Полная версия:

The Boy from Nowhere

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2015

FIRST EDITION

© Gregor Fisher and Melanie Reid 2015

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2015

Front jacket photograph supplied by the author, background © Shutterstock.com

Cover quote reproduced with kind permission of The Telegraph © Michael Deacon, The Telegraph

All picture section photos provided by Gregor Fisher except where indicated.

The Scotsman extract © The Scotsman

Nancy Banks-Smith/Guardian extract © Nancy Banks-Smith

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein, the publishers would like to apologise for any omissions and will be pleased to incorporate missing acknowledgements in any future editions.

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Gregor Fisher and Melanie Reid assert the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 978008150433

Ebook Edition © October 2015 ISBN: 9780008150464

Version: 2015-11-20

Dedication

To my mother

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

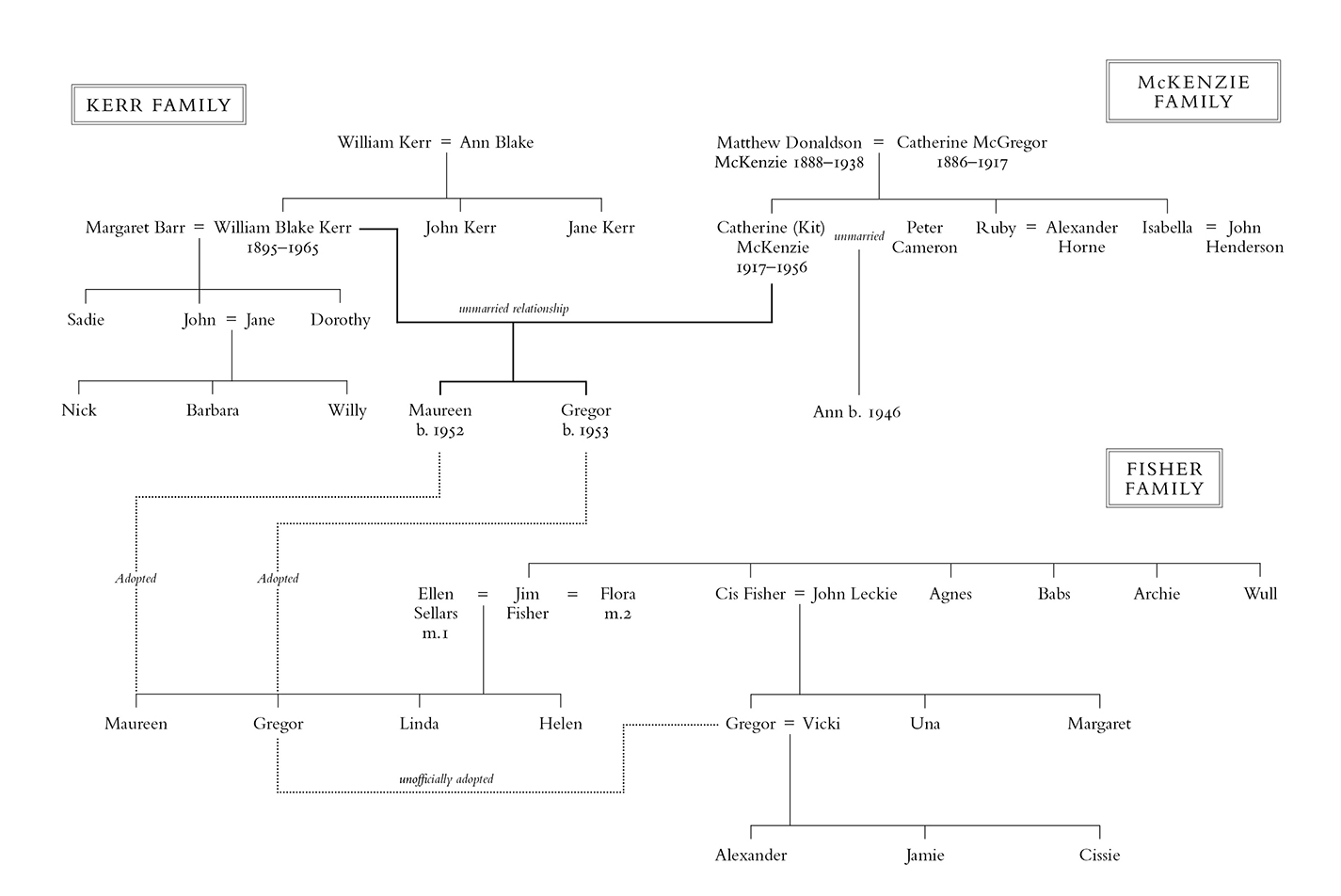

Family Tree

Prologue

1 The Curly-Haired Boy in the Corner

2 Fisher, You’re Playing Pooh-Bar

3 You Don’t Know Me But I’m Your Sister

4 I’d Like You to Move to the Colour Blue

5 Eat the Ice Cream While It’s on Your Plate, Ladies and Gentlemen

6 Aunt Ruby and the Red-Chip Gravel Drive

7 The Poem in the Wallet

8 Kit

9 The Deil’s Awa’ Wi’ the Exciseman

10 Evening Comes, I Miss You More

11 Rab C. Nesbitt

12 A National Treasure

Epilogue

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Picture Section

About the Publisher

Prologue

‘Time shall unfold what plighted cunning hides’

King Lear: Act I, Scene I

A story has to start somewhere, so let it begin with two men, strangers to each other, but with lives that will run in parallel. Matthew Donaldson McKenzie and William Blake Kerr were born in Scotland in 1888 and 1895 respectively. Both survived the slaughter of the Somme, married the same year, had children the same age, found jobs and sought to make their way in the world. Eventually their paths would cross, with far-reaching consequences.

Matthew, the elder of the two, returned from the trenches to witness his sick wife give birth, and two days later he was to see her die. He was left with three motherless children, serious trench fever and a damaged leg.

In 1921 he re-married, to a young dressmaker, and took a job at a whisky distillery in a small village in central Scotland. He moved his family into a tied house – one of the houses under the hills. Remember this place, for we shall return here many times.

William, the younger soldier, returned from war scarred by the sight of filth and disease. Educated and ambitious, he got a job as a customs and excise officer, married and started a family. In 1928 came the move upon which this story hangs. William took a job overseeing three whisky distilleries within a mile of each other. One of them was where Matthew worked.

So the lives of the two men converged at the foot of the stern Ochil Hills. The factory engineer and the feared exciseman were neighbours, briefly, in the houses under the hills, and then work colleagues for the next decade. We have no proof, for time hides such tracks, that they were friends, but it is inconceivable they were not acquainted. William saw Matthew’s small daughters playing outside, on the stone steps or on the drying green. They were much the same age as his own little ones.

Victorians by birth, William and Matthew were God-fearing men of status, pillars of the community. One was a government law officer, the other a church organist and teacher at Sunday school. Freemasons, they abided by the social rules of a different age. One would die soon, but tragedy was to stalk them both. And one day scandalous events would unite them in a long-buried tale of betrayal, love and survival.

Let’s ask, just this once. Is everything random, or do we believe in fate?

CHAPTER 1

The Curly-Haired Boy in the Corner

‘I have always depended on the kindness of strangers’

Blanche DuBois in Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire

Thump.

Pause.

Thump.

Pause.

Thump.

Three thumps – never more, never less. No cheery ‘Hallooo!,’ no cry of ‘That’s me, Cis,’ just three dictatorial thuds on the bedroom floor with his foot. John Leckie wanted his breakfast. After a lifetime working the night shift, this was the signal to his wife in the kitchen below to say that he had woken up. It was 5pm, and Cis would prepare tea, toast and marmalade and take it upstairs. Mr Leckie ate upstairs and then came down: a tall, stern, well-built man, ready to go to work. The child, sitting silently, for it was best to keep quiet, would look up and see the great long legs of his boiler suit appearing down the stairs.

John Leckie was, it’s fair to say, as much a creature of routine as he was a man of few words. There was no conversation. He put a long, dark trench coat over his overalls, clapped his grease-stained engineer’s bonnet on his head and picked up the lunchbox Cis had prepared earlier. His lunch, his ‘piece’, was a thing of precise wonderment. It stayed exactly the same for nigh on 50 years: an ancient little Oxo tin containing sugar and loose tea, mixed before it went in, and cheese sandwiches in waxed bread paper, made with the well-fired top of the loaf. John Leckie was as set in his ways as he was undemonstrative. Leckie would nod to his wife and leave for the night shift in the great engineering works in the city. Nor were things much different when he returned home in the morning, weary and grimy. He came in, said little or nothing, took off his overalls, ate the meal Cis had prepared for him and climbed the stairs to bed. Soon it would be time to bang on the floor again for breakfast. Such was the unflinching, unchanging traffic of his life.

At weekends, John Leckie, in an old shirt and trousers and tank top with holes in it, would sit, not in an armchair but on a wooden slat-backed kitchen chair by the fire, his legs spread wide on the hearth, both hugging and hogging the heat. It was always cold in the 1950s. He would spend hours sitting there, hour after hour, in his own silent, still world, staring at the fire. No radio. No books. No conversation. He ignored anyone else who might be in the room. On the mantelpiece were his smoking paraphernalia, neatly arranged – a box of Capstan untipped full strength and the occasional half-smoked cigarette, extinguished early and saved. He would take the tobacco out and re-roll it. There were no matches – he made tapers from tightly rolled sheets of newspaper. When he stood up to smoke, which was frequently, he lit the taper from the fire and put it to the cigarette. The taper was carefully stubbed out and propped at one side of the fire to be re-used. He’d smoke his cigarette standing over the fire, and then sit down again. Occasionally he coughed. And if he needed to fart, he simply lifted one cheek of his backside and farted. No apologies. No glance around. ‘This is my house,’ announced the fart. ‘I’m the main man here.’ It was a thing of wonder to the little boy who observed. And Mr Leckie would continue to sit there, legs astride the fire, coal bucket sitting beside him. Eventually the fire would start to burn lower.

‘Cis,’ he would call in the direction of the kitchen.

Not a question, an order.

‘Uh-huh?’

‘Coal.’

And she would leave off what she was doing and come through to load coal upon his fire to keep him warm, while he sat there, unmoving. If he did speak, when she had done as he asked, it would only be to criticise the quality of the fuel she had put upon the fire.

‘There’s too much dross in that.’

The small boy remembered the day he arrived at John and Cis Leckie’s house, at the tail end of 1957. It all seemed so simple, back then. He was only three years old and Cis was his mother. Of this he had no doubt. He remembered the day he arrived there because it was snowy and they drove him up to where she lived, at the very top of the hill. He needed a pee and they had to stop the car on the slope. He remembered the pattern his pee made in the snow. He was a sturdy, smiley little chap with heart-melting blond curls and bright blue eyes. That first night, when her husband was at work, Cis carried the child outside to the loo because in 1950s Scotland most people still had outside toilets. The house sat high up to the south above Glasgow and it was a cold, frosty night – he could see the city lights twinkling and he thought he’d died and gone to heaven.

Safe, really safe, in Cis’s arms, looking at the lights.

He’s outside, pacing the decking, smoking a Gauloise. It’s Stirlingshire, Scotland, May 2014, and he’s on a flying visit from his home in France. Restless, wary, but eager, he really wants to talk. This has been a long time in the brewing, more than 60 years.

‘It’s really quite complicated, my story,’ says Gregor Fisher, actor, comic legend, man o’pairts. He pauses. ‘I just remember thinking that it was like trying to sort out a pile of spaghetti, or finding the ends of a tangled ball of wool. I didn’t know how to get to the bottom of this, or if I ever would, actually.’

It was a great place to grow up, that house at the edge of the village of Neilston in Renfrewshire, where there was countryside, animals, freedom, friends, mischief – affection and laughter. The family had an acre of land, once a market garden, up there on the hill, and the new child was the prince of all he surveyed. Some would say kindly that it was an eccentric house, others, more judgemental, that it was like Steptoe’s yard. Hens pecked around the back door, the odd goose waddled across the yard, a friendly old dog mooched. Primitive but of its era, the kitchen housed a deep Belfast sink that had a big, wooden step on the floor in front of it, so that Cis, who was not much more than five feet tall, could reach into the water. There was also a very old black range, with a built-in oven and hob. Later, in a nod to the 1960s, it would be taken out and replaced by a Baby Belling: a two-ringed cooker. In the living room was John Leckie’s open fire, with chipped tiles around it and a back boiler to heat the water. The fire was his territory; Cis stoked it, but he controlled it. It heated the house and provided any hot water there was. You got scrubbed in the big sink in the kitchen but you had to book a bath and they didn’t happen very often.

And if a bath was deserved, Cis used the poker to flick the lever at the back of the fire so the heat would be diverted to the boiler. At night she would load the fire with dross, or slack – the powder left at the bottom of the coal bunker – to keep it going, and it was her job to revive it first thing in the morning before anyone else was up. There was no other heating, but nobody ever thought there was anything odd about that, it was just the way it was. You came down in the morning, you got dressed in front of the fire. Sometimes Cis would stand, back to the flames, and lift up her skirt behind her to get a heat. A fleeting luxury.

‘Ah, that’s nice!’

Back then Scotland was a thoroughly tough country. It’s hard for us, from the comfort of the twenty-first century, to grasp just how tough it was. The gap between rich and poor was vast. As the Historiographer Royal, T. C. Smout, put it, simply and bluntly, the expectations of the working class were a hard life, a poor house and few material rewards. And, we can add, an early death. Basically, this meant 85 per cent of the population. By the 1950s, things were starting to improve, but everything was relative. John Leckie’s family, it must be said, were much better placed and more prosperous than many. They owned their sturdy, detached stone-built house; they could grow food and keep poultry to supplement their diet. Nevertheless, life, for them all, was a serious business. In working Scotland, pre-antibiotics, pre-welfare reform, you didn’t ask for anything. You sought to survive.

Gregor Fisher, the little boy with the winning blue eyes, landed lucky. Here, his was to be a stable childhood, in a society marked by thrift, hard work, regular church-going and what today’s children would regard as sensory deprivation, if not neglect: no television, few toys or holidays, even fewer luxuries, old-fashioned rules of discipline. Waste was unheard of, everything old. Wooden furniture. A 1930s brown sofa with a lever that, when pulled, lowered one end, turning it into a daybed. His new mother’s wooden carpet sweeper, circa 1925, with metal wheels, did its best on the old rugs laid on top of the linoleum floor. ‘Wax cloth’, his mother called the lino. There was a single light bulb hanging from a wire in the middle of the living-room ceiling; if you left it on when you went out of the room there was hell to pay. Always there was a dog that his mother was looking after for some old lady or other who was unwell; or somebody had died and left a dog and Cis, out of the goodness of her huge heart, would take the creature on.

She had a soft spot for animals and she loved her hens. There were lashings of fresh eggs; Gregor remembers yolks like Belisha beacons. At certain wintry times of the year the hens were invited in the latch door at the side of the house and took up residence in the kitchen. A hen that was sitting on eggs, or a nest of chicks, would be kept either side of the range in a cage, and when the chickens got bigger and it was still cold outside, they would perch on the top of the kitchen door. Cis would put sheets of newspaper underneath the door to catch their droppings, but woe betide anyone who forgot and came down in the morning with bare feet.

When Gregor arrived, John Kerr Leckie was 56, and Cis about 50. They had a grown-up family – Margaret, 29, who was a schoolteacher, and Una, 23, who was a school secretary. At that time, the daughters were unmarried and still living at home, but out working every day. The little boy slept at first in bed with his mother when John Leckie was away at work; he remembers the bliss of sleeping in the big, warm bed, safe in her arms, and then, in the morning, when she got up, he used to roll into the cosy nest where her body had been. That was the best moment of all. There in the cocoon he knew for sure that everything was right in the world. Before long, though, before he was old enough for school, his new sisters decreed he should have a room of his own. There was a deep walk-in cupboard upstairs, under the coomb of the roof, with an internal window into their bedroom. It was wide enough to fit a single bed in, so the girls papered it with cowboy wallpaper and after a couple of nights of protest – ‘I want to sleep with Mummy!’ – he realised having his own room was actually quite nice.

There was no heating in the bedrooms; horsehair mattresses on the beds too. No insulation in the roof or the walls. When it got really cold, coats were piled on top of layers of blankets. Gregor had so many blankets he was riveted to the bed with the weight, and piled on top of them was a moth-eaten fur coat of his mother’s to keep him even cosier.

We forget how events of the twentieth century shaped lives, altered personalities. Conditioned by decades of consumerism and relative affluence, we are fast losing the ability to grasp how little ordinary people in those days possessed. Cis and her husband had lived through the Great War, the Depression and the Second World War. Prudence and austerity had defined their lives, were set in their bones.

In an era when people aged fast, where no glossy magazines existed to proclaim that 50 was the new 30, Cis and John Leckie looked and dressed like Gregor’s grandparents. It meant nothing to him. In the early days he did not understand that Cis was physically too old to be his birth mother. Why should he? He was too busy surviving on instinct, this child who was as pretty as pie. Butter wouldn’t melt in his mouth, he was quite simply the curly-haired boy in the corner; his life revolved around him. He knew his name was Gregor Fisher and Cis Fisher was his mother, except she was married to John Leckie, so she was called Cis Leckie. She was still his mother, nevertheless. He called her Mum, that’s just how it was. There were some unexplained things when he was growing up, but he didn’t ask any questions, he just accepted that was the way it was. As far as life was concerned, he and his mother were. He knew she was different from his pals’ mothers, but he didn’t care. What mattered was that she adored him. He had what he craved; he was content. Looking back, he realises just how lucky he was to find her – ‘Like so many things in my life, it was meant to be.’

They brought out the joy in each other. He and Cis would constantly set one another off laughing. They laughed when she put him to bed at night, giggling about all kinds of nonsense; they would sing songs and do silly things together. She gave him unconditional love and attention. Maybe she just had a bottomless love for waifs and strays. Whatever the reason, her love saved Gregor Fisher, forged him and still sustains him. He openly acknowledges that he couldn’t live without what he got from her, nor would he have achieved what he has. And today, when he talks about her, it is the closest he comes to tears.

Cis can be described as an ordinary, extraordinary woman, or perhaps an extraordinary, ordinary woman. She was just one of hundreds and thousands of wee West of Scotland ladies who were the cement and the oil and the glue and the lifeblood of their families. Every day she wore a wrap-around pinny and coiled her long hair in a bun under a hairnet. Her red hair was going grey. She had a jam jar with red hair dye in it, and Gregor remembers watching her dip her comb in it and spread it into her hair, then shape it into a bun. Her diminutive size belied her determination and strength of personality.

Cis was a full-time housewife. The only time she sat down, Gregor remembers, was with him on her knee to listen to Listen with Mother on the wireless or when she read The People’s Friend. She carried the coal and went for the food, cooked, washed, cleaned, fetched her husband’s cigarettes. She got up early and set the fire before any of her family came downstairs. No one ever went hungry in Cis’s house, and food is a great way of doling out love. She had a routine of big family suppers late at night: scones, cheese on toast and cups of tea. The family could tell the day of the week by the main meal: one day they had stew, then there was mince, on a Friday there was fish. Every Friday afternoon Cis and Gregor, in the days before he went to school, would catch the bus to Shawlands in Glasgow to get Scotch mutton pies from Short’s in Skirving Street for Saturday and fresh butter in a pat from Henry Healy’s, the City grocer.

Cis’s sister, Aunt Agnes, conveniently lived in Shawlands too, in what the little boy considered rather an exotic, tenement flat. Best of all, she had a piano, which Gregor was mad for, and for him it was the highlight of a Friday afternoon, going thump, thump, thump on the keys, because somehow music was in his blood but he didn’t know it then.

So there was never any choice about what was for supper, nor were those the days of sweet potato with cumin and rocket and a poached egg on top. Plain food, plain lives, few expectations … there was no experimentation whatsoever. It was mince, stew, big pots of really good soup and baking. Gregor enjoyed his food. His mother made rhubarb tarts and apple tarts, she did a top-class fry-up and she also made the best shortbread he could ever hope to taste. Plainly, she and her sisters were a family of bakers, for Aunt Agnes had been at one time industrious enough to start up her own bakery shop.

But this was an extremely male-dominated society. Women like Cis, fathered by and wedded to the stern Presbyterian working men Scotland excelled in, were fantastically strong copers, but they kept their emotions in check. Life taught them not to expect too much. They kept house at a time before bathrooms or washing machines or detergents; they raised children on meals magicked from very small incomes; they toiled from early to late as slaves to men like John Leckie – and he was a saint compared with most men, for he did not drink. Women like Cis were not schooled in any kind of delicate niceties and displays of emotion; kissing and hugging were unheard of. Hers was a loving household but one devoid of displays of physical affection. Until her old age, even a pat on the head was a very unusual thing.

Decades later, when Gregor went into show business, everyone was hugging and air-kissing each other all the time – the whole luvvie thing. Recalling this, he flaps his hands in comic revulsion. ‘Christ, I couldn’t cope, I couldn’t bear it! It was like, “What are you doing? Get away from me! There’s a barrier here, can’t you see it? Come on, what’s going on? I’m a Scotsman. Please don’t do that, you’re making me feel very uncomfortable.”’

At the time, locked in the intensity of his one-to-one relationship with his new mother, Gregor had little or no concept of the needs of other members of the Leckie family. All children, but especially needy ones, are entirely self-centred. Instinctively, they manipulate the person who gives them most succour and affection. From his perspective, he clung to Cis for emotional and physical survival. Looking back, he realises he caused tensions but he now understands why.

I don’t think I was a very nice little boy. To be honest, I think I was a right little pain in the arse. Looked nice, you know, lots of nice blond curls and all the rest of it; nice to look at, but not nice to spend any time with – the little shit in the Ladybird shorts. I don’t think the rest of the family liked me very much because I was so desperate to gather in every bit of affection that Cis could give me.

Though loved and secure, he was at the same time an outsider who watched and remembered. When John Leckie was around it was best for Gregor to play in the corner. In the silence he absorbed and listened. The other male role model in his life at that time was Uncle Wull, a man every bit as eccentric as John Leckie, both of them rich fodder for the child who would one day put their idiosyncrasies to good use. Wull was a bit simple. Gregor liked him. Cis’s half-brother, he was much older and illegitimate – her mother had had a child out of wedlock that nobody knew about. Cis and her siblings didn’t know of his existence until much later, when Granny died, and he was then taken under Aunt Agnes’s wing. During the week he lived with her in town and went to work at the Parks Department in Glasgow; on weekends he always came to stay at Neilston to be fed and looked after by Cis.