Полная версия:

Resort to Murder: A must-read vintage crime mystery

PRAISE FOR TP FIELDEN

‘A fabulously satisfying addition to the canon of vintage crime’

Daily Express

‘Unashamedly cosy, with gentle humour and a pleasingly eccentric amateur sleuth’

The Guardian

‘Highly amusing’

Evening Standard

‘TP Fielden is a fabulous new voice and his dignified, clever heroine is a compelling new character’

Wendy Holden, Daily Mail

‘A golden age mystery’

Sunday Express

‘Tremendous fun’

The Independent

TP FIELDEN is a biographer, broadcaster and journalist. Resort to Murder is the second in the English Riviera Murders series featuring Miss Dimont.

For Laurel Wilson Voyager, forager

CONTENTS

Cover

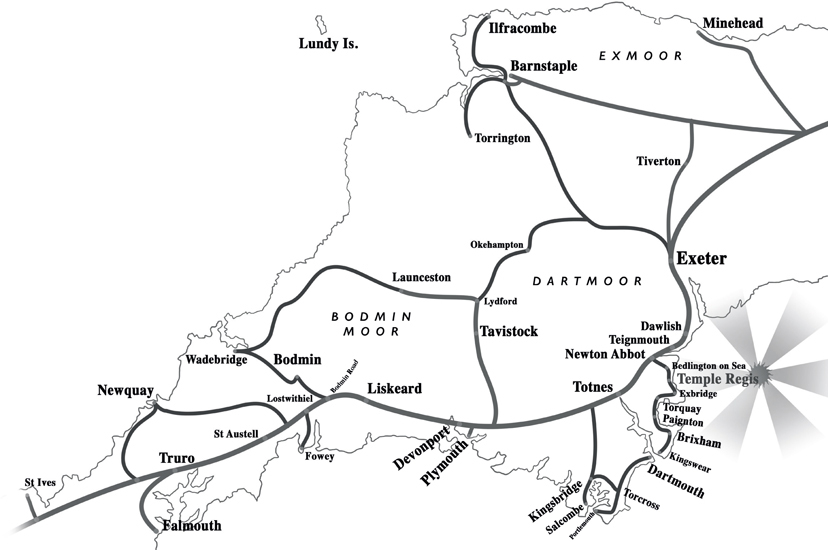

Map

PRAISE FOR TP FIELDEN

Title Page

About the Author

Dedication

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

TWENTY-FOUR

TWENTY-FIVE

TWENTY-SIX

TWENTY-SEVEN

Extract

Copyright

ONE

Pale aquamarine and milky like the waters of Venice, the sea moved slowly inland. The shoreline at Todhempstead welcomed the advance reluctantly, giving up its golden sands inch by inch, unwilling to concede a single yard of the most beautiful beach.

The body lay some way distant from the incoming tide, but sooner or later it would have to be moved.

For the moment, though, it lay there, surrounded by a frozen tableau – a small group of people immobilised by what lay at their feet. Death changes behaviour patterns, imposes a protocol of its own.

She was young, she was blonde, and she may have been pretty but for the hideous open wound that claimed half her face. Her dress was glamorous in an inexpensive sort of way, arranged around her decorously enough. It was still dry, a sure indicator it had not been here too long.

Frank Topham looked down with some discomfort. The long shallow beach had at its furthest end a high embankment, surely too far away for the victim to have fallen from and landed here. The injuries which claimed her life were too severe – that much was evident – for her to have walked or crawled to her final resting place, yet there were no footprints around the body apart from those made sparingly by the small group of eyewitnesses.

Nor was there any blood.

These contradictions jarred Inspector Topham’s usually tranquil state of mind, but were swept aside for the moment as he looked down on the wretched girl.

‘Twenty, I should say,’ he murmured to the two faceless acolytes standing at his shoulder.

‘No shoes,’ said one.

‘No handbag,’ replied Topham.

The other lit a cigarette and looked up at the sky. He didn’t seem terribly interested.

Whatever passed next between these custodians of the peace was drowned by the arrival of the up train from Exbridge, a billowing, grunting triumph of the steam engineer’s art, slowing as it made its long approach into Todhempstead Spa station.

‘Better get her away,’ Topham said to the police doctor. The man on his knees looked over his shoulder at the advancing waves and nodded.

‘No evidence,’ said Topham wretchedly. ‘No clues. We’re moving the body and there’s no clues.’

Taking his cue, the second man moved vaguely away and came back. ‘Tizer bottle.’

‘Is the label wet?’ asked Topham without even looking at it.

‘Yer.’

‘Chuck it,’ snapped the inspector. ‘No use to us.’

He moved swiftly off to the slipway where the car was parked, not wanting the men to see his face. There had been too many deaths back in the War, but wasn’t that why he had fought? So there wouldn’t be any more? It was a man’s job to die, not a woman’s.

For a moment he turned to look back at the scene below. The dead body claimed his focus, but, beyond, it was as if nobody cared that the world had lost a soul this morning. In the distance two sand-yachts raced each other across the broad beach, and overhead an ancient biplane trailed a long banner flapping from its tail. Smith’s Crisps, according to its message, gave you a wholesome happy holiday.

Far in the distance he could see a solitary female figure, dressed in rainbow colours, standing perfectly still and looking out to sea as if what it had to offer was somehow more interesting than a dead body. It was as if nobody cared.

Inspector Topham got in the car and pulled out on to the empty road. He reached Todhempstead Spa station in a matter of minutes, but already the Riviera Express was pulling out, heading on towards Exeter at a slow roll – huffing, grinding, thumping, clanging. He could get it stopped at Newton Abbot to check if there was evidence on the front buffers of contact with human flesh from the downward journey, to quiz the train guard and the driver. But they’d all be back again this afternoon on the return trip, and he doubted, given the distance of the body from the railway embankment, that this was a rail fatality. Though, with death, you could never be sure about anything.

As he drove back to the Sands, his eyes lifted for a moment from the road ahead. It was already mid-June and the lanes running parallel to the beach were bursting with joy at summer’s arrival. Though the bluebells and primroses had retreated, the hedgerows were noisy with young blackbirds testing their beautiful voices, while, beneath, newly arrived wild roses and cow parsley reached out, begging to be noticed.

How, asked the policeman, could anyone wish a young girl dead at this season, when hope is in the air and the breeze is scented with promise? His years in the desert, those arid wastes of death, might be long behind but still they cast their shadow. He drove down the slipway on to the beach, got slowly out, and nodded to his men.

‘Body away,’ said one.

‘Come on then.’

Topham removed his hat and got back in the car. His square head, doughty and in its own way distinguished, grazed the ceiling because of his ramrod-straight back. Despite the rising heat he still wore the raincoat he’d donned in the early morning when he got the call. He’d been too distracted by what he’d seen to take it off.

Too honest a man, too upright, perhaps too regimented in his thinking to see life the way criminals do, Frank Topham was both the very best of British policing and, some might argue, the worst. There was a dead woman on the beach, but if it was murder – if – the culprit might never be caught. No clues, no arrest.

No hope of an arrest.

The car approached Temple Regis, the prettiest town in the whole of Devon, and, as the inspector drove up Cable Street and over Tuppenny Row, his eyes took solace in the elegant terrace of Regency cottages whose pink brickwork blushed in the summer sunshine. Further down the hill he could hear the clanking arrival of the 10.30 from Paddington, its sooty steamy clouds shooting upwards from Regis Junction station. Life was carrying on as if nothing had happened.

Topham entered the police station at his regulation quick-march. The front office was empty apart from the desk sergeant.

‘Frank.’

‘Bert.’

‘Anything for the book?’ The sergeant had his pen poised.

Topham hesitated. ‘Accidental. Woman on T’emstead Beach.’

The other man gazed shrewdly at him. ‘You sure? Accidental?’

Topham returned his gaze evenly. ‘Accidental.’ He tried to make it sound as though he believed it.

‘Only I got a reporter in the interview room. Saying murder.’

‘Reporter?’ barked Topham nastily. ‘Saying murder? Not – not that Miss Dimont?’

‘Nah,’ said Sergeant Gull. ‘This ’un’s new. A kid.’

Topham’s features turned to granite at the mention of the press. Though Temple Regis boasted only one newspaper, it somehow managed to cause a disproportionate amount of grief to those police officers seeking to uphold the law. Questions, questions – always questions, whether it was a cycling without lights case or that unpleasant business with the curate of St Cuthbert’s. As for Miss Dimont …

To Frank Topham’s mind – and in the opinion of many other Temple Regents too – the local rag was there to report the facts, not to ask questions. So often the stories they printed showed a side to the town which did little to enhance its reputation. What good did it do to make headlines out of the goings-on the Magistrates’ Court? Or ask questions about poorly paid council officials who enjoyed elaborate and expensive holidays?

And how they got on to things so quickly, he never knew. What was this reporter doing asking questions about a murder? It was only a couple of hours ago he himself had clapped eyes on the corpse – how had word spread so fast?

‘So,’ said Sergeant Gull, picking up his pencil and scratching his ear with it, ‘the book, Frank. Murder or accidental?’

‘Like I said,’ snarled his superior officer, and strode into the interview room.

You can be the greatest reporter in the world but you are no reporter at all if people don’t tell you things. A dead body on the beach is all very well but if you’re out shopping, how are you supposed to know?

In fact Miss Judy Dimont, ferocious defender of free speech, champion of the truth and the thorn in the side of poor Inspector Topham, hardly looked like Temple Regis’ ace newspaperwoman this afternoon. As she ordered a pound of apples in the Home and Colonial Stores in Fore Street she might easily be mistaken for a librarian on her tea break: the sensible shoes, the well-worn raincoat and the raffia handbag made it clear that here was a no-nonsense, serious person who had just enough time to stock up on the essentials before heading home to a good book.

‘One and sixpence, thank you, miss.’

The reporter reached for her purse, smiled up at the young shop assistant, and suddenly she looked anything but ordinary. Her wonderfully erratic corkscrew hair fell back from her face and her sage-grey eyes peeped over the top of her spectacles, which had slithered down her convex nose. The smile itself was joyous and radiant – the sort of smile that offers hope and comfort in a troubled world.

‘Tea?’

‘Not today thank you, Victor.’ She didn’t like to say she preferred to buy her tea at Lipton’s round the corner. ‘I think I’ll just quickly go over and get some fish.’

‘Ah yes.’ The assistant nodded knowledgeably. ‘Mulligatawny.’

This was how it was in Temple Regis. People knew the name of your cat and would ask after his health. They knew you bought your tea at Lipton’s and only gently tried to persuade you to purchase their own brand. They delivered the groceries by bicycle to your door and left a little extra gift in the cardboard box knowing the pleasure it would bring.

‘I tried that ginger marmalade,’ said Miss Dimont, with perfect timing. ‘Delicious! In fact it’s all gone. May I buy some if you have any left?’

The assistant in his long white apron hastened away and, as she wandered over to the marble-topped fish counter, she marvelled again at the interlocking cogwheels which made up Temple Regis’ small population. Over by the coffee counter the odd little lady from the hairdresser’s was deep in conversation with the secretary of the Mothers’ Union in that old toque hat she always wore, winter and summer. Both were looking out of the window at a pair of dray horses from Gardner’s brewery, their brasses glinting in the late sunlight as they plodded massively by.

They’d all meet again at the Church Fete on Saturday, bringing fresh news of their doings to share and deliberate upon. While the rest of Britain struggled with its post-war identity crisis – move forward to the brave new world? Or go back to the comfortable past? – life in Devon’s prettiest town found its stability in the little things of here and now.

‘Do you have any cods’ heads? If not, some coley? And a kipper for me, please,’ just in case anybody should think she was reduced to making fish soup for herself, delicious though that would be!

It had been a perplexing day, and the circular rhythms of the Home and Colonial had a way of putting everything back in perspective. The Magistrates’ Court, the one fixed point in her week which always guaranteed to provide a selection of golden nuggets for the front page of the Riviera Express, had failed her – and badly. Quite a lot of time today had been taken up with the elaborate appointment of a new Chairman of the Bench, and that had been followed by a dreary case involving the manager of the Midland Bank and a missing cheque.

It shouldn’t have come to court – everyone has the occasional lapse! – and under the previous chairman the case would have been thrown out. But the Hon. Mrs Marchbank was no longer with us, her recent misdeeds having taken her to a greater judge, and in her place was the pettifogging Colonel de Saumarez, distinguished enough in his tweed suit but lacking in grey matter.

‘Anything else, miss?’

‘That’s all, thank you.’

‘Put on your account?’

‘Yes please.’

‘Young Walter will have it round to your door first thing.’

‘I’ll take the fish with me, if I may.’

The world is a terrible place, thought Miss Dimont, as she emerged into the early evening sunlight, what with the Atom Bomb and the Suez Crisis, but not here. She waved to Lovely Mary, the proprietress of the Signal Box Café, who was coming out of Lipton’s with a wide smile on her lips – how aptly she was named!

‘All well, Judy?’

‘Couldn’t be better, Mary. Early start tomorrow though, off before dawn. A life on the ocean wave, tra-la!’’

‘See you soon, then, dear. Safe journey, wherever you’m goin’.’

Miss Dimont walked down to the seafront for one last look at the waves. After the kipper, she would sit with Mulligatawny on her lap and think about the bank manager and the missing cheque. It had been a long day in court and she needed a quiet moment to think how best the story could be written up.

Things were less tranquil back at her place of work, the Riviera Express.

‘What about this murder?’ roared John Ross, the red-faced chief sub-editor. It was the end of the day, the traditional time for losing his temper. He stalked down the office to the reporters’ desks. ‘Who’s on it? What’s happening?’

Betty Featherstone clacked smartly over from the picture desk in her high heels. She was looking particularly radiant today though the hair bleach hadn’t worked quite so well this time, and her choice of lipstick was, as usual, at odds with the shade of her home-made dress. The way she carried a notebook, though, had a certain attraction to the older man.

Betty was the Express’s number two reporter though you wouldn’t know that if you read the paper – her name appeared over more stories, and in larger print, than Judy Dimont’s ever did, but that was less to do with her journalistic skills than with the fact that the editor liked the way she did what she was told.

You could never say that about Miss Dimont.

‘Who’s covering the murder?’ demanded Ross heatedly.

‘The new boy,’ sighed Betty.

The way she said it carried a wealth of meaning in an office that was accustomed to the constant stream of new talent washing through its revolving doors – in, and then out again. Either they were so good they were snapped up by livelier papers, or else they were useless and posted to a district office, never to be seen again.

‘Another rookie?’ snapped Ross, the venom in his voice sufficient to quell a native uprising. ‘When did he arrive?’

‘This morning,’ said Betty. She’d yet to try out her charms on the newcomer, but as ever she was willing to give it a try – he looked rather sweet, though of course those nasty photographers would be calling her a cradle-snatcher again.

‘Where’s your Townswomen’s Guild story?’ growled Ross, for Betty was not his cup of tea and her bouncy figure left him unmoved.

‘Here you are,’ she trilled, handing over three half-sheets of copy paper bearing all the hallmarks of an afternoon’s attention to the nail-varnish bottle.

‘A stimulating talk was given by Miss A. de Mauny at Temple Regis TWG on Tuesday,’ it began, one might almost say deliberately masking the joys ahead.

‘Titled Lady Rhondda and the Six Point Group it gave a fascinating account of the post-war women’s movement, taking in the …’

She could see Ross’s eyes glaze over as he read on. In truth, she’d found it difficult herself to stay awake during the earnest but dense peroration by the town’s only clock-mender. There weren’t too many jokes in her talk.

‘For … pity’s … sake …’ groaned Ross, a man ever-hungry for sensation. ‘We’re short on space this week. The Six Point Group? Naaaah!’

‘Husbands of TWG members advertise extensively in this newspaper,’ said Betty, primly parroting the words of her editor when she’d protested at having to attend the dreary event.

‘I’ll have to cut it.’

‘Do what you like,’ said Betty. Her mind was already on the evening ahead. A drink perhaps with that new reporter, the start of something new?

And maybe, this time, it could be for ever?

TWO

Miss Dimont sat in the public bar of the Old Jawbones, a beaker of rum on the stool in front of her, surrounded by a group of men – bulky, muscular, unshaven and with the occasional missing tooth – who roared their approval as she raised the glass to her lips and drank.

It was 10 o’clock in the morning.

This scene of depravity had an explanation but not one that could ever find the approval of her editor, the fastidious Rudyard Rhys. A stickler for decorum among his staff, he would shudder at the thought of his chief reporter behaving in so abandoned a fashion. In a filthy old fishermen’s pub! At ten o’clock in the morning!

Miss Dimont didn’t care. She shot a waspish remark at her fellow-drinkers and they burst once more into laughter. One more swig of rum and then, picking up her notebook, she moved slowly and almost steadily towards the door.

‘Whoops-a-daisy, Miss Dimmum!’

‘Don’t you fall down now, Miss Dimmalum!’

‘And doan fergit y’r turbot!’

The Jawbones was unused to entertaining female company at this hour, reserving its best seats for the men who filled their nets quickly and sneaked back into harbour for a quick one before breakfast. But there she was, a beauty in a haphazard sort of way, with her grey eyes, convex nose, beautiful smile and unmanageable corkscrew curls. The fishermen liked what they saw.

Miss Dimont emerged onto the street and took a deep breath of the fishy, salty air. Across the quay lay the rusty beaten-up old fishing vessel which had so recently put her life in peril. The memory made her sit down quite sharply.

‘Awright, missus?’ A handsome old seadog in faded blue overalls and battered cap came over and settled himself next to her.

His countenance was like a road map, all lines and detours, and his hands were ingrained with dirt. But he had charm – not like those men she encountered when she arrived before dawn to join the Lass O’Doune. She thought she’d never met such a band of brigands, strangers to the scrubbing brush and razor alike, unfamiliar with the finer points of etiquette.

By the end of her treacherous journey, though, they had acquired other attributes – they had become handsome. They had become warm, and kind. And they were undoubtedly heroes.

But it had not started well. ‘We were tol’ to expect a reporter,’ said the captain, Cran Conybeer, eyeing her with disfavour in the predawn darkness.

‘I am a reporter,’ snapped Miss Dimont, pushing her spectacles up her rain-spattered nose and standing ever so slightly up on her toes.

Captain Conybeer wasn’t listening. ‘We don’t ’ave wimmin aboard,’ he said firmly. ‘Send a reporter an’ we’ll take ’un out.’

Miss Dimont had experienced worse rebuffs. ‘You’ve just won the Small Trawler of the Year Award,’ she said, her words almost lost by the screeching of the davits as they hauled the nets up. ‘You’re the first Devon crew ever to win it. My newspaper has reserved two whole pages to celebrate your courage and skill, to tell Temple Regis how brilliant you are and – just as important, I’d have thought – to let your competitors know how much better you are at the job than they are.’

This last point hit home, but even so the captain remained reluctant.

‘Yers but …’

‘The article has to be written by the end of the day if it’s to get into next week’s newspaper. It’s 4.30 in the morning and there is no other reporter available to come with you on this trip.’

‘We doan allow wimmin.’

Miss Dimont slowly pushed back her hair and looked up into the captain’s wrinkled eyes, sparkling in the gas lamp which illuminated the ship’s bridge.

‘Perhaps this will help,’ she added quietly. ‘I was an officer in the Royal Navy – the Wrens, you would call it. I served my country and I served the sea.’

This last bit was not strictly accurate but it was enough for the wavering Conybeer.

‘Come on then, overalls on, we’m late as ’tis.’

And so, before the dawn light rose, the Lass O’Doune set out down the estuary and straight into a force nine gale – unseasonable in June, but that is the sea. The next four hours were a terrifying combination of chaos and noise, of unforgiving waves crashing across the decks and the ocean rampageously seeking the lives of those who sought to draw nourishment from it. Clad, pointlessly, in hooded oilskins – the sea had a way of finding its way underneath the stoutest protection within minutes – the men fought nature valiantly as they reeled in the nets and deposited their wriggling silvery spoils on the deck.

Fearless under fire, thought Miss Dimont, as she clung uncertainly to a rail inside the bridge – like soldiers in battle. Then, shouting to the captain, she weaved her way towards the deck so she could experience at first hand what his men had to do to make their living.

With a lifeline attached to her waist, she stepped out into the roaring, rushing hell and hauled on the nets alongside the other men. The job was not difficult, she discovered, it just required nerve and strength.

Arranged as a special demonstration for the press, the voyage out into the ocean lasted a mere three hours, though to Miss Dimont it seemed like four days. No wonder she’d found herself in the snug of the Old Jawbones with a jigger of rum in front of her!