Полная версия:

The Twenty-Seventh City

The TWENTY-SEVENTH CITY

Jonathan Franzen

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2017

Copyright © Jonathan Franzen 1988

Cover design and illustration by Richard Bravery

Jonathan Franzen asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

The author is grateful for permission to quote the following copyrighted works: ‘The Red Wheel-Barrow’ from William Carlos Williams: Collected Poems 1909–1939, Volume I, copyright 1938. Reprinted by permission of Carcanet Press Limited. The ‘Chicken of the Sea’ jingle, reprinted by permission of Tri-Union Seafoods, LLC.

The author wishes to thank the Artists Foundation of Boston and the Massachusetts Council for the Arts and Humanities for their support in 1986

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9781841157481

Ebook Edition © November 2017 ISBN: 9780007383245

Version: 2017-11-27

Praise

‘A huge and masterly drama… gripping and surreal and overwhelmingly convincing’

Newsweek

‘Permeated with intelligence, beauty, and subversive humor, teeming with life, always on the edge of igniting from its own repressed energy… Franzen is an extravagantly talented writer’

Chicago Tribune

‘Franzen’s tour de force (to call it a “first novel” is to do it an injustice) is a sinister fun-house-mirror reflection of urban America in the 1980s… There’s a lot of reality out there. The Twenty-Seventh City, in its larger-than-life way, is a brave and exhilarating attempt to master it’

Seattle Times

‘Franzen goes for broke here – he’s out to expose the soul of a city and all the bloody details of the way we live… A book of range, pith, intelligence’

Vogue

‘Mr Franzen has talent to spare. His is a worthwhile entertainment, this picaresque tale the principal vagabond of which is its own sinuous plot’

Wall Street Journal

Dedication

To my parents

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

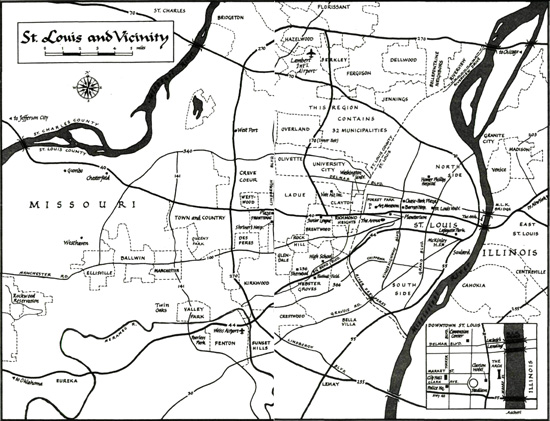

Map

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

This story is set in a year somewhat like 1984 and in a place very much like St. Louis. Many actual public achievements, policies and products have been attributed to various characters and groups; these should not be confused with any actual person or organization. The lives and opinions of the characters are entirely imaginary.

Map

1

In early June Chief William O’Connell of the St. Louis Police Department announced his retirement, and the Board of Police Commissioners, passing over the favored candidates of the city political establishment, the black community, the press, the Officers Association and the Missouri governor, selected a woman, formerly with the police in Bombay, India, to begin a five-year term as chief. The city was appalled, but the woman—one S. Jammu—assumed the post before anyone could stop her.

This was on August 1. On August 4, the Subcontinent again made the local news when the most eligible bachelor in St. Louis married a princess from Bombay. The groom was Sidney Hammaker, president of the Hammaker Brewing Company, the city’s flagship industry. The bride was rumored to be fabulously wealthy. Newspaper accounts of the wedding confirmed reports that she owned a diamond pendant insured for $11 million, and that she had brought a retinue of eighteen servants to staff the Hammaker estate in suburban Ladue. A fireworks display at the wedding reception rained cinders on lawns up to a mile away.

A week later the sightings began. An Indian family of ten was seen standing on a traffic island one block east of the Cervantes Convention Center. The women wore saris, the men dark business suits, the children gym shorts and T-shirts. All of them wore expressions of controlled annoyance.

By the beginning of September, scenes like this had become a fixture of daily life in the city. Indians were noticed lounging with no evident purpose on the skybridge between Dillard’s and the St. Louis Centre. They were observed spreading blankets in the art museum parking lot and preparing a hot lunch on a Primus stove, playing card games on the sidewalk in front of the National Bowling Hall of Fame, viewing houses for sale in Kirkwood and Sunset Hills, taking snapshots outside the Amtrak station downtown, and clustering around the raised hood of a Delta 88 stalled on the Forest Park Parkway. The children invariably appeared well behaved.

Early autumn was also the season of another, more familiar Eastern visitor to St. Louis, the Veiled Prophet of Khorassan. A group of businessmen had conjured up the Prophet in the nineteenth century to help raise funds for worthy causes. Each year He returned and incarnated Himself in a different leading citizen whose identity was always a closely guarded secret, and with His non-denominational mysteries He brought a playful glamour to the city. It had been written:

There on that throne, to which the blind belief Of millions rais’d him, sat the Prophet-Chief, The Great Mokanna. O’er his features bung The Veil, the Silver Veil, which he bad flung In mercy there, to bide from mortal sight His dazzling brow, till man could bear its light.

It rained only once in September, on the day of the Veiled Prophet Parade. Water streamed down the tuba bells in the marching bands, and trumpeters experienced difficulties with their embouchure. Pom-poms wilted, staining the girls’ hands with dye, which they smeared on their foreheads when they pushed back their hair. Several of the floats sank.

On the night of the Veiled Prophet Ball, the year’s premier society event, high winds knocked down power lines all over the city. In the Khorassan Room of the Chase-Park Plaza Hotel, the debbing had just concluded when the lights went out. Waiters rushed in with candelabras, and when the first of them were lit the ballroom filled with murmurs of surprise and consternation: the Prophet’s throne was empty.

On Kingshighway a black Ferrari 275 was speeding past the windowless supermarkets and fortified churches of the city’s north side. Observers might have glimpsed a snow-white robe behind the windshield, a crown on the passenger seat. The Prophet was driving to the airport. Parking in a fire lane, He dashed into the lobby of the Marriott Hotel.

“You got some kind of problem there?” a bellhop said.

“I’m the Veiled Prophet, twit.”

On the top floor of the hotel He stopped outside a door and knocked. The door was opened by a tall dark woman in a jogging suit. She was very pretty. She burst out laughing.

When the sky began to lighten, low in the east over southern Illinois, the birds were the first to know it. Along the riverfront and in all the downtown parks and plazas, the trees began to chirp and rustle. It was the first Monday morning in October. The birds downtown were waking up.

North of the business district, where the poorest people lived, an early morning breeze carried smells of used liquor and unnatural perspiration out of alleyways where nothing moved; a slamming door was heard for blocks around. In the railyards of the city’s central basin, amid the buzzing of faulty chargers and the sudden ghostly shiverings of Cyclone fences, men with flattops dozed in square-headed towers while rolling stock regrouped below them. Three-star hotels and private hospitals with an abject visibility occupied the higher ground. Farther west, the land grew hilly and healthier trees knit the settlements together, but this was not St. Louis anymore, it was suburb. On the south side there were rows upon rows of cubical brick houses where widows and widowers lay in beds and the blinds in the windows, lowered in a different era, would not be raised all day.

But no part of the city was deader than downtown. Here in the heart of St. Louis, in the lee of the whining all-night traffic on four expressways, was a wealth of parking spaces. Here sparrows bickered and pigeons ate. Here City Hall, a hip-roofed copy of the Hôtel de Ville in Paris, rose in two-dimensional splendor from a flat, vacant block. The air on Market Street, the central thoroughfare, was wholesome. On either side of it you could hear the birds both singly and in chorus—it was like a meadow. It was like a back yard.

The keeper of this peace had been awake all night on Clark Avenue, just south of City Hall. Chief Jammu, on the fifth floor of police headquarters, was opening the morning paper and spreading it out beneath her desk lamp. It was still dark in her office, and from the neck down, with her hunched, narrow shoulders and her bony knees in knee socks and her restless feet, the Chief looked for all the world like a schoolgirl who’d been cramming.

Her head was older. As she leaned over the newspaper, the lamplight picked out white strands in the silky black hair above her left ear. Like Indira Gandhi, who on this October morning was still alive and the prime minister of India, Jammu showed signs of asymmetric graying. She kept her hair just long enough to pin it up in back. She had a large forehead, a hooked and narrow nose, and wide lips that looked blood-starved, bluish. When she was rested, her dark eyes dominated her face, but this morning they were cloudy and crowded by pouches. Wrinkles cut the smooth skin around her mouth.

Turning a page of the Post-Dispatch she found what she wanted, a picture of her taken on a good day. She was smiling, her eyes engaging. The caption—Jammu: an eye to the personal—brought the same smile back. The accompanying article, by Joseph Feig, had run under the headline A NEW LEASE ON LIFE. She began to read.

Few people remember it now, but the name Jammu first appeared in American newspapers nearly a decade ago. The year was 1975. The Indian subcontinent was in turmoil following Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s suspension of civil rights and her crackdown on her political foes.

Amid conflicting, heavily censored reports, a strange story from the city of Bombay began to unfold in the Western press. The reports concerned an operation known as Project Poori, implemented by a police official named Jammu. In Bombay, it seemed, the police department had gone into the wholesale food business.

The operation sounded crazy then; it sounds hardly less crazy today. But now that a twist of fate has brought Jammu to St. Louis in the role of police chief, people here are asking themselves whether Project Poori was really so crazy after all.

In a recent interview in her spacious Clark Avenue office, Jammu spoke of the circumstances that led up to the project.

“Before Mrs. Gandhi dispensed with the constitution the country was like Gertrude’s Denmark—rotten to the core. But with the imposition of President’s Rule, we in law enforcement had our chance to do something about it. In Bombay alone we were locking up 1,500 lawbreakers a week and impounding 30 million rupees in illegal goods and cash. When we evaluated our efforts after two months, we realized we’d hardly made one speck of progress,” Jammu recalled.

President’s Rule devolves from a clause in the Indian constitution giving the central government sweeping powers in times of emergency. For this reason, the 19 months of such rule were referred to as the Emergency.

In 1975 a rupee was worth about ten U.S. cents.

“I was an assistant commissioner at the time,” Jammu said. “I suggested a different approach. Since threats and arrests weren’t working, why not try defeating corruption on its own terms?

“Why not enter a business ourselves and use our resources and influence to achieve a freer market? We chose an essential commodity: food,” she said.

It was thus that Project Poori was conceived. A poori is a deep-fried puff-bread, popular in India. By the end of 1975, Bombay was known to Western journalists as the one city in India where groceries were plentiful and the prices uninflated.

Naturally, attention centered on Jammu. Her handling of the operation, as detailed in the dailies and in Time and Newsweek, caught the imagination of police forces in this country. But certainly no one would have guessed that one day she would be in St. Louis wearing the Chief’s badge on her blouse and a department revolver on her hip.

Colonel Jammu, however, entering her third month in office, would have it seem the most natural thing in the world. “A good chief stresses personal involvement at all levels of the organization,” she said. “Carrying a revolver is one symbol of my commitment.

“Of course, it’s also an instrument of lethal force,” she continued, leaning back in her office chair.

Jammu’s frank, gutsy style of law-enforcement management has earned a reputation that is literally world-wide. When the search for a replacement for former Chief William O’Connell ended in its deadlock of opposing factions, Jammu’s name was among the first mentioned as a compromise candidate. And despite the fact that she had no previous law-enforcement experience in the U.S., the Police Board confirmed her appointment less than a week after she arrived in St. Louis for interviews.

To many here, it came as a surprise that this Indian woman met the citizenship requirements necessary for her job. But Jammu, who was born in Los Angeles and whose father was American, says she went to great lengths to preserve her citizenship. Since she was a child she has dreamed of settling in America.

“I’m terribly patriotic,” she said with a smile. “New residents, like myself, often are. I’m looking forward to spending many years in St. Louis. I’m here to stay.”

Jammu speaks with slightly British intonations and striking clarity of thought. With her fine features and delicate build, she could hardly be less like the stereotype of the gruff, male American police chief. But her record gives an altogether different impression.

Within five years of entering the Indian Police Service in 1969, she became a deputy to the Inspector-General of Police in Maharashtra Province. Five years later, at the astonishing age of 31, she was named Commissioner of the Bombay police. At 35, she is both the youngest police chief in modern St. Louis history and the first woman to hold the post.

Before joining the Indian police she received a B.A. in electrical science from the University of Srinagar in Kashmir. She also did three semesters of postgraduate work in economics at the University of Chicago.

“I’ve worked hard,” she said. “I’ve had plenty of luck, too. I doubt I’d have this job had I not received good press from Project Poori. But of course the real problem was always my sex. It wasn’t easy to buck five millennia of sexual discrimination.

“Until I became a superintendent I routinely dressed as a man,” Jammu reminisced.

Apparently, experiences like this played a key role in the Commissioners’ selection of Jammu. In a city still struggling to overcome its image as a “loser,” the Board’s unorthodox choice makes good public-relations sense. St. Louis is now the largest U.S. city to have a female police chief.

Nelson A. Nelson, president of the Board, believes St. Louis should take credit for its leading role in making city government accessible to women. “It’s affirmative action in the truest sense of the word,” he commented.

Jammu, however, appeared to discount the issue. “Yes, I’m a woman, all right,” she said with a smile.

As one of her primary goals, she names making city streets safer. While not offering to comment on the performances of past chiefs in this area, she did say that she was working closely with City Hall to devise a comprehensive plan for fighting street crime.

“The city needs a new lease on life, a fundamental shake-up. If we can get the business community and citizens’ groups to aid us—if we can make people see that this is a regional problem – I’m convinced that in a very short time we can make the streets safe again,” she said.

Chief Jammu is not afraid of making her ambitions known. One might venture to guess that she will meet with jealous opposition in whatever she attempts. But her accomplishments in India show her to be a formidable adversary, and a political figure well worth keeping an eye on.

“Project Poori is a good illustration,” she pointed out. “We applied a new set of terms to a situation that appeared hopeless. We set up bazaars outside every station house. It improved our public image, and it improved morale. For the first time in decades we had no trouble attracting well-qualified recruits. Indian police have a reputation for corruption and brutality which is largely due to the inability to recruit responsible, well-educated constables. Project Poori began to change things.”

Some of Jammu’s critics have voiced fears that a police chief accustomed to the more authoritarian atmosphere of India might be insensitive to civil-rights issues in St. Louis. Charles Grady, spokesman for the local chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, has gone even further, urging that Jammu be dismissed before a “constitutional disaster” occurs.

Jammu strenuously rejects these criticisms. “I’ve been quite surprised by the reactions of the liberal community here,” she said.

“Their concern arises, I believe, from an abiding distrust of the Third World in general. They overlook the fact that India’s system of government has been deeply influenced by Western ideals, particularly, of course, by the British. They fail to distinguish between the Indian police rank-and-file, and the national officer corps, of which I was a member.

“We were trained in the British tradition of civil service. Standards were extremely high. We were continually torn between sticking up for our troops and sticking up for our ideals. My critics overlook the fact that it was this very conflict which made a position in the United States attractive to me.

“In fact, what strikes me now about Project Poori is how American our approach was. Into a clogged and bankrupt economy we injected a harsh dose of free enterprise. Soon hoarders found their goods worth half of what they’d paid for them. Profiteers went begging for customers. On a small scale, we achieved a genuine Wirtschaftswunder,” Jammu recalled, referring to postwar Germany’s “economic miracle.”

Can she work similar wonders in St. Louis? Upon taking office, other chiefs in recent memory have stressed loyalty, training, and technical advances. Jammu sees the crucial factors as innovation, hard work, and confidence.

“For too long,” she said, “our officers have accepted the idea that their mission is merely to ensure that St. Louis deteriorates in the most orderly possible way.

“This has done wonders for morale,” she said sarcastically.

It was perhaps inevitable that many of the officers here, especially the older ones, would react to Jammu’s appointment with skepticism. But attitudes have already begun to change. The sentiment most often voiced in the precinct houses these days seems to be: “She’s OK.”

Five minutes into Joseph Feig’s interview, Jammu had smelled sweat from her underarms, a mildewy feral stink. Feig had a nose; he didn’t need a polygraph.

“Isn’t Jammu the name of a city in Kashmir?” he asked.

“It’s the capital during the winter.”

“I see.” He looked at her fixedly for several long seconds. Then he asked: “What’s it like switching countries like this in the middle of your life?”

“I’m terribly patriotic,” she said, with a smile. She was surprised he hadn’t pursued the question of her past. These profiles were a rite of passage in St. Louis, and Feig, a senior editor, was generally acknowledged to be the dean of local feature writing. When he first walked in the door, in his wrinkled tweed jacket and his week-old beard, fierce and gray, he’d looked so investigative that Jammu had actually blushed. She’d imagined the worst:

FEIG: Colonel Jammu, you claim you wanted to escape the violence of Indian society, the personal and caste conflicts, but the fact remains that you did spend fifteen years in the leadership of a force whose brutality is notorious. We aren’t stupid, Colonel. We’ve heard about India. The hammered elbows, the tooth extractions, the rifle rapes. The candles, the acid, the lathis, the cattle prods—

JAMMU: The mess was generally cleaned up before I got there.

FEIG: Colonel Jammu, given Mrs. Gandhi’s almost obsessive distrust of her subordinates and given your own central involvement in Project Poori, I have to wonder if you’re at all related to the Prime Minister. I don’t see how else a woman could have made commissioner, especially a woman with an American father—

JAMMU: It isn’t clear to me what difference it makes to St. Louis if I’m related to certain people in India.

But the article was in print now, definitive and unretractable. The windows of Jammu’s office were beginning to fill with light. She rested her chin on her hands and let the print below her wander out of focus. She was happy with the article but worried about Feig. How could someone so obviously intelligent be a mere transcriber of platitudes? It seemed impossible. Perhaps he was just paying out the rope, “giving” her an interview like a final cigarette at dawn, while behind her back he marshalled his facts into an efficient, deadly squad …

Her head was sinking towards her desk. She reached for the lamp switch and slumped, with a dry splash, onto the newspaper. She closed her eyes and immediately began to dream. In the dream, Joseph Feig was her father. He was interviewing her. He smiled as she spoke of her triumphs, the delicious aftertaste of lies that people fell for, the escape from airless India. In his eyes she read a sad, shared awareness of the world’s credulity. “You’re a scrappy girl,” he said. She leaned over her desk and nestled her head in the crook of her elbow, thinking: scrappy girl. Then she heard her interviewer tiptoe around behind her chair. She reached around to feel his leg, but her hands swung through empty air. His bristly face pushed aside her hair and brushed her neck. His tongue fell out of his mouth. Heavy, warm, doughlike, it lay against her skin.