Полная версия:

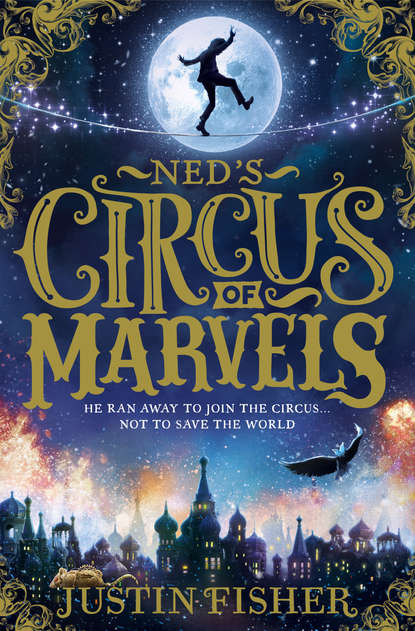

Ned’s Circus of Marvels

Copyright

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books 2016

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers,

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Text © Justin Fisher 2016

Cover illustration © Manuel Šumberac

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Justin Fisher asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008124526

Ebook Edition © 2016 ISBN: 9780008124533

Version: 2016-05-24

For C, the glue that binds my pages

And for L, G and L, my tiny pots of Ink

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1. A Birthday Wish

Chapter 2. Surprise

Chapter 3. The Greatest Show on Earth

Chapter 4. Kitty

Chapter 5. Lots & Lots of Marvels

Chapter 6. Whiskers

Chapter 7. The Present

Chapter 8. The Flying Circus

Chapter 9. Collision Course

Chapter 10. Mystero the Magnificent

Chapter 11. Behind the Veil

Chapter 12. Inside the Box

Chapter 13. Face-off

Chapter 14. Darklings

Chapter 15. Something in the Smoke

Chapter 16. A Prisoner

Chapter 17. Secrets and Lies

Chapter 18. Awakenings

Chapter 19. The Truth

Chapter 20. The Amplification-Engine

Chapter 21. French Steel

Chapter 22. A Single Grain of Sand

Chapter 23. Oublier and Co

Chapter 24. So Jump!

Chapter 25. Something in the Mirror

Chapter 26. Mr Sar-adin

Chapter 27. Edelweiss

Chapter 28. St Clotilde’s

Chapter 29. Mother’s Day

Chapter 30. Farewell

Chapter 31. Theron’s Keep

Chapter 32. Falling Star

Chapter 33. The Show Must Go On

Chapter 34. On Your Marks, Get Set …

Chapter 35. Annapurna

Chapter 36. Cold-hearted

Chapter 37. The Source

Chapter 38. The Final Curtain

Chapter 39. To Mend a Broken Heart

Chapter 40. Home

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Read on for a sneak preview …

About the Author

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

The building work at Battersea Power Station had been abandoned without warning. ‘SITE UNDER NEW MANAGEMENT’ billboards had been hurriedly put up years ago, with a small logo stamped across their tops, ‘OUBLIER AND CO’. The army of cranes, bulldozers and diggers lay silenced, their only visitors an occasional seagull and deepening bouts of rust. It was late and London was asleep. As always, the River Thames flowed quietly by, disturbed only by the odd houseboat and the occasional taxi making a final drop off before heading home.

It started as it usually did. Deep in the bowels of the old power station, the air began to move. Behind a half-cracked mirror, water pipes trembled, inexplicably flowing backwards, inexplicably flowing at all. If anything could have lived down there, which it couldn’t, it would have run. Only the building’s four vast chimneys could see how the shadows turned and twisted, before revealing a mud-splattered, silver-haired nun.

Sister Clementine was tired, tired of running, tired of always being afraid. Ever since she’d agreed to carry the message, they’d had her scent. No matter how well she’d hidden, no matter what tricks she’d used, they’d always found her. Her chest was tight and her legs ached from the chase. She had to think fast; any minute now and they’d be on her. She couldn’t outrun them, especially not the little one. By the time she made it to the fence, they’d have her, and if they had her, there was no hope of keeping quiet. No one ever kept quiet.

Looking out towards the river, she saw a sliver of hope. If she could make the crane in time, she might get high enough to go unnoticed. She climbed the ladder quickly and quietly, her robes perfect cover under the pitch-black sky.

But Sister Clementine did not go unnoticed. Finally at the crane’s arm she slowed enough to hear them. The same two men that had tracked her since the beginning, one short and barrel-chested, the other impossibly tall. They were studying their new surroundings carefully. The shorter man sniffed at the air’s unique aroma, while the tall man’s pin-sharp eyes scanned the horizon. Their kind might usually have been nervous, afraid even of being on land owned by Oublier and Co. But not these men. It was not their job to fear, but to be feared. They were the things that went bump in the night.

In no time they had zeroed in on their target. They moved fast, the tall one climbing with all the skill of a spider while the other charged with the excitable brute strength of a predator nearing its prey.

Sister Clementine moved further down the crane arm as her assailants reached the top.

“Gimme the co-ordinates, Clementine. Jus’ two sets o’ numbers and you go free,” said the tall man, in a thick American accent.

Clementine’s foot slipped, finding only air instead of metal. There was nowhere else to run. The tall American pulled a revolver from his hip, aiming it squarely at the woman’s head.

“Don’t kill her, just wound her; she’s worth nothing if she can’t talk,” snarled the barrel, edging down the crane’s arm towards her.

The nun looked down at the void of black, before closing her eyes for one last prayer.

“He wants the child, Clementine,” said the American.

But the nun’s mind was already made up.

“Lord, make me an instrument of your peace.

Where there is hatred, let me sow love …”

Where there is darkness, joy …”

“WHERE IS SHE?” barked the barrel, almost upon her now.

Sister Clementine opened her eyes and smiled.

“Go to hell.”

She stretched out her arms like wings and pushed hard on the crane beneath her, launching herself into the air. There was no hard crunch of concrete below, only a splash as she landed in the River Thames’s waters. The tall American waited, peering into the darkness, before firing a single perfect round.

“Did you get her?” asked the barrel.

“Have I eva missed?”

A Birthday Wish

“Hinks?” said Mr Wilkinson.

“Yes, sir.”

“Well done. A plus. Johnston?”

“Sir.”

“Not a bad B, Johnston. Widdlewort?”

“It’s Waddlesworth, sir.”

“Yes, yes of course it is. C again, Widdlewort.”

The subject didn’t matter. Ned Waddlesworth always got a C. Not a C plus or minus, nothing with any particular character, just your average, everyday C. He was an unremarkable-looking boy too, with light brownish sort of eyes, and hair that was neither long nor short, styled nor loose, brown nor blonde. His hair was, quite simply, there. Ned wasn’t tall or short, chunky or particularly thin. At school Ned wasn’t in the clever classes, nor did he slouch at the back. Ned, like his hair, was just: there.

Teachers barely noticed him arrive at his new schools, or leave again a few months later. He never got to try out for any of the teams and, until recently, was never around long enough to make any friends. Unnoticeable Ned slipped through the cracks, again and again and again.

His father, Terry Waddlesworth, had once been an engineer. He’d retired from that profession before Ned was born and now sold specialist screws for a company called Fidgit and Sons. “Best in the business”, according to Terry. The job had them move around the country often, sometimes with little or no warning, and was, as far as Ned was concerned, the reason for all his woes. But that wasn’t the only issue Ned had with his father. Terry Waddlesworth had a profound dislike for anything risky or “dangerous”, which meant he rarely left the house unless going to work. He was interested in only three things: amateur mechanics, watching quiz shows on the telly, and Ned’s safety. It did not make for an environment that let growing boys …‘grow’.

They lived at Number 222 Oak Tree Lane, in Grittlesby, a suburb south of London, famed for its lack of traffic, quiet streets and generally being entirely unremarkable. It was the longest they’d stayed in any one place though, and Ned was just happy to have finally managed to make some friends, Archie Hinks and George Johnston from across the road. Despite his father’s best efforts Ned was growing roots.

“So, last day of term,” said Archie as they all headed home from school.

“Yup,” agreed Ned happily.

“And it’s your birthday,” said George. “Major event, Ned, major event. We’ll need to meet up tomorrow for the ceremonial exchanging of presents, of course.”

It would be Ned’s first birthday with the added bonus of friends. The fact that they’d even thought of gifts came as a genuine shock.

“You got me presents? Actual presents?”

“Well, I wouldn’t get too excited. Arch got me batteries last year, wrapped up in old newspaper.”

“They still had a little juice left in them,” grinned Archie.

“Your dad got anything planned?”

Ned’s face darkened.

“My dad? Doubt it. He’s not great with stuff like that. Last year we stayed in watching cartoons. I mean, cartoons! We never go anywhere. It’s like I’m made of glass or something, like he thinks the world was made to break me.”

“Cheer up, Widdler, least he cares, right?” said George.

“I know, I know …” sighed Ned.

At Ned’s gate they said their goodbyes and agreed to meet up after lunch the following day.

Ned opened the door of Number 222 and headed for the kitchen, weighing up the choice between another one of his dad’s microwave meals, or a jam sandwich. The sandwich won.

“Hi, Dad,” he called as he passed the living room.

“And the answer is – Eidelweiss,” chimed the TV.

“Dad?”

“Ned, is that you?”

“No, Dad, it’s one of the millions of visitors you get every day.”

Terry Waddlesworth walked into the kitchen, wearing the kind of tank top you could only find in a charity shop and looking unusually dishevelled.

“Neddles, I was starting to get worried.”

“Oh come on Dad, you’ve got to stop. I sent you the obligatory ‘I’m alive’ text message fifteen minutes ago and I came straight home because of tonight …”

“Because of …?” Terry was now staring through the kitchen window, and out on to the street.

Ned’s heart sank. His dad was like a satellite link when it came to knowing where his son was, but remembering anything else was often problematic. He had a habit of getting … ‘distracted’.

“You didn’t forget … did you?”

“Forget what?” asked Terry, his focus now back in the room.

“The large pile of presents and the party you’ve planned, you know, the one OUTSIDE the house, FOR MY BIRTHDAY?” said Ned, now certain that there’d be neither.

Terry’s eyes started to go a little watery and he pulled Ned in for a large hug.

“You all right, Dad? You’re not thinking about her again, are you? You know it only makes you sad.”

“Not this time, Ned, I promise. She would have loved it though. Our little boy, thirteen years old. Who’d believe it?”

“We said we wouldn’t talk about her today, Dad … and I’m not a little boy, not any more!”

“So you keep telling me.”

“I wouldn’t have to if you just let me … be,” muttered Ned, through gritted teeth and a faceful of his dad’s shirt.

“I know.”

“Dad?”

“Yes, son?”

“You can let go now.” And Ned didn’t just mean with his arms.

Ned’s dad released him at last. “I didn’t forget, son,” he said, producing an envelope and a badly wrapped present no bigger than the end of his thumb and handing them over.

Ned smiled, turning over the tiny package in his hands. “Please tell me this isn’t, like, really rare Lego. Because we’ve built just about everything you can with the stuff and I am seriously, like totally too old for it now.”

“No, Ned, it’s actually a bit rarer than that, but you’ll have to wait till tonight to open it. I do have a surprise for you though. We’re going to the circus. It’s on the green; the tickets are in the envelope.”

Ned would have loved the circus a few years ago, but he was thirteen now, and thirteen-year-olds had the internet, and cable TV and, more recently, friends. Still, any Waddlesworth outing outside the house was worth encouraging.

“Great … I love the circus,” he managed, with all the enthusiasm of a boy that still loves his father just a little bit more than the truth.

“Put them in your pocket, son. I’ve got a bit of a work crisis on. An old colleague of mine … she’s … she’s in a pickle, and I have to go and help her out, but I’ll be back later. We need to have ourselves a little talk before the show. Stay indoors till then, OK? You’ll love the circus, Ned. There’s nothing quite like it.”

Terry Waddlesworth didn’t usually mention “colleagues” and had never had a work crisis, at least not as far as Ned could remember. What worried him more were his dad’s shaking hands, as he went to pick up the keys.

“Dad, are you sure you’re OK? I hope this isn’t about moving again, because …”

But his father was already out the door, double-locking it behind him before marching off down the drive, and Ned was talking to himself.

Ned took his sandwich up to his room and looked around him. Everywhere a mess of abandoned projects lay scattered. Things he and his dad had started building, or were in the process of taking apart. The largest by far was a scale model of the solar system, every planet recreated from a mass of tiny metal parts and their corresponding screws. What made it different from more ordinary construction sets was that the planets actually orbited the sun, or at least they would, when Ned finally got round to finishing it. However, Ned’s new friends, all two of them, meant that he had less time for the compulsory Waddlesworth hobby, besides he was rarely challenged now by the things his dad wanted them to make. Plus he was starting to think that maybe building model sets with your dad was a little geeky anyway.

He didn’t have the heart to tell his dad though. It had always been their thing, but as Ned had got older he’d come to realise that Terry had a disproportionate obsession with it, as if any problem, any issue that life threw in their direction, might be answered by something found within the folds of some manual.

Ned was fed up with plans, with diagrams and instructions. “Don’t do this”, “don’t go there”, “make sure you call or text”. Much as he loved his dad, Ned wanted freedom, wanted to try life without a manual or his dad’s overprotective ways.

Ned sat down on his bed. Whiskers was lying on his pillow as usual and looked like he might be asleep, though Ned could never really tell. The old rodent had the uncanny habit of sleeping with at least one eye open.

Ned’s mouse never slept in a cage, barely moved unless you were looking at him and in all the years they’d had him, Ned couldn’t remember ever seeing him eat. According to Terry, he preferred dining alone.

“All right, Whiskers?”

The mouse didn’t move.

“Yeah, Happy Birthday to you too.”

He lay down beside him and thought about Terry. Something was making him particularly jumpy. And annoying as his dad could be, Ned did not like seeing him upset.

Ned was pretty sure his dad’s jumpiness had started on Ned’s very first birthday. Olivia Waddlesworth – Ned’s mum – had gone out to buy a candle for their son’s cake when she’d lost control of her car. In his grief, Ned’s dad had destroyed all the photos he’d had of her. Ned didn’t have any other relatives so everything he knew about his mother had come from his father’s memories. He’d described her in detail so many times over the years; the flecks in her eyes, the tint of rose her cheeks turned when she was embarrassed or cross. But it was who she’d been inside that made Terry’s eyes fill with tears. According to Ned’s dad, she had been kind and fierce at the same time. She would go out of her way to help a stranger, was passionate about the world around her, and had never told a lie, ever.

Ned stared at the photo frame on his bedside table. It was worn with both love and age, even though it was completely empty. Ned always made a wish on the night of his birthday and though he knew it would never come true, he always wished for the same thing: a photo of his mother.

And so, as he did every year, Ned made his birthday wish and waited for something to happen. But this year, unlike every other, as Ned closed his eyes and for a moment dozed off to sleep, something actually did.

***

Elsewhere, a tracker in a long, wax trench coat looked out across a forest. He had been there before. The beasts he hunted often used the old part of the wood, the part where shadows still moved with a will of their own, the part where one could hide, even from the hidden.

But this beast had grown too greedy, ventured too far, and now it had come under the watchful eyes of the Twelve and Madame Oublier. They would not allow it to continue. The two men stood beside him, with their matching pinstripe suits and carefully combed hair, had been watching this place for some time. When they were quite sure, they had called for the tracker, him and his animals. The hawk was his eyes, the lions his teeth, and the rest the tracker did himself. One of the pinstripes checked his pocketwatch, while the other made notes in a leather-bound book.

They needed to catch the haired one tonight before it could do more harm. In the branches above, the tracker’s bird called out to him.

“Lerft, roight … go!” the tracker breathed in a heavy Irish whisper.

His lions padded forward and in a moment were in the darkness and out of sight. The pinstripes nodded and he left them at their posts. His breathing steadied. Out here there was no time to be scared; fear could kill you as quick as claws.

Crack.

A broken branch, somewhere in the distance.

Crack. Crack.

Another and another.

The tracker paced forward, low to the ground. In a clearing in front of him a man sat by his tent and cried.

“Niet, niet,” moaned the tourist.

The beast circled him, growling, claws at the ready, saliva dripping from its hideous fangs.

The beasts were never found this far across the border. There were treaties with their kind written in blood, an oath as ancient as the forest it now walked. But something had changed, something had made them bolder, and this one was crazed with a hunger only the tourist and his warm, oozing blood would satisfy.

The boy pulled the silver from his pocket. A delicate chain could be as strong as a cage if handled the right way. He whistled to his lions. The beast was big and he was going to need them.

Surprise

Ned had been having the exact same dream for weeks now. It started with grey. No sound, no texture, just a wall of pure grey. But the grey had a way of turning in on itself, of tumbling and changing, till a shape would emerge, boldly lumbering towards him to the rising brum brum brum of a deep bass drum. The shape scared Ned. It was large and indistinct and heavy-breathing. But today the dream was different. Today he could see the shape as it truly was.

The shape was an elephant with pretty white wings. The animal was ancient and also had terrible breath. He knew this because, as the drumming got louder, it started to lick his face.

Ned found that there were moments, between being asleep and awake, when sounds and senses were stretched, altered. The ringing of an alarm clock might become a siren in a dream. Often it was hard to tell what was dream and what reality, and so it was as the licking from the elephant changed to the prodding of Whiskers’ snout on his cheek, as if the little rodent were trying to wake him up.

Ned opened his eyes. He must have been asleep for hours because it was now dark outside. So it had all been a dream. And yet, the drumming had not stopped, or at least, had become something else, some other strange sound. A sound that Ned instantly knew was bad before he had any idea what it might be, because the hairs on the back of his neck prickled, and the nails on his fingers felt tight.

It seemed to be coming from downstairs. Short laboured scrapes, one after another, then a pause.

“Dad?”

The scraping continued. Whiskers scampered off the bed and sniffed at Ned’s door. Dad had always joked that he made the perfect guard dog. Too small to need a walk, but with the hearing of a bat.

“Dad …” Ned shouted, “if this is a birthday surprise, it’s not very funny.”

There was no reply. Ned opened his bedroom door and cautiously crept down the stairs, closely followed by his mouse. The scraping was coming from the sitting room’s patio doors. Something outside was trying to claw its way in.

Ned’s first reaction was to run, and Whiskers, who was already squeaking noisily by the front door, was clearly of the same mind, but Ned’s curiosity had taken a hold. He turned, inching his way towards the sitting room, and was about to flick on the light switch when he saw something that made his blood turn cold. Standing in the glass doorway, lit up in the cold glow of the garden’s security lights, was the scariest sight he’d ever seen.