Полная версия:

Flashman in the Great Game

Copyright

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Barrie & Jenkins 1975

Copyright © George MacDonald Fraser 1975

How Did I Get the Idea of Flashman? © The Beneficiaries of the Literary Estate of George MacDonald Fraser 2015

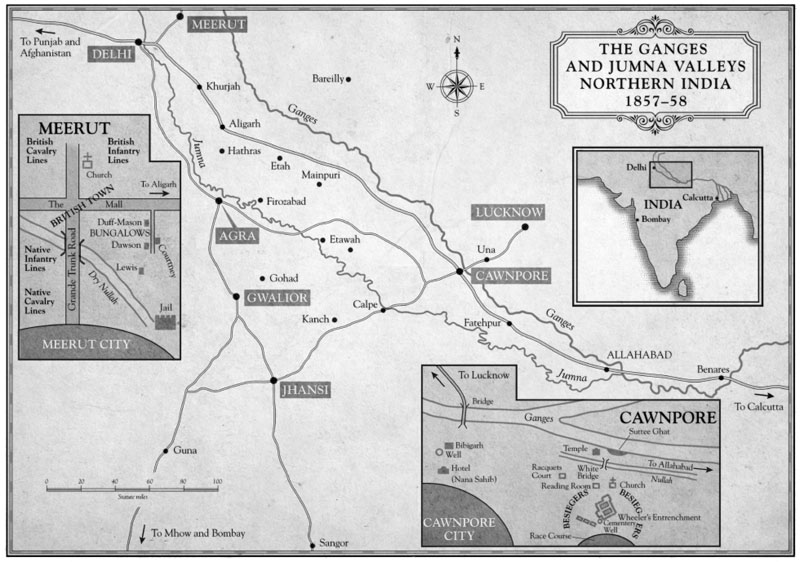

Map © John Gilkes 2015

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover illustration © Gino D’Achille

George MacDonald Fraser asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on historical events and figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007217199

Ebook Edition © 2015 ISBN: 9780007449514

Version: 2015-07-14

The following piece was found in the author’s study in 2013 by the Estate of George MacDonald Fraser.

How Did I Get the Idea of Flashman?

‘How did you get the idea of Flashman?’ and ‘When are we going to get his U.S. Civil War memoirs?’ are questions which I have ducked more often than I can count. To the second, my invariable response is ‘Oh, one of these days’. Followed, when the inquirer is an impatient American, by the gentle reminder that to an old British soldier like Flashman the unpleasantness between the States is not quite the most important event of the nineteenth century, but rather a sideshow compared to the Mutiny or Crimea. Before they can get indignant I add hastily that his Civil War itinerary is already mapped out; this is the only way of preventing them from telling me what it ought to be.

To the question, how did I get the idea, I simply reply that I don’t know. Who ever knows? Anthony Hope conceived The Prisoner of Zenda on a walk from Westminster to the Temple, but I doubt if he could have said, after the calendar month it took him to write the book, what triggered the idea. In my case, Flashman came thundering out of the mists of forty years living and dreaming, and while I can list the ingredients that went to his making, heaven only knows how and when they combined.

One thing is sure: the Flashman Papers would never have been written if my fellow clansman Hugh Fraser, Lord Allander, had confirmed me as editor of the Glasgow Herald in 1966. But he didn’t, the canny little bandit, and I won’t say he was wrong. I wouldn’t have lasted in the job, for I’d been trained in a journalistic school where editors were gods, and in three months as acting chief my attitude to management, front office, and directors had been that of a seigneur to his serfs – I had even put Fraser’s entry to the House of Lords on an inside page, assuring him that it was not for the Herald, his own paper, to flaunt his elevation, and that a two-column picture of him was quite big enough. How cavalier can you get?

And doubtless I had other editorial shortcomings. In any event, faced with twenty years as deputy editor (which means doing all the work without getting to the big dinners), I promised my wife I would ‘write us out of it’. In a few weeks of thrashing the typewriter at the kitchen table in the small hours, Flashman was half-finished, and likely to stay that way, for I fell down a waterfall, broke my arm, and lost interest – until my wife asked to read what I had written. Her reaction galvanised me into finishing it, one draft, no revisions, and for the next two years it rebounded from publisher after publisher, British and American.

I can’t blame them: the purported memoir of an unregenerate blackguard, bully, and coward resurrected from a Victorian school story is a pretty eccentric subject. By 1968 I was ready to call it a day, but thanks to my wife’s insistence and George Greenfield’s matchless knowledge of the publishing scene, it found a home at last with Herbert Jenkins, the manuscript looking, to quote Christopher MacLehose, as though it had been round the world twice. It dam’ nearly had.

They published it as it stood, with (to me) bewildering results. It wasn’t a bestseller in the blockbuster sense, but the reviewers were enthusiastic, foreign rights (starting with Finland) were sold, and when it appeared in the U.S.A. one-third of forty-odd critics accepted it as a genuine historical memoir, to the undisguised glee of the New York Times, which wickedly assembled their reviews. ‘The most important discovery since the Boswell Papers’ is the one that haunts me still, for if I was human enough to feel my lower ribs parting under the strain, I was appalled, sort of.

You see, while I had written a straightforward introduction describing the ‘discovery’ of the ‘Papers’ in a saleroom in Ashby-de-la-Zouche (that ought to have warned them), and larded it with editorial ‘foot-notes’, there had been no intent to deceive; for one thing, while I’d done my best to write, first-person, in Victorian style, I’d never imagined that it would fool anybody. Nor did Herbert Jenkins. And fifty British critics had recognised it as a conceit. (The only one who was half-doubtful was my old chief sub on the Herald; called on to review it for another paper, he demanded of the Herald’s literary editor: ‘This book o’ Geordie’s isnae true, is it?’ and on being assured that it wasn’t, exclaimed: ‘The conniving bastard!’, which I still regard as a high compliment.)

With the exception of one left-wing journal which hailed it as a scathing attack on British imperialism, the press and public took Flashman, quite rightly, at face value, as an adventure story dressed up as the memoirs of an unrepentant old cad who, despite his cowardice, depravity and deceit, had managed to emerge from fearful ordeals and perils an acclaimed hero, his only redeeming qualities being his humour and shameless honesty as a memorialist. I was gratified, if slightly puzzled to learn that the great American publisher, Alfred Knopf, had said of the book: ‘I haven’t heard this voice in fifty years’, and that the Commissioner of Metropolitan Police was recommending it to his subordinates. My interest increased as I wrote more Flashman books, and noted the reactions.

I was, several critics agreed, a satirist. Taking revenge on the nineteenth century on behalf of the twentieth, said one. Waging war on Victorian hypocrisy, said another. Plainly under the influence of Conrad, said yet another. A full-page review in a German paper took me flat aback when my eye fell on the word ‘Proust’ in the middle of it. I don’t read German, so for all I know the review may have been maintaining that Proust was a better stand-off half than I was, or used more semi-colons. But there it was, and it makes you think. And a few years ago a highly respected religious journal said that the Flashman Papers deserved recognition as the work of a sensitive moralist, and spoke of service not only to literature and history, but to the study of ethics.

My instant reaction to this was to paraphrase Poins: ‘God send me no worse fortune, but I never said so!’ while feeling delighted that someone else had said it, and then reflecting solemnly that this was a far cry from long nights with cold tea and cigarettes, scheming to get Flashman into the passionate embrace of the Empress of China, or out of the toils of a demented dwarf on the edge of a snake-pit. But now, beyond remarking that the anti-imperial left-winger was sadly off the mark, that the Victorians were mere amateurs in hypocrisy compared to our own brainwashed, sanctimonious, self-censoring and terrified generation, and that I hadn’t read a word of Conrad by 1966 (and my interest in him since has been confined to Under Western Eyes, in the hope that I might persuade Dick Lester to film it as only he could), I have no comments to offer on opinions of my work. I know what I’m doing – at least, I think I do – and the aim is to entertain (myself, for a start) while being true to history, to let Flashman comment on human and inhuman nature, and devil take the romantics and the politically correct revisionists both. But my job is writing, not explaining what I’ve written, and I’m well content and grateful to have others find in Flashy whatever they will (I’ve even had letters psychoanalysing the brute), and return to the question with which I began this article.

A life-long love affair with British imperial adventure, fed on tupenny bloods, the Wolf of Kabul and Lionheart Logan (where are they now?), the Barrack-Room Ballads, films like Lives of a Bengal Lancer and The Four Feathers, and the stout-hearted stories for boys which my father won as school prizes in the 1890s; the discovery, through Scott and Sabatini and Macaulay, that history is one tremendous adventure story; soldiering in Burma, and seeing the twilight of the Raj in all its splendour; a newspaper-trained lust for finding the truth behind the received opinion; being a Highlander from a family that would rather spin yarns than eat … I suppose Flashman was born out of all these things, and from reading Tom Brown’s Schooldays as a child – and having a wayward cast of mind.

Thanks to that contrary streak (I always half-hoped that Rathbone would kill Flynn, confounding convention and turning the story upside down – Basil gets Olivia, Claude Rains triumphs, wow!), I recognised Flashman on sight as the star of Hughes’ book. Fag-roasting rotter and poltroon he might be, he was nevertheless plainly box-office, for he had the looks, swagger and style (‘big and strong’, ‘a bluff, offhand manner’, and ‘considerable powers of being pleasant’, according to this creator) which never fail to cast a glamour on villainy. I suspect Hughes knew it, too, and got rid of him before he could take over the book – which loses all its spirit and zest once Flashy has made his disgraced and drunken exit.

[He was, by the way, a real person; this I learned only recently. A letter exists from one of Hughes’ Rugby contemporaries which is definite on the point, but tactfully does not identify him. I have sometimes speculated about one boy who was at Rugby in Hughes’ day, and who later became a distinguished soldier and something of a ruffian, but since I haven’t a shred of evidence to back up the speculation, I keep it to myself.]

What became of him after Rugby seemed to me an obvious question, which probably first occurred to me when I was about nine, and then waited thirty years for an answer. The Army, inevitably, and since Hughes had given me a starting-point by expelling him in the late 1830s, when Lord Cardigan was in full haw-haw, and the Afghan War was impending… just so. I began with no idea of where the story might take me, but with Victorian history to point the way, and that has been my method ever since: choose an incident or campaign, dig into every contemporary source available, letters, diaries, histories, reports, eye-witness, trivia (and fictions, which like the early Punch are mines of detail), find the milestones for Flashy to follow, more or less, get impatient to be writing, and turn him loose with the research incomplete, digging for it as I go and changing course as history dictates or fancy suggests.

In short, letting history do the work, with an eye open for the unexpected nuggets and coincidences that emerge in the mining process – for example, that the Cabinet were plastered when they took their final resolve on the Crimea, that Pinkerton the detective had been a trade union agitator in the very place where Flashman was stationed in the first book, that Kipling’s The Man Who Would Be King had a factual basis, or that Bismarck and Lola Montez were in London in the same week (of 1842, if memory serves, which it often doesn’t: whenever Flashman has been a subject on Mastermind I have invariably scored less than the contestants).

Visiting the scenes helps; I’d not have missed Little Big Horn, the Borneo jungle rivers, Bent’s Fort, or the scruffy, wonderful Gold Road to Samarkand, for anything. Seeking out is half the fun, which is one reason why I decline all offers of help with research (from America, mostly). But the main reason is that I’m a soloist, giving no hints beforehand, even to publishers, and permitting no editorial interference afterwards. It may be tripe, but it’s my tripe – and I do strongly urge authors to resist encroachments on their brain-children, and trust their own judgment rather than that of some zealous meddler with a diploma in creative punctuation who is just dying to get into the act.

One of the great rewards of writing about my old ruffian has been getting and answering letters, and marvelling at the kindness of readers who take the trouble to let me know they have enjoyed his adventures, or that he has cheered them up, or turned them to history. Sitting on the stairs at 4 a.m. talking to a group of students who have phoned from the American Midwest is as gratifying as learning from a university lecturer that he is using Flashman as a teaching aid. Even those who want to write the books for you, or complain that he’s a racist (of course he is; why should he be different from the rest of humanity?), or insist that he isn’t a coward at all, but just modest, and they’re in love with him, are compensated for by the stalwarts who’ve named pubs after him (in Monte Carlo, and somewhere in South Africa, I’m told), or have formed societies in his honour. They’re out there, believe me, the Gandamack Delopers of Oklahoma, and Rowbotham’s Mosstroopers, and the Royal Society of Upper Canada, with appropriate T-shirts.

I have discovered that when you create – or in my case, adopt and develop – a fictional character, and take him through a series of books, an odd thing happens. He assumes, in a strange way, a life of his own. I don’t mean that he takes you over; far from it, he tends to hive off on his own. At any rate, you find that you’re not just writing about him: you are becoming responsible for him. You’re not just his chronicler: you are also his manager, trainer, and public relations man. It’s your own fault – my own fault – for pretending that he’s real, for presenting his adventures as though they were his memoirs, putting him in historical situations, giving him foot-notes and appendices, and inviting the reader to accept him as a historical character. The result is that about half the letters I get treat him as though he were a person in his own right – of course, people who write to me know that he’s nothing of the sort – well, most of them realise it: I occasionally get indignant letters from people complaining that they can’t find him in the Army List or the D.N.B., but nearly all of them know he’s fiction, and when they pretend that he isn’t, they’re just playing the game. I started it, so I can’t complain.

When Hughes axed Flashman from Tom Brown’s Schooldays, brutally and suddenly (on page 170, if I remember rightly), it seemed a pretty callous act to abandon him with all his sins upon him, just at the stage of adolescence when a young fellow needs all the help and understanding he can get. So I adopted him, not from any charitable motives, but because I realised that there was good stuff in the lad, and that with proper care and guidance something could be made out of him.

And I have to say that with all his faults (what am I saying, because of his faults) young Flashy has justified the faith I showed in him. Over the years he and I have gone through several campaigns and assorted adventures, and I can say unhesitatingly that coward, scoundrel, toady, lecher and dissembler though he may be, he is a good man to go into the jungle with.

George MacDonald Fraser

Dedication

For the Mad White Woman of Papar River

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

How Did I Get the Idea of Flashman?

Dedication

Explanatory Note

Map

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Appendix I

Appendix II

Footnotes

Notes

About the Author

The FLASHMAN Papers: In chronological order

The FLASHMAN Papers: In order of publication

Also by George MacDonald Fraser

About the Publisher

EXPLANATORY NOTE

One of the most encouraging things about editing the first four volumes of the Flashman Papers has been the generous response from readers and students of history in many parts of the world. Since the discovery of Flashman’s remarkable manuscript in a Leicestershire saleroom in 1965, when it was realised that it was the hitherto-unsuspected autobiographical memoir of the notorious bully of Tom Brown’s Schooldays, letters have reached the editor from such diverse places as Ascension Island, a G.I. rest camp in Vietnam, university faculties and campuses in Britain and America, a modern caravanserai on the Khyber Pass road, a police-station cell in southern Australia, and many others.

What has been especially gratifying has been not only the interest in Flashman himself, but the close historical knowledge which correspondents have shown of the periods and incidents with which his memoirs have dealt so far – the first Afghan War, the solution of the Schleswig-Holstein Question (involving as it did Count Bismarck and Lola Montez), the Afro-American slave trade, and the Crimean War. Many have contributed interesting observations, and one or two have detected curious discrepancies in Flashman’s recollections which, regrettably, escaped his editor. A lady in Athens and a gentleman in Flint, Michigan, have pointed out that Flashman apparently saw the Duchess of Wellington at a London theatre some years after her death, and a letter on Foreign Office notepaper has remarked on his careless reference to a ‘British Ambassador’ in Washington in 1848, when in fact Her Majesty’s representative in the American capital held a less exalted diplomatic title. Such lapses are understandable, if not excusable, in a hard-living octogenarian.

Equally interesting have been such communications as those from a gentleman in New Orleans who claims to be Flashman’s illegitimate great-grandson (as the result of a liaison in a military hospital at Richmond, Va., during the U.S. Civil War), and from a British serving officer who asserts that his grandfather lent fifty dollars and a horse to Flashman during the same campaign; neither, apparently, was returned.

It is possible that these and other matters of interest will be resolved when the later papers are edited. The present volume deals with Flashman’s adventures in the Indian Mutiny, where he witnessed many of the dramatic moments of that terrible struggle, and encountered numerous Victorian celebrities – monarchs, statesmen, and generals among them. As in previous volumes, his narrative tallies closely with accepted historical fact, as well as furnishing much new information, and there has been little for his editor to do except correct his spelling, deplore his conduct, and provide the usual notes and appendices.

G.M.F.

They don’t often invite me to Balmoral nowadays, which is a blessing; those damned tartan carpets always put me off my food, to say nothing of the endless pictures of German royalty and that unspeakable statue of the Prince Consort standing knock-kneed in a kilt. King Teddy’s company is something I’d sooner avoid than not, anyway, for he’s no better than an upper-class hooligan. Of course, he’s been pretty leery of me for forty-odd years (ever since I misguided his youthful footsteps into an actress’s bed, in fact, and brought Papa Albert’s divine wrath down on his fat head) and when he finally wheezed his way on to the throne I gather he thought of dropping me altogether – said something about my being Falstaff to his Prince Hal. Falstaff, mark you – from a man with piggy eyes and a belly like a Conestoga wagon cover. Vile taste in cigars he has, too.

In the old Queen’s time, of course, I was at Balmoral a great deal. She always fancied me, from when she was a chit of a girl and pinned the Afghan medal on my manly breast, and after I had ridden herd on that same precious Teddy through the Tranby Croft affair and saved him from the worst consequences of his own folly, she couldn’t do enough for me. Each September after that, regular as clockwork, there would come a command for ‘dear General Flashman’ to take the train north to Kailyard Castle, and there would be my own room, with a bowl of late roses on the window-sill, and a bottle of brandy on the side-table with a discreet napkin over it – they knew my style. So I put up with it; she was all right, little Vicky, as long as you gave her your arm to lean on, and let her prattle on endlessly, and the rations were adequate. But even then, I never cottoned to the place. Not only, as I’ve said, was it furnished in a taste that would have offended the sensibilities of a nigger costermonger, it had the most awful Highland gloom about it – all drizzle and mist and draughts under the door and holy melancholy: even the billiard-room had a print on the wall of a dreadful ancient Scotch couple glowering devoutly. Praying, I don’t doubt, for me to be snookered.

But I think what really turns me against Balmoral in my old age is its memories. It was there that the Great Mutiny began for me, and on my rare excursions north nowadays there’s a point on the line where the rhythm of the wheels changes, and in my imagination they begin to sing: ‘Mera-Jhansi-denge-nay, mera-Jhansi-denge-nay’, over and over, and in a moment the years have dropped away, and I’m remembering how I first came to Balmoral half a century ago; aye, and what it led to – the stifling heat of the parade ground at Meerut with the fettering-hammers clanging; the bite of the muzzle of the nine-pounder jammed into my body and my own blood steaming on the sun-scorched iron; old Wheeler bawling hoarsely as the black cavalry sabres come thundering across the maidan towards our flimsy rampart (‘No surrender! One last volley, damn ’em, and aim at the horses!’); the burning bungalows, a skeleton hand in the dust, Colin Campbell scratching his grizzled head, the crimson stain spreading in the filthy water below Suttee Ghat, a huge glittering pile of silver and gold and jewels and ivory bigger than anything you’ve ever seen – and two great brown liquid eyes shadowed with kohl, a single pearl resting on the satin skin above them, open red lips trembling … and, blast him, here’s the station-master, beaming and knuckling his hat and starting me out of the only delightful part of that waking nightmare, with his cry of ‘Welcome back tae Deeside, Sir Harry! Here we are again, then!’