Полная версия:

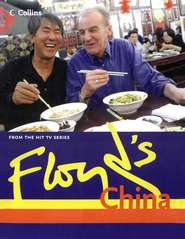

Floyd’s China

Floyd’s China

Keith Floyd

To Tess Floyd, and my ever-patient editor Barbara Dixon

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

Kissing don’t last, cooking do

Quantities

Soup

Chicken and Duck

Fish and Shellfish

Beef

Pork

Party Food

Noodles and Rice

Vegetables

Dips, Sauces and Accompaniments

To finish your meal

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

Next stop China!

It is a long haul from Heathrow to Beijing via Islamabad! And if you fly Pakistan International Airways, as I did, it is a very long, dry haul. There is, after all, only so much fruit juice you can drink and, of course, in common with all other airlines, you cannot smoke either, although I noticed, while I was on the flight deck with Captain Mian Naveed, his pipe was close at hand. I passed a couple of happy hours with him, a most amusing and philosophical gentleman.

I returned to my seat for dinner, served from a rickety old trolley, with wonderful dishes of Pakistani food – dhal, lamb korma, saffron rice, spinach and cottage cheese, delicious food – and when the steward noticed that I had, in fact, eaten everything including the bits of raw chilli in some of the dishes he said, ‘You like Pakistani food?’, ‘Yup’, I said, ‘I sure do.’ ‘Would you like some more?’ he said. ‘You bet,’ I said, and had second helpings. Instead of my usual alcoholic digestif to follow, I had a refreshing cup of green tea. Beijing, here I come!

Wow! What a swept-up airport there is in Beijing. Six o’clock in the morning and silence. Tick the boxes in my health immigration card. Pad gently through the long marble-floored corridors and climb gratefully into the limousine to take me to my hotel.

At the Crowne Plaza there is a reception committee. The general manager, the executive chef and several European acolytes are waiting to show me to my room. But, I don’t want to go to my room. I want some breakfast! And, by the way, I would quite like a drink of the non-fruit juice kind.

In the dining room’s kitchen, behind the long counters, there is the smiling face of a chubby head chef and, further along, serene ladies are wrapping up dim sums, but what I want is congee. They have four different varieties of congee for breakfast. But for those of you who don’t know what congee is, it is basically a porridge made from rice. Rice cooked in chicken stock. As simple as that, but by the time you have added pickled ginger, chillies, a couple of cooked prawns or some shredded chicken, you have a breakfast that can blast you into the stratosphere. After two bowls of congee, I returned to the buffet and my big, fat, smiling Chinese cook said, ‘What would you like next?’ So, I chose some spicy chicken with black beans and a plate of freshly boiled noodles garnished with crispy deep-fried onions, some ginger and pickled cucumber. When I say pickled cucumber, this is simply cucumber that has been marinated in rice vinegar. I helped myself to a large spoon of fresh chilli sauce – again very simple, chillies chopped up in oil. I was beginning to feel better after my nearly 48-hour journey (because I had overnighted in Islamabad), so I returned again to the buffet and got myself a plate of stir-fried pak choi, melon, green peppers and ginger. It was 7.30 a.m. but I noticed there was a Japanese section at the other end of this wonderful open kitchen, so I had a couple of bowls of clear chicken broth and some raw tuna fish with wasabi and pickled ginger. It was now 8.30 a.m. and, whereas time and tide wait for no man, it was time for a kip.

I took the lift to my room, switched on the television and, to my horror, Star Asia was showing Floyd on Fish, a programme I had made over 20 years ago. I opened the mini bar, selected a stiff one and went to sleep.

Refreshed, showered and altogether more up together, I discovered it was lunchtime. My chubby Chinese cook was still there, smiling, happy, and remembered me from breakfast. He had a crispy roast duck and carved it neatly for me, suggesting I take some steamed rice and pickles. And then, to my delight, when I wandered up to the bit where they have the puddings, there was a pot or dish of baked apple custard. Now, this surprised me, because I felt, or I thought I knew, the Chinese had no particular lactic cuisine, but was it good! And next to that were some very simple apple fritters sprinkled with cinnamon. God, I was feeling better!

My assistant, who comes unashamedly from Cumbria, chose the European option for lunch. Why do people travel thousands of miles to eat lasagne and chips that the Old Bull and Bush serves every lunchtime? I just got myself a few more fritters and waited to meet my photographer, who turned out to be an elegant, tall, Chinese-speaking German who had fallen in love with China many years before and now based her life and career in the People’s Republic. She said she wanted to be called Kat. She was probably 30 and had proposed that our first shoot should be on the Great Wall of China. So, the following morning at 5.00 a.m. we set off in a little red car driven by Mr Jing to the Great Wall at Mutianyu. This particular entrance to the Great Wall is the most grotesque tourist-orientated place you can imagine. People hollering, T-shirts for sale, worse than Brighton Pier; and even after you have taken the cable car up to the first level, you still have the steps to climb, created presumably by some Mongolian or Chinese emperor, which are each about three feet high. I find myself having to climb the final steps on my hands and knees, I could not do it, and yet the Saga louts with their walking sticks and rucksacks were springing up like newborn monkeys. Believe you me, if anyone says ‘take a trip to the Great Wall’ don’t bother. It is reconstructed, of course, it is magnificent, but when you get knocked over by hoardes of Swedes, Americans, Germans, Japanese, etc., all clutching their T-shirts, the mystique somehow disappears. The only sane man that day was Mr Jing, who, when we arrived at the barrier of the car park, which would have forced me to have walked another 200 metres, refused to be kowtowed and said, ‘I am taking Mr Floyd to the closest point possible!’ If you ever find yourself in Beijing (once know as, Peking and before that Ping Pong), call up Mr Jing. Without Mr Jing, life would be as for Bertie Wooster without Jeeves!

The morning had been cold, but now it was hot and overcast and in the hot wind it was snowing little puffballs of blossom as we bounced along in Mr Jing’s uncomfortable, hot, cramped car, smoking Mr Jing’s Chinese cigarettes. It had taken us three hours to get to the Great Wall instead of the estimated one hour. Jet lag and the early morning start were weighing heavily upon me as we headed back to Beijing. Mr Jing, with his trousers rolled up to his knees, was chattering away and, from time to time, poured some warm tea from a screw-top jam jar and handed it to me. Apparently all Beijing drivers carry endless quantities of tea in their cars and also endless packets of cigarettes, but then tea drinking is a cult in China. There are three kinds: fermented (red/black), unfermented (green) and semi-fermented (Oolong). Then there are the smoked teas, the scented teas and chrysanthemum tea. The flavours can vary enormously depending on which province the tea has been grown in and each has its own subtle fragrance. Tea is drunk all day and is considered good for just about anything that ails you; and by the way, it’s also still sold in bricks in China. But I digress. Anyway, we pulled over to the side of the road where there was a stall selling nuts and fruits and we were greeted, to my surprise, by a diminutive, elderly lady in a brightly coloured frock who led us across the road, chattering comfortably with Mr Jing and with the photographer, and into her one-storey, brick-built, shabby little bungalow. The garden had a rudimentary chicken coop and there were stacks of dried maize stalks, piles of nappa cabbage and a few tomatoes, but it was neglected and somehow rather sad. We went into the cool, gloomy house, illuminated by two flickering lightbulbs without shades, one in the kitchen and one in the other room. To the left and right of the kitchen door were two stone-built rectangles, each one containing an iron built-in dish about three feet in diameter. These were wood-fired, or maize stalk-fired, woks, that indispensable cooking utensil in China. We went into the other room, which had two chairs, a large built-in wooden bed about eight feet long, a bucket of water, a small table and shabby walls covered with garish photographs of Chairman Mao. Mrs Li’s husband (Mr Yang) sat, serene but smiling in his blue overalls. He was probably seventy. I didn’t know what was going on and I know not to ask. When something good happens, let it happen. There were three or four ladies in the cramped room and in a battered aluminium bowl they mixed flour and water into a dough, rolled it out very thinly and then cut it deftly into circles about three inches in diameter. Meanwhile, the old man, bent, slowly collected maize stalks from the garden and lit a fire under one of the huge woks. While he did this, the ladies chopped wild, green vegetables for which I have no translation – perhaps wild spinach or lovage, and other herbs; they added a little rice vinegar to this mixture and deftly, so deftly, rolled them into balls the size of a marble, folded them into the little rounds of dough and formed them into crescent shapes. After the smoke had settled, the water in the wok began to boil and one by one they dropped these wonderful dumplings into the water. After ten or fifteen minutes they were cooked and we all sat upon this built-in bed with a narrow plank of wood on stubby legs between us and ate these amazing dumplings.

They showed me the crude cellar in the garden, where, in former times, they had kept their cabbages and potatoes for use during the winter. They made green tea, talked and smiled and urged me to eat more. They had no money, barely any kind of a pension, but they had a dignity and a kindness that was most moving. Outside on the sill of the window, which in common with houses built at that time had no glass, just a kind of paper tissue, there lay drying in the sun a pile of orange peel, crisp like a poppadom, which they infused in boiling water and used as a remedy for colds, tummy upsets and as a general cure-all.

We shook hands, we hugged and said goodbye and bounced off down the congested road back to town, but again Mr Jing stopped, this time at a place the size of a European garden centre, next to a large plot of exquisite pottery – dragons, urns, pots, fish, warriors. There was nothing growing on the floor of the place that brought to mind a garden centre, but the sky was fluttering, clacking, flicking and swooping with hundreds of magnificent kites. They were purple, vermillion, orange, ochre, green, and red and on the ground there were row upon row of these multi-coloured kites in the shapes of hawks, eagles, fish and dragons. I bought two kites, each one with a wingspan of about eight feet, and Mr Jing made the staff fly them for me to see that they were right. They reeled them in on a large hand-held fishing reel and Mr Jing handled the transaction and, my God, he drives a hard bargain. These two exquisite flying creatures, because creatures they are, cost me the princely sum of three pounds! They are fragile and fine and I managed to get them back to France, undamaged and unbroken.

We made good progress towards Beijing until we hit the city. The traffic is horrendous, on four- or five-laned highways that cross the city of multi-storey buildings. Gotham City. Finally, we made it to a quiet parking lot and into an elegant, minimalist, glass-fronted restaurant called Din Tai Fung, allegedly Beijing’s finest dim sum restaurant. Dim sums, both sweet and savoury, were in former times served in tea houses so that businessmen, artists, philosophers and poets could sip tea and have a light snack while they discussed the day’s affairs. I suppose it was the Chinese version of an early English coffee house or a proper French cafe. The kitchen was screened by glass and you could see the sixteen or seventeen cooks working deftly, but it was surreal. I had hoped to enter the kitchen myself to observe very closely what they were doing, but I was not granted permission. They were clad in immaculate white uniforms, white, anklelength rubber boots, thin, white rubber gloves, crisp paper hats and masks. The fear of SARS still lingers. We ate some dim sum, drank some tea, took as many pictures as time would allow and worked out the recipes as best we could – many Chinese are very reluctant to reveal their culinary secrets to you. However, that did not stop me from finding out because I had Mr Jing.

By 9.30 p.m. I was back at the hotel, tired, elated, exhilarated and anxious for an early night. We had after all started at 5.00 a.m., but unfortunately, as I walked into the, if you like, Chinese brasserie of the hotel I was recognized and hijacked by a multi-national team that was there sponsoring the Johnny Walker Golf Tournament. Later I had some steamed sea bass with ginger, some plain boiled rice and a bowl of fresh fruit and then happily took the lift to my room on the fifth floor. I lay on the bed and continued to read Patrick O’Brian’s Desolation Island and minutes later the phone rang and it was 5.00 a.m. again!

I had read in the hotel’s brochure that a good way to enjoy Beijing would be to hire a bicycle and ride around: that must have been written in about 1954. It is utter bollocks, there is no way you can safely ride around the congested streets of this city. But, I had some lamb curry and some noodles, just quickly boiled with fresh greens thrown in, and set off anyway around the streets looking for what people ate for breakfast. Everybody seems to eat steamed buns, a bit like a dumpling with a little tiny bit of slightly sweet meat inside, or a deep-fried ‘youtiao’, a sort of long doughnut made from rice flour and water that costs ha’pennies. Others would go into little restaurants and have a bowl of noodles or a bowl of soup.

I chanced upon one really amazing street vendor. He had a large circular plancha, about two and a half feet in diameter, which was mounted above a charcoal fire on a spindle so he could spin this wheel around. He would spin it, pour a ladleful of his maize flour pancake mix onto it and all the while the wheel was turning he would scrape it out and scrape it out until he had a thin disk of a pancake about two feet in diameter. He flipped it over to his wife who filled it with finely chopped salad, coriander and chillies and folded it into a manageable envelope. It was outstanding.

On we went to the central market: sacks of chillies, dried fungus, dried mushrooms, mountains of Chinese greens, tank upon tank of live fish, frogs, snakes, turtles, mountains of pigs’ ears, pigs’ trotters, pigs’ intestines, pigs’ hearts, fat, plump ducks, chickens, chicken feet, chicken necks, chicken wings, pigs’ tails, ox tails, beef tripe, pork chitterlings, hearts, kidneys, lights. For me it was better than the finest art gallery, but I am sure many from the West would have found it unacceptable.

Then the fish section. Mountains of oysters, clams, snails, winkles, sea slugs, sea urchins. It was hot, the floor was awash in water, trampled leaves and crushed entrails. The pervading smell was slightly stomach turning, a long way from the clinical aisles of a Western supermarket. But I loved it. And I managed to buy my tinned, coppered steamboat, a sort of a charcoal-fired fondue set in which you heat stock and cook shrimps and vermicelli noodles, prawns and thin slivers of beef or chicken, greens and mushrooms.

It went on like this relentlessly for days as I left Beijing and toured the surrounding countryside. I cooked in kitchens and made stir-frys over the blasting fire of their cookers, which could propel a 747 into the stratosphere. These cookers are, of course, the secret of Chinese cookery. They are so powerful that everything cooks extremely quickly, literally in seconds, and you have to be sharp, you have to be swift and stay completely calm in this volcanic, gastronomic atmosphere. Whoever said the Americans invented fast food? Their version may be fast but it ain’t what I call food.

Of course, in some of the kitchens that they smilingly, and laughingly, let me into, I just couldn’t cope. I couldn’t roll out a four-foot rectangle of noodle dough then throw it up into the air, rather like a man clapping hands, and turn it within seconds into millimetre-thin lengths of noodle. That is an art, but an art that is taken for granted.

Back in Beijing I had to go to Tiananmen Square, I had to go to the Forbidden City, but I’m sorry, I am a cook, not a tourist, and Tiananmen Square may be the biggest in the world, but I am afraid I was very disappointed to discover it is just a square. No jugglers, no dragons, no clowns and no street food hawkers, just a man in sandals, jeans and a T-shirt who tried to arrest me as I attempted to have my picture taken with one of the guards. Despite its outrageous opulence and the massive building project and the obsessive preparations for the Olympics in 2008 and despite the utterly charming nature of the Chinese people, you cannot help feeling the sinister undertones of an authoritarian regime. Yeah, I looked at a few temples and went to the weird night food market – hundreds of stalls, all of them red and white, all of them staffed by proprietors all dressed in red and white as if they worked for Kentucky Fried Chicken. The array of food was a little different, however. Grilled snakes, crispy snakeskin, deep-fried locusts or some other large insect, all kinds of intestines alongside nice kebabs and vegetables, but I bailed out of that and went to Steamboat Street. Well, I called it Steamboat Street because all the restaurants there have steamboats. Not like the handmade steamboat I bought to impress my friends back in Europe, but here the steamboat, which is a metal bowl, is set into the table that you sit at, with a gas burner underneath it. They bring you a menu with a list of probably a thousand vegetables, meats, mushrooms, insects, fish, frogs, everything you can possibly imagine, or not imagine. All kinds of vermicelli, egg noodles, rice noodles. They pour some either mild or hot, depending on your taste, stock into the bowl, set fire to the gas and you just drop a few bits of food at a time into the stock, fish them out with a little wire basket and have an outstanding feast. The beef they bring you is sliced as thin as the thinnest Parma ham, so, of course, all these things cook in seconds, but you can take hours to eat it. Take good friends with you. My assistant from Cumbria, may God long preserve him, was again really thinking about a nice lasagne and chips and somehow failed to share my enthusiasm.

If Beijing has an equivalent of Langan’s Brasserie, Simpson’s in the Strand, The Ivy or the Rib Room at the Carlton Towers, then it has to be a restaurant called Old Beijing Zhajiang Noodle King at 29 Chong Wai Street, Chong Wen District, Beijing. There is one difference, however, and it is a big one. This stylish, long-established, noisy, clattering, garrulous rendezvous of the Guccishoed, Rolex-wearing, mobile phone-chattering, finely dressed Chinese ladies and gentlemen, serves only noodles. They bring you a bowl of noodles and you choose one of about 400 things to put on top of it. It is sensational. It is friendly and it is professional and it won’t f*** up your credit card! Also, if like me you love a roasted, free-range, Gressingham duck with giblet gravy and apple sauce, or, if like me you are nostalgic enough and romantic enough to think that the Tour d’Argent in Paris serves the best duck, then you must visit the Imperial Duck Trading Corporation – actually, that is not its name, it is, in fact, called Quanjaid. It’s on the second or third floor of one of these imposing skyscrapers, it has been in operation since about 1850 and it specialises, of course, in Peking Duck. These specially reared and fattened ducks are air-dried for two days before they are roasted vertically in front of a wood-fired oven so that the skin is crisp and almost opaque, like golden glass. The duck is served to you with its head on, the skin is deftly carved off and given to you separately, and then comes the unctuous meat, the little pancakes, the plum sauce, the strips of spring onions and cucumber, which you roll and munch, meanwhile sipping a creamy duck broth, and finally the waiter comes back and carves the long duck tongue into fine slivers for you. But he too looked like someone from Mars because he was wearing a white suit, white boots, white gloves and a mask. As you leave you notice all the signed photographs on the wall from Nixon to Chairman Mao and beyond.

Thank you, China. I will be back.

Keith Floyd

Uzes

South East France

June 2005

Kissing don’t last, cooking do

Confucious said, ‘Give a man a fish and he will live for a day. Teach a man to fish and he will live forever.’ He also said, although he, of course, said a lot of things, ‘Eating is the utmost important part of life.’ I don’t have to hand any of his quotations on the art of lovemaking.

The celebrated food writer and gastronaught, although I fear she would disapprove of that term, Jane Grigson, who, along with Elizabeth David, was one of the best food writers in the English language, said that cooking is a very simple art, you apply heat to raw food and keep it as simple as possible.

In Britain we are blessed with a multicultural, culinary society and can enjoy the world’s food cooked by Thais, Italians, French, Spanish, Indians and, of course, the likes of home-grown British talent such as Gary Rhodes, Gordon Ramsay, Antony Worrall Thompson, et al. There is not a town in the land that does not have a Chinese takeaway. It is popular food and invariably it is often not very good. It is so Westernized – that is to say it does not have the ‘umph’ of real Eastern cooking and it has actually become a bit of a joke. Stir-fried bean sprouts with a bit of chicken and no real seasoning, no real spice, no real passion behind it is quite frankly a disaster. However, there are good restaurants around in places like Manchester, Soho and, indeed, in Brighton, where the excellent China Garden serves unctuous, sticky rice in lotus leaves and curried whelks, which are as good as anything you can find anywhere in the world, although I do acknowledge that Hong Kong and Taiwan are pretty good too! In Hong Kong there is a restaurant that serves dim sum – it seats 1,000 people and the waiters and waitresses endlessly push trollies to your table with delectable compositions, be it prawns, pork, chicken, frog’s legs, sea snakes, sea cucumbers, or whatever. Brilliant dumplings, excellent concoctions of noodles.

So what then is Chinese food? It is not a little box of quickly fried red and green peppers, a bit of beef and black bean sauce purchased after 10 pints of lager at 11.00 at night. Chinese food is the result of thousands of years of civilization. The vast country of China has suffered from poor harvests and during those lean years, to stay alive, the Chinese would explore anything edible. As a consequence, many wonderful and slightly incredible ingredients, such as lily buds, wood ears, vegetable peels and shark’s fins, were incorporated into the exquisite richness and variety of Chinese food. You may not want to eat sea cucumbers (a kind of a slug), you may not want a piece of grilled snakeskin or a brochette of strange insects. I think I don’t either, but the sheer volume and variety of food is gastronomically mind boggling – particularly, for me, the noodles. There are so many – egg noodles, wheat noodles, rice flour noodles. Wheat noodles are common in Shanghai. These are thick and when cooked and stir-fried with a savoury sauce of chicken, pork or shrimp are delicious. Rice flour noodles, often known as Singapore style, use thin, vermicelli noodles seasoned with curry powder and mixed with shrimp or barbequed pork or ham.