Полная версия:

A Forever Family

“I have to go.”

She edged out of his embrace.

“Shanna.”

“No,” she said firmly. “This shouldn’t have happened.”

Michael’s eyes narrowed. “Don’t deny it.”

“I’m not denying anything. I’m saying we are not doing this again. Ever.”

“Why?”

“Because we don’t fit, jive, dance, you name it.”

“Dance?”

“Compatibility, Mike. Admit it. We seldom agree. We live at opposite ends of the social scale. You’re my employer, and—” her voice rose on the last reason “—we don’t even like each other.”

“You don’t like me?”

“I like you,” she said, her heart sore. “Very much.” Too much.

Dear Reader,

We’re smack in the middle of summer, which can only mean long, lazy days at the beach. And do we have some fantastic books for you to bring along! We begin this month with a new continuity, only in Special Edition, called THE PARKS EMPIRE, a tale of secrets and lies, love and revenge. And Laurie Paige opens the series with Romancing the Enemy. A schoolteacher who wants to avenge herself against the man who ruined her family decides to move next door to the man’s son. But things don’t go exactly as planned, as she finds herself falling…for the enemy.

Stella Bagwell continues her MEN OF THE WEST miniseries with Her Texas Ranger, in which an officer who’s come home to investigate a murder fins complications in the form of the girl he loved in high school. Victoria Pade begins her NORTHBRIDGE NUPTIALS miniseries, revolving around a town famed for its weddings, with Babies in the Bargain. When a woman hoping to reunite with her estranged sister finds instead her widowed husband and her children, she winds up playing nanny to the whole crew. Can wife and mother be far behind? THE KENDRICKS OF CAMELOT by Christine Flynn concludes with Prodigal Prince Charming, in which a wealthy playboy tries to help a struggling caterer with her business and becomes much more than just her business partner in the process. Brand-new author Mary J. Forbes debuts with A Forever Family, featuring a single doctor dad and the woman he hires to work for him. And the men of the CHEROKEE ROSE miniseries by Janis Reams Hudson continues with The Other Brother, in which a woman who always contend her handsome neighbor as one of her best friends suddenly finds herself looking at him in a new light.

Happy reading! And come back next month for six new fabulous books, all from Silhouette Special Edition.

Gail Chasan

Senior Editor

A Forever Family

Mary J. Forbes

To Gary: You taught me to not only dream, but to believe. To Kristie and Ryan: Your faith in me is astounding. I love you all beyond comprehension.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

Thank you to Dr. Franky Mah for his expertise in emergency and medical care. Any errors are purely mine, not his. Also, a huge thank-you to Cindy Procter-King for hauling me up each time I fell and scraped my writing fingers.

MARY J. FORBES

grew up on a farm in Alberta amidst horses, cattle (Holsteins included), crisp hay and broad blue skies. As a child, she drew and wrote about her surroundings and in sixth grade composed her first story about a lame little pony. Since those days, she has worked as a reporter and photographer on a small-town newspaper and has written and published short fiction.

Today, Mary—a teacher by profession—lives in beautiful British Columbia with her husband and two children. A romantic by nature, she loves working along the ocean shoreline, sitting by the firs on snowy or rainy evenings and two-stepping around the dance floor to a good country song—all with her own real-life hero, of course.

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter One

He looked the way a man would, catching a woman’s scent.

Except he wasn’t a man, but a horse. A red stallion. One that had caught her scent. He raised his angular chin a notch, dark eyes skeptical, as she approached the long, narrow paddock.

His muscled quarter-horse haunches quivered. In arrogant defiance, he tossed his head.

Shanna McKay took another step toward him. Flee or charge, big fella?

She wasn’t afraid. And knew he sensed that.

Whatever it took, she wanted the horse’s owner to see she loved big, domestic animals. When her hand caressed the stallion’s coat, she wanted the owner to recognize her skill and knowledge.

Her steps slowed.

Manure, dust and cut clover tracked through the late June air. A fly whirred past her face. The stallion’s lips tightened, its ears flattened. He stood transfixed.

She held out a hand. “Hey, big boy.”

Nose lifting higher, his eyes widened.

“What the hell are you doing?”

At the thundering voice the stallion galloped away, its elegant sorrel head swinging side to side, its tail glinting in the westerly sun like a sheaf of prairie grain.

Shanna darted a look over her shoulder and considered high-tailing it across the pasture to join her equine partner. The man standing opposite the gate was not who she’d expected. All six-feet-plus of him in tailored dark trousers and linen shirt, he stared at her as if she’d called his mother a foul name.

“Oh.” She purged the instinct to set a hand to her throat the way Jane Eyre might have done with Mr. Rochester. “I didn’t hear you.”

“Obviously.” He opened the gate and stalked toward her. “What’re you doing rubbing noses with an animal you don’t know?”

“I was—” If the animal she’d surveyed moments ago had taken on a human persona, it would have been this man—from his dense, saddle-burnished hair to his spit-and-shine loafers. “I was introducing myself to him.”

“He bites.”

“It’s all right, I know horses.” This man couldn’t be the foreman, not dressed like that. Was he the M. Nelson from the newspaper ad?

“You know horses. Huh.” His chilled gray eyes cut to the stallion watching them from the middle of the small pasture, red-gold on jade-green. “You’re out of your league with him, miss.”

“Shanna. Shanna McKay. For what it’s worth, I’ve lived around horses most of my life.” She looked at him pointedly, considered her options and, as usual, tossed them aside. “I know to approach with caution and a soft voice the first time.”

The man’s eyes cut back to her. A small pock to the right of his upper lip whitened. “Are you saying I didn’t? For what it’s worth, Ms. McKay, I’m not completely ignorant when it comes to approaching stallions, or any horse for that matter.”

“Know what, I was about to leave. It was nice meeting you.” This particular job she did not need. There were others. Dammit, there had to be. Jobs where people were less abrasive and the money-men more congenial.

She stepped past him.

“Just a minute.” He blocked her path. “Why are you here?”

Ignoring his knife-edged cheekbones and grim jaw, she looked square into the steel of his eyes. “I came about the job advertised in the paper.”

The man blinked once, clear shock on his face. “You want to milk cows?”

If it meant keeping a roof over her brother’s head and money in his college fund. She hiked her chin. “I have experience.”

He scanned her body. “A little slip like you? Shoving around thousand-pound cows?” A soft chuckle. “I don’t think so.”

“I’m not a slip. I’m five eight and weigh—”

“One-twenty.”

Her turn to blink.

“I’m a doctor. I know the human body.”

He was…Michael Rowan? Top surgeon at Blue Springs General? Well, no doubt he knew the female body best of all, then. With that face, he probably had a different girlfriend every weekend.

“You need to eat more,” he continued, jerking her rumination off balance. “You’re at least fifteen pounds underweight.”

“Excuse me?” So she didn’t eat properly half the time. He didn’t know her life. Didn’t know she slogged every night at her accounting courses. Of her need for a career, a stable source of income. Dr. Michael Rowan knew nothing about her.

His eyes softened abruptly. “I apologize. Bad habit I have, giving unwanted medical advice. Need to curb that.” A tiny smile altered the line at the edge of his mouth.

She nodded. “Just tell me where I can find M. Nelson.” In minutes she’d be out of his hair, out of his life.

“She’s out of town.”

“Your foreman’s a woman?”

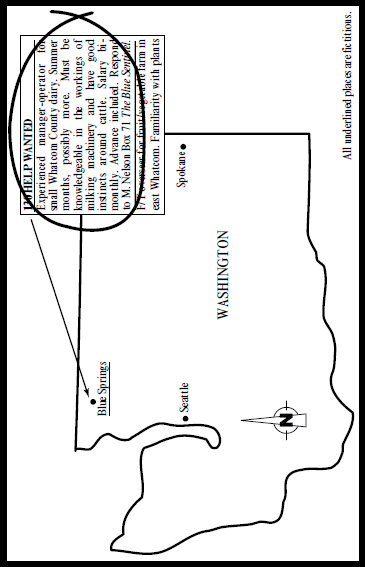

“No foreman. My grandmother.” In a placid state his eyes were dull silver. “A combination of family names as well as ownership. I didn’t want the clinic staff hounded with a bunch of calls.” He tilted his head, a pleat between his black brows. “You were to answer the ad through The Blue Sentinel.”

Her face warmed. She had wanted to impact with charm, wit and intelligence. Face-to-face. Michael Rowan, she saw, was not a man easily impacted. “Well,” she said. “I’m probably late, anyway.” The ad had run in three issues of the biweekly paper.

He studied the horse in the distance. “How’d you know it was Rowan Dairy?”

“Word gets around.”

Weariness marked his eyes as he studied her. Scraping his hands down stubbled cheeks, he released pent-up air. “Again, my apologies.” He held out a hand. “Michael Rowan.” His fingers wrapped around hers, warm and firm. His look wrapped around her heart, cool and steady. She let go.

“I know. We went to the same high school.” The way his eyebrows took flight had her lips twitching. “I was beginning middle school when you graduated.”

“McKay… The name’s familiar. Have you been to the clinic?”

“I don’t get sick.”

“Live around here, then?”

“In Blue Springs.”

“I see.” He tucked his hands into the pockets of his black dress pants and looked at her as if he could see beyond her skin, into her body. Into her.

She turned toward the knapsack sitting in the dirt by the gate. Hoisting the bag to her shoulder, she said, “I need this job, Doctor Rowan. Are you hiring?”

“That depends.”

“On?”

His hands came free of their pockets. Dust scuffed his shoes as he walked toward her. “On your expertise.”

“Four years, three months.”

He opened the gate, held it. She passed through. An efficient tug, a thunk of the wooden bar and it closed behind them. “Come up to the house,” he said. “Might as well get this over with, right now.”

“Over with?”

A sigh. “When you’re applying for a job, Ms. McKay, the employer—me—needs to ask some questions. But, I’m not doing it with horse dung on my shoes.”

A tobacco-brown smudge clung to the side of his left loafer. Rolling her lips inward, she looked to the pasture where the stallion grazed, picture-perfect in the distance. I’m not afraid of you. Or your famous owner.

“Ms. McKay. If it’s all the same to you, I’d like to eat tonight before I go to bed. I’ve had a long day.”

“Sorry,” she said. “I have a habit of—”

With a crisp turn, he strode off.

Daydreaming.

So much for conversation. She watched him go. Each cant of his succinct hips plied tiny creases into the fine, white shirt at his belt. He had those streamlined Tiger Woods buttocks. And long, long legs—which, at the moment, wolfed up ground.

The job, Shanna. You need the job. Remember that.

She hurried after him.

The trail wound through a hundred yards of spruce, cedar and birch. The trees blocked the barnyard from a two-story yellow farmhouse. Why hadn’t she noticed it before, this century-old Colonial—its tall windows and ample verandah strung with boxes of red and white geraniums overlooking paddock and pasture? No front lawn. Instead, a cornucopia of lush, leafy produce—beans, peas, onions, carrots, potatoes, squash and corn—fanned toward the pastures. Behind the house, the forested hill rose rapidly. She imagined its warm, emerald quilt of Douglas fir offered cozy vistas in bleaker seasons.

They crossed the driveway where the final rays of the day’s sun glossed a black Jeep Cherokee. Her dented two-toned silver pickup remained down at the barn where she’d parked it, drawn first to the farm’s animals instead of to its people.

The doctor walked down a flagstone path along the side of the house, to the rear door. There, from a cement stoop, he tossed his shoes to the grass. He held open the door. “Come in.”

Leaving her pack, she toed off her sandals and followed. The mudroom was neat and compact while the adjoining large, bright kitchen supported a greenhouse window she inherently loved.

The living section…

Oh, my.

A wood-beamed ceiling spanned a sunken room. Ebbing daylight spilled from wide, tall windows and warmed a bouquet of lemon oil. At the base of an oak staircase, hung a woman’s painted portrait. Her resolved, dark beauty emanated power.

“Ms. McKay?”

She jerked around. He stood in a small study, watching her. How long had he been waiting?

“Your home is lovely,” she told him, meaning it.

“Thank you.” He gestured to the den’s single leather chair. “Please. Sit down.”

From the rolltop desk he picked up a pen and a black notebook, then settled on the window seat, ankle on knee. Scribbling in the booklet, he waited until she eased onto the dough-soft seat where she kept her back straight, her feet planted, and her fingers loosely laced in her lap. She curbed the urge to touch the three staggered dream catchers swinging from her ears.

Confidence, Shanna.

“Where did you gain your dairy experience?”

“Lasser Farm.”

He nodded. “I know it.”

She imagined he did. The childless Lassers had called Washington’s Whatcom County home for twenty years. “I started working for Caleb and Estelle when I was fifteen.”

“You didn’t finish school?” He sounded a bit horrified.

She smiled. “Of course I graduated. My brother Jason and I boarded with the Lassers while my dad—”

She wanted to observe the doctor’s face. She knew why he’d offered her the chair. Shadows and light. He sat in the former, she sat in the latter.

“Yes?” he prompted.

“My dad was a saddle bronc rider. He followed the rodeo circuit.” Still does, like an old hound chasing rabbits in his sleep.

For a moment Michael Rowan remained silent, then he smiled, small and quick. It tempered the line of his jaw. Soothed his eyes. Doctor-to-patient kind, those eyes.

“Ah,” he said. “McKay. Of course. Your father assaulted an orderly a while back for making him go through a difficult therapeutic maneuver.”

No pity, Doctor. My father’s conduct no longer matters.

Liar.

She said, “Brent—my dad—cracked four ribs at the Cloverdale Rodeo up in British Columbia. The doctors ordered him not to ride that summer. He…he didn’t take it well.” True to form, he’d raved and cussed. Didn’t they know he’d lose six months of winnings? He was a cowboy, for Pete’s sake, a man tough as nails. A couple beat-up bones wouldn’t stop him, no sirree.

But in the end they had. At least for those six months.

She continued, “He, um, took a job with the Lassers.” Manna from heaven, when compared to the days—weeks—she and Jase had lived on stale cheese, chips and Krispy Kreme doughnuts. “Caleb developed angina that year and needed help.” Turned out the couple had helped her and Jase far more. Loving them on sight. Opening their home and hearts with grace and compassion. Raising them as Brent had not.

Dr. Rowan jotted notes. “How many cows were they milking?”

“Forty. Some years forty-five.”

“We have ninety-two. A small outfit compared to some, but…” He studied her face.

She squared her shoulders. “I can handle it.”

Again, he gave her a slow, visual once-over. A small burn flickered in her belly. She wanted to leave the chair, tell him to move the interview to the living room where she could read his dark, enigmatic eyes. Equal ground. Person to person. Aspirant to interviewer. Not this…this man-woman thing.

“How strong are you?”

“Beg pardon?”

“Can you lift a five-gallon bucket of oats?”

“Yes.”

When he made a point of studying her arms, her skin flashed with heat. She should have worn a long-sleeved blouse. Or a sweatshirt. What had she been thinking to pull on this silky white tank top and this flowery skirt? Hurry, that’s what. Hurry to look good. To impress the employer. To look professional.

Well, no amount of hurrying would get her wiry muscles or, for that matter, pretty feminine limbs. Sorry, Doctor. You’re stuck with these long, skinny ones.

Annoyed at her self-criticism and his scrutiny, she asked, “Do you think because I’m a woman I’m not suited for the job?”

His eyes whipped to hers. “It has nothing to do with you being a woman.”

Then why the fitness quiz? “I assure you, Doctor Rowan, I can handle a bucket of grain. And a few cud-chewers.”

Silence hung like a weight.

She stood. “Perhaps you should consider someone else.” A man. With gym muscles. “I’m sure you’ll be flooded with applicants before long.” There had to be other jobs. She’d spread her search city-wise. Out Bellingham way, if necessary.

“Please, sit down.”

“It’s all right. I understand your concern.”

“Please.”

A tight moment passed. With his face lifted, the window light refined the lines around his mouth. Within his beard shadow a tiny scar shot to focus. She wondered when he’d received it. She sat.

“Thank you,” he said.

Their eyes caught. In her womb she felt a little zing.

Thirty-one years, and no man had ever touched her deepest, secret refuge—a soft, vulnerable, misty-eyed place. Not her father, not her ex-husband Wade, not even Jase, her sweet-faced brother. Then along comes the good doctor—and he rattles its door on the first meeting. She looked away. “Who’s your milker now?”

“A fellow from Maple Falls. Think you might know him?”

She shook her head. “But cows are sensitive to their milker. If the person has a calm touch, they’ll produce their best. About eighty pounds a day per cow is a good standard.”

Dr. Rowan rubbed the back of his neck as though he’d dealt with myriad crises since dawn and job interviews were an annoying side note. “Ms. McKay, just for the record, I’m not interested in whether these animals produce. The man I hired after my sis—” He broke off, pulled in air. His hand trembled on the page. “The guy gave notice two weeks ago. Saturday’s his last day. You’re the first applicant with any decent experience.”

The first? She’d heard of the ad from Jason, who’d been scanning the Help Wanted section for mechanic work. After the ad’s third run, he’d read the blurb aloud. “Go for it, Shan. What’ve you got to lose?” What indeed?

“It’s been a while since I worked around livestock,” she explained now. “But you won’t get anyone more dedicated.”

“I’m sure. However, let’s get one thing straight. I don’t want you making demands on me about the cattle, or anything else. I don’t need you telling me how to handle them, coddle them, or…whatever. The place is for sale, which means before summer’s out I’m hoping to have the papers signed, sealed and delivered to another owner. In the meantime, all you need to do is milk those Holsteins. Clear?”

“Like spring water.”

Again, their eyes held. Again, the zing.

“Do you know gardening?” he asked.

“As in hoeing and weeding?”

“As in canning and freezing. You saw our vegetable patch. In five weeks or so it’ll need harvesting.”

August, the hottest time of the year. She’d be sure to buy a big-brimmed, straw hat. “Consider it done.”

“Thank you. There’ll be a bonus for the extra work.”

He pulled open a drawer near her knee and took out a checkbook. With his sleeves rolled to the elbow, she saw that his arms were solid, bread-brown, and stippled with hair. Like a farmer’s, not like those of a man feeling for lumps and tying off arteries.

With a flurry of slashes he wrote out a check. “You’ll need an advance to tide you over until payday which is bimonthly. Sunday will be your day off.”

She gaped at the amount. Far more than what she’d earned in a month as a bookkeeper for R/D Concrete before the layoffs. And in Blue Springs, R/D had been the company if one wanted sound work. The doctor must be desperate.

“It won’t bounce, if that’s what you’re wondering,” he said when she continued to stare at the money.

“I—” She swallowed, sat straighter. “I know that.”

“Good. There’s a retired farmer, Oliver Lloyd, who lives a couple miles down the road. He comes daily to clean the barns and tend to the cows and the land. We have roughly four hundred tillable acres in corn, oats, barley and alfalfa. He’ll assist you and milk on Sundays. When can you start?”

“Monday.”

“Fine. We begin at 4:30 a.m. Same time in the afternoon. Milking should take you no more than two hours tops. Any questions?”

With the salary he’d laid out? Unable to think, much less speak, she managed a “No.”

Without pause, he scribbled in the notebook. Thirty seconds passed. Forty.

Had she been dismissed? She read the check again. She should feel elated. She’d gotten the job. With a lucrative wage. For a few more months, Jason’s college fund and her night school accounting courses would stay intact.

So what was the problem?

Michael Rowan.

He intrigued, confused, and beguiled her into silly daydreams.

Get real, Shanna. The man wouldn’t look twice at you.

Staring at his bent head she unloosed a mental sigh. The logistics were as elemental as the points of a triangle. Point A: Their lifestyles—right down to his pen—were macrocosms apart. She observed the gold stylus flying across the page. Hardly a Bic special. Point B: Their natures didn’t concur. His reflected the Grinch while she, fool that she was, would give her right arm to safeguard and coddle the powerless, the tender-footed and the ugly. She shook her head.

Why couldn’t his grandmother be the one hiring?

Why couldn’t his face be broad and flat-boned?

His hair sparse and colorless?

He slapped shut the book, tossed it on the desk, and strode from the den. “That pickup down by the barn yours, Ms. McKay?”

She leapt after him. “Yes, I—”

A shrill bleep arrested his progress. She almost bumped into his back. He checked his pager. “I need to make a call. Wait here.” Back in the study, he closed the door with a quiet snick.

In the silence, the room lay at her feet: the tall windows, the tea set, the portrait of the woman.

What had she been thinking, Shanna wondered, envisioning herself in this house? It wasn’t her. Houses like this…

A glance at the closed study. Men like that…

Like Wade. Charming in face, honed in body. Women drooling with one look of his sinful eyes and one flash of his sexy smile.

Still, standing where she was, a sense of homecoming seeped into her blood, warm and favorable. She thought of Caleb and Estelle’s farmhouse where she’d spent most of her adolescence. Where she’d come to realize Brent—her father—would forever be a rodeo hound. Loving her and Jase, in his own skewed way, from miles down the road.