Полная версия:

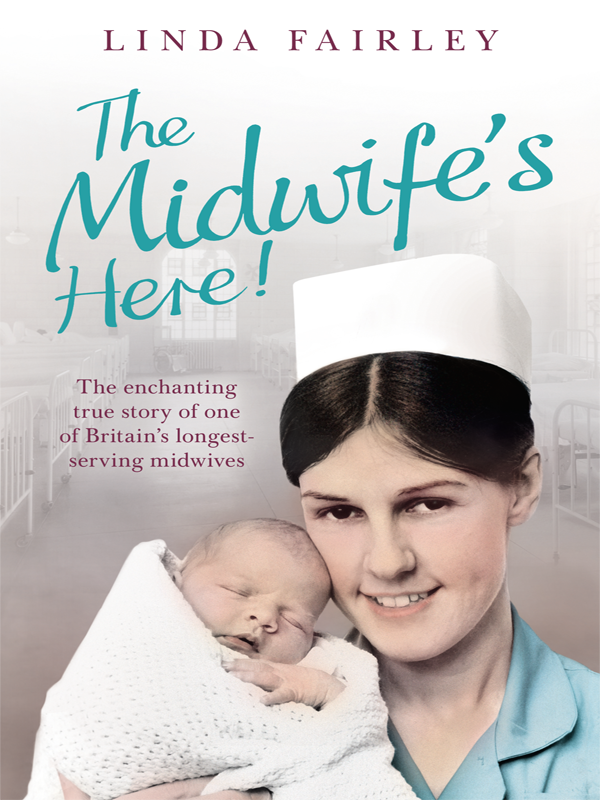

The Midwife’s Here!: The Enchanting True Story of One of Britain’s Longest Serving Midwives

Linda Fairley

The Midwife’s Here!

The Enchanting True Story of One of Britain’s Longest Serving Midwives

Copyright

This book is a work of non-fiction based on the author’s experiences.

In order to protect privacy, names, identifying characteristics, dialogue and details have been changed or reconstructed.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

and HarperElement are trademarks of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

Published by HarperElement 2012

Linda Fairley asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

THE MIDWIFE’S HERE. © Linda Fairley 2012. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780007446308

Ebook Edition © APRIL 2012 ISBN: 9780007446315

Version 2016-10-17

Dedication

For Peter, who told me I could write this book.

He was so proud of me, and I know he’d have loved it.

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

Preface

Chapter One

‘It feels like we’re in the Army!’

Chapter Two

‘I really am becoming an MRI nurse!’

Chapter Three

‘I didn’t expect to be looking after people who are actually ill’

Chapter Four

‘People are dying … This is harder than I thought’

Chapter Five

‘I have come to tender my resignation, Matron’

Chapter Six

‘Nurse Lawton, you have been granted permission to witness a birth if you come quickly’

Chapter Seven

‘Unless you ladder your stockings, to my mind you haven’t made a good job of dealing with a cardiac arrest!’

Chapter Eight

‘T’ Eagle ’as landed’

Chapter Nine

‘To qualify as a midwife you’ll need to deliver forty babies in ten months’

Chapter Ten

‘Feeling the warmth of a baby’s head in your hands, that new life, I’d honestly never experienced anything like it’

Chapter Eleven

‘Knickers and tights off, ladies!’

Chapter Twelve

‘Get these birds out of here, NOW! Where’s the hygiene? Tell me that!’

Chapter Thirteen

‘So you’ve had the baby? … Let’s have a cup of tea and a cigarette then’

Chapter Fourteen

‘She’s at top o’ stairs!’

Chapter Fifteen

‘He’s not touching her privates!’

Chapter Sixteen

‘Your baby is showing signs of life … He’s alive!’

Picture Section

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Read an excerpt from Linda Fairley's new book

Copyright

About the Publisher

‘Go, and do thou likewise.’

Prologue

‘The midwife’s here!’ Mick Drew exclaimed, nudging his wife Geraldine as I approached her bedside.

Mick gave me a broad smile that was filled with a mixture of gratitude and relief. It was a look I was growing accustomed to seeing on the faces of husbands with expectant wives, and I had learned that the more imminent the birth, the more appreciative and thankful the smile became.

It was early 1971 and Geraldine was about two months away from giving birth, but she was in the highly unusual position of expecting naturally conceived triplets, which no doubt more than trebled her loving husband’s concern.

‘Flamin ’eck, how long? I’ll go round the twist!’ Geraldine had balked when I outlined her birth plan a few months earlier, explaining that her multiple pregnancy automatically meant she would be admitted to the antenatal ward in Ashton General Hospital for bed rest when she was seven months pregnant.

‘That’s the rule, I’m afraid,’ I explained, thinking it was unfortunate Geraldine wouldn’t benefit from our brand new maternity unit, which wasn’t due to open until the end of the year. ‘Don’t you worry, we’ll take good care of you in here and I’m sure you’ll enjoy the break.’

Geraldine tittered. ‘Well, I suppose rules is rules, though I’m not sure how my old man will take it!’

She and Mick already had three young children, and quite how he was going to cope alone with them while his wife was in hospital was not yet apparent.

‘I suppose it’ll be good training for him,’ Geraldine said cheerfully the last time I saw her at antenatal clinic. ‘Seeing as how we’re going to end up with six! He’ll have to get used to doing his share and keeping an eye on three of ’em.’

I was pleased to see Geraldine had an easy-going nature and was quick to see the funny side of life. She would doubtless need those qualities to cope with a brood that size.

‘As for me, I’ll just have to get meself a pile of good mags to keep me busy, won’t I?’ she winked. ‘I’m sure I’ll cope.’

It hadn’t taken Geraldine long to settle herself into the antenatal ward, aided amiably by Mick, who was a round, ruddy-cheeked man who visited often and had such a spring in his step he appeared to bounce down the corridor, flared brown trousers swishing round his ankles.

Every day he wheeled in a little tartan shopping trolley of provisions for his wife and greeted her by planting a huge kiss on both cheeks, and then on the lips. ‘One for each baby,’ he always beamed before handing Geraldine a packet of sweets or a paper bag containing drinks and magazines.

‘How’s she doing, Nurse?’ he always asked me earnestly. ‘Everything as it should be?’

‘Yes, everything seems fine,’ I reassured him. ‘Your wife is doing very well indeed.’

‘Terrific!’ he grinned. ‘She’s a coper, my Geraldine, that she is.’

‘In’t he a smasher, Nurse?’ Geraldine would often say after his visits. ‘I’ve got meself a real diamond in Mick, that’s for sure.’

I got so used to seeing Geraldine plumped up on a pillow, swathed in a garish purple satin nightgown Mick had bought her at Stockport market, that after just a few weeks it felt as if she’d always been with us. Sometimes she even talked the nurses into letting her help out with the tea trolley, dishing out cuppas to other patients.

‘Does me good to stretch me legs,’ she’d grin as she waddled round the ward shouting out, ‘Two sugars as usual, Mrs Crowe? Best keep your strength up!’

‘Evening, Nurse!’ she’d always bellow when I turned up for a shift. ‘How are you tonight?’

‘It’s me who should be asking you that,’ I’d laugh, marvelling at how much energy Geraldine had in her condition. ‘I’ll be round later, make sure you’re OK.’

When a woman is expecting triplets she is at greater risk of developing high blood pressure, protein in the urine and oedema of the ankles, all of which are complications that can threaten the safety of the mother and baby.

I knew Geraldine wasn’t averse to sneaking to the toilets for a cigarette because I often smelled it on her breath, so I was always very particular about checking her blood pressure, in case smoking affected it.

Mick smuggled in the cigarettes, usually hidden in the paper bag he brought beneath a bottle of Vimto, a copy of Woman’s Weekly and a quarter of pineapple cubes from the corner shop. He tried to be fairly discreet about the cigarettes, but Geraldine didn’t really care if she got caught smoking, and often left empty packets and dog ends on the locker beside her bed.

One night as I sat beside Geraldine for a routine blood pressure check, I asked her how she was feeling being stuck in hospital for so long.

‘Right as rain,’ she chirped. ‘To tell you the truth, you were right. I’m enjoying the rest.’

Lowering her voice and staring down at her wedding ring, she added bashfully: ‘I’m glad I don’t have to face ’im indoors all the time, too.’

‘Whatever do you mean?’ I asked. ‘Mick thinks the world of you, and I thought you said he was a diamond?’

Geraldine leaned her head towards me conspiratorially and fixed her big green eyes on mine. They were glinting with what looked like a mixture of fear and excitement.

‘Can you keep a secret, Nurse?’ she whispered.

Before I had a chance to answer, Geraldine was mouthing the words: ‘They’re not his!’ As she did so she pointed dramatically to her pregnant belly, which was now so huge it looked fit to burst at any moment.

My eyes felt as if they were bulging out of their sockets, but I tried my best to remain calm and composed in the face of such alarming and unexpected news.

‘Well, I don’t know what to say,’ I blushed. I could feel the colour rising in my cheeks in preparation for her inevitable explanation and confession.

‘You see, Nurse, I’m not proud of it, but I went out to a dance in Tarporley and got drunk. I was on those Cinzano and lemonades. Not used to ’em. I had a one-night stand and, trust my luck, I landed up with triplets! Can you believe it?’

She chuckled half-heartedly while I gaped open-mouthed and shook my head.

‘No, nor could I, especially when I missed my next period and worked out the dates. Mick had been away, you see, got a big job laying Tarmac on the new motorway in Lancaster. You won’t say anything, will ya, Nurse?’

I patted her hand and gave her a big smile. ‘Course not,’ I said. ‘Why would I? Looks like he loves you to bits. I wouldn’t dream of interfering. Now come on, get some sleep. Those babies could come any day now you’re thirty-five weeks pregnant.’

I was absolutely stunned by Geraldine’s revelation, and not altogether certain I’d done the right thing in playing down her infidelity. It wasn’t my place to judge her, of course, but now I felt complicit in the deceit and I wished she’d never confided in me. That said, I found it impossible to be cross with Geraldine. She was such a likeable woman, as down to earth as they come. Her secret was safe with me.

The following night I arrived for duty on the labour ward to find an ashen-faced Mick pacing the corridor and dragging urgently on a cigarette, his brow deeply furrowed. For an awful moment I feared he’d found out the terrible truth, but he brightened immediately when he saw me and said: ‘It’s very good to see you, Nurse.’

It seemed Geraldine was in labour, several days earlier than anticipated.

‘Look after her, won’t you, Nurse?’ Mick added, giving me a friendly wink. ‘She’s the love of my life, you know.’

His words brought a tear to my eye, but it was a happy tear. His sentiments put everything in perspective. He and Geraldine loved each other and they were stuck together like glue. Wasn’t that what mattered most? I thought so, and I dearly hoped so.

As Geraldine had been in hospital for practically two months we were well prepared for the triplets’ birth. The theatre was ready in case she needed a Caesarean section, but the consultant had decided to give her every opportunity to deliver the babies naturally, as that was the preferred option in the early Seventies, provided there were no complications. We had a team of staff briefed and raring to go, and there had been quite a buzz around the maternity unit for weeks now as we all looked forward to this moment.

I was very proud to have been chosen as one of the three midwives who would each deliver a triplet. It was unusual to have more than one midwife involved, but that was what the doctors had decided on this occasion. I was delighted to have a starring role in the proceedings, and I was also very pleased to have arrived for my shift in good time, while Geraldine was in the first stage, still labouring.

I quickly pinned on my cap, tied on a clean apron and gathered my notes before marching as briskly as my legs could carry me to the delivery room.

Geraldine spotted me the second I walked through the door. ‘Glad you’re here, Nurse!’ she roared between hefty contractions that made her face contort beyond recognition.

Also gathered were two other duty midwives, Jill and Sheila, two trainee doctors I had never met before and two nurses I recognised from theatre and the neonatal unit.

I watched intently as the consultant, Dr Cooper, listened with an ear trumpet for three babies’ heartbeats and announced to the room he was extremely pleased to report they all sounded strong and healthy.

My own heart rate was raised at the excitement of the occasion, but I wasn’t nervous. Geraldine was a model patient – that’s if you discount her frequent, ear-splitting cries of ‘Bloody hell!’ and ‘Flamin’ ’eck!’

She gestured for me to take her hand, and each time another contraction came she squeezed so hard I thought she’d cut off my circulation. We spent about two hours going through the same routine of screaming and hand squeezing and, as the labour increased, so too did the volume of Geraldine’s cries and the strength of her already vice-like grip.

To help her cope with the pain she sucked on gas and air, which was attached to a big cylinder labelled ‘Entonox’. We were ready to give her a shot of the painkiller Pethidine should she require more relief, but in the event her labour progressed so quickly and Geraldine was doing so well, there was no need. At about 11 p.m. the birth began in earnest, with the head of the first of the three babies visible, ready to be delivered.

‘I can see baby’s head. It’s time to push,’ I said.

‘About bloody time. Aaaaarrrghhhh!’ growled Geraldine, before pushing out baby number one beautifully, straight into my hands. It was an absolute joy to see she was a perfect little girl who was so fair she looked as bald as an egg.

As I set about cleaning the screaming baby, who was clearly in no need of resuscitation, I realised Dr Cooper had stepped in to deliver the second baby. He told us it was intent on coming out bottom-first, which wasn’t what we’d wanted. Of course, having no scanning equipment in those days and only using our hands to palpate the abdomen and feel the position of the babies, it had been very difficult to gauge accurately how the triplets were lying.

I glanced at my colleague Jill, who had been meant to deliver baby number two. She looked disappointed, but we all knew that a doctor had to deal with a breech birth in these circumstances. Midwives are there to deliver babies under normal conditions, and this was a complication in an already unusual pregnancy.

Somewhere amid Geraldine’s now blood-curdling screams and the hushed but firm instructions being issued by Dr Cooper, I heard the words: ‘Well done. It’s a boy!’

By now baby number three was obviously in a hurry to meet its siblings. ‘Cephalic’ I heard almost immediately, and breathed a sigh of relief. That meant this one was head first, thank goodness. ‘And another girl! Congratulations, Mrs Drew!’

I looked at Geraldine’s exhausted face and her eyes met mine. Often during a delivery the mother will seek out one individual for reassurance. Nowadays it is usually the husband, but with Mick still pacing the corridor outside, as expectant dads did back then, Geraldine looked to me in this room full of people.

‘Well done,’ I whispered. ‘You’ve done it!’

It was only then she allowed a smile to stretch across her face. Despite her brave banter, she had been as apprehensive as the rest of us about this tricky delivery. So much might have gone wrong. Three babies meant three times the potential problems – and some.

‘Are they all OK?’ Geraldine puffed as I helped clean the babies up and arrange them in three cots around her bed.

‘They sound it!’ I laughed as the trio struck up a hearty chorus. They were captivating, they really were. Each one was perfect and pink and utterly gorgeous. ‘And I can count thirty fingers and thirty toes,’ I added, looking adoringly at each one in turn. ‘They are wonderful! Shall I get Mick?’

‘Yes please,’ she nodded proudly.

I have never seen a man look as delighted and besotted as Mick did that day.

‘Well, what d’ya reckon?’ Geraldine asked as he stepped into the room, his dancing eyes not knowing which cot to peer into first.

‘I’m as chuffed as mint balls!’ he said, smothering Geraldine with kisses before going up to each cot in turn and cooing over his babies. ‘Chuffed as mint balls!’

It was wonderful to witness a show of such pure, unadulterated joy and love. My heart went out to the Drews. They were now responsible for six children under the age of seven. Geraldine had already told me that Mick’s wage only just supported them as a family of five, let alone eight. Now they would somehow have to find room for three more little mites in their small semi-detached house. With Geraldine not able to drive and certainly not able to afford a vehicle big enough for her family even if she wanted to, she would have to go everywhere on foot. She would be practically housebound, I realised, with a sudden pang of worry. How would they manage?

Looking at the Drews, who were now holding hands tenderly and gazing at their triplets through dewy eyes, you would never have guessed their world was anything less than perfect. The babies had been delivered safely and each one looked a picture of health. To them, nothing else mattered in that moment, and I was absolutely thrilled for them.

Geraldine and her babies spent ten more days with us. We placed three cots around her bed on the postnatal ward, and at night all three babies were taken to the nursery, where I would often feed one with a bottle while rocking the other two in their cots using my feet.

I felt sad when I finally said goodbye to Geraldine. Despite her smoking and cursing and despite what she had done behind her husband’s back, she was a very nice woman who had a heart of gold, and I knew I would miss her. I still felt uneasy about the deceit, of course. I desperately wanted things to work out for the Drew family and I couldn’t help worrying about what might happen if Mick ever discovered his wife’s guilty secret.

‘Daddy, baby Michael looks the spit of you!’ one of the young Drew boys had exclaimed during an evening visit. ‘Look at his big ears! He has your nose too!’

‘What do you think, Nurse?’ Mick said, directing a piercing gaze at me, which he held for longer than was comfortable.

‘Don’t ask me!’ I laughed, sounding rather too jolly and wishing myself far away. ‘All I know is you’re a very lucky man, Mr Drew,’ I added hastily as I busied myself writing up notes.

‘I know, and my wife’s a lucky girl,’ he said, giving me one of his twinkling winks and smiling a wide, knowing smile. ‘A very lucky girl indeed.’

He was a card all right, just like Geraldine. They made a good pair and I hoped they made it, I really did.

It wasn’t until I was heading home after my shift that something dawned on me. Maybe Mick was trying to tell me something that night? I wondered if he knew the truth all along, or at least suspected it, yet he loved his wife so much he wasn’t going to let it spoil a thing? He was a proud and staunch family man, perhaps so much so he was prepared to keep his wife’s secret and raise another man’s children. It was possible the only thing he wasn’t comfortable with was allowing the midwife to think she knew more than he did himself about his personal life.

‘A couple of cards all right,’ I chuckled to myself when the pieces of the puzzle fell into place in my mind. ‘Good luck to them.’

Preface

To this day, the story of Geraldine Drew and the birth of her triplets remains one of my all-time favourites. It encapsulates the role of a midwife as a professional assistant and confidante, whose ultimate aim is to help women deliver babies safely into the world, whatever the circumstances.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a midwife as ‘a nurse (typically a woman) who is trained to assist women in childbirth’. Over the decades, I have learned that there are many, many different ways a midwife can assist a woman in childbirth and, believe you me, plenty of them are not listed in midwifery textbooks!

When I started my nursing training in 1966 at the Manchester Royal Infirmary (MRI) I had no idea what I was letting myself in for, or even that I would become a midwife. I have since delivered more than 2,200 babies and I still tingle with excitement at every birth. Just feeling the warmth of a newborn’s head in your hands, that new life, there’s honestly nothing like it.

In 2010 I celebrated forty years as a qualified midwife, becoming Britain’s longest-serving midwife at the same hospital. Today, I marvel at how much, yet also how very little, has altered over the years. I’ve witnessed countless changes in the NHS and in midwifery practices, from the demise of the old Nightingale wards to incredible breakthroughs in pregnancy drugs and IVF. I’ve seen fashions for routine enemas, bottle-feeding and home births come and go, and I’ve watched the reluctant shuffle of dads into antenatal classes and delivery suites turn into a stampede.

There have been nine changes of government during my career, so I’m told, but I have never let politics get in the way of delivering babies. I have been very happy sailing along in the great old liner that is the NHS, quietly navigating sea changes in bureaucracy, funding, practices and guidelines. I’ve never aspired to rise up the ranks and become a manager. Delivering babies and striving to make every pregnant woman feel like the most important pregnant woman in the world is what I do best.

Last year I had the honour of being my daughter’s midwife during her pregnancy, and I am now a very proud grandmother. Baby Joel was born prematurely in July 2011 as I was working on this book and also mourning the death of my third husband, Peter.

So much has happened over the years that I could not fit my memoirs into one volume, and this book concentrates on the early years of my career in the late Sixties and early Seventies. That means the story of Joel’s nerve-racking birth, along with so many others, will have to wait.

As you read this first instalment, I will keep laughing and crying, remembering and writing.

Chapter One

‘It feels like we’re in the Army!’

‘My job is to make nice young ladies of you all,’ Sister Mary Francis proclaimed. She was the headmistress at the strict Harrytown High School I attended in Romiley, Cheshire, and this was a phrase I heard countless times from the age of seven.

The private, all-girls convent school was very highly regarded and, like many of my peers, I came from a comfortable, middle-class family. It was expected that we ‘young ladies’ would enter suitably respectable employment at the age of eighteen, which I gathered meant choosing between working in a bank, going into teaching or becoming a nurse.

I was seventeen years old when I was summoned to Sister Mary Francis’s imposing dark-wood office and asked the question: ‘Well, Linda, what do you propose to do next?’ Before I could answer, she tilted her head forward to peer at me over her small, round reading glasses and said gravely: ‘You are indeed a fine young lady, despite the one minor indiscretion we have thankfully overcome. I trust you have chosen wisely.’