Полная версия:

The Making of Her: Why School Matters

THE MAKING OF HER

Why School Matters

Clarissa Farr

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.williamcollinsbooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright © Clarissa Farr 2019

Cover photograph © Shutterstock

Clarissa Farr asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Image here from Christopher Alexander, Murray Silverstein, Sara Ishikawa, A Pattern Language Towns, Buildings, Construction (Oxford University Press, 1977)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008271305

Ebook Edition © August 2019 ISBN: 9780008271312

Version: 2019-08-07

Dedication

Remembering my parents, Alan and Wendy Farr

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Foreword

Chapter 1 September: Back to school – ‘the make-believe of a beginning’

Chapter 2 October: A question of gender – still vindicating the rights of women?

Chapter 3 November: Headship – opening up the path on which the next generation will travel

Chapter 4 December: Living in community – the love of tradition and the role of co-curricular life

Chapter 5 January: Competition and cooperation – what kind of education do we want for our children?

Chapter 6 February: Be a teacher – be the one you are

Chapter 7 March: Promoting well-being and mental health – a twenty-first-century challenge

Chapter 8 April: When things go wrong – running with risk, facing up to failure, living with loss

Chapter 9 May: Creating the triangle of trust – working with today’s parents

Chapter 10 June: Valediction and looking to the future

Afterword

Notes

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

Foreword

Coming back from teaching to my office, I find an intricate, pop-up paper sculpture made from the insides of a book perching like a curious bird on my desk, with a note from the artist. Meanwhile, a shock netball match result against a team we were certain to beat reverberates around the building. A tutor reports that a head of peacock-blue hair has materialised in the Lower V (surely it was brown yesterday?) and we discuss whether this requires a response. On results day, a girl is face down on the marble concourse after it emerges she has a near-disastrous GCSE profile of nine A*s and one A. Four of our youngest girls come to see me to ask if I can be filmed saying the first word that comes into my head when they say ‘Paulina’ (‘independent’). And just after Christmas, my urgent attention is required by parents whose daughter has been offered a place at the wrong Oxbridge college. What, Ms Farr, are you going to do about it?

Such are the fragments that make up the life of a headmistress – but how to capture them? The headlong nature of schools means I could do little more than fire off the occasional letter to The Times from my iPhone while heading towards the Great Hall of St Paul’s to take assembly, scribbled notes flying. And even if I could set them down, would anyone be interested?

School. The word conjures a world at once so familiar as to be hardly worthy of comment (much less a book) but at the same time often attended with emotion: for some, affection and nostalgia, for a few, sadly, hostility and anger. There are those for whom school was a mixed or even traumatic experience, those for whom it was mainly rather dull and, equally, there are some for whom nothing has ever been quite as much fun since.

This book is for anyone who has been to school. I invite you to go back in time to that unique and personal world, to walk the academic year with me and to reconnect in memory with the teachers, places and habits that were yours. This isn’t meant as therapy, you understand: how would I presume to offer that? I have been lucky: happy for the most part at school in Somerset (I’ve expunged the memory of diving into the freezing outdoor pool in April) and apart from the equally icy coldness of the billowing, black-clad nuns at my convent primary school, my school days were far from traumatic. But whatever our recollection of school, to revisit that impressionable time is to understand better who we have become and why. And the more we can turn our education to good account in the present, the more we can help our children, whose adult lives will be so different from ours, to do the same.

School came to mean something different when I became a teacher – not through a high-minded desire to serve the next generation but because, while putting the finishing touches to my MA dissertation, I was, somewhat pretentiously, obsessed by the novels of Henry James. ‘Live! … Live all you can; it’s a mistake not to,’ he writes in The Ambassadors – and I wanted to do so. This meant finding an excuse to go on reading James while being paid and, if possible, persuading my students of the unrivalled brilliance of these works. In practice as a teacher I rarely touched on his labyrinthine novels – most of my pupils would have been escaping through the doors (or windows) before I reached the end of the first, attenuated, periodic, excruciatingly Jamesian sentence. Instead, I was surprised to find I liked the company of my students for its own sake: their quick-wittedness, their irreverence, their refusal to be impressed.

I began my working life in the ordered world of Farnborough Sixth-Form College. The students were barely younger than I was and teaching Chaucer’s Miller’s Tale as a twenty-two-year-old young woman to a class peppered with eighteen-year-old boys provided challenges I hadn’t been trained for (no, they might not kiss me – not even once – at the end of term). I was able to learn some of the craft of teaching with A-level students who had chosen their subjects and were eager to learn. This was not a given in all classrooms, as I found out later when I moved from this ambrosial world to the spin-dryer that was Filton High School in Bristol, a city comprehensive. There it was period eight, last of the day, with a bottom-set class of adolescents, that everyone dreaded, but I learned there everything I know about classroom control and how to discipline a rowdy room through timing and silence.

Three years in the Far East followed as I finally shed my West Country tethers, arriving at Sha Tin College in glittering, clattering Hong Kong. When the prospect of becoming a gin-and-tonic-swilling expat palled, I returned to the gloomier skies of England’s heart and Leicester Grammar School, where at the time, Richard III was still safely buried under a city centre car park. There I began my life in senior management, with the monitoring of skirt lengths, the removal of nail varnish and timetabling in my wide-ranging portfolio. I moved into girls’ education (much easier for an ambitious woman wanting to get to the top than staying with co-education, at that time) as deputy head at my mother’s old school, Queenswood in Hertfordshire, in 1992. When the headmistress, Audrey Butler, retired four years later, I was chosen to succeed her. My father, rarely a man to waste words on optimistic sentiment, beamed with pride: his girl was obviously as bossy as he was – what joy! Ten years followed, during which I also married and had two children, before the chance of running the schools’ equivalent of Manchester United came up. Elizabeth Diggory was to retire from St Paul’s. The stars were aligned, the timing was perfect and I came to lead my first and only London day school in September 2006.

Drawing upon my own experiences as a pupil, teacher, headmistress and mother, I have in mind as I write those who are parents of teenagers, particularly those bringing up girls. After twenty-five years in girls’ education, I have well-founded respect and admiration for the young women of this age group (though a few of them have almost driven me nuts) – with their optimism, their intelligence, their determination and their wonderful sense of humour. Whether or not the ‘girls’ school movement’, as it was once grandly called, survives – and that must be a question, despite the growing body of research defending the need for girls to be educated separately – there has to be continued attention paid to the education of girls, if the special talents and gifts they offer are to be brought out for the world’s greater benefit.

As a leader in education, seeing many common preoccupations across the sectors, I am also writing for anyone responsible for the work of others, where the task is to encourage a group of people to cohere behind a shared vision. Schools are exceptionally complex, with so many constituencies to read and keep happy: governors, staff, parents and students past, present and future, the general public, the government, the inspectorate and, for most independent schools while they remain charities, the Charity Commission. But the central elements of effective leadership are readily recognisable and transferable, so I offer observations from my own experience, including my mistakes, for the parallels others may smilingly draw with their own.

Finally, this book is for any person who wants simply to reflect on their own life, their opportunities and choices, and the unique path we each follow as we gradually make and remake ourselves: the inexorable process of becoming the person we are destined to be.

CHAPTER 1

September

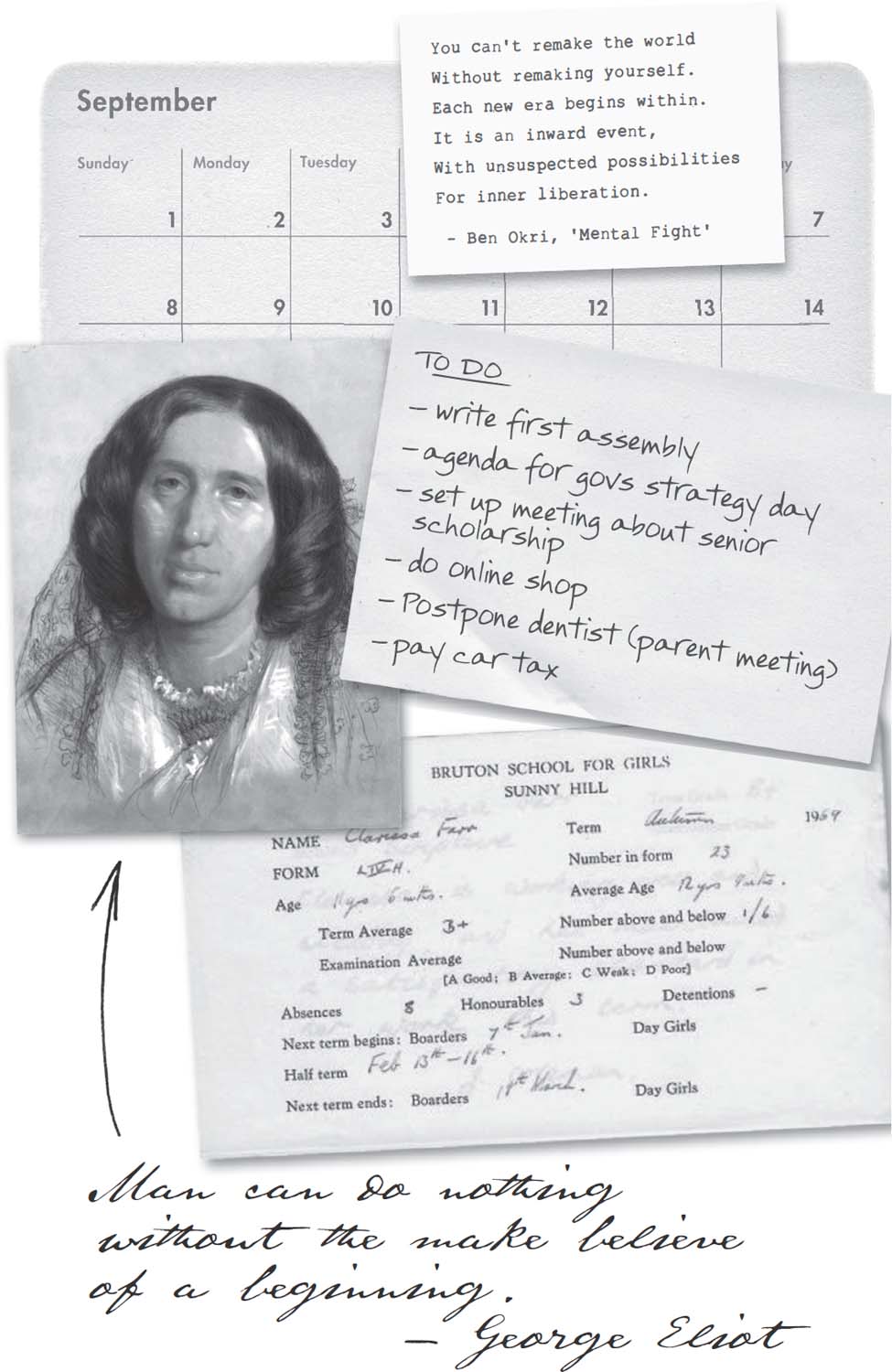

Back to school – ‘the make-believe of a beginning’

The bank holiday weekend is over, summer is waning and as the season turns, the soft, slanting afternoon light reminds us it’s time to be getting ready for the new term. For some weeks, vast electronic billboards looming over city roads have borne the cheerful exhortation ‘Back to School!’ The angelic, tousle-headed children, pictured wearing their Teflon-coated school trousers with improbably white shirts and artfully skewed ties, seem to think that none of us can wait for the holidays to be over. Real children, alert for any shopping opportunity, badger their parents for new stationery, with its cellophane-wrapped, freshly minted smell and brightly coloured promise: pristine pads of hole-punched paper, rainbow post-it notes, neat geometry sets, rulers, rubbers and writing equipment in every shape and colour. For them, the time soon comes to pack your bag, board the school bus, find your locker in the cloakroom and print your name neatly on a fresh exercise book. For parents, after the flurry of gathering everything, once the term starts, a little silence falls. And for the teachers and the head, the task is to get the whole glittering enterprise launched once again. As a new academic year begins, everyone has their own hopes and aspirations and perhaps some anxieties too: this is when the foundations are laid for the school life that unfolds, month by month, and which I will sketch through the pages of this book.

A book, a chapter, a school life: what does it mean to start something – and is a beginning ever truly that? ‘Men can do nothing without the make-believe of a beginning,’ writes George Eliot, as the opening words of Daniel Deronda. Something in us needs that sense of starting afresh to give us purpose. We want to separate what has gone before from what is to come, to shape and construct the future. Perhaps it reflects our fundamental optimism – and nowhere is that felt more powerfully than in a school, where young people are looking to their future and all the possibilities it holds. With their ingrained temporal structure of a year divided into three terms, terms divided into weeks, weeks into the daily timetable, and each day into its lesson compartments, schools provide regular opportunities for that act of renewal. At the same time the annual starting point is odd: why September? If like me you have spent your life in education, you are hard-wired to see the month that ushers in autumn, two-thirds of the way through the calendar year, as its beginning. Children are no longer employed in the fields during the summer months gathering in the harvest, yet the academic year still starts here. The long annual summer holiday in July seems at first a release from the remorselessness of the school year. But all too soon for children set free, the axis turns and the new term looms. Even now after so many years I feel a certain habitual apprehension at this time – will all go well with those first few days? Going back to school is a bit like getting out for that morning run: the thought of it is the worst bit – once you’ve done it you remember how you enjoy it and, each year, there is a moment to begin again. Japanese children return to school in April, when the spring cherry blossom offers the most natural sign of new beginnings. Different traditions but the same effect: a page turned and a fresh start.

The first day arrives and the school buildings that have been eerily quiet – only the noise of a distant drill from some maintenance work breaking the silence – are suddenly filling with voices. Younger children make their way through the school gates carrying their too-new rucksacks, eyeing the older ones who, oblivious, are nonchalantly removing earbuds. Parents, dismissed, wave goodbye and hesitate, feeling a mixture of anxiety and relief. Inside, teachers are already in their classrooms, noticeboards cleared, preparing for the arrival of their classes. As a young teacher, I would print up my long blue mark book with the names of the pupils in each of my classes on the left-hand side, the double spread of squared cream paper ready to receive the recorded marks that would build up like a secret code of letters and herringbone strokes across the page as the year wore on. A whole blueprint was contained in those thick, pristine pages: the yet-to-be-written history of your world, of your life as a teacher, and of the progress of pupils in your care.

What are your recollections of going back to school? It’s a question that often prompts strong reactions. Whether or not we enjoyed them at the time, our school days are formative: whatever our path in life, especially if we are parents contemplating the schooling of our own children or if we become professional teachers, our own experience of being a pupil is never far below the surface, inevitably colouring our views. However long ago it was, we have a reservoir of stored memories of our early lives and our time at school which can shed light on how we have developed into our adult selves. You might be surprised to find just how fresh those early memories are, once you invite them to the surface. Affection and a certain nostalgia may sweeten the picture, but all those injustices or near misses come straight back too. Sadly, some are seriously scarred by the memories, and it’s a pity that we hear so many more of those stories than the happier ones. Whatever it was like, it’s now a part of you.

Given how much we read about people who were miserable at school, I feel lucky that for me it was for the most part a happy experience. This has been continually influential in my work because I know, from first-hand experience, that there are few things so grounding and reassuring to a child as feeling you truly belong to your school community. When school takes on that unforced comfortable familiarity, the buildings themselves, the favourite corners where you linger with your friends, the routes and corridors you traverse at full tilt (unless a teacher is coming), your lessons, the teachers themselves, your friends, the soundscape of bells and clatter, the smell of the polish even: these things make up your entire world. There is no sense of being in some anteroom, peering in from the sidelines of an adult world waiting for real life to begin. This is it and you are the centre of it. When pupils feel at home at school in this way, they are at their most naturally confident and this is when the best learning is done. As a head, I simply wanted every child to know that feeling; so creating the conditions for it informed everything.

Of course, there are always some children who find it more difficult to integrate, even though often they may very much want to belong. In a high-achieving intellectual environment (where you test for many things but not emotional intelligence) there are more pupils than you might think who, despite their prodigious gifts, find the social contact with others difficult. And there are always a few who stubbornly resist, at odds with their school, rejecting its values and authority. They will not allow their individuality to be diluted, to be lured into some institutional conformity and suffer agency capture! They would be the grit in the oyster. But over time, a little pearl would often secrete itself around these too. For on the whole, especially when joining a new school at age eleven, children don’t want to be different or to stand out; they want to be accepted, and the first few weeks are all about fitting in and becoming part of the tribe. Pupils learn to belong by watching, adapting and through myriad small adjustments that often go under adult radar. Their ‘pack’ is their form, or tutor group, and this is the unit in which they first find their feet.

The importance of helping new pupils feel secure and grounded in their year group was a priority for me as a head because of something that happened to me, no doubt from the best of intentions, when at school in my first senior school year.

I had joined my senior school, Sunny Hill (known more formally as Bruton School for Girls), set on a rolling green hilltop outside Bruton, Somerset, in 1968. Aged ten, I was placed in Miss Reed’s first-form class. The youngest children in the school, we were taught in a long wooden hut with a gabled roof and its own small garden, rickety windows and walls pockmarked by drawing pins where our pictures, stories and poems were proudly displayed. Miss Reed, a tiny person with the bright brown eyes of a mouse, had the appearance of someone who spent her weekends taking bracing walks along cliff paths. That first term I quickly made friends and felt both absorbed and stimulated by everything we did; it was one of the happiest of my school days. But then everything changed.

One morning at the start of the second term, Miss Reed called me up to her desk. ‘I’ve something to tell you, Clarissa,’ she said, eyes twinkling. ‘You’re being moved up a year. The work will be more stretching. And it’s also that you’re more mature than the others …’ Mature! What was that? My world had just fallen apart. When was I to start? Well, there was no time like the present: it would be at once. Miserably, I said goodbye to my friends and was escorted down unfamiliar corridors to the alien, too-bright world of my new form room, where at the desk next to mine a sturdy girl with a pale-brown fringe and sensible glasses called Margaret Morgan had been told to look after me. Margaret was politely kind, but after a few days she admitted one break-time how she was missing spending time with her best friend, Cecily Krasker, and gratefully went off to find her. Sitting alone on a wall, I hoped I didn’t look too conspicuous and longed for the bell to ring so that I could return to the anonymity of the class.

Untethered from the lovely security of Miss Reed’s class and my friends, I was lost. I dreaded the long lunch hours where I would drift around, trying to attach myself to one group of girls or another. They were kind enough, but nobody really wanted me: friendships had formed a year ago and this new, younger girl was an awkward thing. I felt childish next to these impossibly mature thirteen-year-olds who had started to wear bras and have periods. Once only interested in the fascinating world of discovery that was the first-form classroom, now I was ashamed of my failure to reach these very different milestones. At last, after much hinting, my mother did allow me to have a bra and there was a mortifying trip to the local outfitters, where she and the well-padded assistant exchanged amused glances as an infinitesimally small garment was selected. We bought two, neatly packed in cardboard boxes, like clothing for a doll. One on, one in the wash, the assistant said efficiently. The anxiously awaited arrival of my periods – a rite of passage in the lives of all young girls – came to me long after it had ceased to be a newsworthy matter to our class generally, accompanied by a silent relief that, alone in the bathroom at home, I shared with no one.

Children adapt and are often more resilient than we expect. I eventually settled in to the new class and by the following year, had made friends and was starting to enjoy academic work again. From that unnecessarily rocky start I went on to have six more happy years at the school. In my penultimate year, unlooked-for success was secured as a result of a chance meeting between my grandmother and the headmistress in a local tea shop. Miss Cumberlege (I will come back to her later), seeking no doubt to make polite conversation, said to my grandmother: ‘Clarissa seems to be doing very well at school …’ to which my grandmother replied magnificently: ‘Doing well? Clarissa could run an Empire!’ No doubt on the strength of this I was soon appointed one of the four head girls. So all ended well, but that early experience of being moved up always seemed a pointless emotional setback, never more so than when I emerged at the other end of the school having taken my A levels at barely seventeen, too young to go to university. I spent an unremarkable gap year working in our local pub and interrailing around Europe. Perhaps I was just doing a bit more growing up: it felt as if I’d been forced through things too quickly.

Whoever we are, our experience of school informs our values and our adult view of the world. Having been very young in the year, I’m now particularly alive to that predicament in school children and how it affects them in ways that may go undetected by the adult radar. Children live their school lives amongst their peers and experience much that the adults around them, however well intentioned, will never know (one reason why bullying and unkindness can be so hard to detect). Age matters hugely in early adolescence: however intellectually advanced a pupil is, if her (or his) emotional and physical development are not aligned with that of peers, especially around puberty, then being fast-tracked through the system may well do more harm than good. Parents can be impatient for their children to achieve academic milestones, but to what end? Of course they need to be stimulated but this can happen in so many lateral ways; they also need time to grow and be themselves, to develop at their own pace amongst friends and peers with whom they feel at home. This is what creates confidence and provides the secure foundation for their self-esteem throughout life.