Полная версия:

John the Pupil

Dedication

for brother Mathew

Epigraph

Every point on the earth is the apex of a pyramid filled with the force of the heavens.

ROGER BACON, Opus Majus

He shall pass into strange countries: for he shall try good and evil among men.

Ecclesiasticus 39:5

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Note on the Text

The Chronicle of John the Pupil

Afterword

Notes

About the Author

Also by David Flusfeder

Copyright

About the Publisher

Note on the Text

A few remarks should be made here about the history of this unique manuscript.

I quote from Augustus Jessopp’s lecture ‘Village Life Six Hundred Years Ago’, first delivered to a notoriously uninterested audience in the Public Reading Room of the village of Tittleshall in Norfolk, and later collected in his The Coming of the Friars and Other Historical Essays (1885):

In the autumn of 1878, while on a visit at Rougham Hall, Norfolk, the seat of Mr. Charles North, my kind host drew my attention to some large boxes of manuscripts, which he told me nobody knew anything about, but which I was at liberty to ransack to my heart’s content. I at once dived into one of the boxes, and then spent half the night in examining some of its treasures.

The smaller strips of parchment or vellum – for the most part conveyances of land, and having seals attached – have been roughly bound together in volumes, each containing about one hundred documents, and arranged with some regard to chronology, the undated ones being collected into a volume by themselves. I think it almost certain that the arranging of the early charters in their rude covers was carried out before 1500 A.D., and I have a suspicion that they were grouped together by Sir William Yelverton, ‘the cursed Norfolk Justice’ of the Paston Letters, who inherited the estate from his mother in the first half of the fifteenth century.

They had lain forgotten until they came under my notice. Of this large mass of documents I had copied or abstracted scarcely more than five hundred, and I had not yet got beyond the year 1355. The court rolls, bailiffs’ accounts, and early leases, I had hardly looked at when this lecture was delivered.

It was in this last collection, which the genial eye of the schoolmaster-essayist-cleric Jessopp failed to apprehend, where the fragmented chronicle of John the Pupil lay buried.

Not until another generation after Jessopp were the first attempts made to piece the chronicle together. It is a great shame that the task did not fall to someone more skilled than the amateur antiquarian Gerald Lovelace, whose expertise did not match his enthusiasm. He succeeded in pasting the fragments together in double columns in some kind of chronological order but, robust as parchment is, many of the pages suffered in the process. He presented the ‘finished’ volume, whose translation he did not attempt, to the benefactress Celia (Cornwell) Bechstein. It has had an unlucky subsequent history, and here is not the place to detail or dwell on its misfortunes and depredations, the estate disputes, the book thieves, the fire at Chatham; until recently it had been stored, in harsh conditions, in a warehouse room in Ealing.

The text before you is a translation from a mixture of languages – primarily Latin, but also some Middle English, Old French, Italian, and Occitan, as well as Hebrew and Greek. Efforts have been made to preserve the spirit and voice of the original, at the expense, inevitably, of some of the literal meaning.

I have operated under etymological constraints, using only words that would have been known to John or are English cognates to his Latin ones. I may not use the word ‘succeed’, for example, other than to denote a sequence, because that is a secular, originally sixteenth-century term, which presumes to credit a favourable outcome to an individual’s capacities rather than to the divine will. A donkey’s ears cannot ‘flap’; our companions may not ‘embark’ or ‘struggle’ or use ‘effort’. When trying to find unanachronistic correlatives for John’s vocabulary, I have aimed not for the striking word or phrase, but the most apt and, in most cases, recognisable.

Where there are sections lost from the original manuscript, their absence has been marked by ellipses and blank space.

Most of the fragments follow an obvious chronology (helped by their author’s habit of dating each entry by reference to the saint to whom the day is dedicated). One of the harder parts of the editorial task has been to decide upon the arrangement of some of the others. The mistakes that have been made here are the editor-translator’s own: I am not a historian or a philologist, just a worker in language, whose path to John’s manuscript has been an unlikely one that need not interrupt the reader’s attention.

The original has now found a hospitable home in the library of a private collector, who commissioned this translation and provided me with a transcription of the original in the interest of making this extraordinary story available to its widest possible audience, and to whom unutterable thanks are due but hard to bestow, as he wishes to preserve his anonymity.

The Chronicle of John the Pupil

Being the reconstituted fragments of the account of the journey taken by John the Pupil and two companions, at the behest of the friar and magus Roger Bacon, from Oxford to Viterbo in A.D. 1267, carrying secret burden to His Holiness Clement IV, written by himself and detailing some of the difficulties and temptations endured along the way.

… and see your face on the roof of the friary. Sometimes you would cast your eye down at us and we would scatter. More often, the face would disappear as if it had never been there at all, as if you were something we had conjured to frighten ourselves with. He was a prisoner, it was said, convicted of monstrous crimes. He was mad, he fed on the flesh of children, he wiped his mouth with his beard after he had done feasting. He was in league with the Devil, he was the Devil, performing unnatural investigations. Sometimes we would hear inexplicable thunder from the tower, a few claimed to have seen lightning on clear sunny days. Once, by myself, grazing my father’s goats, I was touched by a rainbow, slowly turning, painting the field with brief marvellous colour.

As I got older, I would go there less often. The grass grew higher by that part of the Franciscans’ wall. Strange flowers bloomed. Animals refused to graze there.

Most of the commerce of our village, maybe all the commerce, was done with the friars. They bought our milk and cheese and mutton, we cut down trees to sell for firewood. Sometimes we would catch sight of their Minister walking to Oxford. We would see the friars at mass. They came to preach to us. And, when I was about nine years old, two of the friars came to our village and gathered the children in a circle by the pond. They asked us questions about numbers and words, they instructed us to wield their shapes, and gave us apples in exchange for the correct answers. At the end, I had by far the most apples.

The following day, they came for me. I had no part of the transaction. When it was done, my father seemed satisfied. I hope he got a good price for me.

And so began my education. In the tower at the top of the friary where, Master Roger, you have your seclusion and your books – twenty or more when I arrived, an immense library to which you proceeded to add, bought through means I never did discover. It was not just me at first in that room of books and instruments and crystal and glass, there were other boys lifted from villages who had also passed the apple test.

You taught us the trivium, the arts of grammar, rhetoric and dialectic, and the quadrivium, which are the arts of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and music.

You read Aristotle to us, so much Aristotle, the ways of the heavens and the beasts of the field, Aristotle on Categories, on Prior and Posterior Analytics, the Sophistical Refutations. And you read Porphyry to us, and Nicomachus of Gerasa, and John of Sacrobosco, and the Elements of Euclid and the Practical Geometry of Leonardo of Pisa because, Master Roger, you said geometry is the foremost instrument for the demonstration of theological truth as well as being necessary for the understanding of natural philosophy.

The class shrunk, boys were cast aside, sent back to their villages, or given occupations elsewhere in the friary. And we read Grosseteste on light and Boethius on music, and Ptolemy on Astronomy, and Aristotle again, on the Heavens and Meteorology, on Plants, on Metaphysics.

And we read Qusta ibn Luqa on the Difference between Soul and Spirit and Averroes on geometry, and the antique authors of Rome: Seneca on the passions, Ovid on the transformations. You had taught in Paris, you used your lecture notes from the time before you had become a friar, and the class further shrank, my companions were too dull, too slow, they could not compute, deduce, dispute to our Master’s satisfaction, no matter how loudly you read or how hard you drove your wisdom against their bodies and souls.

For your primary method of pedagogy was to beat the information into your students’ heads: Here are the examples, numbers 1, 2 and 3. What are the examples?– Beat! – What are the examples?! List them! – Good enough. Now what law do these examples illustrate and prove? – Beat! – What are the examples? – Yes. Now what laws do they illustrate? – Yes. Now again. And again.

Your other method was to offer a short description of a special case in nature. It was the pupil’s work to gather this new information into what he already had been taught, to offer up a law to account for this otherwise strange manifestation, and the craft would be to form an argument so fine that it would entice you, Master Roger, elsewhere now, unmindful, back into the dispute.

(And, in the schoolroom, when they thought they were unobserved and unheard, Brother Luke would maliciously lead his fellows in a recitation of the martyrdom of Saint Felix, the strict teacher whose pupils stabbed him to death with their pens.)

Elsewhere, I saw little of the friary and nothing of the world. The friars went out to the city to preach, while my work was to learn. And then there were just two of us, me and Daniel, whose understanding was just as nimble, perhaps even nimbler than my own, but had an impediment which sometimes kept the required answers hidden behind eyes that were too large for his body, and we were the last vessels for my Master’s knowledge. Occasionally, on the roof, constructing the apparatus for the burning mirror, I would see my former classmates and the novice friars below. I once saw Brother Andrew and Brother Bernard nursing a broken-winged starling, but my Master called me back before I could discover if their labours prospered. I attended prayers. Each day, before Vespers, I had an hour for myself when I would lie on my bed, and meditate, try to quench the triangles and squares that occupied my inner vision and fight the demons that grow so strong before daylight, and bring myself closer to the steps of Our Lord, and otherwhile try to remember how my life used to be.

In this way were my days sanctified. In this way did I give thanks to the God who made me and the Saviour who redeemed me.

• • •

My Master does not approve of the divisions of the seasons. My Master does not approve of many things or, indeed, people. He disapproves of Peter of Lombardy and Thomas Aquinas and Albertus Magnus and the translators of the Holy Scriptures who have incorporated so many errors into the sacred text. He disapproves of the Principals of our Order who have sacrificed the lamb of knowledge on the altar of temporal concerns. He disapproves of anyone who does not believe the evidence of his own eyes and takes no pains to celebrate the glory of creation by gathering knowledge to gain a closer apprehension of God’s work.

My Master holds the wisdom of his own teacher Robert Grosseteste to be above all others in the present age, but even he is not beyond reproach as in his acceptance of the division of the seasons into four, when it should be, rather, three, intervals of growth, equilibrium and decline. My Master also has proved that the calendar is wrong. By his calculations, one-hundred-and-one-thirtieth of a day is being lost every year, as our method of reckoning the passage of time loses pace with the rhythms of the stars.

• • •

And I would help him build his mirrors and lenses, my instruction would proceed, and he would beat out time and we would sing together, and the fallacious seasons passed, and the misreckoned years passed, and I was seventeen years old and the only one left in his classroom.

Saint Athanasius’s Day

Brother Andrew so dainty and girlish, Brother Bernard silent and large and phlegmatic, half-doltish. Brother Luke the reprobate, malicious and acting so freely, and somehow, his lightness, always escaping censure. Perhaps this is because he has the ear of the sacristan. Brother Daniel is the perpetual mark for Brother Luke. There is a quality about Brother Daniel that offends Brother Luke, and rouses his energies. Brother Daniel takes these attentions without complaint, as if they are his due. He humbly bears the weight of Brother Luke’s tricks.

At night I go to sleep listening to the murmur of this little herd of novices in the dormitory as they devise their wiles against Brother Daniel. They do not include Brothers Andrew or Bernard in their works. Brother Andrew would be their mark were it not for the greater offence that Brother Daniel causes them. Brother Bernard stands neither for nor against them. They regard him as a beast in the field, not quite man.

As for me, they do not dare to act directly. They whisper against me too, I hear them, on walks down to the refectory, to mass; but the fear of Master Roger’s mystery and power extends to me: just as in those days of living outside the walls, when we looked up to the friary tower to frighten ourselves and fear you and throw little stones that would not reach a quarter of the way to the roof, not daring to look over our shoulders as we ran away to the safety of our fathers’ world, in case we saw demons flying after us, they dislike me but they do not dare to assault me in case Master Roger’s power move itself against them.

• • •

You ask me to observe the world, and you are my world, so I shall begin with you.

Master Roger is well-made. His body is strong, putting to shame the constitutions of men half his age. His eyes are the colour of the sea on a stormy spring morning. His beard is grey. He credits his strength and vigour to his diet. The purpose, he says, in eating and drinking, is to satisfy the desires of nature, not to fill and empty the stomach. He has his own elixirs of rhubarb and black hellebore, which he pounds down to a paste and adds to his meat. And I have mine, justly accorded to my age and capacities. My Master says that if I observe the regimen he lays down I might live as long as the nature assumed from my parents might permit. It is only the corruption of my father and his fathers before him that limits the utmost term beyond which I may not pass.

Master Roger does not sleep in the dormitory. Master Roger does not take his meals with the rest of the friary. Master Roger appears at most services, space around him separating him from the rest of the Order, his voice sonorous, distinct, godly. The remainder of the time he is in his room at the top of the tower, performing his investigations.

Our lessons are fewer, now that he is working so hard on his Great Work. But still, towards the end of each day, he will test me on the knowledge that he has poured into me, and then add a little more. I must answer his questions about mathematics and music and grammar and rhetoric and optics, demonstrate the burning mirror he has made; and if my answers are not full and prompt, if my demonstration is not performed with his subtlety and skill, if I do not speak with as much insight and wit as if he were the respondent, he beats correction into my head.

Humbly, I observe myself. I am of smaller stature than my Master. My limbs are narrow and may not carry great loads. When I observe my own features they do not displease me, but they are not yet full. On occasion I am told by one of the older friars to walk with greater solemnity because my body, if not countermanded, tends to rise with every step.

I am the mirror he is constructing, to reflect him back to himself.

• • •

Our steps are directed by the Lord. I had no choice in this, nor should I have. Who is the man that can understand his own way? But all the same, in the order of our days, in the book of our hours, as I perform my spiritual exercises, my mind wanders. As Cassian has written, we try to bind the mind fast with chains and it slips away swifter than a snake.

Once, when I was very young, there was a traveller, a Frenchman, who visited the friary. He spoke of mountains and kings and far places and aroused my Master’s envy, but also his respect. He had visited Tartars and Saracens and travelled in carts pulled by giant dogs that had the ferocity of lions. The traveller’s skin had been burnt in eastern deserts; his right hand was missing two fingers. He made mention of other injuries but as his body and much of his head were covered by a dark cloak we could only conjecture what they might have been. When he spoke, some of his sentences fell away before finding their conclusion, and he looked silently past those assembled as if part of him were still dwelling in a far place.

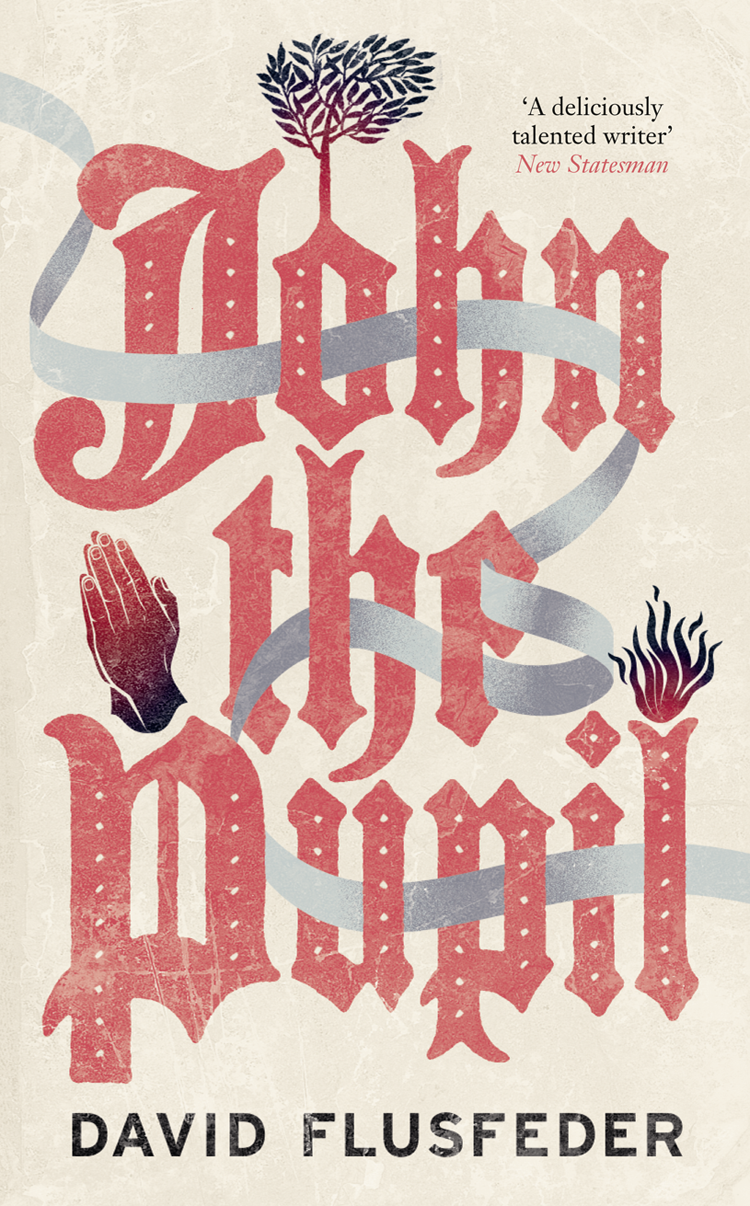

In front of me there is a map of the pilgrim way from Canterbury to Jerusalem by way of Rome. The journey does not signify an actual one, I know that. The purpose of this exercise is to lift the spirit into closer fellowship with Our Lord. Imagining myself on this pilgrim route, I walk towards the celestial city, stepping closer into the tread of the Redeemer as he laboured under the Cross.

It is in contemplation that the Christian finds the true Jerusalem.

Demons tempt me away. A demon of vanity drives me to demonstrate my own cleverness. Another demon pulls with his fingers at my cloak tugging me away from Our Lord, whispering to me about the false, earthly road.

I look into the rivers, the sea, the towers of the cities. I trace my fingers along the vellum and hope, forlornly, sinfully, for an actual journey, to take bodily steps along an actual road, a strange sun on my skin, dip my feet, not my fingers on ink, into a changing water.

The rivers and the sea are inscribed in azure. The writer who drew the map is at work most of the days, and nights, sleepless and secret, because my Master needs him for his Great Work. The map is unfinished. The imaginary pilgrim may not travel to the Holy Land because the map stops short of Rome. The sea disappears and the land becomes sky because the scribe suffers from a need to draw lines and curves with azure in the margins of my Master’s work.

I inscribe this on cuttings of parchment from my Master’s Great Work. At the end of the day, I sweep away the shreds from around the scribe’s desk and take what I require for my own work, a humble mockery of the true work. I do not think my Master begrudges me a little ink to make an account of my days.

Saint Abran’s Day

Once I knew how to herd goats, to fetch water without losing a drop, to make myself small against my father’s anger. Now I have become skilled in the art of gliding through the refectory and kitchen, to pick up bread, to lean over candlesticks and slice off small segments at the base of the candles, and on through the building, to the stairs, my arms folded, hands holding my spoils in the sleeves of my cloak. Our scribe needs food to eat and light to work by.

It is harder to gather wine and beer. When I descend into the cellar, to tiptoe past sleeping Brother Mark, to lift away two bottles, to make my return journey past the sleeping sentinel, to climb back up into the corridor by the dormitory, I am almost as anxious as I used to be, when I first followed Master Roger’s instruction to fetch food for the scribe. I know that it is not stealing, he explained to me that it is not, but still I shake, and pray. I must take two bottles, because when Brother Mark makes his accounting of the cellar, he touches each bottle in turn, chanting, sing-song, Here is master bottle and here is his wife, here is master bottle and here is his wife … His reckoning is done by remembering whether there was an even or an odd quantity of bottles on the previous day.

The scribe bemoans as he transcribes. He is being made to work too swiftly. It is the word, not its shape, that matters, Master Roger tells him, urging him on, Faster! Faster! I have written in the Book, in a rougher hand than the scribe’s, because Master Roger did not trust the scribe to draw Hebrew characters without understanding. Maybe, somewhere, a family is missing its father, a mother her son. The scribe shapes an azure line in the margin, he cannot help himself, a turn of thin colour that suggests the tip of a wave, a leafy branch of a tree. He sharpens his pen and wipes his face and looks around, as if for escape. There is none. He is here until the Book is finished or the world has ended.

Or if the Principal discovers what Master Roger is doing in his room. There is an Interdiction cruelly upon him. He may not write or debate or disseminate, other than sequestered in the friary classroom with his appointed pupil. The Order suspects him of novelties, which is an accusation hardly short of heresy. Yet he may exchange letters with friends and outside patrons of influence whom the Principal and even the Minister General should not seek to offend. Master Roger’s rooms are turned into a single industry. It is all done in the utmost secrecy. The Book is secret, which is maybe as it should be. In antique times, Master Aristotle composed a commentary to kingship, power and wisdom for his pupil Alexander of Macedonia. Master Roger’s Great Work is the true successor to Aristotle’s Secret of Secrets. Many evils follow the man who reveals secrets, wrote Aristotle. The planets align, the Principal vexes, Master Roger writes the words on wax tablets for transcription, the scribe cuts them into the page. I steal a wheel of cheese from the cellar and draw an imaginary journey before picking up my own pen.

We live in the Last Days. All things are temporary. The gates behind which Alexander enclosed Gog and Magog are falling. The horsemen are already abroad. In which case, I asked my Master, why should he, should we, make so many terrible labours to produce his Book? It is a work of majesty, indisputably, a magnificence of learning and opinion and ingenious device, which tells of the world and how it is viewed and the arc of the rainbow and the movements of the stars and of health and immortality and engines of war, all manners of things that would seem miraculous were they not founded on observation and deduction and Scripture, but, even if it is finished, even if it is somehow delivered and received by its intended Reader, would it not be for nothing? All things are known to the angels. They should not need to read it. And, as it has been written, the spread of learning will itself hasten the End Times. My Master hit me across the head with his Greek Grammar and commanded me to read and memorise the declensions of forty-nine nouns. It was as if I had accused him of vanity and pride, and maybe, thoughtlessly, I had.