скачать книгу бесплатно

A Cuppa Tea and an Aspirin

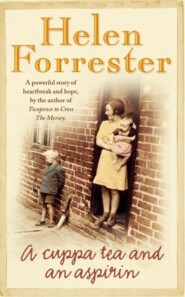

Helen Forrester

A powerful new novel, heart-breaking but ultimately uplifting, from the author of the classic Twopence to Cross The Mersey.Life in a Liverpool tenement block during the Great Depression is a grim struggle for Martha Connelly and her poverty-stricken family, as every day renews the threat of homelessness, hunger and disease.Family warmth remains constant however, despite the misery and disquiet of the slum surroundings, and the indomitible neighbourhood puts up a relentless fight for survival.Helen Forrester’s poignant novel relays bleakness and hardships, but celebrates also the spirit of unified hope and the restorative values of the close-knit community.

A Cuppa Tea and An Aspirin

Helen Forrester

Copyright (#ulink_06500289-b071-5ff4-9071-5decc901a4c5)

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2003

Copyright © Helen Forrester 2003

Helen Forrester asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007156948

Ebook Edition © AUGUST 2012 ISBN: 9780007387380

Version: 2014-12-10

For Vivien Green, with much gratitude

When the going gets tough,

the tough make tea

Anon

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#u32e5ba76-029e-5ec8-a1a8-d911a9faf302)

Title Page (#u2a4274f8-5a5a-5fd7-9ad9-d1f9e268db2b)

Copyright (#uba871049-23f7-587d-886d-bd5de3cab529)

Dedication (#u5fd57143-d4c0-5531-be5f-431d355bb34e)

Epigraph (#ucf908074-4946-5089-b031-f040942f987b)

AUTHOR’S NOTE (#u0ad7df46-f272-5d74-8cbb-345b2844b323)

PROLOGUE (#uc0d428fb-7256-51f7-bbd9-c746c4e05782)

ONE (#udf87837e-fa0f-5c75-a89f-aaab56b9695d)

TWO (#ufecb1b89-8744-54be-b317-821b0b3f193a)

THREE (#u81782d8f-58f2-5b9d-9035-f4d7c359814f)

FOUR (#uc6380bc4-d719-5872-9a94-2635970e8b1a)

FIVE (#uf31d644c-4abb-51ce-abf4-caa26764b12d)

SIX (#u757aa1e7-0da8-550e-8013-c2f9d325d0a6)

SEVEN (#u793d5a4c-4743-5dd9-8ab1-f16695fd7bc4)

EIGHT (#u033e9623-8aa6-5cc7-8b3c-ab8e3a0770bc)

NINE (#uec8bfdc2-5435-5805-9989-269573bd5f0c)

TEN (#u12ff0979-5b23-5726-98f6-b09cfeb412a1)

ELEVEN (#u8468b244-328d-53d4-876e-84fa32076d41)

TWELVE (#u19b176bb-4824-56b3-8630-a73132109e7c)

THIRTEEN (#ua8c32a3a-9911-57f6-b532-8cb9c4b005b6)

FOURTEEN (#u49c89133-0a24-579d-8eb8-fe8964633c79)

FIFTEEN (#udf466743-60df-54ff-9b35-f7ee25dcc2a4)

SIXTEEN (#u21e4518b-88c8-5274-bd8d-b821f1966891)

SEVENTEEN (#ue45439cb-c641-5bc5-9b1a-ac49f6289cbd)

EIGHTEEN (#u42389cb5-1c8b-548b-860b-57f420ddaf8c)

NINETEEN (#u90bda6b2-263e-52ac-b8d2-947fb619ee11)

TWENTY (#u8e738514-d031-5999-89b0-27fe33b6cea5)

TWENTY-ONE (#u179906b9-6af4-5cf8-9290-14852913347b)

TWENTY-TWO (#u1ec5c1b2-4f6d-52f0-bf95-8bbcb0067b84)

TWENTY-THREE (#u3347f853-c5b4-5a13-a687-02c1a56961a7)

TWENTY-FOUR (#u71203c0b-557f-5310-9e9e-2d6bc2a63e5e)

TWENTY-FIVE (#u3ef36989-92f0-53bc-a17e-88e1c1af372d)

TWENTY-SIX (#u94c1c3b3-f905-59a8-8e24-01a1fe40a6d2)

TWENTY-SEVEN (#uc975b0ba-38b9-56e8-8f30-574f8642c9be)

TWENTY-EIGHT (#u23158c7b-433c-5cc7-843c-de7c4a899489)

TWENTY-NINE (#ub12daada-cc31-51fb-aa82-28680c414292)

THIRTY (#u6f02d65e-eaac-5bfc-ad9f-101263f97057)

THIRTY-ONE (#u23d87677-f735-5fa7-ad87-b68566734e44)

THIRTY-TWO (#ubeb86297-54a0-553d-9147-0c0ead46fc7b)

THIRTY-THREE (#ucf3b438a-a542-59c7-bb2e-da9ae1b4ab7b)

THIRTY-FOUR (#u116c4246-b037-5555-87b6-216602808b36)

THIRTY-FIVE (#u0435cc20-3c67-5de5-8cad-efbff0f4803f)

THIRTY-SIX (#u59484fcf-b8b5-58d4-8a6f-dd0589f3665e)

THIRTY-SEVEN (#u5fad7c8d-b2f6-5f3a-a305-95710de651fd)

THIRTY-EIGHT (#u69640a30-5133-5672-942f-2971a60a2312)

THIRTY-NINE (#ufd68eafe-6c32-554d-aa42-d14d1a03a92a)

FORTY (#uf4c0163f-1566-58c1-94b4-680b92809d92)

FORTY-ONE (#ub90ded20-233b-51b3-a1b3-ce7167e49b41)

Keep Reading (#u13ef2dbb-a50f-543f-85dc-8423a8e4ec9d)

About the Author (#ubcc673ce-349c-5ac7-9aa8-b61f4bec2f2f)

Praise for Helen Forrester (#u4b1af97e-3b3b-570b-b9c6-29d4c4e0c256)

Also by the Author (#u729aadc4-c43b-5272-89cf-8387f1fd79ef)

About the Publisher (#u5803fa90-71be-5c00-979b-aa70bc3f38b2)

AUTHOR’S NOTE (#ulink_35a5575a-7c3f-5deb-90b5-59fb97fac4b7)

The author would like to thank sincerely her editors, Nick Sayers, Jane Barringer and Jennifer Parr for their support and sound advice while she was writing this book.

The book is a novel, not a history. Though the dreadful slums of Liverpool did exist, the care Home was a figment of the author’s imagination, as were the characters who lived or worked in these places; whatever similarity there may be of name, no reference is made or intended to any person living or dead, except for the well-known historical figure of Lee Jones and his wonderful work on behalf of the poor of the city which form a small part of the background of the book.

PROLOGUE (#ulink_1bf16b30-b6ef-513d-9841-9cc28b1faa0e)

‘I Look Proper Awful Without Me Gnashers’

1965

‘Angie! You mean you don’t know what a court is?’ In disapproval, the old woman’s lips pursed over toothless gums. She stared in genuine shock at the uniformed nursing aide who was slowly tucking in the sheets at the bottom of her bed. ‘Really, nowadays, you young folk don’t know nothing about nothing.’

‘It’s true, I really don’t know, Martha, unless you mean a magistrates’ court?’

‘Tush, I don’t mean a court up steps like that,’ retorted Martha irritably. ‘I mean a place where you live. Like a house.’

The aide smiled absently, her black face not unkind. She did not answer. Working in a crowded old folk’s Home, she was used to being scolded by the fifty-eight elderly, bedridden women and five equally incapacitated men, for whose daily care she was largely responsible; that is, being scolded by those who could speak. Some of them were the impotent victims of stroke, supposed to be turned every two hours and have their dirty nappies changed; and what a hopeless instruction that was: there simply wasn’t time. Its frequent omission accounted for the strong smell of old urine in the room and for the cries of misery from patients because of bedsores.

Opposite Martha’s bed, two women suffering from dementia were tethered to their beds. They chattered inconsequentially to themselves most of the day, their minds wandering – and God help me, thought Angie as she shook up Martha’s pillow, if they ever get loose: I’d be fired by Matron, sure as fate. Between the door and the dementia patients lay a victim of stroke, able only to grunt when she wanted anything.

In the bed next to Martha lay poor Pat, another bundle of helpless skin and bone. To Angie, the look of impending death was clear on her face, and she had already anxiously reported this to Matron. With a grim smile, Matron had assured the nervous aide that she was overreacting, as a result of her inexperience in nursing: the woman had seemed normal for her condition, when she had toured the ward two days before.

Angie had made no reply – she needed to keep her job. In her native Jamaica, rent by civil strife and surrounded by hunger and disease, she had seen so much of death. She certainly did not lack experience, she thought angrily.

For ten hours out of the twenty-four, all the patients were largely dependent upon Angie. Two other nursing aides, Dorothy and Freda, also from Jamaica, covered respectively the early morning and evening hours. A retired Irish nurse, Mrs Kelly, also working alone, cared for them from midnight to four in the morning, and there were many ignored complaints from patients at her inability to cope with their needs for bedpans or glasses of water.

The patients were either without family, or they were aged relatives of poverty-stricken local families who could not care for an invalid. Once they arrived in the nursing Home, Matron assumed that they were all uniformly permanently incapacitated. Some, like Martha Connolly, however, had suffered a broken hip or similar and might have hopes of being restored to health, if appropriately treated.

Matron was keen to retain patients like Martha, who, after the first few weeks, needed little care. Because they could do many things for themselves, they enabled her to keep her staffing costs low.

Uncouth, coarse Martha Connolly, Bed 3, Room 5, daughter of the Liverpool dockside, knew that she was not totally disabled. But she had had to agree with Matron’s sharp assessment that, if she tried to walk, she was liable to falls. She must, therefore, remain in bed unless an attendant was in the room to escort her.

Without any visitors, who might have spoken up on her behalf, unable to read or write, she knew herself to be stranded, just a numbered bed, her humanity forgotten.

Since all the aides were grossly overworked, she did not get much exercise. Her chart said that she was sixty, which was no great age. But her thin wispy hair was white, her back was humped and, at times, her mended hip hurt sharply. On the rare occasions when she was allowed out of bed, she had, until recently, used a stick. Her empty days dragged on from meal to meal, with nothing to alleviate their dreadful monotony.

‘Sometimes, I want to scream and scream,’ she once told Angie.

Angie smiled. ‘Well, don’t,’ she advised. ‘Matron might hear you. And she’d make you take a pill to quiet you.’

Fear crept up Martha’s back like pins and needles. The warning was justified. She had seen other patients drugged into silence.

One day, boiling with rage at Matron’s studied disregard of anything patients said to her, she had furiously brandished her walking stick at her. Matron hastily snatched it from her, and took it away to be safely stowed in her office. Since then, Martha had not had any exercise.