Полная версия:

Corrag

Corrag

Susan Fletcher

FOURTH ESTATE • London

For those who were there

I had an unexpected request the other day; there had been two bad landslides where the bulldozers have been working on the slate banks. Someone…said it was because the workmen had been disturbing the grave of Corrag. Corrag was a famous Glencoe witch…One point of interest about her is that, in spite of reputed badness, she was to have been buried on the Burial Island of Eilean Munda. It was often noticed that however stormy the sea, or wild the weather, it habitually calmed down to allow the boat out for a burial. In the case of Corrag the storm did not cease till finally she was buried beside where the road now runs. By the way, in the Highlands, islands were used for burial very widely. Remember wolves remained here very much later than in the south.

Barbara Fairweather

Clan Donald Magazine No. 8

1979

More things are learnt in the woods than in books. Animals, trees and rocks teach you things not to be heard elsewhere.

St Bernard (1090–1153)

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

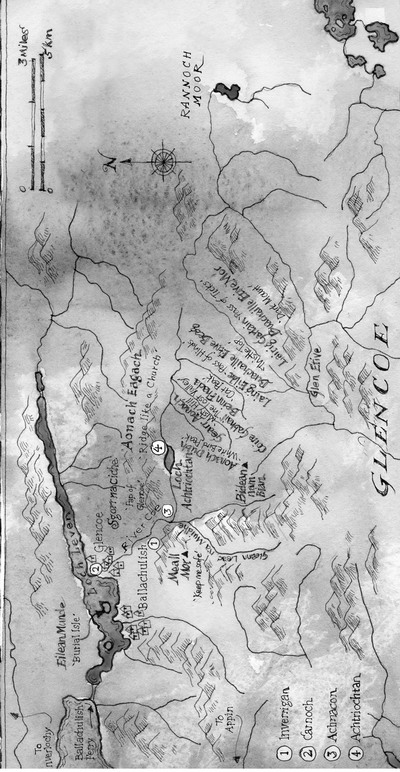

Map

Letter

One

I

II

III

Two

I

II

III

IV

Three

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

Four

I

II

Five

Letter

I

Afterword

Acknowledgements

Author’s Note

Also by Susan Fletcher

Copyright

About the Publisher

Map

Letter

Edinburgh

18th February 1692

Jane

I can’t think of a winter that has been this cruel, or has asked so much of me. For weeks now, it has been blizzards, and ice. The wind is a hard, northern one – it finds its way inside my room and troubles this candle that I’m writing by. Twice it has gone out. For the candle’s sake I must keep this brief.

I have news as foul as the weather.

Edinburgh shivers, and coughs – but it whispers, too. In its wynds and markets, there are whispers of treachery – of a mauling in the brutish, Highland parts. Deaths are often violent there, but I hear these were despicably done. A clan, they say, has been slaughtered. Their guests rose up against them and killed them in their beds.

On its own, this is abhorrent. But there is more.

Jane – they say it was soldier’s work.

Of all people, you know my mind. You know my heart, and if this is true – if it was soldiers’ hands that did this bloodiness – then surely it was the King who ordered it (or I will say the Orange, pretending one, for he is not my king).

I must leave for this valley. They call it wild and remote, and it’s surely snowbound at this time – but it’s my duty. I must learn what I can and report it, my love, for if William is behind this wickedness it may prove his undoing, and our making. All I wish, as you know, is to restore the true King to his throne.

Pray for my task. Ask the Lord for its safe and proper outcome. Pray for the lives of all our brothers in this cause, for we risk so much in its name. Pray, too, for better weather? This snow gives me a cough.

The candle gutters. I must end this letter, or I shall soon be writing by the fire’s light, which is not enough light for my eyes.

In God’s love, and my own,

Charles

I

‘The Moon is Lady of this.’

of Privet

Complete Herbal

Culpeper 1653

When they come for me, I will think of the end of the northern ridge, for that’s where I was happiest – with the skies and wind, and the mountains being dark with moss, or dark with the shadow of a cloud moving across them. I will think of how it is when part of a mountain brightens very suddenly, so it is like that rock is chosen by the sun – marked out by sunshine from all the other rocks. It will shine, and then grow dark again. And I’ll stand with my skirts blowing, make my way home. I will have that sunlit rock in me. I will keep it safe.

Or I’ll think of how I ran with the snow coming down. There was no moon, but I saw the morning star, which they say is the devil’s star but it is love’s star, too. It shone, that night – so brightly. And I ran beneath it, thinking let all be well let all be well. Then I saw the land below which was so peaceful, so white and still and sleeping that I thought maybe the star had heard and all was well – no death was coming near. It was a night of beauty, then. For a while, it was the greatest beauty I had ever seen in all my life. My little life.

Or I will think of you.

In my last, quiet moments, I will think of him beside me. How, very softly, he said you…

Some called it a dark place – like there was no goodness to be found inside those hills. But I know there was goodness. I climbed into its snowy heights. I crouched by the loch and drank from it, so my hair was in the water, and I lifted up my head to see the mist come down. On a clear, frosty night, when they said all the wolves were gone, I heard a wolf call from Bidean nam Bian. It was such a long, mournful call that I closed my eyes to hear it. It mourned its own end, I think, or ours – as if it knew. Those nights were like no other nights. The hills were very black, like they were shapes cut out of cloth, and the cloth was dark-blue, starry sky. I knew stars – but not as those stars were.

Those were its nights. And its days were clouds and rocks. Its days were paths in grass, and pulling herbs from soggy places that stained my hands and left their peaty smell on me. I was damp, peat-smelling. Deer trod their ways. I also trod them, or nestled in their hollows and felt their old deer-warmth. I saw what their black deer-eyes had seen, before my own. Those were its days – small things. Like how a river parts around a rock and joins again.

It was not dark. No.

I had to find it – darkness. I had to push rocks from their resting place, or look for it in caves. The summer nights could be so light, so full of light that I curled up like a mouse, hid my eyes beneath my hand so I might find a little dark to sleep inside. It is how I sleep, even now – tucked up.

I will think this way. When my life is ending. I will not think of musket shots or how it smelt by Achnacon. Not of bloodied things.

I will think of the end of the northern ridge. How my hair blew all about me. How I saw the glen go light and dark with clouds, or how he said you’ve changed me, as he stood by my side. I thought this is the place, as I stood there. I thought this is my place – mine, where I was meant for.

It was waiting for me, and I found it, in the end.

I was always for places. I was made for the places where people did not go – like forests, or the soft marshy ground where feet sank down and to walk there made a suck suck sound. Me as a child was often in bogs. I watched frogs, or listened to how rushes were in breezes and I liked that – how they sounded. Which is how I knew what I was.

See? Cora said, smiling.

She was for places too. She trawled her skirts over mud, and wet sand. She was brambled, and fruit-stained, and once she lived in an old waterwheel, upon its soft, green wood. She said she was lonesome there – but what choice did I have? Tell me? Not much. Some people cannot have a peopled life. We try for it. We go to markets, and say hello. We help to bring the hay in, and pick the cider apples from their bee-noisy trees, but it takes very little – a hare, or a strange moon – for hag to come. Whore. They raise an eyebrow, then. They call for ropes to bind us, so that we grow so sad and afraid for our small lives that we turn to empty places – and that makes them say hag even more. She lives on her own. Walks in shadows, I hear…But where else is safe? No towns are. All that was left for Cora was high-up parts, or sunken ones. Places of such wind that trees were bent over, and had no leaves. Normal folk did not go there, so we did – her, and I.

I’ve lived in caves, and woods. My feet have been torn up on thorns. When I crept into towns for eggs or milk they crossed themselves, spat. I know spitting. I know its sound, too, like retching, like a cat pulling up the bones of a bird it ate up whole, all sharp parts in with feathers. They hissed, we know what you are…And did they? They thought they did. In my English life, they took old truths – my snowy birth, how I liked marshy places – and pressed them into proper lies, like how they saw me lift a shoulder up and turn into a crow. I never did that.

I have lived on open land. On moors, in windy weather.

I’ve lived in a hut I made myself, with my own hands – of moss, and branches, and stone. The mountains looked down on me, as I curled up at night.

And now? Now I live here.

In a cell, with chains.

It snows. From the little window, I can see it snows. It’s been months, I think, of snowing – of bluish ice, and cold. Months of clouded breath. I blow, and see my breath roll out and I think

look. That is my life. I am still living.

I like it – snow. I always did. I was born in a sharp, hard-earth December, as the church folk sang about three wise men and a star through their chattering teeth. Cora said that the weather you are born in is yours, all your life – your own weather. You will shine brightest in snowstorms she told me. Oh yes…I believed her – for she was born in thunder, and was always stormy-eyed.

So snow and cold is mine. And I have known some winters. I’ve heard fish knock beneath their ice. I’ve seen a trapdoor freeze so it could not go bang, though they still took the man’s life away, in the end. Once, in these high Scottish passes, I made a hole in the drifts with my own hands, and crept inside, so soldiers ran past not knowing I crouched in it. This saved my life, I think. I’m a hardy thing. People die from the cold, but I haven’t. I’ve not had blue skin, not once – a man said it was the evil fire in me that kept me warm, and bind that harlot up. But it was no evil fire. I was just born in snowy weather and had to be hardy to stay living. I wanted to live, in this life. So I grew strong, and did.

Winter is an empty season, too. Safer. For who wanders out on frosty nights, or drifty white mornings? Not many, and none by choice. In my travelling days, with my grey mare and north-and-west in my head, I might see no one for days. Just us, galloping. Me and the mare, with snowflakes in our manes. And when we did see people, it was mostly desperate ones – gypsies, clawing for nuts, or broken men. Drunks. A thief or two. And foxes, running from the hunter’s gun with that look in their eyes – that wild, dread look, which I know. Once I found some people kneeling in a gloomy Scottish wood – they took Christ’s body into their mouths, and a priest was there, saying church things. I watched, and thought, why here? And at night? I did not understand. I have never understood much on God, or politics. But I know these kneeling folk were Covenanters, which is a gunpowder word. They could be killed, for praying – which is why they did it in woods, at night.

And I passed a lone girl, once. She was my age, or less. We met in some Lowland trees, in the early hours, and we slowed, brushed hands. We looked on each other for a moment or two, with be careful in our eyes – be safe, and wise. For who else is as hated as we are? Who is more lonesome, than ones called witch? Briefly, we both had a friend. But we were hunted creatures – her, the fox and I. So I took the path she had come by, and she took my old path.

Witch. Like a shadow, it is never far.

There are other names, too – hag, and whore. Wicked piece. Harlot is common, also, and such names are too cruel to tie upon a dog – but they’ve been tied, easily, on me. I drag them. Vile matter once, like I was a fluid hawked up in the street – like I was not even human. I cried after that. In the market, once, Cora was Devil’s hole.

But witch…

The oldest name. The worst. I know its thick, mud-weight. I know the mouth’s shape when it says it. I reckon it’s the most hated word of all – more hated than Highland, or Papist is. Some won’t say William like it’s poison – I know many people don’t want him to be King. But he is King, for now. And I was always witch.

That December birth of mine was a troubled one. My mother bled too much, and cursed, and she roared so long that her throat split in two, like it can in painful times. Her roar had two voices – one hers, and one the Devil’s, or so said the folk who heard it from the church. I fell out to this sound. I slipped out upon the glinting, blue-eyed earth, beneath a starry sky, and she laughed. She wept, and laughed at me. Said my life would be like this – cold, hard, outdoors.

Witch she said, weeping.

She was the first to say it.

Later, at daybreak, she gave me my proper name.

I say it – look. Witch…And my breath clouds so the word is white, rolls out.

I have tried to not mind it. I’ve tried so hard.

I have tried to say it does not hurt, and smile. And I can reason that witch has been a gift, in its way – for look at my life…Look at the beauty that witch has brought me to. Such pink-sky dawns, and waterfalls, and long, grey beaches with a thundering sea, and look what people I met – what people! I’ve met some sovereign lives. I’ve met wise, giving, spirited lives which I would not have done, without witch. What love it showed me, too. No witch, and I would not have met the man who made me think him, him, him – all the time. Him, who tucked a strand of my hair behind my ear. Him who said you…

Alasdair.

Witch did that. So maybe it’s been worth it all, in the end.

I wait for my death. I think him, and wonder how many days I have left to think it in. I turn my hands over, and stare. I feel my bones under my skin – my shins, my little hips – and wonder what will happen to them when I’m gone.

I wonder plenty.

Like who will remember me? Who knows my true name – my full one? For witch is what they will shout, as I’m dying. Witch as the dark sky is filled with fiery light.

It is like I have lived many lives. This is what I tell myself – many lives. Four of them. Some folk have one life and know no other, which is fine, and maybe it’s the best way of it – but it’s not what I was meant for. I was a leaf blown all over.

Four lives, like there are seasons.

Which was the best of them? I would live them all again, for all had their goodnesses. I would like to be back in the cottage by the burn, with cats asleep in the eaves. Or to walk in the thick elm wood – which was dappled, full of grubs. Cora called it a healer’s friend, for she found most of her cures in there. It was where I undid my shoulder for the first time, and where the best pheasants were for catching and eating, which sometimes we did.

Or I would like to be back in my second life. My second life was like flying. It was empty lands, and wind, and mud on my face from her hooves. I loved that grey mare. My fingers were knotted into her mane as she galloped over miles and miles, snorting and throwing up earth. I held on, thinking go! Go!

But it’s my third life I would like again, most of all. My glen one. I lived it too briefly – it was too short a life. Yet it’s the best I’ve known – for where else did I see my reflection and think you are where you should be – at last. And where else were there people who did not mind me, and let me be? They pressed a cup into my hand, said drink. They left hens by my hut, as thank you, and raised a hand in greeting, and I had craved that all my lonesome life. All I’d deeply wanted was love, and human friends. To stand in a crowd and think these are my kind. My people. That was my third life.

And my fourth one is this one – in here.

Yes I’m for places, mostly. But it is because they made me so – the ones who eyed me, and did not trust herbs or a grey-eyed girl. They made me for places, by hissing witch. They sent me up, up, into the airy parts.

But the truth is that I wish I could have been with people more – with those Highlanders who never minded filthy hands, or tangles, or my English voice, and who slowed to look at geese flying south, like I did.

So I am for places – wind, and trees.

But I am for good, kind people most of all.

Like Alasdair. Cora. The Chief of that clan, who is dead now.

I think, too, of Gormshuil. I think of how she was, the night before the murders – how she put her hand near my cheek, but not on it, as if she was afraid of touching me. She said there is blood coming – but she said more than that. A man will find you. A man will come to you, and see your iron wrists, your small feet. He will write of things – such things…

What were those words? I brushed them away. I thought it was henbane talking, or some half-had dream. I saw Gormshuil in the falling snow, and shook my head. No…My wrists? I looked down upon them and thought they are pink, and flesh. They are fine. It was the herb – surely. Her teeth were green with it.

But blood was spilled, in Glencoe, like she said. Blood did come.

A man will find you.

I hear these words, now.

Who says them? I say them. I say Gormshuil’s words, and I remember how she looked at me. I see the deep lines on her face which loss had made, and the scalp beneath her snow-wet hair. I wonder if she is also dead. Perhaps she is. But I think she still lives on that blustery peak.

A man will find you. Iron wrists.

Some things we know. We hear them, and think I know – like we’ve always had the knowledge waiting in ourselves. And I know. She was right. There was a light in her when she said iron wrists – a wide, astonished light, as if she’d never been so sure. Like how a deer is, when it lifts its head and sees you, and is scared – for it knows you are real, and breathing, and that you’ve crouched there all this while.

So I wait. With my shackles, and dirt.

I wait, and he comes. A man I’ve never met is riding to my cell.

When I tuck up in the straw, I stare into the dark and see my other lives. I see the bogs, the glen. But I also see his face.

His spectacles.

His neat, buckled shoes, and leather case.

The Eagle Inn

Stirling

Jane

I write this letter from Stirling. It is poor ink so forgive the poorer hand. Forgive, too, my bad humour. My supper was barely a crumb and my bed is damp from the cold, or the previous sleeper. What’s more, I was hoping to be further north by now, but the weather remains unkind. We’ve kept to the lower roads. We lost a horse two days ago, which has stolen hours, or days, from us. It’s a wildly unsatisfactory business.

Let me go back a while – you shall know each part, as a wife should.

I left Edinburgh on Friday, which seems many months gone. I am indebted to a gentleman who lent me a sturdy cob and some funds – though I cannot give his name. I hate to withhold truths from you, but it may endanger him to write much more; I will simply say he is powerful, respected and sympathetic to our cause. Indeed, I glimpsed an embroidered white rose on his coat, which we all know says Jacobite. We drank to King James’ health and his speedy return – for he will return. We are few in number, Jane, but we are strong.

My thoughts were to make for a place named Inverlochy, on the Scottish north-west coast. It has a fort, and a settlement. Also it is a mere day’s journey from this ruined Glen of Coe. The gentleman assured me that its governor, a Colonel Hill, is kindly, and wise, and I might find lodgings with him – but I fear the snow prevents this. I travel with two servants who speak of thick blizzards on the moor that lies between the fort and here. They’re surly men, and locals. As I write they are in the town’s dens, drinking. I don’t trust them. I’m minded to insist we take this snowy route, no matter – for we have ridden this far through such weather. But I cannot risk another horse. Nor can I serve God if I perish on Rannoch Moor.

So tomorrow, our journey takes us west. Inverlochy must wait.

We are headed, now, for the town of Inverary – a small, Campbell town on the shores of Loch Fyne. The coast has a milder climate, I hear. I also hear the Campbells are a strong and wealthy people – I hope for a warmer bed than this one that Stirling provides. There, we might fatten our horses and ourselves, and rest, and wait for the thaw. It sounds a decent resting place. But I must be wary, Jane – these Campbells are William’s men. They are loyal to him, and support him – they would not take kindly to my cause. They’d call it treachery, or worse. So I must hide my heart, and hold my tongue.

Wretched weather. My cough is thicker and I worry my chilblains might come back. Do you remember how I suffered from them in our first married winter? I would not wish for them again.

I feel far from you. I feel far from Ireland. Also, from like-minded men – I write to them in London, asking for their help, in words or in funds to assist me, but I hear nothing from them. Perhaps this weather slows those letters. Perhaps it slows these letters to you.

Forgive me. I am maudlin tonight. It is hunger that troubles me – for food, for warmth, for a little hope in these hopeless times. For you, too, my love. I think of you reading this by the fire, in Glaslough, and I wish I could be with you. But I must serve God.

Dear Jane. Keep warm and dry.

I will endeavour to do the same, and shall write to you from Inverary. It may be an arduous journey, so do not expect a letter in haste. But have patience, as you have other virtues – for a letter will come.

In God’s love, as always,

Charles