OF LIGHT FLASH FOR FREEDOM! FLASHMAN & THE REDSKINS FLASHMAN AT THE CHARGE FLASHMAN IN THE GREAT GAME FLASHMAN AND THE ANGEL OF THE LORD FLASHMAN & THE DRAGON FLASHMAN ON THE MARCH FLASHMAN & THE TIGER

GEORGE MACDONALD FRASER

Copyright

These novels are entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in them are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Flashman first published in Great Britain by Herbert Jenkins Ltd 1969

Royal Flash first published in Great Britain by Barrie & Jenkins Ltd 1970

Flashman’s Lady first published in Great Britain by Barrie & Jenkins Ltd 1977

Flashman and the Mountain of Light first published in Great Britain by Harvill 1990

Flash for Freedom! first published in Great Britain by Barrie & Jenkins Ltd 1971

Flashman and the Redskins first published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1982

Flashman at the Charge first published in Great Britain by Barrie & Jenkins Ltd 1973

Flashman in the Great Game first published in Great Britain by Barrie & Jenkins Ltd 1975

Flashman and the Angel of the Lord first published in Great Britain by Harvill 1994

Flashman and the Dragon first published in Great Britain by Collins Harvill 1985

Flashman on the March first published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2005

Flashman and the Tiger first published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1999

Copyright © George MacDonald Fraser 1969, 1970, 1977, 1990, 1971, 1982, 1973, 1975, 1994, 1985, 2005, 1999

George MacDonald Fraser asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of these works

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Ebook Edition © NOVEMBER 2013 ISBN: 9780007532513

Version: 2017-11-06

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

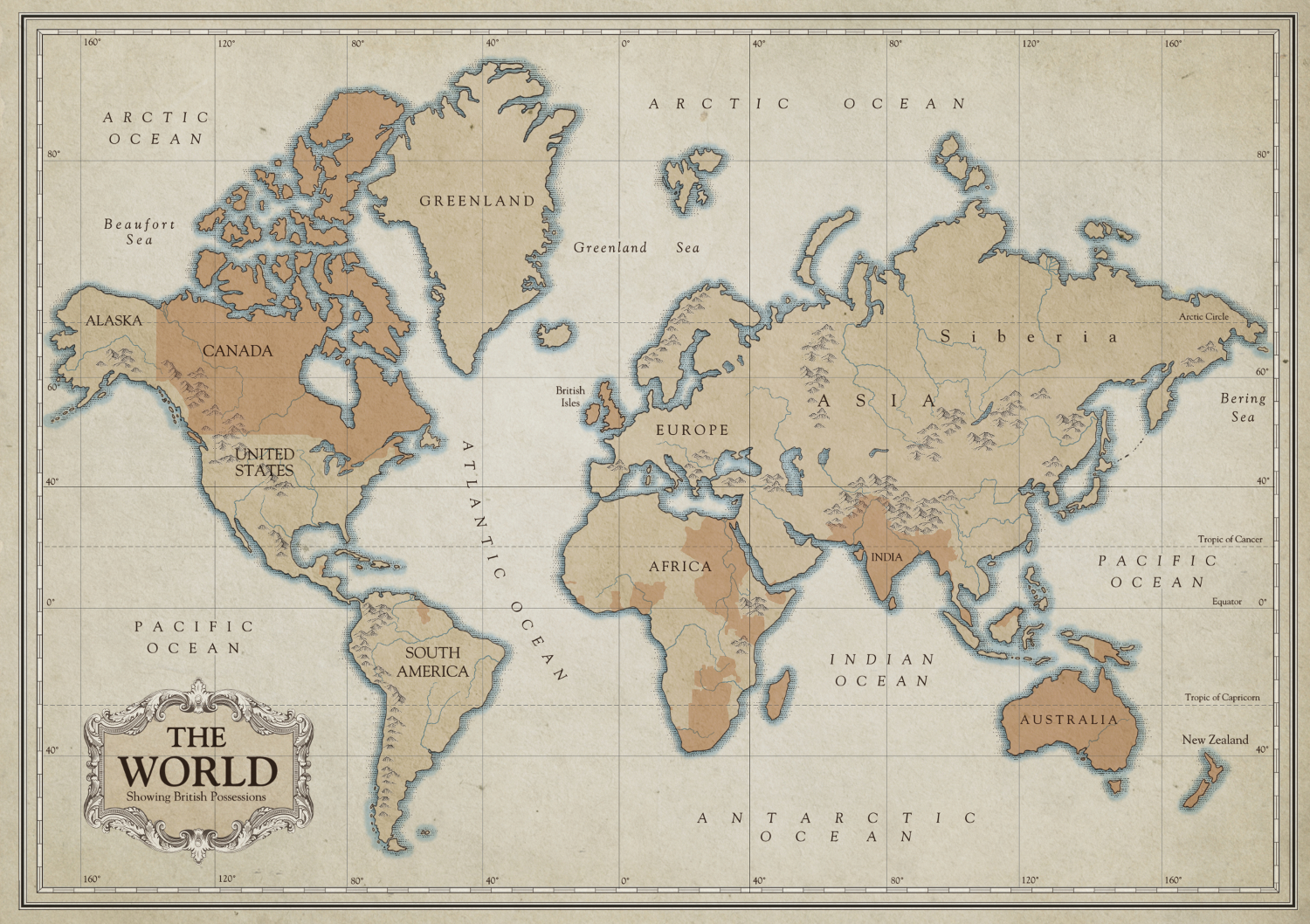

Map

Flashman

Royal Flash

Flashman’s Lady

Flashman & the Mountain of Light

Flash for Freedom!

Flashman & the Redskins

Flashman at the Charge

Flashman in the Great Game

Flashman & the Angel of the Lord

Flashman & the Dragon

Flashman on the March

Flashman & the Tiger

Keep Reading

About the Author

Also by George MacDonald Fraser

About the Publisher

Map

FLASHMAN

From The Flashman Papers, 1839–42

Edited and Arranged by

GEORGE MACDONALD FRASER

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters, and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Herbert Jenkins Ltd 1969

Copyright © George MacDonald Fraser 1969

George MacDonald Fraser asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780006511250

Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2011 ISBN: 9780007325689

Version: 2017-11-06

Dedication

FOR KATH

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Explanatory Note

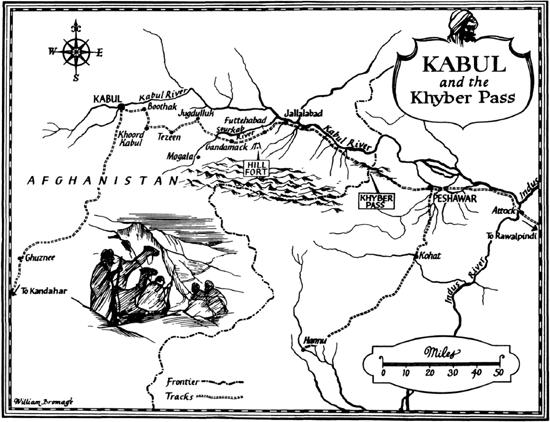

Map

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Glossary

Notes

Explanatory Note

The great mass of manuscript known as the Flashman Papers was discovered during a sale of household furniture at Ashby, Leicestershire, in 1965. The papers were subsequently claimed by Mr Paget Morrison, of Durban, South Africa, the nearest known living relative of their author.

A point of major literary interest about the papers is that they clearly identify Flashman, the school bully of Thomas Hughes’ Tom Broun’s Schooldays, with the celebrated Victorian soldier of the same name. The papers are, in fact, Harry Flashman’s personal memoirs from the day of his expulsion from Rugby School in the late 1830s to the early years of the present century. He appears to have written them some time between 1900 and 1905, when he must have been over eighty. It is possible that he dictated them.

The papers, which had apparently lain untouched for fifty years, in a tea chest, until they were found in the Ashby saleroom, were carefully wrapped in oilskin covers. From correspondence found in the first packet, it is evident that their original discovery by his relatives in 1915 after the great soldier’s death caused considerable consternation; they seem to have been unanimously against publication of their kinsman’s autobiography – one can readily understand why – and the only wonder is that the manuscript was not destroyed.

Fortunately, it was preserved, and what follows is the content of the first packet, covering Flashman’s early adventures. I have no reason to doubt that it is a completely truthful account; where Flashman touches on historical fact he is almost invariably accurate, and readers can judge whether he is to be believed or not on more personal matters.

Mr Paget Morrison, knowing of my interest in this and related subjects, asked me to edit the papers. Beyond correcting some minor spelling errors, however, there has been no editing to do. Flashman had a better sense of narrative than I have, and I have confined myself to the addition of a few historical notes.

The quotation from Tom Brown’s Schooldays was pasted to the top page of the first packet; it had evidently been cut from the original edition of 1856.

G. M. F.

One fine summer evening Flashman had been regaling himself on gin-punch, at Brownsover; and, having exceeded his usual limits, started home uproarious. He fell in with a friend or two coming back from bathing, proposed a glass of beer, to which they assented, the weather being hot, and they thirsty souls, and unaware of the quantity of drink which Flashman had already on board. The short result was, that Flashy became beastly drunk. They tried to get him along, but couldn’t; so they chartered a hurdle and two men to carry him. One of the masters came upon them, and they naturally enough fled. The flight of the rest excited the master’s suspicions, and the good angel of the fags incited him to examine the freight, and, after examination, to convoy the hurdle himself up to the School-house; and the Doctor, who had long had his eye on Flashman, arranged for his withdrawal next morning.

– THOMAS HUGHES, Tom Brown’s Schooldays.

Map

Chapter 1

Hughes got it wrong, in one important detail. You will have read, in Tom Brown, how I was expelled from Rugby School for drunkenness, which is true enough, but when Hughes alleges that this was the result of my deliberately pouring beer on top of gin-punch, he is in error. I knew better than to mix my drinks, even at seventeen.

I mention this, not in self-defence, but in the interests of strict truth. This story will be completely truthful; I am breaking the habit of eighty years. Why shouldn’t I? When a man is as old as I am, and knows himself thoroughly for what he was and is, he doesn’t care much. I’m not ashamed, you see; never was – and I have enough on what Society would consider the credit side of the ledger – a knighthood, a Victoria Cross, high rank, and some popular fame. So I can look at the picture above my desk, of the young officer in Cardigan’s Hussars; tall, masterful, and roughly handsome I was in those days (even Hughes allowed that I was big and strong, and had considerable powers of being pleasant), and say that it is the portrait of a scoundrel, a liar, a cheat, a thief, a coward – and, oh yes, a toady. Hughes said more or less all these things, and his description was pretty fair, except in matters of detail such as the one I’ve mentioned. But he was more concerned to preach a sermon than to give facts.

But I am concerned with facts, and since many of them are discreditable to me, you can rest assured they are true.

At all events, Hughes was wrong in saying I suggested beer. It was Speedicut who ordered it up, and I had drunk it (on top of all those gin-punches) before I knew what I was properly doing. That finished me; I was really drunk then – “beastly drunk”, says Hughes, and he’s right – and when they got me out of the “Grapes” I could hardly see, let alone walk. They bundled me into a sedan, and then a beak hove in sight and Speedicut lived up to his name and bolted. I was left sprawling in the chair, and up came the master and saw me. It was old Rufton, one of Arnold’s housemasters.

“Good God!” he said. “It’s one of our boys – drunk!”

I can still see him goggling at me, with his great pale gooseberry eyes and white whiskers. He tried to rouse me, but he might as well have tried to wake a corpse. I just lay and giggled at him. Finally he lost his temper, and banged the top of the chair with his cane and shouted:

“Take him up, chairmen! Take him to the School! He shall go before the Doctor for this!”

So they bore me off in procession, with old Rufton raging behind about disgusting excesses and the wages of sin, and old Thomas and the chairmen took me to the hospital, which was appropriate, and left me on a bed to sober up. It didn’t take me long, I can tell you, as soon as my mind was clear enough to think what would come of it. You know what Arnold was like, if you have read Hughes, and he had no use for me at the best of times. The least I could expect was a flogging before the school.

That was enough to set me in a blue funk, at the very thought, but what I was really afraid of was Arnold himself.

They left me in the hospital perhaps two hours, and then old Thomas came to say the Doctor wanted to see me. I followed him downstairs and across to the School-house, with the fags peeping round corners and telling each other that the brute Flashy had fallen at last, and old Thomas knocked at the Doctor’s door, and the voice crying “Come in!” sounded like the crack of doom to me.

He was standing before the fireplace, with his hands behind looping up his coat-tails, and a face like a Turk at a christening. He had eyes like sabre-points, and his face was pale and carried that disgusted look that he kept for these occasions. Even with the liquor still working on me a little I was as scared in that minute as I’ve ever been in my life – and when you have ridden into a Russian battery at Balaclava and been chained in an Afghan dungeon waiting for the torturers, as I have, you know what fear means. I still feel uneasy when I think of him, and he’s been dead sixty years.

He was live enough then. He stood silent a moment, to let me stew a little. Then:

“Flashman,” says he, “there are many moments in a schoolmaster’s life when he must make a decision, and afterwards wonder whether he was right or not. I have made a decision, and for once I am in no doubt that I am right. I have observed you for several years now, with increasing concern. You have been an evil influence in the school. That you are a bully, I know; that you are untruthful, I have long suspected; that you are deceitful and mean, I have feared; but that you had fallen so low as to be a drunkard – that, at least, I never imagined. I have looked in the past for some signs of improvement in you, some spark of grace, some ray of hope that my work here had not, in your case, been unsuccessful. It has not come, and this is the final infamy. Have you anything to say?”

He had me blubbering by this time; I mumbled something about being sorry.

“If I thought for one moment,” says he, “that you were sorry, that you had it in you to show true repentance, I might hesitate from the step that I am about to take. But I know you too well, Flashman. You must leave Rugby tomorrow.”

If I had had my wits about me I suppose I should have thought this was no bad news, but with Arnold thundering I lost my head.

“But, sir,” I said, still blubbering, “it will break my mother’s heart!”

He went pale as a ghost, and I fell back. I thought he was going to hit me.

“Blasphemous wretch!” he cried – he had a great pulpit trick with phrases like those – “your mother has been dead these many years, and do you dare to plead her name – a name that should be sacred to you – in defence of your abominations? You have killed any spark of pity I had for you!”

“My father –”

“Your father,” says he, “will know how to deal with you. I hardly think,” he added, with a look, “that his heart will be broken.” He knew something of my father, you see, and probably thought we were a pretty pair.

He stood there drumming his fingers behind him a moment, and then he said, in a different voice:

“You are a sorry creature, Flashman. I have failed in you. But even to you I must say, this is not the end. You cannot continue here, but you are young, Flashman, and there is time yet. Though your sins be as red as crimson, yet shall they be as white as snow. You have fallen very low, but you can be raised up again.…”

I haven’t a good memory for sermons, and he went on like this for some time, like the pious old hypocrite that he was. For he was a hypocrite, I think, like most of his generation. Either that or he was more foolish than he looked, for he was wasting his piety on me. But he never realised it.

Anyway, he gave me a fine holy harangue, about how through repentance I might be saved – which I’ve never believed, by the way. I’ve repented a good deal in my time, and had good cause, but I was never ass enough to suppose it mended anything. But I’ve learned to swim with the tide when I have to, so I let him pray over me, and when he had finished I left his study a good deal happier than when I went in. I had escaped flogging, which was the main thing; leaving Rugby I didn’t mind a button. I never much cared for the place, and the supposed disgrace of expulsion I didn’t even think about. (They had me back a few years ago to present prizes; nothing was said about expulsion then, which shows that they are just as big hypocrites now as they were in Arnold’s day. I made a speech, too; on Courage, of all things.)

I left the school next morning, in the gig, with my box on top, and they were damned glad to see me go, I expect. Certainly the fags were; I’d given them toco in my time. And who should be at the gate (to gloat, I thought at first, but it turned out otherwise) but the bold Scud East. He even offered me his hand.

“I’m sorry, Flashman,” he said.

I asked him what he had to be sorry for, and damned his impudence.

“Sorry you’re being expelled,” says he.

“You’re a liar,” says I. “And damn your sorrow, too.”

He looked at me, and then turned on his heel and walked off. But I know now that I misjudged him then; he was sorry, heaven knows why. He’d no cause to love me, and if I had been him I’d have been throwing my cap in the air and hurrahing. But he was soft: one of Arnold’s sturdy fools, manly little chaps, of course, and full of virtue, the kind that schoolmasters love. Yes, he was a fool then, and a fool twenty years later, when he died in the dust at Cawnpore with a Sepoy’s bayonet in his back. Honest Scud East; that was all that his gallant goodness did for him.

Chapter 2

I didn’t linger on the way home. I knew my father was in London, and I wanted to get over as soon as I could the painful business of telling him I had been kicked out of Rugby. So I decided to ride to town, letting my bags follow, and hired a horse accordingly at the “George”. I am one of those who rode as soon as he walked – indeed, horsemanship and my trick of picking up foreign tongues have been the only things in which you could say I was born gifted, and very useful they have been.

So I rode to town, puzzling over how my father would take the good news. He was an odd fish, the guv’nor, and he and I had always been wary of each other. He was a nabob’s grandson, you see, old Jack Flashman having made a fortune in America out of slaves and rum, and piracy, too, I shouldn’t wonder, and buying the place in Leicestershire where we have lived ever since. But for all their moneybags, the Flashmans were never the thing – “the coarse streak showed through, generation after generation, like dung beneath a rosebush,” as Greville said. In other words, while other nabob families tried to make themselves pass for quality, ours didn’t, because we couldn’t. My own father was the first to marry well, for my mother was related to the Pagets, who as everyone knows sit on the right hand of God. As a consequence he kept an eye on me to see if I gave myself airs; before mother died he never saw much of me, being too busy at the clubs or in the House or hunting – foxes sometimes, but women mostly – but after that he had to take some interest in his heir, and we grew to know and mistrust each other.

He was a decent enough fellow in his way, I suppose, pretty rough and with the devil’s own temper, but well enough liked in his set, which was country-squire with enough money to pass in the West End. He enjoyed some lingering fame through having gone a number of rounds with Cribb, in his youth, though it’s my belief that Champion Tom went easy with him because of his cash. He lived half in town, half in country now, and kept an expensive house, but he was out of politics, having been sent to the knacker’s yard at Reform. He was still occupied, though, what with brandy and the tables, and hunting – both kinds.

I was feeling pretty uneasy, then, when I ran up the steps and hammered on the front door. Oswald, the butler, raised a great cry when he saw who it was, because it was nowhere near the end of the half, and this brought other servants: they scented scandal, no doubt.

“My father’s home?” I asked, giving Oswald my coat and straightening my neck-cloth.

“Your father, to be sure, Mr Harry,” cried Oswald, all smiles. “In the saloon this minute!” He threw open the door, and cried out: “Mr Harry’s home, sir!”

My father had been sprawled on a settee, but he jumped up when he saw me. He had a glass in his hand and his face was flushed, but since both those things were usual it was hard to say whether he was drunk or not. He stared at me, and then greeted the prodigal with:

“What the hell are you doing here?”

At most times this kind of welcome would have taken me aback, but not now. There was a woman in the room, and she distracted my attention. She was a tall, handsome, hussy-looking piece, with brown hair piled up on her head and a come-and-catch-me look in her eye. “This is the new one,” I thought, for you got used to his string of madames; they changed as fast as the sentries at St James’.

She was looking at me with a lazy, half-amused smile that sent a shiver up my back at the same time as it made me conscious of the schoolboy cut of my clothes. But it stiffened me, too, all in an instant, so that I answered his question pat:

“I’ve been expelled,” I said, as cool as I could.

“Expelled? D’ye mean thrown out? What the devil for, sir?”

“Drunkenness, mainly.”

“Mainly? Good God!” He was going purple. He looked from the woman back to me, as though seeking enlightenment. She seemed much amused by it, but seeing the old fellow in danger of explosion I made haste to explain what had happened. I was truthful enough, except that I made rather more of my interview with Arnold than was the case; to hear me you would suppose I had given as good as I got. Seeing the female eyeing me I acted pretty offhand, which was risky, perhaps, with the guv’nor in his present mood. But to my surprise he took it pretty well; he had never liked Arnold, of course.