Полная версия:

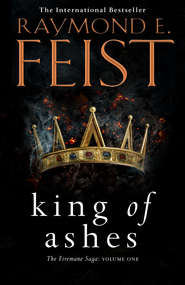

King of Ashes

RAYMOND E. FEIST

KING OF ASHES

THE FIREMANE SAGA: BOOK ONE

HarperVoyager, an imprint of

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Copyright © Raymond E. Feist 2018

Map © Jessica Feist 2018

Raymond E. Feist asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007264858 (HB)

Ebook Edition © April 2018 ISBN: 9780007290246

Version: 2018-03-08

This book is dedicated to the memory of Jonathan Matson.

He was perhaps the finest man I’ve ever known. His generosity, support, and affection went so far beyond any business relationship, he held me together more than once. He never judged; that was the heart of his wisdom, and the wisdom of his heart. His memory will endure and he is missed every day.

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

• Prologue •: A Murder of Crows and a King

• Chapter One •: Passages and Departures

• Chapter Two •: A Task Completed

• Chapter Three •: Dangerous Discovery

• Chapter Four •: New Considerations and an Old Friend

• Chapter Five •: A Parting and Trials

• Chapter Six •: Unequal Talents

• Chapter Seven •: An Incident on the Covenant Road

• Chapter Eight •: An Unexpected Change of Tide

• Chapter Nine •: A Hint of Things More Dire

• Chapter Ten •: In the Crimson Depths

• Chapter Eleven •: A Quick Instruction and Introduction

• Chapter Twelve •: Adrift and Alone

• Chapter Thirteen •: A Short Journey and a Strange Event

• Chapter Fourteen •: A Short Respite and Revelations

• Chapter Fifteen •: An Unexpected Visit and Rumours of War

• Chapter Sixteen •: Hints of Truth and Dark Designs

• Chapter Seventeen •: Unexpected Bounty and Sudden Danger

• Chapter Eighteen •: A Betrayal and Plot

• Chapter Nineteen •: A Change in the Wind

• Chapter Twenty •: Surprises and a Journey

• Chapter Twenty-One •: A Quiet Journey Interrupted

• Chapter Twenty-Two •: Different Ideas and Hasty Decisions

• Chapter Twenty-Three •: An Awakening and Alarm

• Chapter Twenty-Four •: An Arrival and a Sudden Change of Plans

• Chapter Twenty-Five •: Upheaval and Changes

• Chapter Twenty-Six •: A Meeting and Revelations

• Chapter Twenty-Seven •: Fate Wheels and Lives Change

• Chapter Twenty-Eight •: Watching and Waiting

• Epilogue •: Return

Acknowledgements

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

• PROLOGUE •

A Murder of Crows and a King

Angry dark clouds hurried across the sky, foretelling more rain. A fair match for today’s mood, conceded Daylon Dumarch. The battle had ended swiftly as the betrayal had gone according to plan. The five great kingdoms of garn would never be the same; now the four great kingdoms, Daylon amended silently.

He looked around and saw carrion eaters on the wing: the vultures, kites, and sea eagles were circling and settling in for the feast. To the north, a massive murder of crows had descended on the field of corpses. Rising flocks of angry birds measured the slow progress of the baggage boys loading the dead. The carrion eaters were efficient, conceded Daylon; few bodies would go to the grave without missing eyes, lips, or other soft features.

He turned to gaze at the sea. No matter what the weather, it drew Daylon; he felt dwarfed by its eternal nature, its indifference to the tasks of men. The thought soothed him and gave him much-needed perspective after the battle. Daylon indulged in a barely audible sigh, then considered the beach below.

The rocks beneath the bluffs of the Answearie Hills had provided as rich a meal for the crabs and seabirds as the banquet for the crows and kites on the hills above them. Hundreds of men had met their death on those rocks, pushed over the edge of the cliff by the unexpected attack on their flank by men they had counted as allies but moments before.

Daylon Dumarch felt old. The Baron of Marquensas was still at the height of his power, not yet forty years from his nativity day, but he was ancient in bitterness and regret.

Thousands of men had died needlessly so that two madmen could betray a good king. While others stood by and did nothing, a balance that had existed for nearly two hundred years had been overturned. Art, music, poetry, dance, and theatre would soon follow the army of Ithrace into oblivion.

Daylon did not know exactly what plans the four surviving monarchs of the great kingdoms had for the lofty towers and flower-bedecked open plazas of the city of Ithra, but he feared for the most civilized city in the world, the capital of the Kingdom of Flames. Of the five great kingdoms of Garn, Ithrace had always produced the most artistic genius. Authors of Ithrace had penned half of the books in Daylon’s library, and Ithra was a well-known spawning ground for talented young painters, musicians, playwrights, poets, and actors, despite also providing refuge for thieves, mountebanks, whores, and every other form of unsavoury humanity imaginable.

There had always been five great kingdoms, and now that flame was ash only four remained – Sandura, Metros, Zindaros, and Ilcomen – and no man could anticipate how history would judge what had occurred this day. Daylon realised his mind was racing; he was barely able to focus on the moment, let alone the long-term political consequences of the horror surrounding him. It was as his father had said to him years ago; there are times when all one can do is stand still and breathe.

Daylon resisted letting out a long sigh of regret. Somewhere up the hill from where he stood, Steveren Langene, king of Ithrace, known to all as Firemane, lifelong friend to any man of good heart, ally of Daylon and a host of others, was being bound in iron shackles and cuffs by men he’d once called comrades, to be marched up onto the makeshift platform his brother kings had ordered constructed for this farce.

Daylon turned his mind from the coming horrors and his revulsion at his own part in today’s treachery and searched for somewhere to wash the battle from his face. He found a supply wagon overturned, its horses dead in their traces, but somehow a water barrel had conspired to remain mostly upright. Using his belt knife he cut away the waxed canvas cover and stuck his head into the cool, clean water. He drank, and came up sputtering, wiping the day’s blood and dirt from his face. He stood staring at the water as it rippled and calmed. It was the only thing Daylon could see that wasn’t covered in death; all around him, the mud of the battlefield was awash in piss, shit, and blood, pieces of what had once been brave men, and the muck covered banners of fools.

HIS LIFE HAD BEEN SCARRED by battle and death. Married twice before he was thirty five, Daylon had deeply loved his first wife, but she died in childbirth in their third year of marriage. He didn’t care much for his current wife, but she had brought a strong alliance and a fair dowry, and despite being vapid and silly, she had a strong young body he enjoyed and she was already expecting his first child. The promise of an heir was the one bright hope in his life at present.

He forced his attention from dark thoughts and saw a familiar figure approaching. ‘My lord,’ said Rodrigo Bavangine, Baron of the Copper Hills, ‘you have survived.’

‘The day is young,’ replied Daylon, ‘and there’s still treachery in abundance. Keep hope. You may yet be able to pay court to my young widow.’

‘A black jest,’ said Rodrigo. ‘Too many good companions lie befouled in their own entrails, while men I would not piss on were they afire celebrate this day.’

‘’Tis ever thus, Rodrigo.’ Daylon studied his old friend. The Baron of the Copper Hills was a dark-haired man with startling blue eyes. At court he wore his hair long, oiled and curled, but now had it gathered up in a bright red head cloth designed to keep it under his helm in battle. He was pale of complexion, like most people from the foggy and cloud-shrouded land he ruled. Daylon had always found it odd that they had become close, as Daylon was a man of deep consideration and Rodrigo seemed to barely consider the consequences of his impulses, but he knew Rodrigo’s moods as well as he knew his own. He saw the man’s face and knew without words they were of like mind. Both men wondered if the battle would have swung the other way had they stood with Steveren rather than opposed him.

Rodrigo narrowed his pale eyes and moved closer to speak quietly, though there was no living man within a dozen paces. ‘I can tell you this one thing, Daylon: from this day forward I shall never take to my bed without the benefit of a strong drink or a young arse, most likely both, and sleep a night without haunting. This business will bring more destruction, not less as was promised.’

Daylon leaned against the frame of the wagon watching the carpenters finishing up the executioner’s platform and turned to look at his old friend.

Rodrigo recognised his expression and manner. ‘You are a man of ideals, Daylon, so you need justification. Therein lies the cause of your distress.’

‘I am a far simpler man, Rodrigo. I merely picked the side I knew would win.’

‘And I followed you.’

‘As did others,’ said Daylon, ‘but I ordered no oathman, nor asked friend nor ally, to serve at my whim. Any could have said no.’

Rodrigo smiled, and it was a bitter look he gave to his friend. ‘Aye, Daylon, and that’s the evil genius of it. It’s a gift you have. No man in your orbit would oppose your counsel. You are too versed in the games of power for me not to heed your wisdom, even to serve foul cause.’

‘You could have opposed me and served Steveren.’

‘And find myself with them?’ he said, indicating the rotting dead in the mud.

‘There is always a choice.’

‘A fool’s choice,’ Rodrigo said softly, ‘or a dreamer’s.’ Pointing to the workers at the top of the hill, finishing up the platform, he changed the subject. ‘What is going on up there?’

‘Our victorious monarchs require some theatre,’ said Daylon sourly.

‘I thought Lodavico closed all the theatres in Sandura?’

‘He did. After complaining that the plays were all making a jest of him. Which was occasionally true, but he lacks perspective, and a sense of humour.’ Daylon added, ‘And he’s completely incapable of seeing the bitter irony in this.’

‘This theatre is entirely too macabre for my taste.’ Rodrigo passed his hand in an arc around the battlefield littered with dead. ‘Killing men in the heat of battle is one thing. Hanging criminals or beheading them is another. I can even watch heretics burn without blinking much, but this killing of women and children …’

‘Lodavico Sentarzi fears retribution. No Langene left alive means the King of Sandura can sleep at night.’ Daylon shrugged. ‘Or so he supposes.’ He kept his eyes fixed on the makeshift stage at the top of the hill. The workers had finished their hasty construction of the broad stage: two steps above the mud, elevated just enough for those on the hillside to be able to see, sturdy enough to support the weight of several men. Two burly servants wrestled a chopping block up the steps while a few of Lodavico’s personal guards moved between the makeshift construction and the slowly gathering crowd.

‘This business of bashing babies against walls, ugly that … and killing those pretty young daughters and nieces … that wasn’t merely a waste, it was an iniquity,’ complained Rodrigo. ‘Those Firemane girls were breathtaking, with those long necks and slender bodies, and all that red hair—’

‘You think too much with your cock, Rodrigo.’ Daylon tried to sound light-hearted. ‘You’ve had more women and boys than any ten men I know, and yet you hunger for more.’

‘To each man his own appetites,’ conceded Rodrigo. ‘Mine easily turn to a pretty mouth and rounded arse.’ He sighed. ‘It’s no worse than King Hector’s love of wine or Baron Haythan’s lust for gambling.’ He studied his friend for a moment. ‘What whets your appetite, Daylon? I’ve never understood.’

‘I seek only not to despise the man I see in the mirror,’ said the Baron of Marquensas.

‘That’s far too abstract for my understanding. What really fires you?’

‘Little, it seems,’ Daylon replied. ‘As a young man I thought of our higher purpose, for didn’t the priests of the One God tell our fathers that the Faith brings peace to all men?’

Rodrigo looked at the nearby battlefield littered with the dead and said, ‘In a sense, life eventually brings peace.’

‘That may be the most philosophical thing I’ve ever heard you say.’ Daylon’s gaze followed Rodrigo’s and he muttered, ‘The One God’s priests promised many things.’

Rodrigo let out a long, almost theatrical sigh, save Daylon knew his friend was not the sort to indulge in false play; the man was tired to his bones. ‘When four of the five great kings declare a faith the one true faith, and all others heresy, I expect you can promise most anything.’

Daylon’s brow furrowed a little. ‘Are you suggesting the Church had a hand in this?’

Rodrigo said, ‘I suggest nothing, old friend. To do so would be to invite ruin.’ His expression held a warning. ‘In our grandfathers’ time, the One God’s church was but one among many. In our fathers’ time, it became a force. Now …’ He shook his head slightly. ‘By the time of our children, the other gods will have withered to a faint memory.’ He glanced around as if ensuring they were not overheard. ‘Or, if their priests are clever enough, they might contort their doctrine to become heralds of the One God and survive as shadows of their former selves. Some are saying thus now.’ He paused for a moment, then said, ‘Truly, Daylon. What moves you in this? You could have stayed home.’

Daylon nodded. ‘And had my name put on a list with those who openly supported Steveren.’ He paused, then said, ‘Truth?’

‘Always,’ replied his friend.

‘My grandfather and my father built a rich barony, and I have taken what they’ve left me and made it even more successful. I wish to leave my children with all of it, but also have them secure in their holdings.’

‘You are close to a king yourself, aren’t you?’

Daylon shared a rueful smile with his friend. ‘I’d rather have wealth and security for my children than any title.’

Satisfied no one was within earshot, Rodrigo let his hand come to rest on Daylon’s shoulder a moment. ‘Come. We should attend. This is not a good time to be counted among the missing, unless you happen to be dead already, which their majesties and Mazika might count a reasonable excuse. Anything else, not.’

Daylon inclined his head slightly in agreement and the two noblemen trudged the short walk up the muddy hillside as the rain resumed. ‘Next time you call me to battle, Daylon,’ said Rodrigo, ‘have the decency to do so on a dry morning, preferably in late spring or early summer so it’s not too hot. I have mud in my boots, rain down my tunic, rust on my armour, and my balls are growing moss. I haven’t seen a dry tunic in a week.’

Daylon made no comment as they reached the top of the hill where the execution was to be held. Common soldiers glanced over their shoulders and, seeing two nobles, gave way to let them pass until Rodrigo and Daylon stood in the forefront of the gathering men. The platform was finished and the prisoners were being marched out of the makeshift pens where they’d been kept overnight.

Steveren Langene, King of Ithrace, had been fed false reports and lies for a year, until he thought he was joining with allies to meet aggression from King Lodavico. Daylon was one of the last barons to be told of the plan, which had given him little time to consider his options. He and Rodrigo had less than a month to ready their forces and march to the appointed meeting place; most importantly, they were given no opportunity to warn Steveren and aid him effectively. Distance and travel time prevented Daylon or others sympathetic to the king of Ithrace from organizing on Steveren’s behalf. Even a message warning him might be discovered by Lodavico and earn Daylon a place on the executioner’s stage next to Steveren.

This morning, they had arisen to fix their order of battle, trumpets blowing and drums pounding, Steveren’s forces holding the leftmost position, awaiting Lodavico’s attack. The battle order had been given and suddenly King Steveren’s allies had turned on him. It had still been a bitter struggle and most of the day was gone, but in the end, betrayal had triumphed.

Daylon could see the prisoners being forced out of the pens on the other side of the platform. While Steveren’s army had been in the field, slogging through the mud of an unseasonably heavy summer storm, raiders had seized the entire royal family of Ithrace from their summer villa on the coast less than half a day’s ride away.

Cousins of blood and kin by marriage had already been put to the sword, or thrown off the cliffs onto the rocks below the villa – by all accounts more than forty men, women, and children. Even the babies were not spared. But the king’s immediate family had been granted an extra day’s existence to suffer this public humiliation. Kings Lodavico and Mazika were determined to show the world the end of the Firemane line.

Now that royalty was being marched at spear-point to their deaths.

The children came first, terror and bewilderment rendering them silent. They shuffled along with eyes wide, lips blue from the cold and limbs trembling, their red hair rendered a dull dark copper by the rain. Daylon counted the little ones, two boys and a girl. Their older siblings came after, followed by Queen Agana. Last was King Steveren. Whatever finery they had worn had been torn off, and they were all dressed in the poorest of robes, their exposed limbs and faces showing the bruises of the beatings they had endured.

King Steveren wore a yoke of hardwood, with iron cuffs at each end confining his wrists, and his legs were shackled so he shambled rather than walked. He was prodded up the steps to the platform while the army gathered. From the swelling bruises on his face and around his eyes, it was miraculous that he could walk without aid. Daylon saw the dried blood on his mouth and chin, and winced as he realised the king’s tongue had been cut so he could not speak to those gathered to watch him die.

A few soldiers shouted half-hearted jeers, but every man standing was tired, some wounded, and all wished for this to be over quickly so they might eat and rest. For most, the approaching sack of Ithra was why they had served today, and that would not begin until this matter was put paid to, so all wished for a hastened ending.

Daylon glanced at Rodrigo, who shook his head ever so slightly in resignation. There was no precedent for this butchery, and no one could reconcile what they were about to see with what they understood of the traditional order of things. History taught that a king did not kill a king, save on the field of battle; even barons were rarely executed, but usually ransomed for profit and turned to vassals.

For as long as living memory on the world of Garn, five great kingdoms had dominated the twin continents of North and South Tembria. Scattered among them were independent states ruled by the most powerful barons, men like Daylon and Rodrigo, free nobles allied with, but not subject to, those kings. Other, lesser nobility held grants of land and titles from the five great kingdoms.

Daylon locked eyes with Rodrigo, and in that instant knew that his friend understood as well as he that an era was ending. What had been a long period of prosperity and relative peace was over.

For two centuries, the five great kingdoms of North and South Tembria had been bound by the Covenant: the solution to centuries of warfare over control of the Narrows, the sea passage between the two continents. It was the choke-point at which two outcrops of land had created a passage so constricted that no more than half a dozen ships – three eastbound and three westbound – could navigate and pass safely at the same time. The need to reduce speed here and the overlooking rocks had made this the most prized location on Garn, for whoever controlled the straits controlled all east–west shipping across two continents; the alternative sea routes around the north or south of the twin continents were so difficult and time-consuming that they were considered to be close to impossible. Alternative land transport would take triple the time, and twice the cost.

The Covenant guaranteed right of passage for all. A circular boundary of Covenant lands had been drawn around the Narrows on both continents. No city could be built there, only small towns and villages were permitted to flourish, and all rulers guaranteed its neutrality. This mutual ceding of land by the five great kingdoms had created peace and fostered trade, the arts, and prosperity.

Until today, thought Daylon bitterly. The survivors of this madness might continue the fiction that the Covenant still existed, but Daylon knew it was over. The pact might appear to die slowly, but in reality it was already dead.

He studied the faces of the Ithraci royal family, the terror in the eyes of the children, the resignation and hopelessness in the faces of the women, and the defiance of their king. Steveren Langene, called Firemane for the bright red hair that was his line’s hallmark, was forced to his knees with a kick to the back of his legs as two soldiers pushed down hard on his wooden yoke.