Полная версия:

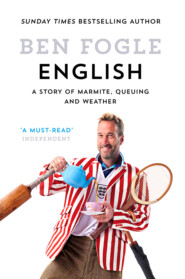

English: A Story of Marmite, Queuing and Weather

COPYRIGHT

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017

Text copyright © Ben Fogle 2017

Photographs © Individual copyright holders

Cover photograph © Simon Warren

Ben Fogle asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008222284

Ebook Edition © October 2017 ISBN: 9780008222260

Version: 2018-02-21

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

PROLOGUE

INTRODUCTION: LIVING ENGLISHLY

Chapter One: WHATEVER THE WEATHER

Chapter Two: THE SHIPPING FORECAST

Chapter Three: HEROIC FAILURES

Chapter Four: STRAWBERRIES AND CREAM

Chapter Five: MAD DOGS AND ENGLISHMEN

Chapter Six: WELLIES, WAX, BARBOURS AND BOWLERS

Chapter Seven: THE SILLY SEASON

Chapter Eight: OO-ER, MISSUS, IT’S LORD BUCKETHEAD

Chapter Nine: RAINING CATS AND DOGS

Chapter Ten: THE QUEEN’S SANDMAN AND SWANMAN

Chapter Eleven: I’M SORRY, I HAVEN’T A QUEUE

Chapter Twelve: GRUB

Chapter Thirteen: ENGLAND’S GREEN AND PLEASANT LANDS

Chapter Fourteen: THE WORD

Chapter Fifteen: TEA AND SYMPATHY

CONCLUSION

PICTURE SECTION

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

PROLOGUE

There was a hubbub of excited chatter as, clutching steaming cups of tea, the women gathered around a series of small tables to admire the spoils of war. The Great Yorkshire Show had just finished and the crochet, patchwork, flower arranging and cakes had all ‘come home’. There was a general chatter of approval. The room was decorated with bunting and it had the air of a village fete. This was Jam and Jerusalem.

I was in Harrogate, North Yorkshire, for the weekly gathering of the Spa Sweethearts Women’s Institute. The WI, as it is known, was formed in 1915 to revitalize communities and encourage women to produce food in the absence of their menfolk during the First World War. Since then it has grown to become the largest voluntary women’s organization in the UK, with more than six thousand groups and nearly a quarter of a million members.

The Queen herself is a member, and the WI, in my humble opinion, understands better than any other organization how the country works. Always polite, it has a reputation for no-nonsense, straight talking. The chairwoman of the WI’s public affairs committee, Marylyn Haines-Evans, recently said, ‘If the WI were a political party, we would be the party for common sense.’ If anyone understands the quixotic essence of Englishness, it is the ladies who attend these regional WI gatherings.

I chose the location carefully too. Popular with the English elite during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, during the Second World War, government offices were relocated from London to the North Yorkshire town and it was designated the stand-in capital should London fall during the war. It frequently wins the Britain in Bloom competition and has been voted one of the best places to live in the UK. It is what I would call a solid Yorkshire town. The combination of Harrogate and the WI is, I think, the perfect English ‘brew’.

I had come along to one of the WI’s evening gatherings to find out what Englishness means to them. Rather uncharacteristically, I was a little nervous as I walked to the stage in the small hall. I had brought my labrador, Storm along as an icebreaker and for some moral support, and together we made our way to the centre of the stage.

It was a relatively small gathering, perhaps fifty strong, but these women have solid values and in my mind they are the voice of England. Ignoring the jingoistic reverence that a national sporting event or royal occasion generates, I asked them what Englishness means.

‘The weather.’

‘Queuing.’ A lot of nodding heads.

‘Apologizing. We are always apologizing,’ stated another woman to a chorus of agreement.

‘Roses and gardens.’

‘Tea.’ This got the loudest endorsement.

‘Baking and cakes.’

‘The Queen.’

I asked them whether they would ever fly the St George’s Cross from their homes. There was an audible gasp, accompanied by a collective shaking of heads.

‘Why not?’ I wondered.

‘Because it has been hijacked by the extreme right,’ answered one woman.

‘It represents racism and xenophobia,’ added another.

‘We aren’t allowed to be English, we are British.’

I asked whether we should celebrate our national identity more like the Welsh, Scots and Northern Irish. To which the whole room nodded in approval, not in a jingoistic, nationalist kind of way, but in an understated, English kind of way. It was a genteel, considered discussion of the virtues of Englishness and the erosion of our national patriotism.

‘The Last Night of the Proms is as patriotic as we get,’ explained another member of the group, ‘but that patriotism is about the Union.’

Here England was speaking. We have a solid idea of what it is to be English, we have a grasp of some of the character traits of living Englishly, but we no longer celebrate that Englishness.

I asked if it was time to reclaim our national identity and take pride in being English. There was a round of applause.

‘Reclaim the celebration of Englishness for us, Ben.’

And that is what this book is about.

INTRODUCTION

LIVING ENGLISHLY

I am standing at the top of a vertiginous hill. When I say vertiginous, I mean the gradient is 1:1 in places, so steep you can’t stand up. A damp mizzle has descended on the valley, coating the grass in a greasy layer of moisture that has in turn soaked into the soil, turning it into an oily runway of mud.

It is the kind of mizzle that soaks you unknowingly. It has a stealthy ability to drench clothes, hair and skin before you have even noticed. Large drips of rain begin to fall from the peak of my flat cap, worn in a hopeless attempt to keep a low profile. My heart leaps and my stomach lurches as I take in the contours of the steep hill.

On this Spring Bank Holiday Monday, hundreds of people are streaming across the fields below, yomping along the narrow footpaths that bisect the fields. Next to me a German from Hamburg is busy fitting a mouth guard to his teeth, while a New Zealand rugby player is shoving shin pads down his long socks.

Along the brow of the hill, flagged by a simple plastic fence, are a further dozen nervous-looking faces from across the globe who have descended on this damp Gloucestershire hill for arguably one of the most famous eccentric sporting events in the world, the annual Cooper’s Hill Cheese Rolling. To paraphrase one social commentator, it involves ‘twenty young men chasing a cheese off a cliff and tumbling 200 yards to the bottom, where they are scraped up by paramedics and packed off to hospital’.

Which is about right. The steepness of the hill, combined with the undulations and the enthusiastic adrenalin of young men being cheered on by a crowd of thousands of spectators, leads to broken legs, arms, necks, ribs and even backs as a handful of brave souls chase a 9lb Double Gloucester cheese downhill at 70mph.

Why they started doing it, nobody really knows, although there are theories. The most colourful is that it has pagan origins. The start of the new year (spring) was celebrated by rolling burning brushwood down hills to represent rebirth and to encourage a good harvest. To enhance this the Master of Ceremonies also scattered buns, biscuits and sweets at the top of the hill. Cheese rolling is said to have developed from these rituals, although the earliest record of it dates back only to 1826.

During rationing during and after the Second World War a wooden cheese was used, with a small triangle of actual cheese inserted into a notch in the wood. In 1993, fifteen people were injured, four seriously, and in 2011, a crisis hit when the cheese rolling was cancelled after the local council decided to try to impose some order on this typically ramshackle English event. The council stipulated that the organizers should provide security, perimeter fencing to allow crowd control and spectator areas that would charge an entrance fee. The official competition was cancelled and the event went underground … which meant it continued as normal, but without any official organization, and with no ambulances.

Since then, the event has continued to grow, courtesy of a clandestine group of anonymous ‘organizers’, their identities shrouded in secrecy to avoid prosecution. Cooper’s Hill Cheese Rolling continues to attract thousands of spectators and dozens of competitors from all over the world.

And now I find myself on the top of the famous hill next to an assortment of adrenalin junkies, waiting to take part myself.

‘You gonna do it?’ smiles a young lad holding a beer.

‘Maybe,’ I shrug. ‘You?’

‘No way mate, I’m not mad,’ he smiles.

A couple of local men with a semi-official air and wearing white coats are milling around.

‘Are you an organizer?’ I ask a man busy organizing.

‘Nah,’ he replies with a smile, ‘no organizers here.’

Another man in a white coat is busy with a bag of cheeses, a slight giveaway as to his official status. ‘Are you an organizer?’ I ask.

‘No, mate,’ he replies as he unpacks the cheese.

‘You’re not going to race the cheese, are you?’ asks an athletic-looking woman.

I shrug my shoulders.

‘Well, I’m the only medic here,’ she replies with a slight look of concern.

Hundreds and thousands of people continue to envelop the hill, which is now thronging with people of all ages, here to witness the unofficial official cheese-rolling championships. It seems incredible that the event has seemingly been so well organized when there are no official organizers. Without structure, money or a committee, the event has somehow managed to corral spectators, crowd control and competitors. It is perhaps a fine reflection of Englishness that the entire event is so beautifully managed.

Back to the top of the hill and my heart is pounding as I wait for the count to begin, images of broken bones racing through my mind.

‘I broke my neck racing the cheese last year,’ smiles a young girl. ‘I can’t decide whether to race it again this year,’ she adds.

‘I’ll count to four,’ instructs the official-looking unofficial. ‘We will release the cheese on three, you run on four.’

I look around at the nervous faces beside me as people dig their heels into the slippery slope. The hill is so steep and the mud so ice-like that it is difficult not to let gravity take its course even while sitting. Every so often one of the competitors slides a couple of metres down the slope, before struggling back up.

Next to me is Chris, the multi-winning champion who is also a serving soldier. ‘Any secrets or advice?’ I ask nervously.

‘Just go for it. Commit to the cheese,’ he smiles, ‘and keep the body loose.’

So worried have the army been about his participation and likely injury that they urged him not to compete, even changing his shift to coincide with the morning of the event. But wild dogs wouldn’t keep Chris from competing in his beloved event. He is the joint world champion cheese-roller, winning two cheeses – an honour he carries with pride.

The huge round cheese – its edges encased in wood to protect it from breaking up as it bounces down the hill – is rolled one-handed into position next to me by another Unofficial in a white coat and bowler hat, clutching a beer in his other hand.

‘For Dutch courage,’ smiles a man wearing a luminous yellow jacket that bear the words ‘Fuck Health and Safety’, offering me a bottle of whisky. I take a swig and hold my breath.

‘One, two …’

‘Three.’ And with that the cheese begins to roll, picking up speed in microseconds.

‘Four …’ There is a slight delay and then my feet begin to turn.

I take one huge stride before the gooey mud takes over. My legs are swiped from under me and I land with a heavy thud on the mud, before picking up speed as gravity does her thing. There is no stopping me now as I struggle to regain my balance, but my bottom clings to the mud like a bobsled to the icy track, following the contours of a small water channel. All around me I am aware of tumbling legs as competitors cartwheel, slip and stride down the vertiginous slope. I hear the roar of the spectators as I momentarily regain my balance and take another stride before slipping forwards, head first through a patch of stinging nettles and then over a small hillock. I am fleetingly airborne before roly-polying sideways over my arm and back onto my bottom.

Once again I take to my feet as the hill begins to flatten out. And now I face one of the biggest dangers of all … the local rugby team.

They have traditionally been used to slow competitors down and prevent collisions with the crowd gathered at the bottom of the hill. For ‘slow down’ read ‘tackle to the ground’, often with low leg tackles. I have been warned about the rugby team and now, on my legs once again and out of control, I find myself hurtling towards two enormous rugger buggers.

‘It’s Fogle’ is the last thing I hear before four arms envelop the lower part of my body and I come to a grinding halt in a heap at the bottom of the hill.

I lie there in a daze for a moment before another hand hauls me to my feet. I am a muddy mess, my arms covered in long scratches and grazes, my legs in large stinging-nettle welts, but apart from a throbbing pain in my right arm, I am not only alive but appear to be intact. Which is more than can be said for my fellow competitors, one of whom lies prostrate and unconscious at the bottom of the slope as a small crowd of concerned Unofficials gather around.

I catch a glimpse of Chris parading the cheese in front of the gathered world media. The event will be beamed around the world, from the Today Show in America to the front page of Australian newspapers. Somehow I have survived the cheese rolling and lived to tell the tale.

In many ways, cheese rolling in all its glorious absurdity defines us as a nation. It is daft, eccentric and gloriously pointless. There is no particular reason to do it, but it has become a rich part of our heritage, though no one really knows how or even when. We love to laugh at it even though it can cause serious injury. It involves stubborn, stiff-lower-jawed participants happy to tumble head over heels through mud and nettles and risk their lives in a hapless and, let’s be honest, hopeless task to chase a cheese at 70mph.

It defies rhyme or reason. It isn’t sexy or cool or clever. It is muddy and hurty, but it has an essential ‘Englishness’ about it …

This book has been a little like a chameleon. It has changed and morphed as I have travelled the length and breadth of England. A bit like us when we dress for the English weather, this book has never been quite sure what clothes to put on. So, as part of my researches, I have walked the quicksands of Morecambe Bay with the Queen’s Guide and climbed Helvellyn with the Fell Top Assessor. I have chased cheeses down Gloucestershire hills and danced with Morris dancers in Rochester. I have been fortunate to walk the grounds of Buckingham Palace and to exercise the horses of the Royal Household Cavalry on their summer holiday in Norfolk. I have sat through rain-drenched hours of missed play at Wimbledon and squelched through the mud of Glastonbury. I have walked the corridors of No. 10 Downing Street with prime ministers and I have served tea at Betty’s Tea Room in Harrogate. Each one quintessentially English, but what do they say about us as a nation?

After all, to the outside world, we are British. I remember once flying to New York and at immigration faced the frankly terrifying border guards at JFK airport.

‘What is your nationality?’ he asked.

‘English,’ I replied.

‘You can’t be English,’ he answered flatly.

‘But I am,’ I continued foolishly.

‘You can be British, but there’s no such thing as being English,’ he scowled.

What’s more, English and Englishness have become so politically incorrect. The words have been hijacked by UKIP and the BNP, becoming something that many of us feel squeamish about. We are unsure if we are even allowed to call ourselves English. We are, of course British, a part of a unique union of nations that make up Great Britain. We are not English, although we may be Scottish or Welsh or Northern Irish.

More often than I can remember during the research for this book, I’ve been told that I’m British not English. ‘I’m writing a book about Englishness,’ I would explain; there would be a pause, a head tilt and then,

‘Don’t you mean Britishness?’

‘No,’ I’d reply, ‘I mean Englishness.’

‘I think you mean Britishness,’ they’d inevitably repeat, adding in a whisper, ‘Don’t forget the other nations.’

And when I went onto social media to ask people for ideas on what are our English traits, the most common reply was ‘Don’t you mean British traits?’, followed by a stream of abuse from Welsh, Scots and Northern Irish incensed that I could be so callous as to write a book exclusively about Englishness.

But this book is about Englishness – or, as I decided to describe it to myself, living Englishly.

I am no social scientist or historian. I have no academic credentials in ‘Englishness’; in fact the subject has already been tackled by people far more learned and academic than myself – both Jeremy Paxman and Kate Fox have written brilliantly about Englishness. But what I do have is a burning passion, a drive and, most importantly, a pride in my identity. I love to celebrate this identity in all its quirkiness.

Cheese rolling is a good example of a national trait that rather accurately describes the character of Englishness – eccentricity. The dictionary definitions are pretty concise: according to the Collins English Dictionary, ‘Eccentricity is unusual behaviour that other people consider strange.’ The Oxford English Dictionary, meanwhile, defines ‘eccentric’ as ‘(of a person or their behaviour) unconventional and slightly strange.’

And, like a moth to a light, I have long been attracted to eccentricity. The child of an actress, it is fair to say that I grew up around a fair amount of oddball behaviour. My mother would often meet me at the school gates wearing a wild wig, heavy make-up and with some new and unrecognizable accent as she immersed herself in whatever her current role happened to be.

My immediate reaction was one of embarrassment. Like many children, I wanted to be a sheep and follow the crowd. I didn’t want to be different, to stand out.

But as I became older I found myself drawn to the unusual. Strange places and people. I remember meeting the Englishwoman who ran Helga’s Folly in Sri Lanka, and who walked around wearing black lace escorted by a dozen Dalmatians; or the British spy living in the Costa Rican jungle with tales of tea with Colonel Gaddafi and riding in tanks with Saddam Hussein; or peculiar aristocrats like Lord Bath and his dozens of ‘wifelets’.

I found myself drawn to eccentric landscapes like Dungeness with its crazy, Daliesque architecture, or competing in an array of eccentric fixtures from the Brambles cricket match in the middle of the Solent to the World Stinging-Nettle Eating Championships.

Does that make me an eccentric? I don’t think so, but there is most certainly one within. The joy of eccentricity is that you don’t care. Look at the Fulfords, the aristocratic family made famous by Channel 4’s The Fu@£ing Fulfords for an example of really not giving a F@£k. I am pretty confident that I will eventually become a bow-tie-wearing eccentric surrounded by dozens of dogs. It really is only a matter of time.

Eccentricity aside, I consider myself a proud Englishman. I was born in Marylebone, London, the capital of England. I am a Land Rover-driving, Labrador-owning, Marmite-eating, tea-drinking, wax-jacketed, Queen-loving Englishman. And yet technically I’m not. I’m actually an imposter. My grandfather was Scottish and my father is Canadian. In all honesty, I am a mongrel. A mixed breed with no obvious authority to write a book about Englishness, And yet I have lived my life being described as the quintessential Englishman. Over time some of those traits and characteristics have perhaps become exaggerated. I blame travel. Despite my childhood adoption of a few Canadian pronunciations, my accent and dialect has changed according to my location. Believe it or not, I haven’t always sounded like this. Like what? you might ask. Well, for those who have never heard me talk, I am a little bit Posh. Correction. I’m not posh but I sound posh. RP – Received Pronunciation – is the official term. IT MEANS I PRO-NOUNCE EVERY WORD AND SYL-A-BYL CLEARLY.

The first changes to my accent came when I went to live in Ecuador, South America. For the first time, I became proud of my heritage. Subconsciously it was probably also an effort to distance myself from America and Americans. I lived with a beautiful family called the Salazars, and Mauro, my Ecuadorian ‘father’, was obsessed with all things English. ‘Tell me about hooligans?’ he would ask over a plate of beans and rice. ‘And what about the Queen?’ He was obsessed with Benny Hill and Oasis and Four Weddings and a Funeral.

He would spend hours quizzing me on the motherland, and I suppose I began subliminally to morph into a sort of Hugh Grant caricature. Several further years in Central and South America and I became fixated on my heritage, hoarding jars of Marmite and boxes of PG Tips. It was only when I returned to give a talk at my former school in Dorset that one of my teachers commented on the changes to my accent.

I genuinely believe that it is all the time away, overseas, exploring and adventuring that has given me time to think and explore my national identity. Sometimes, when you are too close to something, it is difficult to reflect honestly; often, we don’t like what we see.

Let’s be frank: England itself doesn’t have a glowing halo when it comes to colonial and imperial history. Indeed, we are rightly embarrassed by much of our past. And now we face turbulent times in which we, as the wider nation, have been forced to ask ourselves who we are. What began with an emotionally charged independence referendum for Scotland ended with Great Britain’s decision to leave the European Union. In the light of all of that, what does it mean to be English?