Полная версия:

In the Darkroom

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

First published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2016

This eBook edition published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017

Copyright © 2016, 2017 by Susan Faludi

Susan Faludi asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This is a work of nonfiction. The names and identifying characteristics of three individuals have been changed to protect their privacy.

‘I Am Easily Assimilated’ from Candide by Leonard Bernstein. Lyrics by Leonard Bernstein. Copyright © 1994 by Amberson Holdings LLC. Copyright renewed, Leonard Bernstein Music Publishing Company, publisher. International copyright secured. Reprinted by permission.

Excerpt from ‘Red Riding Hood’ from Transformations by Anne Sexton. Copyright © 1971 by Anne Sexton, renewed 1999 by Linda G. Sexton. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Excerpt from ‘Optimistic Voices (You’re Out of the Woods)’ from The Wizard of Oz. Lyrics by E. Y. Harburg. Music by Harold Arlen and Herbert Strothart. Copyright © 1938 by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Inc., renewed 1939 by EMI Feist Catalog Inc. Rights throughout the world controlled by EMI Feist Catalog Inc. (publishing) and Alfred Music (print). Used by permission of Alfred Music. All rights reserved.

All photographs courtesy of the author, except for the following: here, Einar Wegener/Lili Elbe by Wellcome Library, London; here, Christine Jorgensen by Art Edger/NY Daily News Archive/Getty Images; here, Melanie’s Cocoon by Mel Myers; here, Class of ’45 photograph courtesy of Otto and Margaret Szekely; here, Parasite Press photograph courtesy of Judit Mészáros, the original in Budapest Collection of Szabó Ervin Central Library; here, Ford convertible by Marilyn Faludi; here, Magyar Garda rally by European Pressphoto Agency/Tamas Kovacs

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008194475

Ebook Edition © July 2017 ISBN: 9780008193515

Version: 2017-06-24

Additional Praise for In the Darkroom:

A SUNDAY TIMES BOOK OF THE YEAR 2016

‘Faludi’s remarkable, moving and courageous book is extremely fair-minded’

Guardian

‘In the Darkroom reads like a mystery thriller yet packs the emotional punch of a carefully crafted memoir. Susan Faludi’s investigation into her father’s life reveals, with humour and poignancy, the central paradox of being someone’s child. However close, our parents will always be, perhaps by nature of the role, fundamentally enigmatic to us’

AMANDA FOREMAN

‘Faludi weaves together these strands of her father’s identity – Jewishness, nationality, gender – with energy, wit and nuance … Faludi has paid her late father a fine tribute by bringing her to life in such a compelling, truthful story’

New Statesman

‘[A] mighty new book … a searching investigation of identity barely disguised as a sometimes funny and sometimes very painful family saga … reticent, elegant and extremely clever’

Observer

‘A fascinating chronicle of a decade trying to understand a parent who had always been inscrutable’

Economist

‘Compelling’

Sunday Times

Well-written … touching … compelling’

The Times

‘An astonishing, unique book that should be essential reading for anyone wanting to explore transsexuality’s place in contemporary culture’

Irish Independent

‘In the Darkroom is a unique, deeply affecting and beautifully written book, full of warmth, intelligence and humour’

Saturday Paper

Dedication

For the Grünbergers of Spišské Podhradie and the Friedmans of Košice, and their children and their children’s children, the family I found, and who found me

Epigraph

He thought about how he had been despised and scorned, and he heard everybody saying now that he was the most beautiful of all the beautiful birds. And the lilacs bowed their branches toward him, right down into the water. The sun shone so warm and so bright. Then he ruffled his feathers, raised his slender neck, and rejoiced from the depths of his heart. “I never dreamed of such happiness when I was an ugly duckling!”

Hans Christian Andersen, “The Ugly Duckling”

The identifying of ourselves with the visual image of ourselves has become an instinct; the habit is already old. The picture of me, the me that is seen, is me.

D. H. Lawrence, “Art and Morality”

Long ago

there was a strange deception:

a wolf dressed in frills,

a kind of transvestite.

But I get ahead of my story.

Anne Sexton, “Red Riding Hood”

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Additional Praise for In the Darkroom

Dedication

Epigraph

Preface: In Pursuit

PART I

1. Returns and Departures

2. Rear Window

3. The Original from the Copy

4. Home Insecurity

5. The Person You Were Meant to Be

6. It’s Not Me Anymore

7. His Body into Pieces. Hers.

8. On the Altar of the Homeland

9. Ráday 9

PART II

10. Something More and Something Other

11. A Lady Is a Lady Whatever the Case May Be

12. The Mind Is a Black Box

13. Learn to Forget

14. Some Kind of Psychic Disturbance

15. The Grand Hotel Royal

16. Smitten in the Hinder Parts

17. The Subtle Poison of Adjustment

18. You’re Out of the Woods

19. The Transformation of the Patient Is Without a Doubt

PART III

20. Pity, O God, the Hungarian

21. All the Female Steps

22. Paid Up

23. Getting Away with It

24. The Pregnancy of the World

25. Escape

Footnotes

About the Author

Also by Susan Faludi

About the Publisher

PREFACE

In Pursuit

In the summer of 2004 I set out to investigate someone I scarcely knew, my father. The project began with a grievance, the grievance of a daughter whose parent had absconded from her life. I was in pursuit of a scofflaw, an artful dodger who had skipped out on so many things—obligation, affection, culpability, contrition. I was preparing an indictment, amassing discovery for a trial. But somewhere along the line, the prosecutor became a witness.

What I was witness to would remain elusive. In the course of a lifetime, my father had pulled off so many reinventions, laid claim to so many identities. “I’m a Hungaaaarian,” my father boasted, in the accent that survived all the shape shifts. “I know how to faaaake things.” If only it were that simple.

“Write my story,” my father asked me in 2004—or rather, dared me. The intent of the invitation was murky. “It could be like Hans Christian Andersen,” my father said to me once, later, of our biographical undertaking. “When Andersen wrote a fairy tale, everything he put in it was real, but he surrounded it with fantasy.” Not my style. Nevertheless, I took up the dare with a vengeance, and with my own purposes in mind.

Despite the overture, my father remained a refractory subject. Most of the time our collaboration resembled a game of cat and mouse, a game the mouse generally won. My father, like that other Hungarian, Houdini, was a master of the breakout. For my part, I kept up the chase. I had cast myself as a posse of one, tracking my father’s many selves to their secret recesses. I was intent on writing a book about my father. It wasn’t until the summer of 2015, after I’d worked my way through many drafts and submitted the manuscript, and after my father had died, that I realized how much I’d also been writing it for my father, who, in my mind at least, had become my primary, imagined, and intended reader—with all the generosity and hostility that implies. It wasn’t an uncomplicated gift.

“There are things in here that will be hard for you to take,” I warned in the fall of 2014, when I called to announce that I had a completed draft. I braced myself for the response. My father, who had made a career in commercial photography out of altering images and devoted a lifetime to self-alteration, would hate, I assumed, being depicted warts and all.

“Waaall,” I heard after a silence. “I’m glad. You know more about my life than I do.” For once my father seemed pleased to be captured, if only on the page.

PART I

1

Returns and Departures

One afternoon I was working in my study at home in Portland, Oregon, boxing up notes from a previous writing endeavor, a book about masculinity. On the wall in front of me hung a framed black-and-white photograph I’d recently purchased, of an ex-GI named Malcolm Hartwell. The photo had been part of an exhibit on the theme “What Is It to Be a Man?” The subjects were invited to compose visual answers and write an accompanying statement. Hartwell, a burly man in construction boots and sweat pants, had stretched out in front of his Dodge Aspen in a cheesecake pose, a gloved hand on a bulky hip, his legs crossed, one ankle over the other. His handwritten caption, appended with charming misspellings intact, read, “Men can’t get in touch with there feminity.” I took a break from the boxes to check my e-mail, and found a new message:

To: Susan C. Faludi

Date: 7/7/2004

Subject: Changes.

The e-mail was from my father.

“Dear Susan,” it began, “I’ve got some interesting news for you. I have decided that I have had enough of impersonating a macho aggressive man that I have never been inside.”

The announcement wasn’t entirely a surprise; I wasn’t the only person my father had contacted with news of a rebirth. Another family member, who hadn’t seen my father in years, had recently gotten a call filled with ramblings about a hospital stay, a visit to Thailand. The call was preceded by an out-of-the-blue e-mail with an attachment, a photograph of my father framed in the fork of a tree, wearing a pale blue short-sleeved shirt that looked more like a blouse. It had a discreet flounce at the neckline. The photo was captioned “Stefánie.” My father’s follow-up phone message was succinct: “Stefánie is real now.”

The e-mail notifying me was similarly terse. One thing hadn’t changed: my photographer father still preferred the image to the written word. Attached to the message was a series of snapshots.

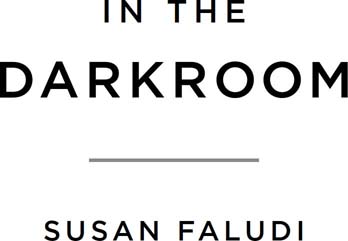

In the first, my father is standing in a hospital lobby in a sheer sleeveless blouse and red skirt, beside (as her annotation put it) “the other post-op girls,” two patients who were also making what she called “The Change.” A uniformed Thai nurse holds my father’s elbow. The caption read, “I look tired after the surgery.” The other shots were taken before the “op.” In one, my father is perched amid a copse of trees, modeling a henna wig with bangs and that same pale blue blouse with the ruffled neckline. The caption read, “Stefánie in Vienna garden.” It is the garden of the imperial villa of an Austro-Hungarian empress. My father was long a fan of Mitteleuropean royals, in particular Empress Elisabeth—or “Sisi”—Emperor Franz Josef’s wife, who was known as the “guardian angel of Hungary.” In a third image, my father wears a platinum blond wig—shoulder length with a ’50s flip—a white ruffled blouse, another red skirt with a pattern of white lilies, and white heeled sandals that display polished toenails. In the final shot, titled “On hike in Austria,” my father stands before her VW camper in mountaineering boots, denim skirt, and a pageboy wig, a polka-dotted scarf arranged at the neck. The pose: a hand on a jutted hip, panty-hosed legs crossed, one ankle before the other. I looked up at the photo on my wall. “Men can’t get in touch with there feminity.”

The e-mail was signed, “Love from your parent, Stefánie.” It was the first communication I’d received from my “parent” in years.

My father and I had barely spoken in a quarter century. As a child I had resented and, later, feared him, and when I was a teenager he had left the family—or rather been forced to leave, by my mother and by the police, after a season of escalating violence. Despite our long alienation, I thought I understood enough of my father’s character to have had some inkling of an inclination this profound. I had none.

As a child, when we had lived together in a “Colonial” tract house in the suburban town of Yorktown Heights, an hour’s drive north of Manhattan, I’d always known my father to assert the male prerogative. He had seemed invested—insistently, inflexibly, and, in the last year of our family life, bloodily—in being the household despot. We ate what he wanted to eat, traveled where he wanted to go, wore what he wanted us to wear. Domestic decisions, large and small, had first to meet his approval. One evening, when my mother proposed taking a part-time job at the local newspaper, he’d made his phallocratic views especially clear: he’d swept the dinner dishes to the floor. “No!” he shouted, slamming his fists on the table. “No job!” For as far back as I could remember, he had presided as imperious patriarch, overbearing and autocratic, even as he remained a cipher, cryptic to everyone around him.

I also knew him as the rugged outdoorsman, despite his slender build: mountaineer, rock climber, ice climber, sailor, horseback rider, long-distance cyclist. With the costumes to match: Alpenstock, Bavarian hiking knickers, Alpine balaclava, climber’s harness, yachter’s cap, English riding chaps. In so many of these pursuits, I was his accompanist, an increasingly begrudging one as I approached adolescence—second mate to his captain on the Klepper sailboat he built from a kit, belaying partner on his weekend assays of the Shawangunk cliffs, second cyclist on his cross-the-Alps biking tours, tent-pitching assistant on his Adirondack bivouacs.

All of which required vast numbers of hours of training, traveling, sharing close quarters. Yet my memory of these ventures is nearly a blank. What did we talk about on the long winter evenings, once the tent was raised, the firewood collected, the tinned provisions pried open with the Swiss Army knife my father always carried in his pocket? Was I suppressing all those father-daughter tête-à-têtes, or did they just not happen? Year after year, from Lake Mohonk to Lake Lugano, from the Appalachians to Zermatt, we tacked and backpacked, rappelled and pedaled. Yet in all that time I can’t say he ever showed himself to me. He seemed to be permanently undercover, behind a wall of his own construction, watching from behind that one-way mirror in his head. It was not, at least to a teenager craving privacy, a friendly surveillance. I sometimes regarded him as a spy, intent on blending into our domestic circle, prepared to do whatever it took to evade detection. For all of his aggressive domination, he remained somehow invisible. “It’s like he never lived here,” my mother said to me on the day after the night he left our house for good, twenty years into their marriage.

When I was fourteen, two years before my parents’ separation, I joined the junior varsity track team. Girls’ sports in 1973 was a faintly ridiculous notion, and the high school track coach, who was first and foremost the coach of the boys’ team, mostly ignored his distaff charges. I designed my own training regimen, leaving the house before dawn and loping the side streets to Mohansic State Park, a manicured recreation area that used to be the grounds for a state insane asylum, where I ran a long circuit around the landscaped terrain, alone. By then, I had developed a preference for solo sports.

Early one August morning I was lacing my sneakers in the front hall when I sensed a subtle atmospheric change, like the drop in barometric pressure as a cold front approaches or the prodromal thrumming before a migraine, which signaled to my aggrieved adolescent mind the arrival of my father. I reluctantly turned and made out his pale, thin frame emerging from the gloom at the bend of the stairs. He was wearing jogging shorts and tennis sneakers.

He paused on the last step and inspected the situation with his peculiar remove, as if peering through a keyhole. After a while, he said, “I am running also,” his thick Hungarian accent stretching out the first syllable, “aaaalso.” It was an insistence, not an offer. I didn’t want company. A bit of doggerel, picked up who knows where, spooled in my head.

Yesterday, upon the stair,

I met a man who wasn’t there

He wasn’t there again today

I wish, I wish he’d go away …

I pushed through the screen door, my father shadowing my heels. The air was fat with humidity. Tar bubbles blistered the blacktop. I poked them with the toe of one sneaker while my father deliberated, turning first to his old VW camper, then to the lime-green Fiat convertible he had recently purchased, used, “for your mother.” My mother didn’t drive. “Waaall,” he said after a while. “We’ll take the Fiat.”

We drove the five-minute route in silence. He wheeled into the lot of the IBM Research Center, a block from our destination. Prominent signs made clear that parking was for employees only. My father paid them no mind. He took a certain pride in pulling off small scams, which he called “getting awaaay with things,” a predilection that led him to swap price tags on items at the local shopping center. He acquired a camping cooker in this manner, at a savings of $25.

“Did you lock your door?” my father asked as we headed across the lot, and, when I said I had, he looked at me doubtfully, then turned and went back to check. The flip side of my father’s petty transgressions was an obsession with security.

We hoofed it down the treeless corporate drive to Route 202, the thoroughfare that runs along the north edge of the park. We dodged between speeding cars to the far side, and climbed over the metal divider, jumping down into the depression beyond it. My father paused. “It happened there,” he said. He often talked this way, without antecedents, as if mid-conversation, a conversation with himself. I understood what “it” was: some months earlier, after midnight, teenagers returning from a party had run the stop sign on Strang Boulevard and collided with another car. Both vehicles had hurtled over the divider and landed on their roofs. No one survived. A passenger was decapitated. My father had been witness not to the accident itself but to its immediate aftermath. He was on call that night with the Yorktown Heights Ambulance Corps.

My father’s eagerness to volunteer for the local emergency medical service had seemed out of character, at least the character I thought I knew. He shrank from community affairs, from social encounters in general. On the occasions when my parents had guests, my father would either sit mum in his armchair or take cover behind his slide projector, working his way through tray after tray of Kodachrome transparencies of our hiking expeditions, naming each and every mountain peak in each and every frame, recounting every twist and turn in the trail, until our visitors, wild with boredom, fled into the night.

He referred to his service with the ambulance corps as “my job saaaaving people.” Which I also didn’t understand. Our town was a place of non-events, the 911 summons a suburban emergency: a treed cat, a housewife having an anxiety attack, an occasional kitchen-stove fire. The crash in Mohansic State Park was an exception, although again there was no one to save. When my father arrived, the police were covering the bodies. The ambulance driver grabbed his arm. “Steve, don’t look,” my father recalled him saying. “You don’t want that in your memory.” The driver had no way of knowing the wreckage already lodged in my father’s memory, and of how hard he had worked to erase it.

Leaving the old accident site behind, the two of us took off running along the paved road and into the picnic area, past rows of empty parking lots. The route began on a dull flat stretch of baseball diamonds and basketball courts, then looped around the giant public pool (where I worked summers at the snack stand) and along Mohansic Lake, finishing up a long hill. By the lake, we picked up a narrow footpath. We ran without speaking, single file.

At the final climb, the path gave way to wider pavement, and we began jogging side by side. Minutes into the ascent, he picked up his pace. I sped up. He ran faster. So did I. He pulled ahead again, then I did. We both gasped for breath. I looked over at him, but he didn’t return my gaze. His skin was scarlet, shiny with sweat. He stared straight ahead, intent on an invisible finish line. All the way up the hill, the fierce mute maneuvering maintained. When the pavement flattened, I ached to ease the pace. My stomach was heaving and my vision had blurred. My father broke into a furious stride. I tried to match it. It was, after all, the early ’70s; “I Am Woman (Hear Me Roar)” played on the mental sound track of my morning jogs. But neither my ardor for women’s lib nor my youth nor all my training could compete with his determination.