Полная версия:

The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East

THE GREAT WAR FOR CIVILISATION

The Conquest of the Middle East

ROBERT FISK

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This revised eBook edition published by Fourth Estate in 2014

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate in 2005

Previously published in paperback by Harper Perennial in 2006

Copyright © Robert Fisk 2005, 2006

Quotation of Carl Sandburg’s ‘Grass’ taken from Chicago Poems, copyright 1916 by Holt, Rinehart and Winston and renewed 1944 by Carl Sandburg, reproduced by permission of Harcourt Inc.

Quotation from W. B. Yeats’s ‘Lapiz Lazuli’ reproduced by permission of A. P. Watt Ltd. on behalf of Michael B. Yeats.

Quotation from Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace (edited and translated 1954 by Louis and Aylmer Maude) reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press.

Quotation from G. B. Shaw’s Major Barbara reproduced by permission of The Society of Authors, on behalf of the Bernard Shaw Estate.

Quotation from T. S. Eliot’s preface to The Dark Side of the Moon reproduced by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd.

Robert Fisk asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

The publishers have tried to trace and acknowledge copyright-holders,

but would be eager to rectify any omissions.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9781841150086

Ebook Edition © JUNE 2014 ISBN: 9780007370405 Version: 2017-01-12

PRAISE

‘There is nobody in British journalism to match Robert Fisk. This book is his testament … His technique is well-honed: a vivid eyewitness account, unmatchable quotes and the killer detail that everyone else has missed’

Sunday Times

‘Brilliant … powerfully written. He has turned a slightly dubious and over-romanticised craft into an honourable vocation’

PHILLIP KNIGHTLEY, Independent on Sunday

‘This book will make Robert Fisk an even greater star—deeply moving’

Literary Review

‘A remarkable book’

New Statesman

‘Fisk is one of the best-known reporters in the world … He interleaves political analysis, recent history and his own adventures with the real stories which concern him [and] writes with a marvellous resource of image and language. His investigative reporting is lethally painstaking’

NEAL ACHERSON, Independent

‘Part-memoir, all heart, this 1,328-page behemoth will delight Fisk’s fans, infuriate his foes and fascinate all’

DONALD MORRISON, Financial Times

‘A fierce indictment of Britain and the United States’

Sunday Telegraph

‘A mammoth and magisterial work, the definitive summation of what has gone wrong in the West’s foreign policies towards Arabia. It should be compulsory reading for those who aspire to lead’

Scottish Sunday Herald

‘It is a history book which journalists, politicians and academics will turn to again and again in the years ahead to grasp the details of the Middle East’

WILLIAM GRAHAM, Irish News

‘Fisk is a gifted writer and an accomplished storyteller … [readers] will enjoy the colorful narrative [and] the wealth of hard-won narrative detail accumulated over his decades of intrepid reporting’

Economist

‘Vivid, graphic, intense and very personal … this is a book of unquestionable importance’

Washington Post

DEDICATION

For Bill and Peggy, who taught me to love books and history

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

PRAISE

DEDICATION

LIST OF MAPS

PREFACE

1 ‘One of Our Brothers Had a Dream …’

2 ‘They Shoot Russians’

3 The Choirs of Kandahar

4 The Carpet-Weavers

5 The Path to War

6 ‘The Whirlwind War’

7 ‘War against War’ and the Fast Train to Paradise

8 Drinking the Poisoned Chalice

9 ‘Sentenced to Suffer Death’

10 The First Holocaust

11 Fifty Thousand Miles from Palestine

12 The Last Colonial War

13 The Girl and the Child and Love

14 ‘Anything to Wipe Out a Devil …’

15 Planet Damnation

16 Betrayal

17 The Land of Graves

18 The Plague

19 Now Thrive the Armourers …

20 Even to Kings, He Comes …

21 Why?

22 The Die Is Cast

23 Atomic Dog, Annihilator, Arsonist, Anthrax and Agamemnon

24 Into the Wilderness

KEEP READING

NOTES

FOOTNOTES

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

CHRONOLOGY

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ALSO BY THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

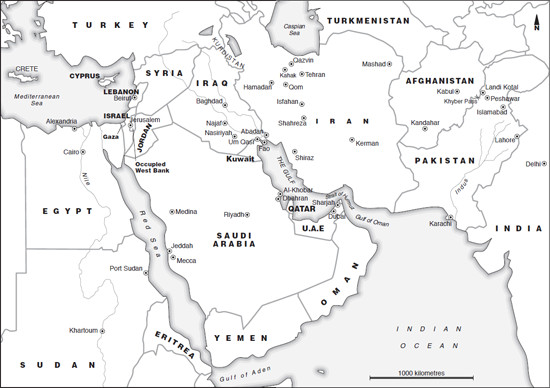

LIST OF MAPS

The Middle East Afghanistan Iran Iraq The Sykes-Picot Agreement The Iran—Iraq war The Armenian Genocide Israel/Palestine Algeria Saudi Arabia/Kuwait/IraqAll maps drawn by HLStudios, Long Hanborough, Oxford, except the Armenian Genocide, produced by the Armenian National Institute (ANI) (Washington DC) and the Nubarian Library (Paris). © ANI, English Edition Copyright 1998.

PREFACE

When I was a small boy, my father would take me each year around the battlefields of the First World War, the conflict that H. G. Wells called ‘the war to end all wars’. We would set off each summer in our Austin of England and bump along the potholed roads of the Somme, Ypres and Verdun. By the time I was fourteen, I could recite the names of all the offensives: Bapaume, Hill 60, High Wood, Passchendaele … I had seen all the graveyards and I had walked through all the overgrown trenches and touched the rusted helmets of British soldiers and the corroded German mortars in decaying museums. My father was a soldier of the Great War, fighting in the trenches of France because of a shot fired in a city he’d never heard of called Sarajevo. And when he died thirteen years ago at the age of ninety-three, I inherited his campaign medals. One of them depicts a winged victory and on the obverse side are engraved the words: ‘The Great War for Civilisation’.

To my father’s deep concern and my mother’s stoic acceptance, I have spent much of my life in wars. They, too, were fought ‘for civilisation’. In Afghanistan, I watched the Russians fighting for their ‘international duty’ in a conflict against ‘international terror’; their Afghan opponents, of course, were fighting against ‘communist aggression’ and for Allah. I reported from the front lines as the Iranians struggled through what they called the ‘Imposed War’ against Saddam Hussein – who dubbed his 1980 invasion of Iran the ‘Whirlwind War’. I’ve seen the Israelis twice invading Lebanon and then reinvading the Palestinian West Bank in order, so they claimed, to ‘purge the land of terrorism’. I was present as the Algerian military went to war with Islamists for the same ostensible reason, torturing and executing their prisoners with as much abandon as their enemies. Then in 1990 Saddam invaded Kuwait and the Americans sent their armies to the Gulf to liberate the emirate and impose a ‘New World Order’. After the 1991 war, I always wrote down the words ‘new world order’ in my notebook followed by a question mark. In Bosnia, I found Serbs fighting for what they called ‘Serb civilisation’ while their Muslim enemies fought and died for a fading multicultural dream and to save their own lives.

On a mountaintop in Afghanistan, I sat opposite Osama bin Laden in his tent as he uttered his first direct threat against the United States, pausing as I scribbled his words into my notebook by paraffin lamp. ‘God’ and ‘evil’ were what he talked to me about. I was flying over the Atlantic on 11 September 2001 – my plane turned round off Ireland following the attacks on the United States – and so less than three months later I was in Afghanistan, fleeing with the Taliban down a highway west of Kandahar as America bombed the ruins of a country already destroyed by war. I was in the United Nations General Assembly exactly a year after the attacks on America when George Bush talked about Saddam’s non-existent weapons of mass destruction, and prepared to invade Iraq. The first missiles of that invasion swept over my head in Baghdad.

The direct physical results of all these conflicts will remain – and should remain – in my memory until I die. I don’t need to read through my mountain of reporters’ notebooks to remember the Iranian soldiers on the troop train north to Tehran, holding towels and coughing up Saddam’s gas in gobs of blood and mucus as they read the Koran. I need none of my newspaper clippings to recall the father – after an American cluster-bomb attack on Iraq in 2003 – who held out to me what looked like half a crushed loaf of bread but which turned out to be half a crushed baby. Or the mass grave outside Nasiriyah in which I came across the remains of a leg with a steel tube inside and a plastic medical disc still attached to a stump of bone; Saddam’s murderers had taken their victim straight from the hospital where he had his hip replacement to his place of execution in the desert.

I don’t have nightmares about these things. But I remember. The head blasted off the body of a Kosovo Albanian refugee in an American air raid four years earlier, bearded and upright in a bright green field as if a medieval axeman has just cut him down. The corpse of a Kosovo farmer murdered by Serbs, his grave opened by the UN so that he re-emerges from the darkness, bloating in front of us, his belt tightening viciously round his stomach, twice the size of a normal man. The Iraqi soldier at Fao during the Iran – Iraq war who lay curled up like a child in the gun-pit beside me, black with death, a single gold wedding ring glittering on the third finger of his left hand, bright with sunlight and love for a woman who did not know she was a widow. Soldier and civilian, they died in their tens of thousands because death had been concocted for them, morality hitched like a halter round the warhorse so that we could talk about ‘target-rich environments’ and ‘collateral damage’ – that most infantile of attempts to shake off the crime of killing – and report the victory parades, the tearing down of statues and the importance of peace.

Governments like it that way. They want their people to see war as a drama of opposites, good and evil, ‘them’ and ‘us’, victory or defeat. But war is primarily not about victory or defeat but about death and the infliction of death. It represents the total failure of the human spirit. I know an editor who has wearied of hearing me say this, but how many editors have first-hand experience of war?

Ironically, it was a movie that propelled me into journalism. I was twelve years old when I saw Alfred Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent, a black and white 1940 creaky of patriotism and equally black humour in which Joel McCrea played an American reporter called John Jones – renamed Huntley Haverstock by his New York editor – who is sent in 1939 to cover the approaching war in Europe. He witnesses an assassination, chases Nazi spies in Holland, uncovers Germany’s top agent in London, is shot down in an airliner by a German pocket battleship and survives to scoop the world. He also wins the most gorgeous woman in the movie, clearly an added bonus for such an exciting profession. The film ends in the London Blitz with a radio announcer introducing Haverstock on the air. ‘We have as a guest tonight one of the soldiers of the press,’ he shouts amid the wail of air raid sirens, ‘… one of the little army of historians who are writing history from beside the cannon’s mouth …’

I never looked back. I read my father’s conservative Daily Telegraph from cover to cover, always the foreign reports, lying on the floor beside the fire as my mother pleaded with me to drink my cocoa and go to bed. At school I studied The Times each afternoon. I ploughed through Khrushchev’s entire speech denouncing Stalin’s reign of terror. I won the school Current Affairs prize and never – ever – could anyone shake me from my determination to be a foreign correspondent. When my father suggested I should study law or medicine, I walked from the room. When he asked a family friend what I should do, the friend asked me to imagine I was in a courtroom. Would I want to be the lawyer or the reporter on the press bench, he asked me. I said I would be the reporter and he told my father: ‘Robert is going to be a journalist.’ I wanted to be one of the ‘soldiers of the press’.

I joined the Newcastle Evening Chronicle, then the Sunday Express diary column, where I chased vicars who had run off with starlets. After three years, I begged The Times to hire me and they sent me to Northern Ireland to cover the vicious little conflict that had broken out in that legacy of British colonial rule. Five years later, I became one of those ‘soldiers’ of journalism, a foreign correspondent. I was on a beach at Porto Covo in Portugal in April of 1976 – on holiday from Lisbon where I was covering the aftermath of the Portuguese revolution – when the local postmistress shouted down the cliff that I had a letter to collect. It was from the paper’s foreign editor, Louis Heren. ‘I have some good news for you,’ he wrote. ‘Paul Martin has requested to be moved from the Middle East. His wife has had more than enough, and I don’t blame her. I am offering him the number two job in Paris, Richard Wigg Lisbon – and to you I offer the Middle East. Let me know if you want it … It would be a splendid opportunity for you, with good stories, lots of travel and sunshine …’ In Hitchcock’s thriller, Haverstock’s editor calls him to his office before sending him to the European war and asks him: ‘How would you like to cover the biggest story in the world today?’ Heren’s letter was less dramatic but it meant the same thing.

I was twenty-nine and I was being offered the Middle East – I wondered how King Feisal felt when he was ‘offered’ Iraq or how his brother Abdullah reacted to Winston Churchill’s ‘offer’ of Transjordan. Louis Heren was in the Churchillian mode himself, stubborn, eloquent, and an enjoyer of fine wines as well as himself a former Middle East correspondent. If the stories were ‘good’ in journalistic terms, however, they would also prove to be horrific, the travel dizzying, the ‘sunshine’ as cruel as a sword. And we journalists did not have the protection – or the claims to perfection – of kings. But now I could be one of ‘the little army of historians who are writing history from beside the cannon’s mouth’. How innocent, how naive I was. Yet innocence, if we can keep it, protects a journalist’s integrity. You have to fight to believe in it.

Unlike my father, I went to war as a witness rather than a combatant, an ever more infuriated bystander to be true, but at least I was not one of the impassioned, angry, sometimes demented men who made war. I worshipped the older reporters who had covered the Second World War and its aftermath: Howard K. Smith, who fled Nazi Germany on the last train from Berlin before Hitler declared war on the United States in 1941; James Cameron, whose iconic 1946 report from the Bikini atom tests was perhaps the most literary and philosophical article ever published in a newspaper.

Being a Middle East correspondent is a slightly obscene profession to follow in such circumstances. If the soldiers I watched decided to leave the battlefield, they would – many of them – be shot for desertion, at least court-martialled. The civilians among whom I was to live and work were forced to stay on under bombardments, their families decimated by shellfire and air raids. As citizens of pariah countries, there would be no visas for them. But if I wanted to quit, if I grew sick of the horrors I saw, I could pack my bag and fly home Business Class, a glass of champagne in my hand, always supposing – unlike too many of my colleagues – that I hadn’t been killed. Which is why I cringe each time someone wants to psycho-babble about the ‘trauma’ of covering wars, the need to obtain ‘counselling’ for us well-paid scribes that we may be able to ‘come to terms’ with what we have seen. No counselling for the poor and huddled masses that were left to Iraq’s gas, Iran’s rockets, the cruelty of Serbia’s militias, the brutal Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, the computerised death suffered by Iraqis during America’s 2003 invasion of their country.

I don’t like the definition ‘war correspondent’. It is history, not journalism, that has condemned the Middle East to war. I think ‘war correspondent’ smells a bit, reeks of false romanticism; it has too much of the whiff of Victorian reporters who would view battles from hilltops in the company of ladies, immune to suffering, only occasionally glancing towards the distant pop-pop of cannon fire. Yet war is, paradoxically, a very powerful, unique experience for a journalist, an opportunity to indulge in the only vicarious excitement still free of charge. If you’ve seen the movies, why not experience the real thing? I fear that some of my colleagues have died this way, heading to war on the assumption that it’s still Hollywood, that the heroes don’t die, that you can’t get killed like the others, that they’ll all be Huntley Haverstocks with a scoop and the best girl. But you can get killed. In just one year in Bosnia, thirty of my colleagues died. There is a little Somme waiting for all innocent journalists.

When I first set out to write this book, I intended it to be a reporter’s chronicle of the Middle East over almost three decades. That is how I wrote my previous book, Pity the Nation, a first-person account of Lebanon’s civil war and two Israeli invasions.* But as I prowled through the shelves of papers in my library, more than 350,000 documents and notebooks and files, some written under fire in my own hand, some punched onto telegram paper by tired Arab telecommunications operators, many pounded out on the clacking telex machines we used before the Internet was invented, I realised that this was going to be more than a chronology of eyewitness reports.

My father, the old soldier of 1918, read my account of the Lebanon war but would not live to see this book. Yet he would always look into the past to understand the present. If only the world had not gone to war in 1914; if only we had not been so selfish in concluding the peace. We victors promised independence to the Arabs and support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Promises are meant to be kept. And so those promises – the Jews naturally thought that their homeland would be in all of Palestine – were betrayed, and the millions of Arabs and Jews of the Middle East are now condemned to live with the results.

In the Middle East, it sometimes feels as if no event in history has a finite end, a crossing point, a moment when we can say: ‘Stop – enough – this is where we will break free.’ I think I understand that time-warp. My father was born in the century before last. I was born in the first half of the last century. Here I am, I tell myself in 1980, watching the Soviet army invade Afghanistan, in 1982 cowering in the Iranian front line opposite Saddam’s legions, in 2003 observing the first American soldiers of the 3rd Infantry Division cross the great bridge over the Tigris river. And yet the Battle of the Somme opened just thirty years before I was born. Bill Fisk was in the trenches of France three years after the Armenian genocide but only twenty-eight years before my birth. I would be born within six years of the Battle of Britain, just over a year after Hitler’s suicide. I saw the planes returning to Britain from Korea and remember my mother telling me in 1956 that I was lucky, that had I been older I would have been a British conscript invading Suez.

If I feel this personally, it is because I have witnessed events that, over the years, can only be defined as an arrogance of power. The Iranians used to call the United States the ‘centre of world arrogance’, and I would laugh at this, but I have begun to understand what it means. After the Allied victory of 1918, at the end of my father’s war, the victors divided up the lands of their former enemies. In the space of just 17 months, they created the borders of Northern Ireland, Yugoslavia and most of the Middle East. And I have spent my entire career – in Belfast and Sarajevo, in Beirut and Baghdad – watching the peoples within those borders burn. America invaded Iraq not for Saddam Hussein’s mythical ‘weapons of mass destruction’ – which had long ago been destroyed – but to change the map of the Middle East, much as my father’s generation had done more than eighty years earlier. Even as it took place, Bill Fisk’s war was helping to produce the century’s first genocide – that of a million and a half Armenians – laying the foundations for a second, that of the Jews of Europe.

This book is also about torture and executions. Perhaps our work as journalists does open the door of the occasional cell. Perhaps we do sometimes save a soul from the hangman’s noose. But over the years there has been a steadily growing deluge of letters – both to myself and to the editor of the Independent – in which readers, more thoughtful and more despairing than ever before, plead to know how they can make their voice heard when democratic governments seem no longer inclined to represent those who elected them. How, these readers ask, can they prevent a cruel world from poisoning the lives of their children? ‘How can I help them?’ a British woman living in Germany wrote to me after the Independent published a long article of mine about the raped Muslim women of Gacko in Bosnia – women who had received no international medical aid, no psychological help, no kindness two years after their violation.