Полная версия:

Whispers in the Sand

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in 2000

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

Copyright © Barbara Erskine 2016

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

Cover photographs © Sylvain Grandadam /Getty Images (feluccas on River Nile); Richard Jenkins Photography (woman)

Barbara Erskine asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007288649

Ebook Edition © March 2016 ISBN: 9780007320998

Version: 2017-09-07

Dedication

The quotations at the head of each chapter are adapted from

The Book of the Dead edited by E A Wallis Budge

Epigraph

THE WHITE EGRETITINERARY

Note: alterations to the schedule are subject to change without prior notice

Most evenings there are film shows and talks in the lounge bar on different aspects of ancient and modern Egypt

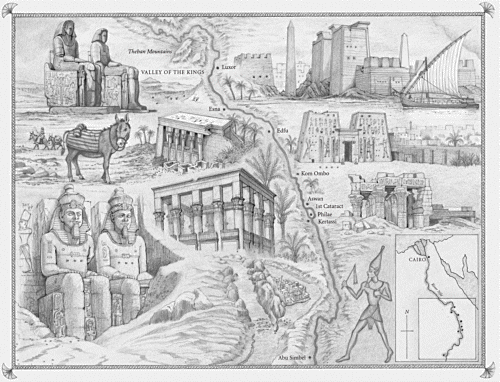

DAY 1: p.m. Arrival Dinner on board DAY 2: Visit the Valley of the Kings o/n Cruise to Edfu DAY 3: a.m. Visit the Temple of Edfu p.m. Cruise to Kom Ombo DAY 4: a.m. Visit the Temple of Kom Ombo p.m. Cruise to Aswan DAY 5: a.m. Visit Unfinished Obelisk p.m. Kitchener’s Island DAY 6: a.m. Aswan Bazaar midday: Aperitif at The Old Cataract Hotel p.m. Visit High Dam DAY 7: a.m. Sail on a felucca p.m. Free afternoon DAY 8–9: Optional 2-day visit to Abu Simbel (4 a.m. start) DAY 10: Return late afternoon Evening: Son-et-lumière, Philae Temple DAY 11: a.m. Visit Philae Temple. Cruise to Esna p.m. Esna Temple. Cruise to Luxor DAY 12: a.m. Temple of Karnac p.m. Temple of Luxor Evening: Pasha’s Party DAY 13: a.m. Luxor Museum and bazaar p.m. Papyrus Museum Evening: Son-et-lumière, Karnac Temple DAY 14: Return to EnglandThere can be little doubt that the first vessels of glass were manufactured in Egypt under the 18th dynasty, particularly from the reign of Amenhotep II (1448–20 BC) onward. These vessels are distinguished by a peculiar technique: the shape required was first formed of clay (probably mixed with sand) fixed to a metal rod. On this core the body of the vessel was built up, usually of opaque blue glass. On this, in turn, were coiled threads of glass of contrasting colour, which were pulled alternately up and down by a comb-like instrument to form feather, zigzag or arcade patterns. These threads, usually yellow, white or green in colour, and sometimes sealing-wax red, were rolled in (marvered) flush with the surface of the vessel. The vessels so made were nearly always small, being mainly used to contain unguents and the like.

Encyclopaedia Britannica

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Afterthought

Author’s Note

Keep Reading Barbara Erskine’s Novels

Keep Reading Sleeper’s Castle

About the Author

Also by Barbara Erskine

About the Publisher

Prologue

In the cool incense-filled heart of the temple the sun had not yet sent its lance across the marble of the floor. Anhotep, priest of Isis and of Amun, stood before the altar stone in the silence, his hands folded into the pleated linen of his sleeves. He had lit the noon offering of myrrh in its dish and watched as the wisps of scented smoke rose and coiled in the dimly lit chamber. Before him, in the golden cup, the sacred mixture of herbs and powdered gems and holy Nile water sat in the shadows waiting for the potentising ray to hit the jewelled goblet and fall across the potion. He smiled with quiet satisfaction and raised his gaze to the narrow entrance of the holy of holies. A fine beam of sunlight struck the rim of the doorframe and seemed to hover like a breath in the hot shimmer of the air. It was almost time.

‘So, my friend. It is ready at last.’ The sacred light was blocked as a figure stood in the doorway behind him; the sun’s ray bounced crooked across the floor, deflected by the polished blade of a drawn sword.

Anhotep drew breath sharply. Here in the sacred temple, in the presence of Isis herself, he had no weapon. There was nothing with which he could protect himself, no one he could call. ‘The sacrilege you plan will follow you through all eternity, Hatsek.’ His voice was strong and deep, echoing round the stone walls of the chamber. ‘Desist now, while there is time.’

‘Desist? When the moment of triumph is finally here?’ Hatsek smiled coldly. ‘You and I have worked towards this moment, brother, through a thousand lifetimes and you thought to deprive me of it now? You thought to waste the sacred source of all life on that sick boy pharaoh! Why, when the goddess herself has called for it to be given to her?’

‘No!’ Anhotep’s face had darkened. ‘The goddess has no need of it!’

‘The sacrilege is yours!’ The hiss of Hatsek’s voice reverberated round the chamber. ‘The sacred potion distilled from the very tears of the goddess must be hers, by right. She alone mended the broken body of Osiris and she alone can renew the broken body of the pharaoh!’

‘It is the pharaoh’s!’ Anhotep moved away from the altar. As his adversary stepped after him the purifying ray of sunlight sliced the darkness like a knife and struck the crystal surface of the potion turning it to brazen gold. For a moment both men stared, distracted by the surge of power released from the goblet.

‘So,’ Anhotep breathed. ‘It has succeeded. The secret of life eternal is ours.’

‘The secret of life eternal belongs to Isis.’ Hatsek raised his sword. ‘And it will remain with her, my friend!’ With a lunge he plunged the blade into Anhotep’s breast, withdrawing it with a grunt as the man fell to his knees. For a moment he paused as though regretting his hasty action, then he raised the bloody blade over the altar and in one great sweeping arc he brought it down on the goblet, hurling it and the sacred potion it contained to the floor.

‘For you, Isis, I do this deed.’ Setting the sword down on the altar he raised his hands, his voice once again echoing round the chamber. ‘None but you, oh great goddess, holds the secrets of life and those secrets shall be yours for ever!’

Behind him Anhotep, his bloodied hands clutching his chest, somehow straightened, still on his knees. His eyes already glazing over he groped, half blind, for the sword above him on the stone. Finding it he dragged himself painfully to his feet and raised it with both hands. Hatsek, his back to him, his eyes on the sun disc as it slid out of sight of the temple entrance never saw him. The point of the blade sliced between his shoulder blades and penetrated down through his lung into his heart. He was dead before his crumpled form folded at the other man’s feet.

Anhotep looked down. At the base of the altar the sacred potion lay as a cool blue-green pool on the marble, stained by the curdling blood of two men. Staring at it for a moment Anhotep looked round in despair. Then, his breath coming in small painful gasps, he staggered across to a shelf in the shadow of a pillar. There stood the chrismatory, the small, ornate glass phial in which he had carried the concentrated potion to the holy of holies. He reached for it, his hands slippery with blood and turned back to the altar. Falling painfully to his knees, sweat blinding his eyes, he managed to scoop a little of the liquid back into the tiny bottle. Fumbling with shaking fingers he pressed in the stopper as far as it would go, smearing blood over the glass. In one last stupendous effort he pulled himself up and set it down on the back of the shelf in the darkness between the pillar and the wall, then he turned and staggered out towards the light.

By the time they found him lying across the entrance to the holy place he had been dead for several hours.

As the bodies of the two priests were washed and embalmed the prayers said for their souls stipulated that they serve the Lady of Life in the next world as they had failed to serve her in this.

It was the high priest’s order that the two mummies be laid inside the holy of holies, one on each side of the altar, and that it should then be sealed for ever.

1

May there be nothing to resist me at my judgement; may there be no opposition to me; may there be no parting of thee from me in the presence of him that keepeth the scales.

It is thirteen hundred years before the birth of Christ. The embalming complete, the bodies of the priests are carried back into the temple in the cliff where once they served their gods and they are laid to rest in the shadows where they died. A mote of sunlight lies across the inner sanctuary for a moment, then as the last mud brick is pressed into place across the entrance, the light is extinguished and the temple that is now a tomb is instantly and totally dark. Were there ears to hear they would distinguish a few muffled sounds as the plaster is smoothed and the seals set. Then all is as silent as the grave.

The sleep of the dead is without disturbance. The oils and resins within the flesh begin their work. Putrefaction is held at bay.

The souls of the priests leave their earthly bodies and seek out the gods of judgement. There in the hall beyond the gates of the western horizon, Anubis, god of the dead, holds the scale which will decide their fate. On the one side lies the feather of Maat, goddess of truth. On the other is laid the human heart.

‘What you need, my girl, is a holiday!’

Phyllis Shelley was a small wiry woman with a strong angular face, which was accentuated by her square red-framed glasses. Her hair cropped fashionably short, she looked twenty years younger than the eighty-eight to which she reluctantly admitted.

She headed for the kitchen door with the tea tray leaving Anna to follow with the kettle and a plate of scones.

‘You’re right, of course.’ Anna smiled fondly. Pausing in the hall as her great-aunt headed out towards the terrace, she stood for a few seconds looking at herself in the speckled gilt-framed mirror, surveying her tired, thin face. Her dark hair was knotted behind her head in a coloured scarf which brought out the grey-green tones in her hazel eyes. She was slim, tall, her bones even, classically good-looking, her body still taut and attractive, but her mouth was etched with fine lines on either side now and the crow’s-feet around her eyes were deeper than they should have been for a woman in her mid-thirties. She sighed and pulled a face. She had been right to come. She needed a good strong dose of Phyllis!

Tea with her father’s one remaining aunt was one of the great joys of life. The old lady was indefatigably young at heart, strong – indomitable was the word people always used to describe her – clear thinking and she had a wonderful sense of humour. In her present state, miserable, lonely and depressed, three months after the decree absolute, Anna needed a fix of all those qualities and a few more besides. In fact, she smiled to herself as she turned to follow Phyllis out onto the terrace, there was probably nothing wrong with her at all which tea and cake and some straight talking in the Lavenham cottage wouldn’t put right.

It was a wonderful autumn day, leaves shimmering with pale gold and copper, the berries in the hedges a wild riot of scarlet and black, the air scented with wood smoke and the gentle echo of summer.

‘You look well, Phyl.’ Anna smiled across the small round table.

Phyllis greeted Anna’s remark with a snort and a raised eyebrow. ‘Considering I’m so old, you mean. Thank you, Anna! I am well, which is more than I can say for you, my dear. You look dreadful, if I may say so.’

Anna gave a rueful shrug. ‘It’s been a dreadful few months.’

‘Of course it has. But there’s no point in looking backwards.’ Phyllis became brisk. ‘What are you going to do with your life now it is at last your own?’

Anna shrugged. ‘Look for a job, I suppose.’

There was a moment’s silence as Phyllis poured out two cups of tea. She passed one over and followed it with a homemade scone and a bowl of plum jam, both courtesy of the produce stall at the local plant sale. Phyllis Shelley had no time in her busy life for cooking or knitting, as she constantly told anyone who had the temerity to come and ask for contributions of either to the church fete or similar money-raising events.

‘Life, Anna, is to be experienced. Lived,’ she said slowly, licking jam off her fingers. ‘It may not turn out the way we planned or hoped. It may not be totally enjoyable all the time, but it should be always exciting.’ Her eyes flashed. ‘You do not sound to me as though you were planning something exciting.’

Anna laughed in spite of herself. ‘The excitement seems to have gone out of my life at the moment.’

If it had ever been there at all. There was a long silence. She stared down the narrow cottage garden at the stone wall. Phyllis’s cat, Jolly, was asleep there, head on paws, on its ancient lichen-crusted bricks covered in scarlet Virginia creeper. Late roses bloomed in profusion and the air was deceptively warm, sheltered by the huddled buildings on either side. Anna sighed. She could feel Phyllis’s eyes on her and she bit her lip, seeing herself suddenly through the other woman’s critical gaze. Spoilt. Lazy. Useless. Depressed. A failure.

Phyllis narrowed her eyes. She was a mind reader as well. ‘I’m not impressed with self-pity, Anna. Never have been. You’ve got to get yourself off the floor. I never liked that so and so of a husband of yours. Your father was mad to let you get involved with him in the first place. You married Felix too young. You didn’t know what you were doing. And I think you’ve had a lucky escape. You’ve still got plenty of time to make a new life. You’re young and you’ve got your health and all your own teeth!’

Anna laughed again. ‘You’re good for me, Phyl. I need someone to tell me off. The trouble is I don’t really know where to start.’

The divorce had been very civilised. There had been no unseemly squabbles; no bickering over money or possessions. Felix had given her the house in exchange for a clear conscience. He, after all, had done the lying and the leaving. And his eyes were already on another house in a smarter area, a house which would be interior-designed to order and furnished with the best to accommodate his new life and his new woman and his child.

For Anna, suddenly alone, life had become overnight an empty shell. Felix had been everything to her. Even her friends had been Felix’s friends. After all, her job had been entertaining for Felix, running his social diary, keeping the wheels of his life oiled, and doing it, so she had thought, rather well. Perhaps not. Perhaps her own inner dissatisfaction had shown in the end after all.

They had married two weeks after she graduated from university with a good degree in modern languages. He was fifteen years older. That decision to stay on until she had finished her degree had been, she now suspected, the last major decision she had made about her own life.

Felix had wanted her to quit the course the moment he asked her to marry him. ‘You don’t need all that education, sweetheart,’ he had urged. ‘What’s it for? You’ll never have to work.’

Or worry your pretty little head about anything worth thinking about … The patronising words, unsaid but implied, had echoed more and more often through Anna’s skull over the ensuing years. She kidded herself that she had no time for anything else; that what she did for Felix was a job. It was certainly full time. And the pay? Oh, the pay had been good. Very good! He had begrudged her nothing. Her duties had been clear cut and simple. In these days of feminist ambition, independence and resolve, she was to be decorative. He had put it so persuasively she had not realised what was happening. She was to be intelligent enough to make conversation with Felix’s friends but not so intelligent as to outshine him and, with some mastery, she later realised, he had made it seem enormously important and responsible that she was to organise all the areas of his life which were not already organised by his secretary. And in order to maintain that organisation uninterrupted it was made clear only after the fashionable wedding in Mayfair and the honeymoon in the Virgin Islands that there would be no children. Ever.

She had two hobbies: photography and gardening. On both he allowed her to spend as much money as she liked and even encouraged her interest when it did not conflict with her duties. Both were, after all, fashionable, good talking points and relatively harmless and she had allowed them to fill whatever gaps there were in her life. Indeed in combining them she had become so good at both that her photographs of the garden won prizes, sold, gave her the illusion that she was doing something useful with her life.

Strangely, she had put up with his occasional indiscretions, surprised herself at how little they actually upset her and suspecting but never admitting that this was because, perhaps, she did not, after all, love him quite as much as she ought to. It did not matter. No other man came along to whom she was attracted. Was she, she sometimes wondered, a bit frigid? She enjoyed sex with Felix, but did not miss it when it became less and less frequent. Nevertheless, the news that his latest girlfriend was pregnant hit her like a sledgehammer. The dam, which had held back her emotions for so long, broke and a torrent of rage and frustration, loneliness and misery, broke over her head in a tidal wave which terrified her as much as it shocked her husband. He had not planned this change in his life. He had expected to carry on as before, visiting Shirley, supporting her, and when the time came paying, no doubt through the nose, for the child, but not becoming too involved. His instant and genuine enchantment with the baby had shaken him as much as it had pleased Shirley and devastated Anna. Within days of the birth he had moved in with mother and child and Anna had consulted her solicitor.

After the uncontested divorce Felix’s friends had been strangely supportive of her, perhaps realising that something unplanned and unexpected had taken place and feeling genuinely sorry for her, but as one by one they rang to give her their condolences and then fell into embarrassed silence she realised that in fact she had very few friends of her own and her feeling of utter abandonment grew stronger. Strangely, the one piece of advice they all passed on before hanging up, was that she take a holiday.

And now here was Phyllis, saying the same thing.

‘You must start with a holiday, Anna dear. Change of scene. New people. Then you come back and sell that house. It’s been a prison for you.’

‘But, Phyl –’

‘No, Anna. Don’t argue, dear. Well, perhaps about the house, but not about the holiday. Felix used to take you to all those places where you did nothing but sit by swimming pools and watch him talk business. You need to go somewhere exciting. In fact you need to go to Egypt.’

‘Egypt?’ Anna was beginning to feel her feet were being swept from beneath her. ‘Why Egypt?’

‘Because when you were a little girl you talked about Egypt all the time. You had books about it. You drew pyramids and camels and ibises and you pestered me every time I saw you, to tell you about Louisa.’

Anna nodded. ‘It’s strange. You’re right. And I haven’t thought about her for years.’

‘Then it’s time you did. It is so easy to forget one’s childhood dreams. I sometimes think people expect to forget them. They abandon everything which would make their lives exciting. I think you should go out there and see the places Louisa saw. When they published some of her sketchbooks ten years ago I was tempted to go myself, you know. I’d helped your father select the pictures, and worked with the editor over the captions and potted history. I just wanted to see it so much. And perhaps I still will one day.’ She smiled, the twinkle back in her eye, and Anna found herself thinking that it was entirely possible that the old lady would do it.