скачать книгу бесплатно

“Your absence would be noticed in a big way.”

Discreetly but unmistakably Max was referring to the conference in Chicago I had attended in January with my squadmates, one of whom, Juan, had used a company credit card for our six-thousand-dollar gentlemen’s club bill. Although he later called and finessed the charge down to a more realistic thirty-seven hundred dollars, and in spite of company policy not to reveal employee money matters, the story got out and the four of us were forced to give the Employee Conduct Board a lurid and damning account of our trip.

“Is Mr. Raven still here?”

“He left twenty minutes ago.”

“What about Mr. Grobalski?”

“Gone too.”

Max handed me my coat and I followed him out slowly.

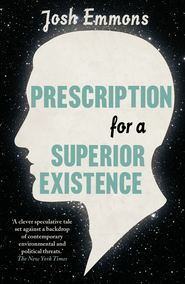

It’s hard to say if I would have been more open to the seminar if Danforth hadn’t hung over me that morning. I knew I could be more sensitive—as much as the next man, certainly—but I was wary of the involvement of Prescription for a Superior Existence. Maybe I shouldn’t have been. Beyond what was common knowledge, all I knew then about PASE was that its founder, Montgomery Shoale, a rich venture capitalist, had self-published The Prescription for a Superior Existence, a thousand-page book that introduced and explained the eponymous religion, nearly two decades ago, when it was widely considered a vanity project designed to lend depth and credibility to his company training seminars—he had built a reputation around the Bay Area for speaking about intra-office social cohesion and running more time-efficient meetings—until eventually PASE’s religious bona fides were established and the IRS granted it tax-exempt status as a faith-based organization. When the Citadel, the flagship building of its Portrero Hill headquarters called the PASE Station, became the sixth-tallest structure in San Francisco, there was speculation that Shoale would go bankrupt, but instead he expanded the operation by building the Wellness Center, a four-acre campus in Daly City where people could study PASE intensively. Then he started the PASE Process, a charitable organization that infused money and crackerjack administrative staffs into underfunded soup kitchens, homeless shelters, and daycare centers in low-income areas of the city. It also gave grants to arts companies, medical research labs, and neighborhood development centers. At some point within the last couple of years a small but high-profile group of celebrities had begun talking in interviews about their conversion to PASE, and it had made international headlines the previous spring when the French government objected to its building a Wellness Center in Marseilles. That surprised me because I’d thought PASE was strictly a California phenomenon.

In general, though, I didn’t think about it. The West Coast gives birth to several religions annually, and although PASE had lasted longer and was better financed and more diversified than most, like them it seemed destined to struggle for a place on the country’s spiritual landscape before fading into the same horizon that had swallowed New Thought, the I AM movement, and hundreds of indigenous American faiths before it. If anything, it was at a disadvantage to the others because it condemned sex in every form; I couldn’t imagine it attracting more than a few thousand followers at any one time. Yes, PASE looked likely to burn through a dry distant swath of the population without threatening the green habitable land in which I lived.

Max and I pulled into a thirty-story parking garage at the Station and found a space sliced thin by two flanking armor-plated vans on the top floor. In the street-level lobby of the adjacent Citadel we joined our coworkers grazing on donuts and coffee, waiting for the seminar to begin. Max stopped to talk to someone and I went in search of the bathroom, along the way grabbing two maple bars and an apple strudel from the buffet table, which I ate crouched down in a stall. I returned to find Max with Dexter and Ravi at the orientation booth discussing the unemployment figures that had just been released and the crippling effect these would have on next quarter’s accounts retention.

“You guys seen Mr. Raven?” I asked.

Max pointed to a wall covered with pamphlets and book displays, beneath a giant video banner that said “Keep the PASE,” where Mr. Raven was talking to a member of the board of directors I’d only seen at weekend retreats and regional conferences. He was walking two fingers across his open palm as if to illustrate a story about someone running.

Deciding to wait for a more private moment to talk to him, I studied an orientation packet until the loudspeakers announced that the seminar was about to begin, whereupon we filed into a vast auditorium with sloped stadium seating that ringed an oval stage on which a thick wooden podium stood like a tree trunk. I sat between Max and Ravi and arranged my handheld devices on the pull-out desktop. Calibrated the personal light settings. Stretched and cracked my neck. Max ate a thick chocolate donut and held a cheese Danish in his lap.

“What?” he asked.

“Nothing,” I said.

“You could have gotten your own.”

“I’ve quit eating sweets as part of my post-surgery diet.”

On the stage down below a man in a dark brown suit approached the podium and clipped a microphone to his tie just below the knot. Tapping it twice, he said, “Good morning. My name is Denver Stevens, and I’m the PASE corporate activities director. I’d like to begin today’s events by saying that although they are open to men of all faiths and creeds, our approach will use techniques and ideas developed in Prescription for a Superior Existence. This powerful spiritual system, parts of which will become familiar to you today, can help liberate you from the dangers of overintimacy at the workplace.”

There was so much work to do on Danforth in so little time. Either my computer and email programs had randomly and momentarily malfunctioned or someone had sabotaged them. If the latter, who would do it and why? No one personally benefited if the report was late. Our computer system’s firewall was the best in the industry. I had no enemies.

When Denver Stevens stopped talking and left the stage to respectful applause, the lights dimmed and people shifted around in their seats. I began to feel panicky, as though stuck in traffic going to the airport, and I might have snuck back to the office if at that moment a spotlight hadn’t interrupted the darkness to shine on a man climbing the steps to the stage. Like a wax figure, Montgomery Shoale too perfectly resembled images of him I’d seen in the media: short and barrel-chested, wearing a perfectly tailored suit, with a relaxed executive presence. Around the base of his bald skull a two-inch band of white hair angled down into a trim Viennese beard.

“Hello,” he said in a soft baritone that through the room’s space-age acoustics sounded everywhere at once. “We’re delighted to have you with us today. When your chief executive operator, Mr. Hofbrau, called me to arrange this seminar, I was saddened but not surprised to hear about recent events at Couvade, and I assured him that our primary concern here is with helping people—with helping you—more fully appreciate what it means to have a personal and a professional self, and how to improve in each until perfection is inevitable. As the great Russian doctor and writer Anton Chekhov once observed, ‘Man will become better when you show him what he is like.’ We hope that after today’s activities you will know yourselves better and so be better.”

One of the other candidates for the senior manager promotion might have wanted to hurt my prospects in order to bolster his or her own, but I couldn’t think of any who had both the refined Machiavellian instincts and the technological skill to intercept my email and override my password file protection.

“I don’t know you all as individuals. Sitting beside a vegetarian might be a carnivore. Next to a pacifist, a war-supporter. There may be two men among you who claim nothing in common but an employer, and even that may be a bone of contention. As human beings, however—and more specifically as men—you are in many crucial ways the same. You eat and sleep and wear clothes. You use language to communicate. You feel joy and anger and love. You were born and you are going to die.” He took a sip of water. “From these common traits we can draw certain conclusions: eating reflects a common desire for food, sleep meets a desire for rest, and clothes answer a desire for warmth and propriety.” He paused and I looked for Mr. Raven in the audience. “We could spend a whole day—a whole lifetime, perhaps—talking about your desires and what is done to gratify them, but today we’re interested in one in particular: your desire for sex.”

I asked Max in a low voice if he would give me the Danish, and he said no.

“You might ask what is wrong with sex and point out that no one, with the exception of a few test-tube babies, would be here without it. You might say that it is a fundamental part of us. That would be understandable. At one time I myself would have said the same things, for I too once knew the full force and function of sexual desire, the urge that begins with the sight of a pair of legs or a bawdy joke or a warm object held in one’s lap, and grows until nothing matters but the satisfaction of that urge. And like many of you here today, I believed that I was fine.” Shoale took another sip of water. “But was that true? Are you fine? Your eyes, like mine were, are forever restless in their sockets; you covet your neighbors’ wives and sisters and daughters and mothers; you fidget from the time you wake up until you go to sleep, and even then the fidgeting doesn’t stop. You’re like live wires that can’t be grounded for more than a few hours at a time.” He let this sink in for a moment. “The majority of sexual attraction takes place in the mind, where you are, in a word, distracted. Deeply so. And what are the consequences of this distraction?” A few hands rose timidly in the air. “You contract costly, disfiguring, sometimes even deadly diseases; your marriages break up; your job performance suffers; you hurt others and subsidize prostitution and make false promises. You become dissatisfied with life and lose the respect of your friends, families, and coworkers. You don’t say hello to someone without figuring the odds of getting them into your useworn bed. You spend idle, obsessive hours poring over Internet pornography like prospectors burning with gold fever, and in the end a sad onanist looks out at you from the mirror.” Next to me, Max was breathing heavily. “This is a sickness as debilitating as tuberculosis or emphysema. You are aware of its symptoms, yet you don’t try to get well.”

My thoughts swung between Danforth and Shoale’s speech and my fatigue from not having had any replenishing sleep in three months. With a small cough Max stood up and stalked out to the aisle, ignoring the grunts of men whose knees he banged.

“Is he okay?” I whispered to Dexter, who’d sat on the other side of him.

Dexter shrugged.

Max ran up the aisle and out the door. I thought about going after him but spotted Mr. Raven seven rows down and twelve columns over, staring at me with eyes as dark and cold as two black moons, so I returned my focus to the stage and tried to concentrate on what was being said.

This opening speech made me wonder why our CEO thought the seminar would be helpful. Some of the incidents Shoale had alluded to at Couvade were serious—a vice-president was being sued by his secretary for telling her inappropriate jokes, an accounts manager had downloaded a virus-infected pornography file onto his work computer that immobilized our entire system for two days, a field representative had been arrested for buying a child bride in Indonesia, and of course there was my squad’s own ill-executed trip to Chicago—but such a stridently antisex message seemed farcical and doomed to fail with the men of Couvade, whom I’d seen at bachelor parties and after-work clubs and company retreats to Florida.

The rest of the day’s content, however, was more effective. After Shoale’s talk we watched a documentary about sex crimes and one about the ravages of sexually transmitted diseases that featured disturbing footage of a syphilitic man having his nose surgically removed. Then we had lunch and came back to form small discussion groups and role-play exercises—when alone with someone we found attractive, we were to talk only about work-related subjects, even if that person tried to make things personal—before concluding the day with a lecture from Shoale that took a more positive, empowering tone than his first: “You have the ability to be as great as anyone who ever walked the Earth,” he said. “Gandhi, Buddha, and even Jesus suffered the same temptations and trembled from the same desires that you do. What made them different—what can make you different—is that they heeded the call of their best selves. They made the choice, as you can, to rise above the squalor of desire.”

Several men around me nodded thoughtfully while gathering together their things.

From there I raced back to the office and finished Danforth at four A.M. Then I went home, slept for three hours, and by nine the next morning was seated at my cubicle, where I opened an email from Mr. Raven. I felt a burning sensation in my right wrist and popped two homeopathic pills that went on to have no effect.

“Mr. Raven?” I knocked lightly on his door.

“Come in,” he said, pushing aside his keyboard. Commemorative posters of marathons and charity races covered the wall space not taken up with shelves of corporate histories, mambo primers, and presidential biographies. Through the window I could see latticed scaffolding in front of a former hotel being converted to office space. Mr. Raven patted his gelled gray hair, which lay frozen across his scalp like a winter stream.

“Sit down,” he said, moving things around on his desk—a box of chocolate mints, a pair of Mongolian relaxation balls, a penknife—and fingering a reddish birthmark on his chin. “I assume you know why I want to see you.”

“Is it about Danforth Ltd.?”

Mr. Raven appreciated candor about painful or difficult subjects, as well as when bold action was required. We’d discussed Harry Truman once and, while acknowledging and finding fault with his faults, we’d approvingly measured the strength of his character—its unflinching directness—because of which he could say without hypocrisy that the buck stopped with him. A true leader saw, identified, and accepted mistakes while learning how not to repeat them.

“Please tell me why it was late.”

“I first sent it to you on Tuesday and didn’t know that you hadn’t received it until yesterday morning. I would have done it again right away except that the sensitivity training seminar was about to start.”

“Which your actions largely occasioned.”

“That’s—”

A questioning look settled on Mr. Raven’s face.

I drew my left ankle up onto my right knee and pulled at the pant leg material. “As you know, there were four of us in Chicago. I didn’t see the credit card Juan used and figured it was his personal one, and we’d pay him back later. This isn’t to say I’m blameless—the whole thing reflected bad judgment, including my own—but I’ve already had my wages garnished to make up my quarter of the expense account item, and I formally addressed the Employee Conduct Board last week and volunteered to do community service as well as—”

Mr. Raven leaned forward with a hard, penetrating look and said, “Let’s cut the folderol.”

“Excuse me?”

“We both know you’re a sick man.”

“Excuse me?”

“Your performance at Couvade has been greatly compromised lately, and you now have a choice. You can take a leave of absence and get healthy. Check into a sex addiction clinic like the PASE Wellness Center in Daly City. Work on this problem and beat it. Or you can accept the ten demerit points I’ll have to issue you for Danforth Ltd., which combined with your ten demerits from the Employee Conduct Board would total the twenty required for me to fire you.”

I swallowed thickly and felt the beginning of a sinus headache, of my tear ducts opening and throat constricting. Mr. Raven pushed a box of tissues toward me. I rose and then sat back down.

“The Board is giving us ten demerits?”

“You’ll get a copy of their written decision.”

“I don’t understand.”

Mr. Raven’s voice softened and his forehead relaxed, lowering his hair a quarter inch. “It’s going to be okay. You’ll undergo treatment and then, following a probationary period of not less than eighteen months, I’ll review your case and consider your coming back to work for Couvade.”

“No, this is wrong. Danforth was a mysterious accident, and I’d like to appeal to the Conduct Board for a reduced penalty.”

“It’s too late for that.”

“You’re telling me this for the first time right now!”

Mr. Raven, still holding the base of the tissue box, pulled it away from me and then picked up his phone. “Don’t make me call security.”

“But I’m being railroaded. You can’t—What if you call the system administration department and ask them to recover my Tuesday computer profile and they’ll tell you that I’m not lying about Danforth? In a situation this serious, you have to!”

I quit yelling and Mr. Raven set down his phone and we stared at a midway point between us for the seventy-three seconds it took two building security officers to arrive and lift me to my feet. I weighed a thousand pounds in their arms.

CHAPTER 3 (#u61a501a2-f4f8-5fb3-9bde-cdd4706631e2)

Following my meeting with Ms. Anderson at the Wellness Center, the escorts took me to the dining hall, a high-ceilinged oval room with rectangular metal tables, where, arriving as the others were finishing, I ate a four-egg omelet with sausage links and home fries. Nothing tasted as good as it looked, being made of the sort of low-fat, low-cholesterol ingredients that I’d bought after my surgery and then never again, but I took comfort in the act of eating and didn’t get up from the table until my escorts said that the orientation meeting was about to start in the Celestial Commons building. I would have argued that I didn’t care about missing the beginning—or the middle or the end—if I thought they’d care that I didn’t care; instead I followed them out.

Having felt like an animal caught in a steel trap during my conversation with Ms. Anderson—when I discovered that I lacked the strength to chew off my own foot—just then I felt calm and self-possessed. I walked steadily between my escorts. This was all temporary. Conrad must have understood PASE’s role in my being shot and taken away, meaning either the police or FBI would arrive at any minute to rescue me from this horrible compound. It was important that I not panic, that I keep my wits and be ready to level sane and convincing charges against my captors. A cigarette would have helped, or a stick of nicotine gum, or an assortment of pills with something liquid to chase them, but I made tight fists and clenched my jaw and knew that this was about to be over. Back in the courtyard I looked for signs of disturbance, not knowing if the authorities would drop from a helicopter in a SWAT team raid or storm the front gate, or if their warrant and tact would help them avoid an open and violent confrontation with the Center’s security guards. Everything was quiet. The escorts looked straight ahead, one in front and the other behind me. As a giant clock tower struck eight A.M., I tried not to think of what was delaying my rescuers.

The orientation meeting, in a room on the first floor of the Celestial Commons building, was led by Mr. and Mrs. Rubin—a small, round couple with nearly identical bodies, like two pieces in a Russian doll sequence, Mrs. Rubin could have nested snugly inside her husband—who handed me a notebook and a small bottled water and introduced me to the four other new arrivals at the Wellness Center: Rema, a tax assessor from Seattle; Shang-lee, a chemical engineering graduate student at Stanford; Alice, an obstetrician from Alameda; and Star, a retired “friend to gentlemen” from Key West. I sat in the chair closest to the door and waited for the door behind me to open and my release to be effected.

Mrs. Rubin rolled up her tunic sleeves and stepped forward. “Does anyone have a question before we begin?”

“No,” answered Mr. Rubin immediately. “Okay, first of all, congratulations on taking the first, most difficult step toward improving. The worst is already behind you. From now on, each successive step will be easier than the last until, near the end, your feet will hardly touch the ground as you bound toward the perfection of UR God. But I must warn you that this won’t come at the same time for everyone. Just because you’re here in orientation together does not mean you will progress with identical speed. Some Pasers advance quickly and others slowly, which is okay because we are not in a race. UR God will be as ready for you in fifty years as in fifty days.”

A short but purposeful knock came at the door. Mr. and Mrs. Rubin looked at each other quizzically and then moved in concert toward it. Trembling with relief, I envisioned the squad of armed men about to enter, call my name or even recognize my face, and lead me back to my apartment, where I could expect the law’s full protection until my safety was established. Which wouldn’t take long. Once PASE’s criminal intentions toward me were proven beyond question—a day? two days?—my only concern would be how much to ask for in damages. As far as I knew, Shoale’s private fortune had been blended into PASE’s coffers, meaning I might expect millions—perhaps tens of millions—of dollars, depending on how sympathetic a jury I got. Couvade would probably offer me a vice-presidency or some equally nice sinecure to restore its mainstream image and distance itself from the PASE fallout. Women from all over the Bay Area and beyond would read about me and, their interest piqued in someone who had almost been murdered before being forced into a celibacy camp and then awarded an enormous compensation settlement, seek me out. Yes, for several seconds in that orientation room, at the end of a row of desperately gullible people from whose rank I was about to escape, I foresaw a hasty and lucrative resolution to all of my problems. Part of me even dared to imagine Mary Shoale, whom I loved more with every passing second, seizing the moment to break from her father and make me the happiest of men. What had been my terrible luck was going to be flipped around and turned right side up.

Except that it wasn’t. Mr. and Mrs. Rubin cautiously opened the door, consulted in whispers with a young man and woman in regulation tunics, and then returned to the center of the room, smiling as though they had swallowed a bottle of Percodan.

“Sorry for the interruption,” Mr. Rubin said, “but we’ve just received wonderful news. Tonight, following Synergy, Montgomery Shoale will make a major announcement via a live video address that we’ll watch at the Prescription Palace. You are new here and so can’t appreciate how rare and magnificent an event this is, but to give you some perspective I’ll say that it’s been many months since Mr. Shoale last spoke to us.”

“Five months,” said Mrs. Rubin gently, though with a correcting tone.

“He is close to becoming an ur-savant, and this could be his last public appearance. You will witness history in the making.”

Shang-lee, whose unlined face and glinting gray hairs placed him between twenty and fifty, and who, besides me, was the only one not reflecting the Rubins’ smile, adjusted his small round spectacles, raised a bony hand, and said, “What’s an ur-savant?”

“You will learn about the savant stages later today in class,” said Mrs. Rubin. “Our purpose now is to provide you with background on the Wellness Center, its history and aims and rules of conduct, so that you’ll know what to expect and how to behave while here.”

During the ensuing account, told in alternating sections by the Rubins, I fought against the fear that every passing minute made my rescue less likely, that if the police weren’t there yet it was because Conrad hadn’t told them. Or they disbelieved him. Or they were in league with PASE and, even given proof that I was being held against my will, not going to help me. I closed my eyes and willed the door to open, an amateur’s telekinesis. At nine A.M.—twelve hours since I’d been shot and kidnapped—full of disappointment and desire for pills and alcohol and tobacco, I wiped away two tears caught in my eyelashes and fought down a rumbling nausea.

Mr. and Mrs. Rubin explained that this Wellness Center, a mere three miles from the San Francisco PASE Station, had been built eight years earlier based on a blueprint drawn up by Montgomery Shoale and provided through revelation by UR God. The first of its kind, it provided the model for the other Wellness Centers subsequently established in Los Angeles, Houston, Chicago, and New York, as well as for those planned in or near Buenos Aires, São Paulo, Edinburgh, Cornwall, Tangiers, Marseilles, Utrecht, Riga, Seoul, and Sidney. Mrs. Rubin punched something into a laptop computer and a montage of photos blanketed the wall behind her showing the various stages of each new Center’s completion. Like the Daly City original, they were all set on four acres and would, when completed, have an outdoor park with a botanical garden, a meditation post, two residential dormitories (one for men and one for women), an education building (Celestial Commons), a screening facility (Prescription Palace), a hospital (Freedom Place), a library and administration building (Shoale Hall), a recreation building, a dining hall, and a church (Synergy Station). They would all house forty guests at a time, an even number of men and women, whose activities would be fully integrated.

Although the architecture varied slightly from one Center to another, as did the flowers in the botanical garden and the food served in the dining halls to reflect local produce and culinary traditions, life would follow a set schedule at all of them: 6 A.M. wake up. 6:30 A.M. exercises. 7:15 A.M. breakfast. 8 A.M. reading/studying. 10 A.M. counseling. 12 P.M. lunch. 1 P.M. class. 3:30 P.M. individual research. 4:30 P.M. recreation. 6 P.M. dinner. 7:30 P.M. all-guest activity. 10 P.M. lights-out. On Sundays there was a thirty-minute Synergy session at 7 P.M.

And what exactly was the purpose of a Wellness Center? What did Montgomery Shoale hope it would accomplish? Although in practice its functions and benefits were too many to count, it was designed to speed along neophytes’ and longtime Pasers’ journey toward permanent synergy with UR God, the fusion of everyone into His vast being and thus the end of human strife on Earth. Shoale’s goal was our own. He personally interviewed all the doctors and staff, who then underwent a rigorous training program and six-month probation period before being brought to work at a Center full-time. He kept in close contact with all the individual directors and monitored the progress of their operations worldwide.

In addition to treating the normal range of behaviors that had to be modified and/or eliminated—sexuality, rage, material greed, television, Internet abuse, etc.—the Center was equipped to help people with problems involving addiction, extreme emotional imbalance, and psychiatric disorders. According to its strictly refined physical and spiritual practices, it helped these unfortunate guests using a holistic approach to mind and body and soul wellness taken from The Prescription, which, in its wisdom, recognized that while everyone needed to improve, some were, at the time they reached adolescence or adulthood, at such a deficit that they required extreme and immediate preimprovement treatment. For example, the Center’s hospital included a Seclusion Ward that provided twenty-four-hour care for sufferers from drug withdrawal, during which the guests’ isolation was leavened by audio recordings of Montgomery Shoale lectures, as well as by frequent use of a Synergy device and special stretching techniques favored by UR God and interpreted by Mr. Shoale. PASE enjoyed a hundred percent success rate in curing heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine addiction, as it did with freeing guests of anger, violent tendencies, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, generalized anxiety, misanthropy, boredom, acute narcissism, and—

“What are you doing, Mr. Smith?” Mr. Rubin asked, cutting off his wife’s speech.

I’d gotten up from my seat and walked to a window overlooking the courtyard. “Just checking something.” As when I’d crossed it earlier, there were no policemen or FBI agents visible, though I told myself that they could be talking to Ms. Anderson or some other administration figure, trying to ascertain where I was being kept, on the verge of taking the noncooperative Pasers into custody and beginning an exhaustive hunt around the premises for me. I looked for a latch or lever with which to open the window—thinking I would scream out for help and catch the attention of either the law or someone passing by on the other side of the Center wall—but it was sealed shut.

I heard Mr. Rubin take a few steps toward me and then stop. “During instructional sessions like this one, there is a basic protocol for being excused from your seat to go to the bathroom or attend to another Center-approved activity. Please sit back down and I’ll explain it to you.”

“I’d rather stand here, if you don’t mind.”

Mrs. Rubin said, “We do. We mind very much.”

A door opened in the building across the courtyard and two men emerged, one of whom wasn’t wearing a blue tunic. I tried to make out whether he had a metallic badge on his breast or walked as officiously as someone in the intelligence community, but at that distance I couldn’t tell.

“We really must insist,” said Mr. Rubin. “Please don’t make this difficult for us and yourself.”

The two men walked in my direction and disappeared under the foliage of a pair of eucalyptus trees shooting up like twin geysers in the middle of the courtyard.

“Go on with what you were saying,” I said, waiting for the non-tunic man to come back into view, when he would be close enough for me to make out his clothing and features. But then four meaty hands gripped my arms, turned me around, and roughly pulled me back to my seat. My escorts withdrew from the room after nodding tersely to Mrs. Rubin, who bit her lower lip and looked at me pityingly.

I stared with dull hatred at the Rubins, who said that they would now go over the basic rules of conduct so that such disciplinary measures wouldn’t be necessary again. Anarchy did not reign at the PASE Wellness Center. Some actions were forbidden and others encouraged. In the first category, we were not allowed to leave the Center or receive visitors without permission. Television, books, and the Internet were okay with some built-in restrictions, for which reason certain programs and periodicals and websites were blocked or made inaccessible. We could not drink alcohol, take non-prescribed drugs, or engage in any sexual activity, including with ourselves. Profanity was prohibited, as was licentious talk and any attempt to leave the Center grounds before the facilitators deemed it appropriate. Disputes between guests were to be taken to a facilitator and should not involve violence or violent intent.

I thought I heard footsteps in the hall outside but it was just my teeth grinding.

Mr. and Mrs. Rubin knew that these restrictions sounded harsh. No one liked to be told they couldn’t do something. But Montgomery Shoale had devised them for our health and safety; otherwise our improvement would be no more possible than rain without clouds. Much was asked of guests at the Center, and in return much was given. We were worthy, infinitely capable people, for we came from UR God and would be with Him again someday. We had to bear in mind that reaching this destination was the most difficult, rewarding journey we would ever undertake.

“Did you say there’s going to be Synergy tonight?” I asked.

“Yes,” said Mr. Rubin.

“What is Synergy?” asked Shang-lee.

“So today is Sunday?”

“Synergy,” said Mrs. Rubin, while smoothing out a kerchief she’d held bunched in her left hand, “is the feeling of being fused into UR God.”

Mr. Rubin added, “It can be had on this planet in one of two ways. The first is with a Synergy device, which is like a big gyroscope that you stand in with electrodes connected to your temples. Synergy is, you’ll find, the most wonderful feeling imaginable, and when you become an ur-savant it is the only one you will ever experience again.”

“Sunday the nineteenth?” I said.

Mr. Rubin nodded and I leaned over and tried to throw up. I had been shot on Friday the seventeenth, meaning I had been unconscious for an entire day, meaning any immediate attempt to rescue me from the Wellness Center would already have ended. There was no cavalry on the way, no quick response to my dilemma. And this whole situation was neither a joke nor a social experiment. A camera crew was not filming behind a fake wall, ready to ask me how it felt to believe that I’d been forced into a PASE indoctrination camp. There was no winking host or thoughtful documentarian orchestrating my deception in a cruel and elaborate prank, and I would not have the chance to talk about how similar it was to my childhood fear of being sent to an orphanage full of seemingly well-intentioned people who were in fact bent on destroying my will. This was real.

Unable to vomit, I sat back and the orientation session ended. The Rubins thanked us for being good listeners and handed out information packets with a map of the Center grounds, a personalized schedule listing our counseling session and class locations, a rulebook, a pocket-sized edition of The Prescription for a Superior Existence, and a personal digital assistant with electronic copies of everything. The other guests, eyes on their packets, rose and filed out of the room, and Mrs. Rubin asked me civilly if I needed assistance in getting to my next event.

My itinerary said I was supposed to be in Room 227 of the Celestial Commons building, one floor above, so I left the room and paused to look up and down the hallway, where Shang-lee’s back was receding toward an Exit sign that marked the stairwell and elevator. Single escorts were placed at fifty-foot intervals between us, as motionless and erect as suits of armor. I passed these hollow men in their blue tunics, reached the stairs, and climbed them deliberately, going over problems that configured themselves in my head as a tetrahedron, with my separation from Mary on one side, my present incarceration on a second, my forced sobriety on a third, and my unemployment—with its implications for my debts—on a fourth. The first and fourth sides existed in the outside world, to which I didn’t have access presently, while the second and third affected me then and there, and had to be overcome. Which I didn’t know how to do. Shang-lee, Rema, Alice, and Star were out of sight when I got to the second-floor landing, apparently already in their counseling rooms.