Полная версия:

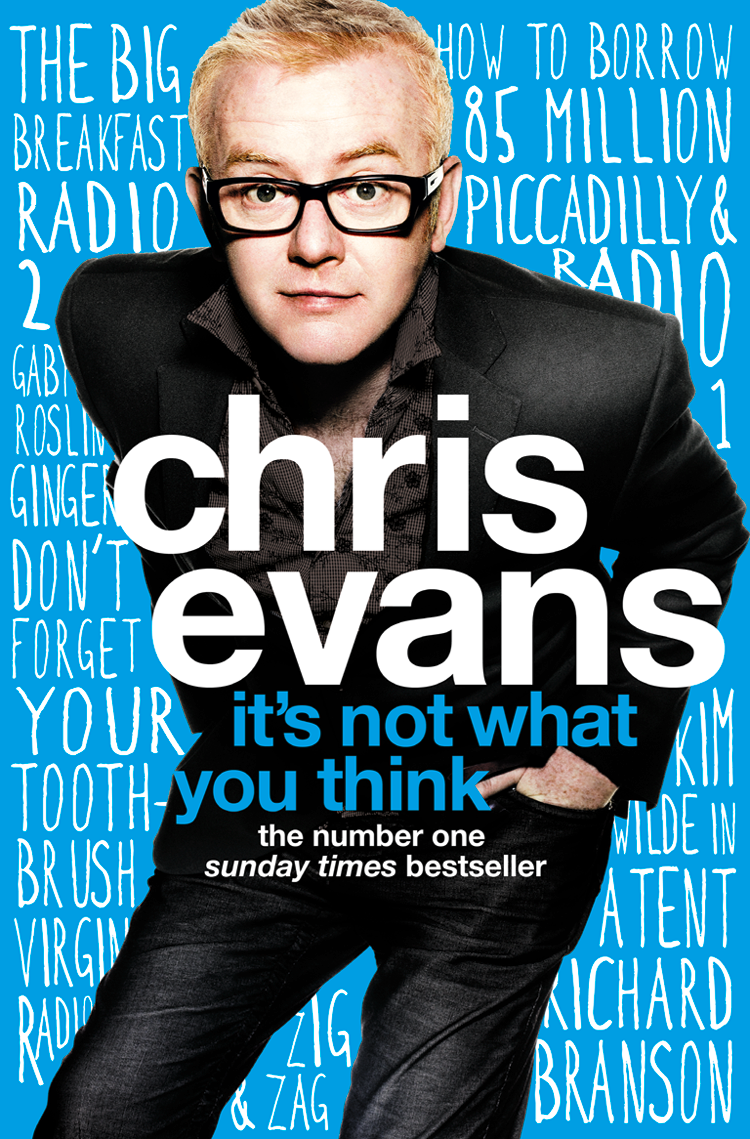

It’s Not What You Think

It's Not What You Think

Chris Evans

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2009

© Chris Evans 2009

Chris Evans asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein, the publishers would like to apologise for any omissions and will be pleased to incorporate missing acknowledgements in any future editions.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007327218

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2009 ISBN: 9780007327256

Version: 2017-05-04

To everyone that’s ever helped me, tolerated me, loved me, laughed with me, cried with me, created with me and forgiven me at any time, anywhere. Thank you.

Note to Reader

Dear Reader,

For the purposes of bespoke compartmentalisation during the course of this book, where Dickens went for episodes, Shakespeare went for stanzas and the Good Lord himself for chapter and verse, being a DJ I have gone for Top 10s.

If it was good enough for Moses and his Commandments, it should be good enough for my book.

CE

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Note to Reader

Preface

Prologue

Part One Mum, Dad and a Girl Called Tina

Top 10 Basic Facts about Christopher Evans

Top 10 Things I Remember about My Dad

Top 10 Best Things about Mrs Evans Senior

Top 10 Double Acts

Top 10 Resounding Memories of Primary-school Life

Top 10 Tastes, C. Evans, 1966-86

Top 10 First Memories of Going to School

Top 10 Weird Things about Teachers from a Kid’s Point of View

Top 10 Deaths

Top 10 Favourite Jobs (Other than Showbiz)

Top 10 Bosses I’ve Worked For

Top 10 Treats

Top 10 Girls—Actually Women—I Thought about Before I Had My First Girlfriend

Top 10 Schoolboy Errors

Top 10 Things I’m Rubbish at

Top 10 Things that Freak Me Out

Top 10 Things I Remember from School Lessons

Part Two The Piccadilly Years

Top 10 Best DJs I Have Ever Heard

Top 10 First Commercial Radio Stations in the UK

Top 10 Most Significant Cars in My Life

Top 10 Items of Technology in the Evans Household, circa 1983

Top 10 Things to Consider When Attempting to Make a Move in Your Career

Top 10 Things a Boss Should Never Do

Top 10 Things to Do When the Cards Are Stacked Against You

Top 10 Business Names I Have Been Involved in

Top 10 Dance Floor Fillers for Mobile DJ C. Evans circa 1985

Top 10 Memories of the great Piccadilly Radio exponential learning curve

Top 10 Things that Will Happen to You and that You Will Have to Accept

Top 10 Genuine Names of 80s Nightclubs in the North West of England

Top 10 Stars Recognised by a Single Name

Top 10 Records I remember from My Piccadilly Radio Days

Top 10 Things Never to Joke about on the Air

Top 10 Christmas Presents

Part Three Fame, Shame and Automobiles

Top 10 Things No One Tells You about London

Top 10 Legends I Have Worked With

Top 10 Books that Have Inspired Me and at Times Kept Me Sane

Top 10 Jobs at a Radio Station—in My Very Biased Opinion

Top 10 Pivotal Moments in My Career

Top 10 Things that Make a Successful Radio Show (the type of shows I do, that is)

Top 10 Seminal Items of Technology that Had the World Aghast

Top 10 Pads

Top 10 Things to Take to a Meeting if You Think You are Going to get Shafted

Top 10 Memories of The Big Breakfast

Top 10 Female Pop Stars

Top 10 Things to Consider When You Split Up with Someone

Top 10 Songs Regularly Murdered at Karaoke

Top 10 TV Shows

Top 10 Expletives

Top 10 Great Questions to be Asked

Top 10 Reasons to Stay Friends with Your Ex

Top 10 Memories of Radio 1

Top 10 Bands on Radio 1 During Our Watch

Top 10 TFI Moments

Top 10 Things that are True about Showbiz

Top 10 Signs You Are Losing the Plot

Top 10 Things a Celeb Should Never Do

Top 10 Things I Think About—Other than My Wife and Family

Top 10 Offers I Have Declined

Top 10 Best Bits of Advice

Top 10 Most Useless States of Mind

Top 10 Things that Help Get a Deal Done

Top 10 Mantras

Top 10 Things People Put Off

Top 10 Reasons Why I Presume Capital Never Took Us Seriously

Top 10 Human Responses I Experienced Leading up to the Deal

Top 10 Houses I Have Found Myself In For One Reason Or Another

Keep Reading

Appendix it is what you think…notes from the cast

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

Preface

Top 10 Tabloid Newspaper Descriptions of Me

10 GENIUS

9 WHIZZ KID

8 MOGUL

7 MOTORMOUTH

6 UGLY

5 MEGLOMANIAC

4 DRUNKARD

3 TYRANT

2 LIAR

1 TOSSER

As you can see there have been countless occasions when I have done myself few favours in the public eye. After some deep thought and consideration on the road back to the real world, I can only conclude that this was because I reached the top of a mountain I never even expected to climb. Once there it’s obvious to me now that I didn’t have the first clue what to do next—so I jumped off.

‘Far more fun than merely walking back down and having a rest before setting off in search of the next one,’ I thought.

Wrong!

As a thirteen-year-old paperboy I never for a second imagined the tabloids I was then delivering would one day take me into their beloved bosom and splash me on their front covers with such regularity and for such varying reasons. Some good, some bad, some true, some fittingly published, but that’s all part of the deal. Anyone that complains about it—famous people that is—have to realise they can’t have their cake and eat it. The fatal mistake is to moan—if you don’t like the bright lights and everything that comes with them, get off the stage.

For years, as the song went, I did it my way; for years I thought I was bomb-proof; for years I was just plain lucky when I thought I was being a wise guy. Of course I got things wrong from time to time, but I put that down to being part of life’s rich tapestry—after all, few of us set out to get things wrong on purpose.

In the first half of my life—at least I hope it’s only been the first half of my life—I achieved everything I ever aspired to. I performed a job that I loved, I punched way above my weight when it came to dating the opposite sex, I worked with and met some of the most talented and exciting people on the planet, I bought cars and houses that were to die for and at one time I was co-owner of a company that was worth over a billion pounds. Yet here I am, sat back in front of the keyboard with a cup of tea, wondering just how on earth any of this happened.

Was there a plan? Not that I’m aware of, but then again I suppose there must have been—surely a story like this couldn’t occur by chance? Or maybe that’s what life is: just one big accident from start to finish and what comes round the corner to hit us depends on which road we’re on at the time.

Ultimately I look back and see a minefield of huge risks and high stakes in all aspects of my life, some of which went my way, some of which did not, but most of which I didn’t have to take in the first place, yet I still felt compelled to do so. Barring physical, mental and social disadvantages, I think this is the single most common theme that links people who might be more likely to exceed their so-called ‘expectations’ as opposed to those who don’t.

I am constantly intrigued by this existence of ours and why we are here at all in the first place and therefore, as a result, I am fascinated as to just how far we can take things before we are asked to leave. I also don’t want to leave; I love being alive and here and breathing and laughing and crying and loving and feeling, and so I have tried to grab every day by the scruff of the neck and wring it out for all it is worth. (Often to the detriment of my own well-being as well as to the exasperation of those around me.) But I’m sorry, I just can’t help it: that’s the way I am. Anyone who has a half- decent life and doesn’t wonder on a daily basis about the magnificence and irony of being a human being I simply cannot comprehend. Life is too fantastic to ignore.

Along this path of frustration and wonderment I have been lucky enough to achieve what many consider to be a reasonable level of success in my professional life (if not in my personal life)—or at least that’s what I thought. I have since come to realise that real success is about the long term. There is no better way to prove yourself than to get better at what you do every day you do it.

There is no question I have made at least as many bad decisions as good ones, probably many more, and there’s plenty of evidence to prove it—losing a bunch of money for a start—£67 million pounds at the last count (not that I had much to start with, so let’s not dwell on that). But I have also learnt that it only takes one good break to turn your life around and launch you into a stratosphere you never even dared dream of.

If I had to sum up the difference between the good times and the bad, the bottom line is that when I have put the effort in I have reaped the rewards, and when I have failed to do so my life has stalled—on several occasions going into a complete flat spin. It really is as simple as that.

As far as I can see, life is one big bank account and the best philosophy is just to keep on making deposits whenever you can; be they financial, emotional, occupational, or otherwise. This is the absolute number one way to reduce the risk of disappointment, unhappiness, poverty and loneliness. By rights, I’m not at all sure I should even still be here to tell my tale, but by the grace of God I am, so here goes.

Prologue

Top 10 Stories Still

to Come…

10 How much is that chat-show host in the window?

9 How not to buy a national newspaper

8 The management have walked out—what do I do now?

7 Let’s give away a million pounds—hey, I’ve got an even better idea: let’s give away two

6 Macca and the maddest TFI moment of all

5 The £30,000 carrier bag

4 Gazza, the tour bus and a ‘convenient’ substitution

3 Quick, wake up—you’re 300 and something in the Sunday Times rich list

2 The £24-million cappuccino

1 Billie, the Doctor and a golfer named Natasha

Top 10 Basic Facts about Christopher Evans

10 Born 1 April 1966

9 In Warrington in the north-west of England

8 Mother Minnie (nurse)

7 Father Martin (wages clerk, former bookie)

6 Brother David (twelve years older—nursing professional)

5 Sister Diane (four years older—teaching professional)

4 Very bright

3 Reluctant student

2 Needed glasses but nobody knew for the first seven years of his life, which meant I couldn’t see a bloody thing at school (presuming this is what the world actually looked like)

1 Had fantastically red hair

Life for me growing up was no great shakes one way or the other. We were an average working-class family with an average working-class life. We weren’t poor but, looking back, we were much less well off than I had realised.

I was nought to start off with, but I quickly began to age and lived with my loving mum and dad, Minnie and Martin, and my elder brother and sister, David and Diane. Our house at the time was both a home and a business. We had a proper old-fashioned corner shop like the ones you see on the end of a terraced row of houses, just like in Coronation Street, some of which had those over-shiny red bricks that looked more like indoor tiles. This is my first memory of one-upmanship: we never had those bricks but what we did have was a thriving retail outlet. Our shop sold almost everything—at least that’s what my mum says—not like Harrods sell almost everything, like elephants and tigers and miniature Ferraris, but like a general store might sell almost everything, like chickens, shoelaces, cigarettes and liquorice.

I don’t remember the shop at all, to be honest, but I do remember the tin bath that we all shared on a Sunday night in the living room behind where the shop was. It was a heavy, old, silvery grey thing, rusty in parts, which was ceremonially plonked in front of the fire (for heat retention

purposes, I assume) before being filled by hand with scalding-hot water from the kettle boiled on the stove. This was then topped up with cold water via a big white jug, after which we took our turns bathing en famille.

I remember the outside toilet, the coal shed, Mr Simpson the greengrocer, and the rag and bone man—who I was a bit scared of—but if I’m honest that’s just about it, apart from how upset my mum was when the Council made a compulsory purchase, not only on our house and our shop, but on our whole street, not to mention hundreds of other houses around where we lived, to make way for something so instantly forgettable I’ve actually forgotten what it was.

As a result of this compulsory order we were forced to move to council housing and another part of town some three miles away, which for a working-class family was tantamount to emigrating to Australia. Although many years later my brother did emigrate to Australia and he assured me it was not the same at all.

For my part I wanted to break out of the council estate which we were forced to call home and where I was brought up mostly. From day one I felt compelled to escape those grey concrete clouds of depression.

The house we lived in was of no particular design, in fact it was of no particular anything. It was more nothing than something. In short, it was not the product of passion. Council estates don’t do passion, they just do numbers.

The estate I lived on didn’t even do bricks. Huge great slabs of pebble-dashed prison walls had been slotted together in rows of mediocrity as an excuse for housing. Housing for people with more pride in the tip of their little finger than the whole of the town planners’ hearts put together. People like my mum, who had survived the war as a young girl whilst simultaneously being robbed of her youth by having to work in a munitions factory. People like my dad and my uncle who had fought overseas to protect us from other kinds of Nazis.

How dare they ‘home’ these fine people in such an unnecessary hell?

It was waking up to this backdrop of pessimism and injustice every day that made my childhood blood boil. It was like the whole place had been designed to make you want to kill yourself. A curtain of gloom against a drama of doom. I hated the unfairness of it all.

Why did some people, for example, who lived not more than half a mile away, have a detached or semi-detached house that looked like someone may have actually cared about how it turned out? How come they had nice drives and nice cars and a pretty garden at the front and the back?

Not that I begrudged the owners of such places, or rather palaces as they appeared to me, on the contrary—good for them. I just thought things should be the same for my family.

The apathy of it all also drove me crazy. Why did people who lived on these estates all over Great Britain accept this as their lot? Why did mums and dads bother going to work each day to be able to pay the rent for these shitholes? The authorities should have been paying them to live there, with a bonus if they managed to make it all the way through to death.

So there you have it, that’s where my initial drive came from. It wasn’t that I was bullied at school or the early death of my dad, or any of the other predictable psychobabble reasons often wheeled out to explain success. It was purely and simply that I wanted a better life.

Top 10 Things I Remember about My Dad

10 The back of his neck creasing up on the top of his shirt collar

9 The fact that he never took me to a football match

8 His belly, which went all the way in if I pressed it with my finger

7 His vest-and-braces look

6 The smell of Brylcreem

5 His snooker-cue case

4 His handwriting (which was beautiful)

3 His smile

2 His voice

1 How much my mum loved him

Dad is, sadly, a faint and distant memory for me.

Although he was around for the first thirteen years of my life, I only have a few vivid recollections of him as a personality. I remember him mostly as being just a great dad. What else does a dad need to be?

He was, however, relatively old for a dad, especially in those days, and to be honest I wish he had been a bit younger. Having said that, I’m only a couple of years ahead of him now where my own son is concerned and if my wife and I are lucky enough to pop out another little sprog or sprogette any time soon, I will more likely than not be almost exactly the same age to our second child as my dad was to me.

But Dad was also older in his ways. He was a proud guy from a proud time who met my mum at a dance. Dancing was the speed-dating of its era, something we might want to learn from today.

Mum still says, ‘You can tell all you need to know about a man if you dance with him—proper dancing that is.’ And as the dance halls have disappeared while divorce rates have gone up, it looks like she may well have a point—she usually does.

Whatever Dad did on the dance floor that night, he obviously did it very much to my mum’s liking, as from that day onwards, right up until now, some thirty years after he passed away, my mum’s heart is still the sole property of one Mr Martin Joseph Evans.

My sister and I were once stupid enough to ask Mum if she had ever considered remarrying. She looked at us as if we had lost our minds—brilliant, beautiful and hilarious all at the same time.

Martin Joseph was a straight up and down suit-and-tie man for the majority of his waking hours. He was also a handsome bugger with a permanent tan which Mum insisted he received as a reward for serving with the RAF in Egypt during the war. I believed her—it was a cool story.

Dad worked hard every day except Sunday, leaving at the same time every morning and always arriving home at the same time every evening—a quarter past five, more than a minute or two after that and Mum would start getting worried whilst Dad’s tea would start getting cold.

He played snooker once a week, where he apparently enjoyed a pint and a half of bitter, but other than that, unless he had a secret life none of us knew about, that was him.

Except, of course, for the gee-gees.

Ah, now, there you have him. Dad loved the horses.

There’s a famous phrase that goes something like: when you want to know who wins on the horses you need to bear something in mind: the bookmakers have several paying-in windows but only one paying-out window. That should tell you all you need to know about where most of the money goes.

Not that this should have concerned Dad as he was indeed a bookie; he was the enemy and his betting story is the strangest I’ve ever heard. My dad’s entire bookmaking career both started and finished before I was born.

He set up his ‘bookies’ shop in the fifties with a pal of his, and by all accounts, particularly their own, they did pretty swift business—as most bookmakers do.

Warrington was a typical working-class town in those days, and many an honest man’s one and only indulgence was a flutter on the nags once or twice a week. Dad and his partner were happy to facilitate such flights of fancy—until, that is, one day when the frost came down.

This was no normal frost, however, but an almighty frost—a frost that would last not for days or weeks but for months. Four months, to be precise. All racing came to a halt and consequently all wagering. It was the steeplechase season, the favoured genre of the northern man, but the race courses fell silent, the jumps remained unchallenged, the stands stood empty.